Raising the Last Hope British Romanticism and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doubles and Doubling in Tarchetti, Capuana, and De Marchi By

Uncanny Resemblances: Doubles and Doubling in Tarchetti, Capuana, and De Marchi by Christina A. Petraglia A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Italian) At the University of Wisconsin-Madison 2012 Date of oral examination: December 12, 2012 Oral examination committee: Professor Stefania Buccini, Italian Professor Ernesto Livorni (advisor), Italian Professor Grazia Menechella, Italian Professor Mario Ortiz-Robles, English Professor Patrick Rumble, Italian i Table of Contents Introduction – The (Super)natural Double in the Fantastic Fin de Siècle…………………….1 Chapter 1 – Fantastic Phantoms and Gothic Guys: Super-natural Doubles in Iginio Ugo Tarchetti’s Racconti fantastici e Fosca………………………………………………………35 Chapter 2 – Oneiric Others and Pathological (Dis)pleasures: Luigi Capuana’s Clinical Doubles in “Un caso di sonnambulismo,” “Il sogno di un musicista,” and Profumo……………………………………………………………………………………..117 Chapter 3 – “There’s someone in my head and it’s not me:” The Double Inside-out in Emilio De Marchi’s Early Novels…………………..……………………………………………...222 Conclusion – Three’s a Fantastic Crowd……………………...……………………………322 1 The (Super)natural Double in the Fantastic Fin de Siècle: The disintegration of the subject is most often underlined as a predominant trope in Italian literature of the Twentieth Century; the so-called “crisi del Novecento” surfaces in anthologies and literary histories in reference to writers such as Pascoli, D’Annunzio, Pirandello, and Svevo.1 The divided or multifarious identity stretches across the Twentieth Century from Luigi Pirandello’s unforgettable Mattia Pascal / Adriano Meis, to Ignazio Silone’s Pietro Spina / Paolo Spada, to Italo Calvino’s il visconte dimezzato; however, its precursor may be found decades before in such diverse representations of subject fissure and fusion as embodied in Iginio Ugo Tarchetti’s Giorgio, Luigi Capuana’s detective Van-Spengel, and Emilio De Marchi’s Marcello Marcelli. -

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly. -

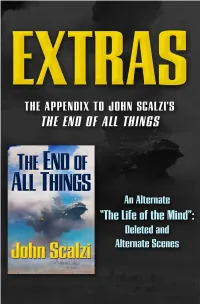

The End of All Things Took Me Longer to Write Than Most of My Books Do, in Part Because I Had a Number of False Starts

AN ALTERNATE “THE LIFE OF THE MIND” Deleted and Alternate Scenes ■■ ■■ 039-61734_ch01_4P.indd 351 06/09/15 6:17 am Introduction The End of All Things took me longer to write than most of my books do, in part because I had a number of false starts. These false starts weren’t bad—in my opinion— and they were use- ful in helping me fi gure out what was best for the book; for ex- ample, determining which point- of- view characters I wanted to have, whether the story should be in fi rst or third person, and so on. But at the same time it’s annoying to write a bunch of stuff and then go Yeaaaaah, that’s not it. So it goes. Through vari ous false starts and diversions, I ended up writ- ing nearly 40,000 words— almost an entire short novel!—of material that I didn’t directly use. Some of it was re cast and repurposed in different directions, and a lot of it was simply left to the side. The thing is when I throw something out of a book, I don’t just delete it. I put it into an “excise fi le” and keep it just in case it’ll come in handy later. Like now: I’ve taken vari ous bits from the excise fi le and with them have crafted a fi rst chapter of an alternate version of The Life of the Mind, the fi rst novella of The End of All Things. This version (roughly) covers the same events, with (roughly) the same characters, but with a substantially different narrative di- rection. -

Scanned Using Scannx OS16000 PC

/' \ / / SAGAR 2017-2018 CHIEF EDITORS Sundas Amer, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Charlotte Giles, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Paromita Pain, Dept, of Journalism, UT Austin ^ EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE MEMBERS Nabeeha Chaudhary, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin Andrea Guiterrez, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Hamza Muhammad Iqbal, Comparative Literature, UT Austin Namrata Kanchan, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Kathleen Longwaters, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Daniel Ng, Anthropology, UT Austin Kathryn North, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Joshua Orme, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin David St. John, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Ramna Walia, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin WEB EDITOR Charlotte Giles & Paromita Pain PRINTDESIGNER Dana Johnson EDITORIAL ADVISORS Donald R. Davis, Jr., Director, UT South Asia Institute; Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Rachel S. Meyer, Assistant Director, UT South Asia Institute EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Barnett, Associate Professor, Dept, of History, University of Virginia Eric Lewis Beverley, Assistant Professor, Dept, of History, SUNY Stonybrook Purmma Bose, Associate Professor, Dept, of English, Indiana University-Bloomineton Laura Brueck, Assomate Professor, Asian Languages & Cultures Dept., Northwestern University Indrani Chatterjee, Dept, of History, UT-Austin uiuversiiy Lalitha Gopalan, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-TV-Film, UT-Austin Sumit Guha, Dept, of History, UT-Austin Kathryn Hansen, Professor Emerita, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Barbara Harlow, Professor, Dept, of English, UT-Austin Heather Hindman, Assistant Professor, Dept, of Anthropology, UT-Austin Syed Akbar Hyder, Associate Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Shanti Kumar, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-Television-Film, UT-Austin Janice Leoshko, Associate Professor, Dept, of Art and Art History, UT-Austin W. -

Paradise in the Qur'an and the Music of Apocalypse

CHAPTER 6 Paradise in the Quran and the Music of Apocalypse Todd Lawson These people have no grasp of God’s true measure. On the Day of Resurrection, the whole earth will be in His grip. The heavens will be rolled up in His right hand – Glory be to Him! He is far above the partners they ascribe to Him! the Trumpet will be sounded, and everyone in the heavens and earth will fall down senseless except those God spares. It will be sounded once again and they will be on their feet, looking on. The earth will shine with the light of its Lord; the Record of Deeds will be laid open; the prophets and witnesses will be brought in. Fair judgment will be given between them: they will not be wronged and every soul will be repaid in full for what it has done. He knows best what they do. Q 39:67–70 … An apocalypse is a supernatural revelation, which reveals secrets of the heavenly world, on the one hand, and of eschatological judgment on the other. John J. Collins, The Dead Sea Scrolls 150 ∵ The Quran may be distinguished from other scriptures of Abrahamic or ethical monotheistic faith traditions by a number of features. The first of these is the degree to which the subject of revelation (as it happens, the best English trans- lation of the Greek word ἀποκάλυψις / apocalypsis) is central to its form and contents. In this the Quran is unusually self-reflective, a common feature, inci- dentally, of modern and postmodern works of art and literature. -

St.-Thomas-Aquinas-The-Summa-Contra-Gentiles.Pdf

The Catholic Primer’s Reference Series: OF GOD AND HIS CREATURES An Annotated Translation (With some Abridgement) of the SUMMA CONTRA GENTILES Of ST. THOMAS AQUINAS By JOSEPH RICKABY, S.J., Caution regarding printing: This document is over 721 pages in length, depending upon individual printer settings. The Catholic Primer Copyright Notice The contents of Of God and His Creatures: An Annotated Translation of The Summa Contra Gentiles of St Thomas Aquinas is in the public domain. However, this electronic version is copyrighted. © The Catholic Primer, 2005. All Rights Reserved. This electronic version may be distributed free of charge provided that the contents are not altered and this copyright notice is included with the distributed copy, provided that the following conditions are adhered to. This electronic document may not be offered in connection with any other document, product, promotion or other item that is sold, exchange for compensation of any type or manner, or used as a gift for contributions, including charitable contributions without the express consent of The Catholic Primer. Notwithstanding the preceding, if this product is transferred on CD-ROM, DVD, or other similar storage media, the transferor may charge for the cost of the media, reasonable shipping expenses, and may request, but not demand, an additional donation not to exceed US$25. Questions concerning this limited license should be directed to [email protected] . This document may not be distributed in print form without the prior consent of The Catholic Primer. Adobe®, Acrobat®, and Acrobat® Reader® are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Limits, Malice and the Immortal Hulk

https://lthj.qut.edu.au/ LAW, TECHNOLOGY AND HUMANS Volume 2 (2) 2020 https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.1581 Before the Law: Limits, Malice and The Immortal Hulk Neal Curtis The University of Auckland, New Zealand Abstract This article uses Kafka's short story 'Before the Law' to offer a reading of Al Ewing's The Immortal Hulk. This is in turn used to explore our desire to encounter the Law understood as a form of completeness. The article differentiates between 'the Law' as completeness or limitlessness and 'the law' understood as limitation. The article also examines this desire to experience completeness or limitlessness in the work of George Bataille who argued such an experience was the path to sovereignty. In response it also considers Francois Flahault's critique of Bataille who argued Bataille failed to understand limitlessness is split between a 'good infinite' and a 'bad infinite', and that it is only the latter that can ultimately satisfy us. The article then proposes The Hulk, especially as presented in Al Ewing's The Immortal Hulk, is a study in where our desire for limitlessness can take us. Ultimately it proposes we turn ourselves away from the Law and towards the law that preserves and protects our incompleteness. Keywords: Law; sovereignty; comics; superheroes; The Hulk Introduction From Jean Bodin to Carl Schmitt, the foundation of the law, or what we more readily understand as sovereignty, is marked by a significant division. The law is a limit in the sense of determining what is permitted and what is proscribed, but the authority for this limit is often said to derive from something unlimited. -

Proceedings of the Colloquium on Paradise and Hell in Islam Keszthely, 7-14 July 2002

Proceedings of the Colloquium on Paradise and Hell in Islam Keszthely, 7-14 July 2002 - Part One - EDITED BY K DÉVÉNYI - A. FODOR THE ARABIST BUDAPEST STUDIES IN ARABIC 28-29 THE ARABIST BUDAPEST STUDIES IN ARABIC 28-29 Proceedings of the Colloquium on Paradise and Hell in Islam Keszthely, 7-14 July 2002 EDITOR ALEXANDER FODOR - Part One - ASSOCIATE EDITORS KINGA DÉVÉNYI TAMÁS IVÁNYI EDITED BY K. DÉVÉNYI - A. FODOR EÖTVÖS LORÁND UNIVERSITY CHAIR FOR ARABIC STUDIES & CSOMA DE KŐRÖS SOCIETY SECTION OF ISLAMIC STUDIES Copyright Ed. Csorna de Kőrös Soc. 2008 MÚZEUM BLD. 4/B BUDAPEST, 1088 HUNGARY BUDAPEST, 2008 THE ARABIST CONTENTS BUDAPEST STUDIES IN ARABIC 28-29 P reface........................................................................................................................................ vii Patricia L. Baker (London): Fabrics Fit for A ngels ............................................................... 1 Sheila S. Blair (Boston): Ascending to Heaven: Fourteenth-century Illustrations of the Prophet’s Micra g ......................................................................................................... 19 Jonathan M. Bloom (Boston): Paradise as a Garden, the Garden as Garden . 37 Giovanni Canova (Naples): Animals in Islamic Paradise and H ell ...................... 55 István Hajnal (Budapest): The Events o f Paradise: Facts and Eschatological Doctrines in the Medieval Isma'ili History ................................................................................ 83 Alan Jones (Oxford): Heaven and Hell in the -

Dressing in American Telefantasy

Volume 5, Issue 2 September 2012 Stripping the Body in Contemporary Popular Media: the value of (un)dressing in American Telefantasy MANJREE KHAJANCHI, Independent Researcher ABSTRACT Research perspectives on identity and the relationship between dress and body have been frequently studied in recent years (Eicher and Roach-Higgins, 1992; Roach-Higgins and Eicher, 1992; Entwistle, 2003; Svendsen, 2006). This paper will make use of specific and detailed examples from the television programmes Once Upon a Time (2011- ), Falling Skies (2011- ), Fringe (2008- ) and Game of Thrones (2011- ) to discover the importance of dressing and accessorizing characters to create humanistic identities in Science Fiction and Fantastical universes. These shows are prime case studies of how the literal dressing and undressing of the body, as well as the aesthetic creation of television worlds (using dress as metaphor), influence perceptions of personhood within popular media programming. These four shows will be used to examine three themes in this paper: (1) dress and identity, (2) body and world transformations, and (3) (non-)humanness. The methodological framework of this article draws upon existing academic literature on dress and society, combined with textual analysis of the aforementioned Telefantasy shows, focussing primarily on the three themes previously mentioned. This article reveals the role transformations of the body and/or the world play in American Telefantasy, and also investigates how human and near-human characters and settings are fashioned. This will invariably raise questions about what it means to be human, what constitutes belonging to society, and the connection that dress has to both of these concepts. KEYWORDS Aesthetics, Body, Dress, Falling Skies, Fringe, Game of Thrones, Identity, Once Upon a Time, Telefantasy. -

Duality and Reflections in Stephen King's Writers Alexis Hitchcock

ABSTRACT A Dark Mirror: Duality and Reflections in Stephen King's Writers Alexis Hitchcock Director: Dr. Lynne Hinojosa, Ph.D. Stephen King is well known for popular horror fiction but has recently been addressed more thoroughly by literary critics. While most studies focus on horror themes and the relationships between various characters, this thesis explores the importance of the author characters in three works by Stephen King: Misery, The Dark Half, and The Shining. The introduction gives a background of Stephen King as an author of popular horror fiction and discusses two themes that are connected to his author characters: doppelgängers and duality, and the idea of the death of the author. The death of the author is the idea that an author's biography should not affect the interpretation of a text. Implicit in this idea is the notion that the separation of an author from his work makes the text more literary and serious. The second chapter on Misery explores the relationship between the author and the readership or fans and discusses Stephen King’s divide caused by his split between his talent as an author of popular fiction and a desire to be a writer of literary fiction. The third chapter concerning The Dark Half explores Stephen King’s use of the pseudonym Richard Bachman and the splitting this created within himself and the main character of his novel. The last chapter includes discussion of The Shining and the author character’s split in personality caused by alcohol and supernatural sources. Studying the author characters and their doppelgängers reveals the unique stance King takes on the “death of the author” idea and shows how he represents the splitting of the self within his works. -

Reflected Shadows: Folklore and the Gothic ABSTRACTS

Reflected Shadows: Folklore and the Gothic ABSTRACTS Dr Gail-Nina Anderson (Independent Scholar) [email protected] Dracula’s Cape: Visual Synecdoche and the Culture of Costume. In 1939 Robert Bloch wrote a story called ‘The Cloak’ which took to its extreme a fashion statement already well established in popular culture – vampires wear cloaks. This illustrated paper explores the development of this motif, which, far from having roots in the original vampire lore of Eastern Europe, demonstrates a complex combination of assumptions about vampires that has been created and fed by the fictional representations in literature and film.While the motif relates most immediately to perceptions of class, demonic identity and the supernatural, it also functions within the pattern of nostalgic reference that defines the vampire in modern folklore and popular culture. The cloak belongs to that Gothic hot-spot, the 1890s, but also to Bela Lugosi, to modern Goth culture and to that contemporary paradigm of ready-fit monsters, the Halloween costume shop, taking it, and its vampiric associations, from aristocratic attire to disposable disguise. Biography: Dr Gail-Nina Anderson is a freelance lecturer who runs daytime courses aimed at enquiring adult audiences and delivers a programme of public talks for Newcastle’s Literary and Philosophical Library. She is also a regular speaker at the Folklore Society ‘Legends’ weekends, and in 2013 delivered the annual Katharine Briggs Lecture at the Warburg Institute, on the topic of Fine Art and Folklore. She specialises in the myth-making elements of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and the development of Gothic motifs in popular culture.