Divine Judgment in the Book of Revelation James E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Last Plagues Lesson #11 for March 16, 2019 Scriptures: Revelation 15:1,4; 7:1-3; 14:9-10; 16:1-12,16; 17:1; Daniel 5; 2 Thessalonians 2:9-12

The Book of Revelation The Seven Last Plagues Lesson #11 for March 16, 2019 Scriptures: Revelation 15:1,4; 7:1-3; 14:9-10; 16:1-12,16; 17:1; Daniel 5; 2 Thessalonians 2:9-12. 1. Revelation 15 and especially 16 describe what are known as the seven last plagues. However, Revelation 15:2-4 talk about a group of people standing on the sea of glass in heaven, praising and honoring God. How is that related? Did John change the subject? 2. Revelation 15:5-8 set up the heavenly context for the giving of the seven last plagues. It is important to notice that no one is in the temple in heaven when these plagues fall. Normally, the throne room in heaven is full of millions of heavenly beings. This means that the events connected to the seven last plagues will take place after the close of probation. 3. But, the most important question to ask about the seven last plagues is who is the one that causes those seven last plagues? And what is the purpose of having seven final plagues if probation is closed and if no one will change his/her mind? An important verse to look at in connection with the seven last plagues is Revelation 11:18. It talks about a time of judgment when those who destroy the earth will be destroyed. 4. The group of people described in Revelation 15:1-4 will be victorious “over the beast, over his image and over his mark and over the number of his name.” (NKJV*) So, these people certainly cannot be those who are the main brunt of the seven last plagues. -

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

Revelation 18: the Fall of Babylon

Revelation 18: The Fall of Babylon Chapter 17 provided a chain of metaphors that identified Babylon. In chapter 17, verse 18, the woman on the beast is the great city, and in verse 5, she is Babylon the great. Leading up to chapter 18, in Revelation 14:8, where the three angels announce the coming wrath of God, John saw the second angel who said: 8 And another, a second angel, followed, saying, “Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great, that has made all the nations to drink of the wine of the wrath of her fornication.” As the wrath of God, in the seventh bowl, poured out in Revelation 16:19, John wrote, 19 And the great city was divided into three parts, and the cities of the nations fell: and Babylon the great was remembered in the sight of God, to give unto her the cup of the wine of the fierceness of his wrath. Chapter 18 goes into a great and detailed lament over the end of Babylon, the great city, where it contrasts with chapter 21 where the glories and beauties of the New Jerusalem—the bride of Christ, the heavenly city, the church—shines with the glory of God. Babylon with its citizens of the world versus the New Jerusalem with its saints, made perfect, tell the story of the redeemed and lost in these final chapters of God’s revelation. After chapter 18, the terms Babylon and great city do not appear again in The Revelation. Their retribution in this chapter is the very end of them. -

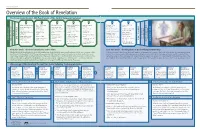

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Where Did They Come From? Revelation 7:9-17 a Sermon Preached in Page Auditorium on April 17, 2016 by the Rev

Where Did They Come From? Revelation 7:9-17 A Sermon preached in Page Auditorium on April 17, 2016 by the Rev. Dr. Luke A. Powery Each week we pray, “on earth as it is in heaven” because our present doesn’t yet match God’s promise so we keep striving, praying, moving, pressing, working, going to church, attending bible studies, singing hymns, giving alms, serving in the community, and taking communion. These are some signs that we desire “on earth as it is in heaven.” We want God’s future now, God’s future present. So many have yearned and dreamed for this moment that there are all kinds of end of the world predictions throughout history. Well before the end time imaginary predictions of the Left Behind book series, or the visions of Harold Camping (may he rest in peace), there was the year 1806. In that year, a domesticated hen in Leeds, England, appeared to lay eggs inscribed with the message “Christ is coming.” Great numbers of people reportedly went to see this hen and began to despair of the coming Judgment Day. It was soon discovered, however, that the eggs were not in fact prophetic messages of the future but the work of their owner, who had been writing on the eggs in ink and reinserting them into the poor hen’s body. If it was the end of anything, it was the end of that poor hen! But well before hens or Harolds, well before any of these, there is the revelation of John, literally the ‘apocalypse’ of John. -

THE DESTRUCTION of RELIGIOUS BABYLON Revelation 17

THE DESTRUCTION OF RELIGIOUS BABYLON Revelation 17 Revelation chapters 17 and 18 are an interlude in the sequence of Tribulation events. These chapters deal with the destruction of religious and economic Babylon. Dr. Charles Ryrie explains why Babylon is the figure used to describe these forces in the last days. Babylon has had a long and consistently dishonorable history. It had its beginnings around 3000 B.C. under Nimrod (Gen. 10:8–10). The tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1–9) was built to prevent people from scattering throughout the earth, in direct defiance of God's command to do so. Hammurabi made Babylon a religious power about 1600 B.C. by making Marduk god of the city of Babylon and head of a pantheon of 1,300 deities. Extra-biblical sources indicate that the wife of Nimrod became the head of the Babylonian mysteries, which consisted of religious rites that were part of the worship of idols in Babylon. Her name was Semiramis, and she supposedly gave birth to a son, Tammuz, who claimed to be a savior and the fulfillment of the promise given to Eve in Genesis 3:15. This anti-God Babylonian religion is alluded to in Ezekiel 8:14…, Ezekiel 8:14 (ESV) 14 Then he brought me to the entrance of the north gate of the house of the LORD, and behold, there sat women weeping for Tammuz. Jeremiah 7:18…, Jeremiah 7:17–18 (ESV) 17 Do you not see what they are doing in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? 18 The children gather wood, the fathers kindle fire, and the women knead dough, to make cakes for the queen of heaven. -

The Chronology of Revelation 19—20

Session #5 The Chronology of Revelation 19—20 The Expositors Seminary Super Seminar—April 8–9, 2016 I. Introduction § Key Question: Do the events of Rev 20:1–6 follow the events of Rev 19:11–21? OR Does Rev 20 take the reader back to the beginning of the NT era so that verses 1–6 describe the present age? Comparison of Views Ø The Sequential View of Premillennialism The Millennium of Rev 20 ____________ the Second Coming of Rev 19 Ø The Recapitulation View of Amillennialism The Millennium of Rev 20 ____________ the Second Coming of Rev 19 II. The Sequential View of Premillennialism A. The Introductory “And I Saw” (Rev 20:1) § Used _______ in Book of Revelation § Almost always introduces _______________ ________________ § Argument is _______________ but places burden of proof on amillennial view B. The Content of the Visions (Rev 20:1–6) § The binding of Satan is ____________ (not present) § The first resurrection is ____________ (not spiritual) § The thousand years is ____________ (not symbolic) Ø Therefore: The chronology of Rev 19-20 must be ________________! 19 C. The Use of “Any Longer” (Rev 20:3) § Rev 12–19 repeatedly highlights the satanic deception of the nations in the second half of the Tribulation (12:9; 13:14; 16:14; 18:23; 19:19–20). § Satan is then locked in the abyss “so that he would not deceive the nations any longer” (Rev 20:3), which indicates the interruption of a deception that was already taking place. § This connection indicates a historical progression in which the binding of Rev 20 is designed to halt the deception described in Rev 12–19. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

Babylon the Great Is Fallen, Is Fallen Revelation 18 Revelation 18 Introduction

Babylon the Great Is Fallen, Is Fallen Revelation 18 Revelation 18 Introduction • Today’s chapter deals with the destruction of the great city Babylon. • It brings together numerous prophecies from the Old Testament that have only been partially fulfilled. • The encouragement for God’s people is that they should all leave the city before its inevitable destruction. • The ruins of the city of ancient Babylon still exist in Iraq and were partially rebuilt by Saddam Hussein. • • Though Babylon is no longer great, the prophecies pertaining to its destruction have never been completely fulfilled. • We may therefore look forward to a further rebuilding of the city somewhere near its ancient location. • It seems that it will become Antichrist’s political and financial capital – the capital of the world. • Let’s look at some of the Old Testament prophecies. – Isaiah 13:19-22 – Isaiah 14:22-23 – Isaiah 47 – Jeremiah 50:35-40 – Jeremiah 51:6-9, 13, 17-19, 24-26, 29, 41-45, and 59-64 • Now we’ll read Revelation 18 in sections to help digest the full weight of the message. • Pay attention to the different voices that speak. • An Angel Announces Judgment 18:1-3 – The nations and kings have become corrupted. – The merchants of the earth have become rich. • A Voice from Heaven Calls for God’s People to Separate Themselves from Her 18:4-8 – We’ll consider what this separation means for us at the end our study. • The Voices of Those Who Mourn 18:9-19 – The kings of the earth 9-10 – The merchants of the earth 11-17a • 18:13 “Bodies and souls of men” points to human trafficking as part of the economy. -

18-Revelation Handouts

ENDGAME A Study On Revelation (Week #18) Pastor Jason Goss THYATIRA: PERSONAL APPLICATION Ephesus: Promise of ______________ (vs. Love Grown Cold) Smyrna: Promise of ______________ (vs. Physical Death) Pergamos: Promise of ______________ (vs. Social Compromise) THYATIRA: The Promise Of ______________ (vs. Avoiding ______________) Revelation 2:18 “And to the angel of the church in Thyatira write: The Son of God, who has eyes like a flame of fire, and His feet are like burnished bronze, says this: 19 ‘I know your deeds, and your love and faith and service and perseverance, and that your deeds of late are greater than at first. 20 But I have this against you, that you tolerate the woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophetess, and she teaches and leads My bond-servants astray so that they commit acts of immorality and eat things sacrificed to idols. 21 I gave her time to repent, and she does not want to repent of her immorality. 22 Behold, I will throw her on a bed of sickness, and those who commit adultery with her into great tribulation, unless they repent of her deeds. 23 And I will kill her children with pestilence, and all the churches will know that I am He who searches the minds and hearts; and I will give to each one of you according to your deeds. 24 But I say to you, the rest who are in Thyatira, who do not hold this teaching, who have not known the deep things of Satan, as they call them—I place no other burden on you. -

Revelation Chapter 3 Copy

Endgame: Study Of Revelation ENDGAME A Study On Revelation (Week #20) Pastor Jason Goss SARDIS: PROPHETIC APPLICATION Prophetic Profile • Sardis represents the DENOMINATIONAL church • One “body”, MULTIPLE HEADS • Fading away of strong DOCTRINE The Reformation: A Review • As early as the 13th century the papacy becomes vulnerable to attack - Greed, immorality, and ignorance of its officials in all ranks - These issues are what start the reformation - Vast tax-free possessions, as much as 1/5 to 1/3 of Europe - Incited the envy and resentment of the land-poor peasantry 14th Century • English reformer John WYCLIFFE boldly attacked the papacy striking at: - The sale of indulgences - The excessive veneration of saints - The moral and intellectual standards of ordained priests • To reach the common people - He translated the Bible into English rather than Latin - Convinced that every man, woman, and child had the right to read God’s Word in their own language • In 1382 he completed the first English translation of the Bible - The printing press had not yet been invented - It took 10 months for one person to copy a single Bible by hand • Wycliffe recruited a group of men that shared his passion for spreading God’s Word, and they became known as "Lollards." - Lollards worldly possessions behind setting out across England dressed in only basic clothing, a staff in one hand, and armed with an English Bible - They went forth to preach and win England for Christ! • The CHURCH CLERGY set out to destroy the itinerant preachers - Passing laws against their -

The Background and Meaning of the Image of the Beast in Rev. 13:14, 15

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2016 The Background and Meaning of the Image of the Beast in Rev. 13:14, 15 Rebekah Yi Liu [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Rebekah Yi, "The Background and Meaning of the Image of the Beast in Rev. 13:14, 15" (2016). Dissertations. 1602. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1602 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT THE BACKGROUNDS AND MEANING OF THE IMAGE OF THE BEAST IN REV 13:14, 15 by Rebekah Yi Liu Adviser: Dr. Jon Paulien ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STDUENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE BACKGROUNDS AND MEANING OF THE IMAGE OF THE BEAST IN REV 13:14, 15 Name of researcher: Rebekah Yi Liu Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jon Paulien, Ph.D. Date Completed: May 2016 Problem This dissertation investigates the first century Greco-Roman cultural backgrounds and the literary context of the motif of the image of the beast in Rev 13:14, 15, in order to answer the problem of the author’s intended meaning of the image of the beast to his first century Greco-Roman readers. Method There are six steps necessary to accomplish the task of this dissertation.