Limits, Malice and the Immortal Hulk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

The North Turns Rocks to Riches with Mining and Exploration

The North turns rocks to riches with mining and exploration NORTHWEST TERRITORIES & NUNAVUT CHAMBER OF MINES Explore for More: Table of Contents Exploration starts here! ..................................................................2 Environment – highest level of protection .....................31 Giant mine – a big role in defining Yellowknife ....................32 Mining North Works! for Canada’s Environmental legacy ...........................................................................32 Northwest Territories and Nunavut .......................................3 Leading the way through government legislation .............33 Minerals are the North’s economic advantage ...................... 4 Climate change – mining has important role to play ...... 34 Northern rocks – a diverse and vast geology .......................... 5 Infrastructure legacy – building makes it better .................35 Rich mining history and legacy ......................................................... 6 Geologic time scale spans over four billion years ............... 7 Minerals in our lives – what do we make Exploration and mining span several centuries .................... 8 from them? ...........................................................................................36 Cobalt .........................................................................................................36 Mineral resources cycle – how it works ............................10 Diamonds .................................................................................................36 -

The Avengers (Action) (2012)

1 The Avengers (Action) (2012) Major Characters Captain America/Steve Rogers...............................................................................................Chris Evans Steve Rogers, a shield-wielding soldier from World War II who gained his powers from a military experiment. He has been frozen in Arctic ice since the 1940s, after he stopped a Nazi off-shoot organization named HYDRA from destroying the Allies with a mystical artifact called the Cosmic Cube. Iron Man/Tony Stark.....................................................................................................Robert Downey Jr. Tony Stark, an extravagant billionaire genius who now uses his arms dealing for justice. He created a techno suit while kidnapped by terrorist, which he has further developed and evolved. Thor....................................................................................................................................Chris Hemsworth He is the Nordic god of thunder. His home, Asgard, is found in a parallel universe where only those deemed worthy may pass. He uses his magical hammer, Mjolnir, as his main weapon. The Hulk/Dr. Bruce Banner..................................................................................................Mark Ruffalo A renowned scientist, Dr. Banner became The Hulk when he became exposed to gamma radiation. This causes him to turn into an emerald strongman when he loses his temper. Hawkeye/Clint Barton.........................................................................................................Jeremy -

Marvel/ Dc Secret Files A.R.G.U.S / S.H.I.E.L.D

MARVEL/ DC SECRET FILES During these sessions you will take place of one of these superheroes from both worlds to discuss the take on action, the strategy, explain the reasons to proceed from certain way and giving enough intelligence and ideas to approach conflicted countries and regions where certain heroes from an specific nationality couldn’t enter due to political motives. OVERVIEW Dangerous objects and devices have fallen into the hands of both Marvel and DC villains. It is the mission of the UN to assign rescue missions of these objects located in different parts of both universes to avoid a possible collision of worlds and being used against humanity. The General Assembly of the United Nations and the Security Council has given special powers to heroes of different countries (and universes) to take action on behalf of the governments of the world to avoid a catastrophe and to be able to fight with the opposing forces that have taken possession of these devices, threatening humanity with them and disrupting world peace forming a Special Force. Recon missions have been done by Black Widow, Catwoman, Hawkeye and Plastic Man and we have gathered information of different objects that are guarded by villains in different locations of both universes. Some in the Marvel universe and others in the DC universe. Each artifact has been enclosed in a magic bubble that prevents its use to any being that has possession of it. But this enchantment created by Doctor Strange and Doctor Fate has expiration time. Within 48 hours, it will be deactivated and anyone who has any of these devices in their possession will be able to freely use them. -

X-Men: Apocalypse' Succeeds Thanks to Its Rich Characters

http://www.ocolly.com/entertainment_desk/x-men-apocalypse-succeeds-thanks-to-its-rich- characters/article_ffbc145a-251d-11e6-9b66-f38ca28933de.html 'X-Men: Apocalypse' succeeds thanks to its rich characters Brandon Schmitz, Entertainment Reporter, @SchmitzReviews May 28, 2016 20th Century FOX It's amazing to think that Fox's "X-Men" saga has endured for more than a decade and a half with only a couple of stumbles. From the genre- revitalizing first film to the exceptionally intimate "Days of Future Past," the series has definitely made its mark on the blockbuster landscape. With "Apocalypse," director Bryan Singer returns for his fourth time at the helm. Similarly to his previous outing, this movie is loosely based on one of the superhero team's most popular comic book storylines. Ten years have passed since Charles Xavier (James McAvoy) and friends averted the rise of the Sentinels. However, altering the course of the "X- Men" continuity has merely replaced one disaster with another. The world's first mutant, Apocalypse (Oscar Isaac), was worshipped as a god around the dawn of civilization. Thanks to abilities he has taken from other mutants, he is virtually immortal. Following thousands of years of slumber, Apocalypse wakes to find a world ruled by people who he feels are weak. Namely, humans. Dissatisfied with earth's warring nations, the near-all-powerful mutant sets out to cleanse the world with his four "horsemen." In the wake of this new threat, Mystique (Jennifer Lawrence) must lead a young X-Men team comprised of familiar faces such as Cyclops (Tye Sheridan) and Jean Grey (Sophie Turner). -

Comunicado De Novedadesnoviembre 2012

TM & © DC Comics COMUNICADO DE NOVEDADES NOVIEMBRE 2012 lA NOCHE de los búhos TM & © DC Comics lA NOCHE de los búhos Comienza... lA NOCHE de los búhos El Tribunal de los Búhos decidió abandonar las sombras del anonimato no solo para derrotar al Hombre Murciélago, sino también para reclamar un dominio sobre la ciudad que dicen merecer. Para ello, orquestaron un ataque a la Mansión Wayne, mientras un auténtico ejército de Garras se desplegaba por las calles BATMAN núm. 7 de Gotham, con la intención de terminar con la vida de hasta 40 individuos que, • Guion: Judd Winick, Gail Simone, Peter J. Tomasi con su liderazgo y personalidad, dan • Dibujo: Ardian Syaf, Lee Garbett, Marcus To, Andy Clarke forma a la ciudad. Una amenaza que • Edición original: Batwing núm. 9, Batgirl núm. 9, Batman and Robin núm. 9 USA - DC requerirá la intervención de los más Comics cercanos colaboradores del Caballero • Periodicidad: Mensual Oscuro. • Formato: Grapa, 64 págs. Color. 168x257 mm. • PVP: 4,50 € WWW.eccediciones.com 9 7 8 8 4 1 5 6 2 8 8 1 1 lA NOCHE de los búhos TM & © DC Comics lA NOCHE de los búhos El prólogo a la saga más aclamada lA NOCHE de los búhos El misterioso Saiko tiene como objetivo matar a Dick Grayson, a quien acusa de ser “el asesino más fiero de Gotham”. El villano ha liquidado ya a C.C. Haly, el dueño del circo que vio crecer a Dick antes de que se convirtiera en Robin y NIGHTWING núm. 2 donde sus padres murieron. Siguiendo una pista que le proporcionó Haly junto • Guion: Kyle Higgins a las escrituras del circo, Nightwing ha • Dibujo: Eddy Barrows, Eduardo Pansica, Geraldo Borges encontrado un antiguo y enigmático • Edición original: Nightwing núms. -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

Avengers and Its Applicability in the Swedish EFL-Classroom

Master’s Thesis Avenging the Anthropocene Green philosophy of heroes and villains in the motion picture tetralogy The Avengers and its applicability in the Swedish EFL-classroom Author: Jens Vang Supervisor: Anne Holm Examiner: Anna Thyberg Date: Spring 2019 Subject: English Level: Advanced Course code: 4ENÄ2E 2 Abstract This essay investigates the ecological values present in antagonists and protagonists in the narrative revolving the Avengers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The analysis concludes that biocentric ideals primarily are embodied by the main antagonist of the film series, whereas the protagonists mainly represent anthropocentric perspectives. Since there is a continuum between these two ideals some variations were found within the characters themselves, but philosophical conflicts related to the environment were also found within the group of the Avengers. Excerpts from the films of the study can thus be used to discuss and highlight complex ecological issues within the EFL-classroom. Keywords Ecocriticism, anthropocentrism, biocentrism, ecology, environmentalism, film, EFL, upper secondary school, Avengers, Marvel Cinematic Universe Thanks Throughout my studies at the Linneaus University of Vaxjo I have become acquainted with an incalculable number of teachers and peers whom I sincerely wish to thank gratefully. However, there are three individuals especially vital for me finally concluding my studies: My dear mother; my highly supportive girlfriend, Jenniefer; and my beloved daughter, Evie. i Vang ii Contents 1 Introduction -

Disney, Marvel and the Value of “Hidden Assets”

Strategy & Leadership M&A deal-making: Disney, Marvel and the value of “hidden assets” Joseph Calandro Jr., Article information: To cite this document: Joseph Calandro Jr., (2019) "M&A deal-making: Disney, Marvel and the value of “hidden assets”", Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 47 Issue: 3, pp.34-39, https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-02-2019-0023 Permanent link to this document: https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-02-2019-0023 Downloaded on: 04 July 2019, At: 04:22 (PT) References: this document contains references to 0 other documents. To copy this document: [email protected] The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 171 times since 2019* Users who downloaded this article also downloaded: (2010),"Disney's Marvel acquisition: a strategic financial analysis", Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 38 Iss 2 pp. 42-51 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/10878571011029055">https://doi.org/10.1108/10878571011029055</a> (2007),"From beast to beauty: The culture makeover at Walt Disney", Strategic Direction, Vol. 23 Iss 9 pp. 5-8 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/02580540710779681">https://doi.org/10.1108/02580540710779681</a> Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by Token:Eprints:NwQ4NzDCSiNhuBSqG8MG: For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. -

Batman’S Story

KNI_T_01_p01 CS6.indd 1 10/09/2020 10:14 IN THIS ISSUE YOUR PIECE Meet your white king – the latest 3 incarnation of the World’s Greatest Detective, the Dark Knight himself. PROFILE From orphan to hero, from injury 4 to resurrection; this is Batman’s story. GOTHAM GUIDE Insights into the Batman’s sanctum and 10 operational centre, a place of history, hi-tech devices and secrets. RANK & FILE Why the Dark Knight of Gotham is a 12 king – his knowledge, assessments and regal strategies. RULES & MOVES An indispensable summary of a king’s 15 mobility and value, and a standard move. Editor: Simon Breed Thanks to: Art Editor: Gary Gilbert Writers: Frank Miller, David Mazzucchelli, Writer: Alan Cowsill Grant Morrison, Jeph Loeb, Dennis O’Neil. Consultant: Richard Jackson Pencillers: Brett Booth, Ben Oliver, Marcus Figurine Sculptor: Imagika Sculpting To, Adam Hughes, Jesus Saiz, Jim Lee, Studio Ltd Cliff Richards, Mark Bagley, Lee Garbett, Stephane Roux, Frank Quitely, Nicola US CUSTOMER SERVICES Scott, Paulo Siqueira, Ramon Bachs, Tony Call: +1 800 261 6898 Daniel, Pete Woods, Fernando Pasarin, J.H. Email: [email protected] Williams III, Cully Hamner, Andy Kubert, Jim Aparo, Cameron Stewart, Frazer Irving, Tim UK CUSTOMER SERVICES Sale, Yanick Paquette, Neal Adams. Call: +44 (0) 191 490 6421 Inkers: Rob Hunter, Jonathan Glapion, J.G. Email: [email protected] Jones, Robin Riggs, John Stanisci, Sandu Florea, Tom Derenick, Jay Leisten, Scott Batman created by Bob Kane Williams, Jesse Delperdang, Dick Giordano, with Bill Finger Chris Sprouse, Michel Lacombe. Copyright © 2020 DC Comics. BATMAN and all related characters and elements © and TM DC Comics. -

X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude Free

FREE X-MEN: AGE OF APOCALYPSE PRELUDE PDF Scott Lobdell,Jeph Loeb,Mark Waid | 264 pages | 01 Jun 2011 | Marvel Comics | 9780785155089 | English | New York, United States X-Men: Prelude to Age of Apocalypse by Scott Lobdell The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. About this product. New other. Make an offer:. Auction: New Other. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Buy It Now. Add X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude cart. Make Offer. Condition is Brand New. See all 3 brand new listings. About this product Product Information Legion, the supremely powerful son of Charles Xavier, wants to change the world, and he's travelled back in time to kill Magneto to do it Can the X-Men stop him, or will the world as we know it cease to exist? Additional Product Features Dewey Edition. Show X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude Show Less. Add to Cart. Any Condition Any Condition. See all 13 - All listings for this product. Ratings and Reviews Write a review. Most relevant reviews. Thanks Thanks Verified purchase: Yes. Suess Beginners Book Collection by Dr. SuessHardcover 4. -

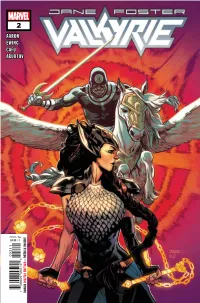

Aaron Ewing Cafu Aburtov

AARON ABURTOV CAFU EWING RATED RATED 0 0 2 1 1 $3.99 2 US T+ 7 59606 09515 5 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! ONCE SHE WAS THE MIGHTY THOR. NOW DR. JANE FOSTER WIELDS NOT THUNDER, BUT DEATH. AND LIFE. AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN. SHE IS THE LAST OF THE VALKYRIES—WARRIOR GODDESSES WHO FERRY THE SOULS OF THOSE WHO FALL IN BATTLE TO VALHALLA, THE LAND OF THE HONORED DEAD. WIELDER OF UNDRJARN THE ALL-WEAPON, DEFENDER OF MIDGARD AND ASGARD ALIKE, SHE IS… IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE WAR OF THE REALMS, EARTH’S VILLAINS ARE OUT TO OBTAIN THE MAGICAL WEAPONS LEFT BEHIND—INCLUDING DRAGONFANG, THE SWORD OF THE LATE LEADER OF THE VALKYRIES, BRUNNHILDE. JANE HAS SWORN TO RECOVER THE SWORD, BUT HER NEW ROLE AS VALKYRIE IS COMPLICATING HER MORTAL LIFE: DUE TO HER REPEATED UNEXPLAINED ABSENCES FROM THE HOSPITAL WHERE SHE WORKS, JANE HAS BEEN DEMOTED TO WORKING IN THE MORGUE. STILL, THERE ARE WORSE PLACES FOR A VALKYRIE TO BE. WHEN A DEAD BODY PROVIDES A CLUE TO DRAGONFANG’S WHEREABOUTS, JANE CALLS ON HEIMDALL THE ALL-SEEING, WHO HELPS HER ACTIVATE HER “VALKYRIE VISION,” WHICH REVEALS THE URGENCY OF ANY INDIVIDUAL’S DEATH. BUT BY THE TIME SHE TURNS THIS SIGHT ON HEIMDALL HIMSELF, SHE IS ALREADY TOO LATE TO STOP THE ASSASSIN KNOWN AS BULLSEYE FROM RUNNING DRAGONFANG THROUGH HEIMDALL’S CHEST. “THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE” PART II WRITERS: ARTIST: COLOR ARTIST: LETTERER & PRODUCTION: JASON AARON & AL EWING CAFU JESUS ABURTOV VC’S JOE SABINO COVER ARTISTS: VARIANT COVER ARTISTS: MAHMUD ASRAR & MATTHEW WILSON KIM JACINTO & DAVID CURIEL LOGO: ASSOC.