Eschatology, Liturgy, and Christology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dignitatis Humanae: the Catholic Church's Path to Political Security

Mystērion: The Theology Journal of Boston College Volume I Issue I Article 4 Dignitatis humanae: The Catholic Church’s Path to Political Security Sean O’Neil Boston College, [email protected] DIGNITATIS HUMANAE: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH’S PATH TO POLITICAL SECURITY SEAN O’NEIL1* Abstract: The Catholic Church has always had a complicated relationship with the political states in which it operates. While much of the Church’s history has shown that the institutional Church’s power relative to the state fluctuates as it has sought to retain political autonomy, it was in the centuries after the Enlightenment in which the most serious threats to the Church’s temporal security began to arise. Considering these alarming trends, the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on Religious Freedom (Dignitatis humanae) revisited the Church’s relationship with the state in an attempt to secure the Church’s political security in the twentieth century and beyond. Primarily focused on the right to religious freedom, Dignitatis humanae’s authors construct an argument based upon individual claims to religious liberty that ultimately allows the Church to confer upon itself similar protections. Though Dignitatis humanae cedes political authority, it reasserts the Church’s primacy in religious considerations, as well as the disparate judgmental capacities of religious and secular authorities. In concluding, this article will argue that Dignitatis humanae’s significance is two-fold: (1) the Church relinquishes claims to secular governing authority, but (2) elevates its true source of political protection—its individual members—to the forefront of its concern. Introduction In response to questioning from the council of Hebrew elders about his preaching of the Gospel, Saint Peter noted: “We must obey God rather than any human authority. -

The Significance of Lesslie Newbigin for Mission in a New Millennium

The Significance of Lesslie Newbigin for Mission in the New Millennium Michael W. Goheen A Remarkable Life Bishop Lesslie Newbigin is one of the most important missiological and theological thinkers of the twentieth century. The American church historian Geoffrey Wainwright, from Duke University, once remarked that when the history of the church in the twentieth century comes to be written, if the church historians know their job, Newbigin will have to be considered one of top ten or twelve theological figures of the century. In his book, he honours Newbigin’s significant contribution by portraying him in patristic terms as a “father of the church.”1 Newbigin was first and foremost a missionary; he spent forty years of his life in India. But he was much more: he was a theologian, biblical scholar, apologist, ecumenical leader, author, and missiologist. The breadth and depth of his experience and his contribution to the ecumenical and missionary history of the church in the twentieth century have been “scarcely paralleled.”2 Newbigin was born in England in 1909. He was converted to Jesus Christ during his university days at Cambridge. He was married, ordained in the Church of Scotland, and set sail for India as a missionary in 1936. He spent the next eleven years as a district missionary in Kanchipuram. He played an important role in clearing a theological impasse that led to the formation of the Church of South India (CSI)—a church made up of Congregationalists, Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Methodists. He served as bishop of Madurai for the next twelve years. -

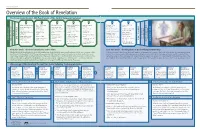

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Objectivity, Values, and the Christian Librarian

Volume 44 | Issue 2 Article 4 2001 Objectivity, Values, And The hrC istian Librarian Steve Baker Union University The Christian Librarian is the official publication of the Association of Christian Librarians (ACL). To learn more about ACL and its products and services please visit //www.acl.org/ Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/tcl Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Steve (2001) "Objectivity, Values, And The hrC istian Librarian," The Christian Librarian: Vol. 44 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/tcl/vol44/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Christian Librarian by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OBJECTIVITY, VALUES, AND THE S LIB Steve Baker, e central questions of Christian basis of our work, but sooner or later librarianship in the postmodern we run headlong into circumstances that Emma Waters world involve the philosophical force us to examine the nature and implica Summer Library, grounds of collection development. Are tions of our professional value system. there reliable objective grounds for Recently, one of our more thought Union University, attempting to build balanced collections? ful students came to me with several Jackson, Tennessee What values ought to guide the librarian in books on Catholicism that she wanted this task? How will the application of those to donate to the library. She indicated values differ in the context of an evangelical her dissatisfaction with the quality of Christian institution? the collection with regard to Catholic It is no secret that librarianship is Church teaching. -

Spe Salvi: Assessing the Aerodynamic Soundness of Our Civilizational Flying Machine

Journal of Religion and Business Ethics Volume 1 Article 3 January 2010 Spe Salvi: Assessing the Aerodynamic Soundness of Our Civilizational Flying Machine Jim Wishloff University of Lethbridge, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jrbe Recommended Citation Wishloff, Jim (2010) "Spe Salvi: Assessing the Aerodynamic Soundness of Our Civilizational Flying Machine," Journal of Religion and Business Ethics: Vol. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jrbe/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the LAS Proceedings, Projects and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion and Business Ethics by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wishloff: Spe Salvi INTRODUCTION In his very popular book Ishmael, author Daniel Quinn questions the sustainability of our civilization in a thought-provoking way. Quinn does this by asking the reader to consider the early attempts to achieve powered flight, and, more specifically, to imagine someone jumping off in “one of those wonderful pedal-driven contraptions with flapping wings.”1 At first, all seems well for the would-be flyer but, of course, in time he crashes. This is his inevitable fate since the laws of aerodynamics have not been observed. Quinn uses this picture to get us to assess whether or not we have built “a civilization that flies.”2 The symptoms of environmental distress are evident, so much so that U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon puts us on a path to “oblivion.”3 Add to this the economic and cultural instability in the world and it is hard not to acknowledge that the ground is rushing up at us. -

Building Your Library Strategically

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Jerry Falwell Library 2003 Building Your Library Strategically Gregory A. Smith Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lib_fac_pubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Gregory A., "Building Your Library Strategically" (2003). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 67. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lib_fac_pubs/67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Falwell Library at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liberty University From the SelectedWorks of Gregory A. Smith April 2003 Building Your Library Strategically Contact Start Your Own Notify Me Author SelectedWorks of New Work Available at: http://works.bepress.com/gregory_smith/25 Building Your Library Strategically* Gregory A. Smith One of my responsibilities as Library Director at Baptist Bible College is overseeing the development of our library’s collection. Over the last seven years we’ve spent more than $350,000 on books, periodicals, on-line databases, and other media. Needless to say, I’ve learned a lot about selecting library resources during this time. Of course, building one’s private library is different from developing a collection to support the research activities of hundreds of students and faculty. Nevertheless, I’ve found that many of the strategies I employ in building the Vick Library’s collection have served me well as I’ve expanded my personal library. Below I will share seven principles of library development that should enable readers to build effective collections while wasting minimal amounts of time, money, and shelf space. -

Pope Benedict XVI's Invitation Joseph Mele

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2008 Homiletics at the Threshold: Pope Benedict XVI's Invitation Joseph Mele Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mele, J. (2008). Homiletics at the Threshold: Pope Benedict XVI's Invitation (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/919 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOMILETICS AT THE THRESHOLD: POPE BENEDICT XVI‘S INVITATION A Dissertation Submitted to The McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Joseph M. Mele May 2008 Copyright by Joseph M. Mele 2008 HOMILETICS AT THE THRESHOLD: POPE BENEDICT XVI‘S INVITATION By Joseph M. Mele Approved Month Day, 2008 ____________________________ ____________________________ Name of Professor Name of Professor Professor of Professor of (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) ____________________________ ____________________________ Name of Professor Name of Professor Professor of Professor of (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ___________________________ ____________________________ Name of Dean Name of External Reviewer Dean, The McAnulty -

Examining Nostra Aetate After 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time / Edited by Anthony J

EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time Edited by Anthony J. Cernera SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2007 Copyright 2007 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Examining Nostra Aetate after 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in our time / edited by Anthony J. Cernera. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-888112-15-3 1. Judaism–Relations–Catholic Church. 2. Catholic Church– Relations–Judaism. 3. Vatican Council (2nd: 1962-1965). Declaratio de ecclesiae habitudine ad religiones non-Christianas. I. Cernera, Anthony J., 1950- BM535. E936 2007 261.2’6–dc22 2007026523 Contents Preface vii Nostra Aetate Revisited Edward Idris Cardinal Cassidy 1 The Teaching of the Second Vatican Council on Jews and Judaism Lawrence E. Frizzell 35 A Bridge to New Christian-Jewish Understanding: Nostra Aetate at 40 John T. Pawlikowski 57 Progress in Jewish-Christian Dialogue Mordecai Waxman 78 Landmarks and Landmines in Jewish-Christian Relations Judith Hershcopf Banki 95 Catholics and Jews: Twenty Centuries and Counting Eugene Fisher 106 The Center for Christian-Jewish Understanding of Sacred Heart University: -

First Theology Requirement

FIRST THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT THEO 10001, 20001 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY: BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL **GENERAL DESCRIPTION** This course, prerequisite to all other courses in Theology, offers a critical study of the Bible and the early Catholic traditions. Following an introduction to the Old and New Testament, students follow major post biblical developments in Christian life and worship (e.g. liturgy, theology, doctrine, asceticism), emphasizing the first five centuries. Several short papers, reading assignments and a final examination are required. THEO 20001/01 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL GIFFORD GROBIEN 11:00-12:15 TR THEO 20001/02 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 12:30-1:45 TR THEO 20001/03 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 1:55-2:45 MWF THEO 20001/04 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 9:35-10:25 MWF THEO 20001/05 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 4:30-5:45 MW THEO 20001/06 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 3:00-4:15 MW 1 SECOND THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT Prerequisite Three 3 credits of Theology (10001, 13183, 20001, or 20002) THEO 20103 ONE JESUS & HIS MANY PORTRAITS 9:30-10:45 TR JOHN MEIER XLIST CST 20103 This course explores the many different faith-portraits of Jesus painted by the various books of the New Testament, in other words, the many ways in which and the many emphases with which the story of Jesus is told by different New Testament authors. The class lectures will focus on the formulas of faith composed prior to Paul (A.D. 30-50), the story of Jesus underlying Paul's epistles (A.D. -

Beauty As a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2015 Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger John Jang University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jang, J. (2015). Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/112 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Philosophy and Theology Sydney Beauty as a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger Submitted by John Jang A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy Supervised by Dr. Renée Köhler-Ryan July 2015 © John Jang 2015 Table of Contents Abstract v Declaration of Authorship vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 Structure 3 Method 5 PART I - Metaphysical Beauty 7 1.1.1 The Integration of Philosophy and Theology 8 1.1.2 Ratzinger’s Response 11 1.2.1 Transcendental Participation 14 1.2.2 Transcendental Convertibility 18 1.2.3 Analogy of Being 25 PART II - Reason and Experience 28 2. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

The Cross and the Crucifix by Steve Ray

The Cross and the Crucifix by Steve Ray Dear Protestant Friend: You display a bare cross in your homes; we display the cross and the crucifix. What is the difference and why? The cross is an upright post with a crossbeam in the shape of a “T”. A crucifix is the same, but it has Christ’s body (corpus) attached to the cross. As an Evangelical Protestant I rejected the crucifix—Christ was no longer on the cross but had ascended to heaven. So why do I now tremble in love at the site of a crucifix? Let’s examine the history and issues surrounding the two. I will start with the Old Testament and the Jews’ use of images and prohibition of idols. I know in advance that it is not a thorough study, but it will give a general overview of the issues. I will try to provide a brief overview of the Cross and the Crucifix, the origin, the history, and the differing perspectives of Catholic and Protestant. It will try to catch the historical flow and include the pertinent points. The outline is as follows: 1. The Three Main Protestant Objections to the Crucifix 2. Images and Gods in the Old Testament 3. Images and Images of Christ in the New Testament 4. The Cross in the First Centuries 5. The Crucifix Enters the Picture 6. The “Reformation” and Iconoclasm 7. Modern Anti-Catholics and the Crucifix 8. Ecumenical Considerations The Three Main Protestant Objections to the Crucifix Let me begin by defining “Protestant” as used in this article.