The Three Nephites, the Bodhisattva, and the Mahdi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Hypothesis Concerning the Three Days of Darkness Among the Nephites

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 2 Number 1 Article 8 1-31-1993 An Hypothesis concerning the Three Days of Darkness among the Nephites Russell H. Ball Atomic Energy Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Ball, Russell H. (1993) "An Hypothesis concerning the Three Days of Darkness among the Nephites," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol2/iss1/8 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title An Hypothesis concerning the Three Days of Darkness among the Nephites Author(s) Russell H. Ball Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2/1 (1993): 107–23. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract Aspects of the three days of darkness following the three-hour period of intense destruction described principally in 3 Nephi include: (1) the strange absence of rain among the destructive mechanisms described; (2) the source of the intense lightning, which seems to be unaccompanied by rain; (3) a mechanism to account for the inundation of the cities of Onihah, Mocum, and Jerusalem, which were not among the cities which “sunk in the depths of the sea”; and (4) the absence in the histories of contemporary European and Asiatic civilizations of corresponding events, which are repeat- edly characterized in 3 Nephi as affecting “the face of the whole earth.” An -Hypothesis concerning the Three Days ·of Darkness among the Nephites Russell H. -

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

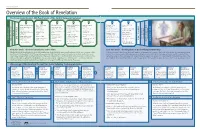

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Print Game Notes

No. 22 All-Time Victories NCAA Division I • 2 National Titles (NIT 1951, 1966) • 26 Conference Titles • 21 NCAA Tournaments • 30 Postseason Invitations 1 National Player of the Year • 2 Basketball Hall of Fame Inductees • 40 All-America Citations • 43 NBA Draft Selections • 98 All-Conference Citations BYU COUGAR BASKETBALL Game 10 — BYU vs. Eastern Washington BYU HOSTS EASTERN WASHINGTON TUESDAY 2005-06 BYU SCHEDULE/RESULTS BYU (6-3, 0-0 MWC) hosts two games in the Marriott Center this week, facing Eastern Washington (5-5, 0-0 Big Sky) Tuesday and Tulsa (4-6, 0-0 C-USA) Friday. Both games start at 7 p.m. Eastern Washington is coming of home NOVEMBER win over Cal Poly (76-62) after a loss at nationally ranked Gonzaga (75-65). The radio broadcast can be heard on 4 (Fri.) Victoria (exhibition) 81-54 W KSL Newsradio (102.7 FM/1160 AM) and the Cougar Sports Network with Greg Wrubell and Mark Durrant calling 10 (Thu.) Seattle Pacific (exhibition) 86-72 W the action. 18 (Fri.) Loyola Marymount 71-83 L 22 (Tue.) vs. Washington State (Spokane) 76-68 W TUESDAY IS FAMILY NIGHT 26 (Sat.) Southern Utah 86-61 W Tuesday’s BYU-Eastern Washington game includes a family night discount. A family of 5 can attend for $15, with a 30 (Wed.) vs. Lamar (Delta Center, SLC) 97-74 W $3 charge for each additional person. DECEMBER UP NEXT 3 (Sat.) @USC 68-74 L BYU hosts the Tulsa Golden Hurricanes (4-6, 0-0 C-USA) Friday at 7:05 p.m. -

The Nephites?

I believe that the Book of Mormon is indeed a book writtenfor our day, that it contains many powerful lessons that can greatly benefit us. I propose that a society that negatesfernaleness will likely be a society that is militaristic- or that a society that is militaristic will likely be a society that negatesfemaleness; whichever the cause and whichever the eflect, the result will be disaster: THE NEPHITES? By Carol Lynn Pearson LMOST EVERY TIME I HAVE MENTIONED THE That's as scary as it's going to get in this piece. "It's much easier title of this article to anyone, it has brought a standing hand in hand." Partnership. A laugh-not a laugh of derision, a laugh of delight. The In October 1992, I was invited to perform Mother Wove the very idea, mentioning woman-power and the Book of Morning on Crete at an international conference to celebrate Mormon in the same breath. Humor depends on the incon- partnership between women and men. While I was sitting in gruous, and what could be more incongruous than feminism the audience of about five hundred people from all over the and the Nephites? world, waiting to hear a talk by Margarita Papandreou, former Let me propose a very modest definition of feminism, one first lady of Greece (and who had invited me), I visited with that appears in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism: "Feminism is Hilkka, a striking Finnish woman who had represented her the philosophical belief that advocates the equality of women country at the United Nations. When I asked about her areas and men and seeks to remove inequities and to redress injus- of study, she said, "I'm doing some writing on the relationship tices against women."' between patriarchy and militarism. -

Islamochristiana

PONTIFICIO ISTITUTO DI STUD1 ARAB1 E D'ISLAMISTICA ISLAMOCHRISTIANA (ESTRATTO) MUHIB 0. OPELOYE CONFLUENCE AND CONFLICT IN THE QUR'ANIC AND BIBLICAL ACCOUNTS OF THE LIFE OF PROPHET MUSA 1990 ROMA MUHIB 0. OPELOYE * CONFLUENCE AND CONFLICT IN THE QUR'ANIC AND BIBLICAL ACCOUNTS OF THE LIFE OF PROPHET MOSA SUMMARY:The A. compares the qur'inic and biblical presentations of Moses. Though the Qur'in does not set out the prophet's life chronologically, a chronological account can be constructed from the various passages. It can be seen that this is very similar to the life of Moses as told by the Bible. The A. nevertheless lists seven points of dissimilarity. These he attributes to the different circumstances in which the message was recorded. The similarities, he suggests, indicate a common source and origin. Prophet Miisii (the Biblical Moses), otherwise known as Kalimu Iliihz, is the only prophet of God, apart from prophet Yiisuf, whose life account is given in detail by the Qur'Zn. Information on his life is mainly contained in Siirat al-Baqarah (2:49-71); Siirat al-A 'rcTf (7:10&162); Siirat Tiihi (20:9-97); Siirat ash-Shu'arii' (26:10-69) and SGrat al-Qi~a:r. (28:342), apart from other Qur'iinic passages where casual references are made to different aspects of his life. The special attention given to MiisZ by the Qur'iin derives perhaps from * Dr Muhib 0. Opeloye (born 1949) holds a Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from the University of Ilorin, Nigeria. For his thesis he presented A Comparative Study of Selected SocieTheolo~~ical Themes Common to the Qur'in and the Bible. -

The Book of Mormon and DNA Research: Essays from the Af Rms Review and the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Daniel C

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2008 The Book of Mormon and DNA Research: Essays from The aF rms Review and the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Daniel C. Peterson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, Daniel C., "The Book of Mormon and DNA Research: Essays from The aF rms Review and the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies" (2008). Maxwell Institute Publications. 81. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. H\Y6cc_cZAcfacbUbX8B5FYgYUfW\, the best of the maxwell, institute h\Y 6cc_ AcfacbcZ ½UbX½ 8B5FYgYUfW\ 9ggUmgZfcaBVS4/@;A@SdWSe UbXh\Y8]c`\OZ]T0]]Y]T;]`[]\AbcRWSa 9X]hYXVm8Ub]Y`7"DYhYfgcb The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Brigham Young University Provo, Utah Cover design by Jacob D. Rawlins The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Brigham Young University 200 WAIH Provo, UT 84602 © 2008 The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Book of Mormon and DNA research : essays from the Farms review and the Journal of Book of Mormon studies / edited by Daniel C. Peterson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Across Arabia with Lehi and Sariah: “Truth Shall Spring out of the Earth”

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 15 Number 2 Article 4 7-31-2006 Across Arabia with Lehi and Sariah: “Truth Shall Spring out of the Earth” Warren P. Aston Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Aston, Warren P. (2006) "Across Arabia with Lehi and Sariah: “Truth Shall Spring out of the Earth”," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 15 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol15/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title Across Arabia with Lehi and Sariah: “Truth Shall Spring out of the Earth” Author(s) Warren P. Aston Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15/2 (2006): 8–25, 110–13. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract Aston draws on his own research in Yemen and Oman as well as on the work of other scholars and research- ers to explore two locations in the Book of Mormon account of Lehi’s journey through Arabia: Nahom and Bountiful. Preliminarily, Aston highlights Nephi’s own directional indications for each leg of the jour- ney, considers the relevance of existing trade routes, and suggests relative durations of stops along the way. He reviews the research on the tribal area associ- ated with Nahom, including the discovery of an altar dating to roughly 600 bc that bears the tribal name NHM—possibly the first archaeological evidence of the Book of Mormon’s authenticity. -

The Name Mormon in Reformed Egyptian, Sumerian, and Mesoamerican Languages

The Name Mormon in reformed Egyptian, Sumerian, and Mesoamerican Languages by Jerry D. Grover Jr., PE, PG May 1, 2017 Blind third party peer review performed by After obtaining the golden plates, Joseph Smith stated that once he moved to Harmony, Pennsylvania, in the winter of 1827, he “commenced copying the characters of[f] the plates.” He stated: I copyed a considerable number of them and by means of the Urim and Thummin I translated some of them.1 In the mid 1830s, Oliver Cowdery and Frederick G. Williams recorded four characters that had been copied from the plates and Joseph Smith’s translations of those characters; one set of two characters was translated together as “The Book of Mormon” and the other set of two characters was translated as “The interpreters of languages” (see figures 1 and 2). Both of these phrases can be found in the original script of the current Title Page of the Book of Mormon. It clearly includes “Book of Mormon,” mentions “interpretation,” and infers the language of the Book of Mormon. It is reasonable therefore to assume that these characters came from the Title Page. Figure 1. Book of Mormon characters copied by Oliver Cowdery, circa 1835–1836 1 Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers: Histories, Volume 1 (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 1:240. 1 Figure 2. Close-up of the Book of Mormon characters copied by Fredrick G. Williams, circa February 27, 1836 (MacKay et al. 2013, 137) 2 In a 2015 publication, I successfully translated all four of these characters from known hieratic and Demotic Egyptian glyphs.3 The name Mormon (second glyph of the first set of two) in the “reformed Egyptian” is an interesting case study. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL Or LAST) JUDGMENT

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL or LAST) JUDGMENT Beloved Father of Mercy and Justice, We Your children, offer our lives as a pure and holy sacrifice, uniting our lives and our death to the life and death of Your Son and our Savior. At the Final Judgment we will stand united with the Body of Christ, body and soul, to receive Your Son's judgment. We will face this last and definitive judgment unafraid as the Books of Works are opened to reveal the imperishable deeds of love and mercy accumulated by the Church. This is the treasure stored up for eternity which Your children offer in the name of Christ our Savior and Redeemer. Send Your Holy Spirit, Lord, to lead us in this lesson of our study on the Eight Last Things. We pray in the name of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. + + + While I was watching thrones were set in place and one most venerable took his seat. His robe was white as snow, the hair of his head as pure as wool. His throne was a blaze of flames; its wheels were a burning fire. A stream of fire poured out, issuing from his presence. A thousand thousand waited on him, ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him. The court was in session and the books lay open. Daniel 7:9-10 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; and, because he is the Son of man, has granted him power to give judgment. -

Vol. 20 Num. 2 the FARMS Review

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 20 Number 2 Article 17 2008 Vol. 20 Num. 2 The FARMS Review FARMS Review Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Review, FARMS (2008) "Vol. 20 Num. 2 The FARMS Review," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 20 : No. 2 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol20/iss2/17 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The FARMS Review The FARMS Review Editor Daniel C. Peterson Associate Editors Louis C. Midgley George L. Mitton Production Editors Don L. Brugger Larry E. Morris Cover Design Andrew D. Livingston Layout Alison Coutts Jacob D. Rawlins The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Executive Director M. Gerald Bradford Director, FARMS Paul Y. Hoskisson Director, METI Daniel C. Peterson Director, CPART Kristian Heal Director, Publications Alison Coutts The FARMS Review Volume 20 • Number 2 • 2008 ! The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Brigham Young University © 2008 Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Brigham Young University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISSN 1550-3194 To Our Readers The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholar ship encour- ages and supports re search on the Book of Mormon, the Book of Abraham, the Bible, other ancient scripture, and related subjects.