THE LAST JUDGMENT in CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY Alison Morgan Public Lecture Given in the University of Cambridge, 1987

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

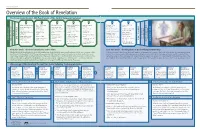

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Scheherazade

SCHEHERAZADE The MPC Literary Magazine Issue 9 Scheherazade Issue 9 Managing Editors Windsor Buzza Gunnar Cumming Readers Jeff Barnard, Michael Beck, Emilie Bufford, Claire Chandler, Angel Chenevert, Skylen Fail, Shay Golub, Robin Jepsen, Davis Mendez Faculty Advisor Henry Marchand Special Thanks Michele Brock Diane Boynton Keith Eubanks Michelle Morneau Lisa Ziska-Marchand i Submissions Scheherazade considers submissions of poetry, short fiction, creative nonfiction, novel excerpts, creative nonfiction book excerpts, graphic art, and photography from students of Monterey Peninsula College. To submit your own original creative work, please follow the instructions for uploading at: http://www.mpc.edu/scheherazade-submission There are no limitations on style or subject matter; bilingual submissions are welcome if the writer can provide equally accomplished work in both languages. Please do not include your name or page numbers in the work. The magazine is published in the spring semester annually; submissions are accepted year-round. Scheherazade is available in print form at the MPC library, area public libraries, Bookbuyers on Lighthouse Avenue in Monterey, The Friends of the Marina Library Community Bookstore on Reservation Road in Marina, and elsewhere. The magazine is also published online at mpc.edu/scheherazade ii Contents Issue 9 Spring 2019 Cover Art: Grandfather’s Walnut Tree, by Windsor Buzza Short Fiction Thank You Cards, by Cheryl Ku ................................................................... 1 The Bureau of Ungentlemanly Warfare, by Windsor Buzza ......... 18 Springtime in Ireland, by Rawan Elyas .................................................. 35 The Divine Wind of Midnight, by Clark Coleman .............................. 40 Westley, by Alivia Peters ............................................................................. 65 The Headmaster, by Windsor Buzza ...................................................... 74 Memoir Roller Derby Dreams, by Audrey Word ................................................ -

Venice-Aerial-Tour

Venice and Veneto D E TAIL S Duration: 20-minutes flight Venice Aerial Tour Availability: Daily Price: € Additional guests: € Additional time: € Transfer: € CONTACT ME Agent Name Ph: Mob: Email: Rise above the terracotta roofs of Venice for a view of the mosaic- esque jungle of palazzi and cathedrals and islands dotted across the lagoon. Private tour 20-minutes flight English first Family friendly, Kids Itinerary Lido di Venezia Torcello Island Piazza San Marco Burano Island Arsenale South Murano island Arsenale North REASONS TO BOOK THIS EXPERIENCE What’s Included Hovering over the floating islands of Venice Private boat Expert guide Enjoying an aerial view of the Artisan demonstrations brightly colored palaces on Burano Entry tickets to the Torcello Cathedral Seeing the stunning Basilica di San Marco and Palazzo Ducale from above ITALY IS BEAUTIFUL LIKE NEVER BEFORE We cannot wait to welcome you to the most beautiful country in the world. In compliance with our Covid-free policy, we will provide full assistance and flexibility. We will also accept reservations and allow cancellations even if given at short notice. OUR RESERVATION AND CANCELLATION POLICY We accept reservations and allows cancellations with a 100% refund up to 48h. Please note this might not include entrance tickets booked in advance. Furthermore, you can reschedule for any time without any additional costs. USEFUL INFO Meeting point . You will receive a custom link once your booking is confirmed. Note should you require any further information, please don’t hesitate to contact us Agent Name Mob: Ph: Email:. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL Or LAST) JUDGMENT

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL or LAST) JUDGMENT Beloved Father of Mercy and Justice, We Your children, offer our lives as a pure and holy sacrifice, uniting our lives and our death to the life and death of Your Son and our Savior. At the Final Judgment we will stand united with the Body of Christ, body and soul, to receive Your Son's judgment. We will face this last and definitive judgment unafraid as the Books of Works are opened to reveal the imperishable deeds of love and mercy accumulated by the Church. This is the treasure stored up for eternity which Your children offer in the name of Christ our Savior and Redeemer. Send Your Holy Spirit, Lord, to lead us in this lesson of our study on the Eight Last Things. We pray in the name of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. + + + While I was watching thrones were set in place and one most venerable took his seat. His robe was white as snow, the hair of his head as pure as wool. His throne was a blaze of flames; its wheels were a burning fire. A stream of fire poured out, issuing from his presence. A thousand thousand waited on him, ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him. The court was in session and the books lay open. Daniel 7:9-10 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; and, because he is the Son of man, has granted him power to give judgment. -

S H a P E S O F a P O C a Ly P

Shapes of Apocalypse Arts and Philosophy in Slavic Thought M y t h s a n d ta b o o s i n R u s s i a n C u lt u R e Series Editor: Alyssa DinegA gillespie—University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana Editorial Board: eliot Borenstein—New York University, New York Julia BekmAn ChadagA—Macalester College, St. Paul, Minnesota nancy ConDee—University of Pittsburg, Pittsburg Caryl emerson—Princeton University, Princeton Bernice glAtzer rosenthAl—Fordham University, New York marcus levitt—USC, Los Angeles Alex Martin—University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana irene Masing-DeliC—Ohio State University, Columbus Joe pesChio—University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee irina reyfmAn—Columbia University, New York stephanie SanDler—Harvard University, Cambridge Shapes of Apocalypse Arts and Philosophy in Slavic Thought Edited by Andrea OppO BOSTON / 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-61811-174-6 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-618111-968 (electronic) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Konstantin Juon, “The New Planet,” 1921. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. -

Ferrara Di Ferrara

PROVINCIA COMUNE DI FERRARA DI FERRARA Visit Ferraraand its province United Nations Ferrara, City of Educational, Scientific and the Renaissance Cultural Organization and its Po Delta Parco Urbano G. Bassani Via R. Bacchelli A short history 2 Viale Orlando Furioso Living the city 3 A year of events CIMITERO The bicycle, queen of the roads DELLA CERTOSA Shopping and markets Cuisine Via Arianuova Viale Po Corso Ercole I d’Este ITINERARIES IN TOWN 6 CIMITERO EBRAICO THE MEDIAEVAL Parco Corso Porta Po CENTRE Via Ariosto Massari Piazzale C.so B. Rossetti Via Borso Stazione Via d.Corso Vigne Porta Mare ITINERARIES IN TOWN 20 Viale Cavour THE RENAISSANCE ADDITION Corso Ercole I d’Este Via Garibaldi ITINERARIES IN TOWN 32 RENAISSANCE Corso Giovecca RESIDENCES Piazza AND CHURCHES Trento e Trieste V. Mazzini ITINERARIES IN TOWN 40 Parco Darsena di San Paolo Pareschi WHERE THE RIVER Piazza Travaglio ONCE FLOWED Punta della ITINERARIES IN TOWN 46 Giovecca THE WALLS Via Cammello Po di Volano Via XX Settembre Via Bologna Porta VISIT THE PROVINCE 50 San Pietro Useful information 69 Chiesa di San Giorgio READER’S GUIDE Route indications Along with the Pedestrian Roadsigns sited in the Historic Centre, this booklet will guide the visitor through the most important areas of the The “MUSEO DI QUALITÀ“ city. is recognised by the Regional Emilia-Romagna The five themed routes are identified with different colour schemes. “Istituto per i Beni Artistici Culturali e Naturali” Please, check the opening hours and temporary closings on the The starting point for all these routes is the Tourist Information official Museums and Monuments schedule distributed by Office at the Estense Castle. -

Paradise in the Qur'an and the Music of Apocalypse

CHAPTER 6 Paradise in the Quran and the Music of Apocalypse Todd Lawson These people have no grasp of God’s true measure. On the Day of Resurrection, the whole earth will be in His grip. The heavens will be rolled up in His right hand – Glory be to Him! He is far above the partners they ascribe to Him! the Trumpet will be sounded, and everyone in the heavens and earth will fall down senseless except those God spares. It will be sounded once again and they will be on their feet, looking on. The earth will shine with the light of its Lord; the Record of Deeds will be laid open; the prophets and witnesses will be brought in. Fair judgment will be given between them: they will not be wronged and every soul will be repaid in full for what it has done. He knows best what they do. Q 39:67–70 … An apocalypse is a supernatural revelation, which reveals secrets of the heavenly world, on the one hand, and of eschatological judgment on the other. John J. Collins, The Dead Sea Scrolls 150 ∵ The Quran may be distinguished from other scriptures of Abrahamic or ethical monotheistic faith traditions by a number of features. The first of these is the degree to which the subject of revelation (as it happens, the best English trans- lation of the Greek word ἀποκάλυψις / apocalypsis) is central to its form and contents. In this the Quran is unusually self-reflective, a common feature, inci- dentally, of modern and postmodern works of art and literature. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Raising the Last Hope British Romanticism and The

RAISING THE LAST HOPE BRITISH ROMANTICISM AND THE RESURRECTION OF THE DEAD, 1780-1830 by DANIEL R. LARSON B.A., University of New Mexico, 2009 M.A., University of New Mexico, 2011 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English 2016 This thesis entitled: “Raising the Last Hope: British Romanticism and the Resurrection of the Dead, 1780-1830” written by Daniel Larson has been approved for the Department of English Jeffrey Cox Jill Heydt-Stevenson Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ABSTRACT Larson, Daniel R. (Ph.D., English) Raising the Last Hope: British Romanticism and the Resurrection of the Dead, 1780-1830 Thesis directed by Professor Jeffrey N. Cox This dissertation examines the way the Christian doctrine of bodily resurrection surfaces in the literature of the British Romantic Movement, and investigates the ways literature recovers the politically subversive potential in theology. In the long eighteenth century, the orthodox Christian doctrine of bodily resurrection (historically, a doctrine that grounded believers’ resistance to state oppression) disappears from the Church of England’s theological and religious dialogues, replaced by a docile vision of disembodied life in heaven—an afterlife far more amenable to political power. However, the resurrection of the physical body resurfaces in literary works, where it can again carry a powerful resistance to the state. -

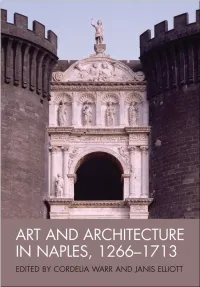

Art and Architecture in Naples, 1266-1713 / Edited by Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott

This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 NEW APPROACHES EDITED BY CORDELIA WARR AND JANIS ELLIOTT This edition first published 2010 r 2010 Association of Art Historians Originally published as Volume 31, Issue 4 of Art History Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley- Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. -

Proceedings of the Colloquium on Paradise and Hell in Islam Keszthely, 7-14 July 2002

Proceedings of the Colloquium on Paradise and Hell in Islam Keszthely, 7-14 July 2002 - Part One - EDITED BY K DÉVÉNYI - A. FODOR THE ARABIST BUDAPEST STUDIES IN ARABIC 28-29 THE ARABIST BUDAPEST STUDIES IN ARABIC 28-29 Proceedings of the Colloquium on Paradise and Hell in Islam Keszthely, 7-14 July 2002 EDITOR ALEXANDER FODOR - Part One - ASSOCIATE EDITORS KINGA DÉVÉNYI TAMÁS IVÁNYI EDITED BY K. DÉVÉNYI - A. FODOR EÖTVÖS LORÁND UNIVERSITY CHAIR FOR ARABIC STUDIES & CSOMA DE KŐRÖS SOCIETY SECTION OF ISLAMIC STUDIES Copyright Ed. Csorna de Kőrös Soc. 2008 MÚZEUM BLD. 4/B BUDAPEST, 1088 HUNGARY BUDAPEST, 2008 THE ARABIST CONTENTS BUDAPEST STUDIES IN ARABIC 28-29 P reface........................................................................................................................................ vii Patricia L. Baker (London): Fabrics Fit for A ngels ............................................................... 1 Sheila S. Blair (Boston): Ascending to Heaven: Fourteenth-century Illustrations of the Prophet’s Micra g ......................................................................................................... 19 Jonathan M. Bloom (Boston): Paradise as a Garden, the Garden as Garden . 37 Giovanni Canova (Naples): Animals in Islamic Paradise and H ell ...................... 55 István Hajnal (Budapest): The Events o f Paradise: Facts and Eschatological Doctrines in the Medieval Isma'ili History ................................................................................ 83 Alan Jones (Oxford): Heaven and Hell in the