The “Devil” in Michelangelo's Last Judgment Sarah Melanie Rolfe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

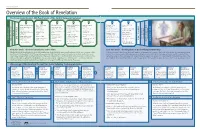

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

'Myth' and 'Religion'

THOUGHTS ON MYTH AND RELIGION IN EARLY GREEK HISTORIOGRAPHY Robert L. FOWLER University of Bristol [email protected] RESUMEN: El artículo examina el nacimiento del concepto de mythos/mito en el contexto de la historiografía y la mitografía de la Grecia arcaica. La posibilidad de oponerse a relatos tradicionales es un factor crítico en este proceso y se relaciona estrechamente con los esfuerzos de los autores por fijar su autoridad. Se compara la práctica de Heródoto con la de los primeros mitógrafos y, aunque hay amplias similitudes, hay diferencias cruciales en el tratamiento de los asuntos religiosos. Los escrúpulos personales de Heródoto responden en parte a su bien conocida reserva en lo referente a los dioses, pero es también relevante su actitud acerca de la tarea del historiador y su noción de cómo los dioses intervienen en la historia. Mientras que los mitógrafos tratan de historicizar la mitología, Heródoto trata de modo notable de desmitologizar la historia, separando ambas, pero al mismo tiempo definiendo con más profundidad que nunca sus auténticas interconexiones. Esta situación sugiere algunas consideraciones generales acerca de la relación entre mito y ritual en Grecia. ABSTRACT: The article examines the emerging concept of mythos/myth in the context of early Greek historiography and mythography. The possibility of contesting traditional stories is a critical factor in this process, and is closely related to the efforts of writers to establish their authority. Herodotos’ practice is compared with that of the early mythographers, and though there are some broad similarities, there are crucial differences in their approach to religious matters. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

1. Some of the Definitions of the Different Types of Objects in the Solar

1. Some of the definitions of the different types of objects in has the greatest orbital inclination (orbit at the the solar system overlap. Which one of the greatest angle to that of Earth)? following pairs does not overlap? That is, if an A) Mercury object can be described by one of the labels, it B) Mars cannot be described by the other. C) Jupiter A) dwarf planet and asteroid D) Pluto B) dwarf planet and Kuiper belt object C) satellite and Kuiper belt object D) meteoroid and planet 10. Of the following objects in the solar system, which one has the greatest orbital eccentricity and therefore the most elliptical orbit? 2. Which one of the following is a small solar system body? A) Mercury A) Rhea, a moon of Saturn B) Mars B) Pluto C) Earth C) Ceres (an asteroid) D) Pluto D) Mathilde (an asteroid) 11. What is the largest moon of the dwarf planet Pluto 3. Which of the following objects was discovered in the called? twentieth century? A) Chiron A) Pluto B) Callisto B) Uranus C) Charon C) Neptune D) Triton D) Ceres 12. If you were standing on Pluto, how often would you see 4. Pluto was discovered in the satellite Charon rise above the horizon each A) 1930. day? B) 1846. A) once each 6-hour day as Pluto rotates on its axis C) 1609. B) twice each 6-hour day because Charon is in a retrograde D) 1781. orbit C) once every 2 days because Charon orbits in the same direction Pluto rotates but more slowly 5. -

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL Or LAST) JUDGMENT

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL or LAST) JUDGMENT Beloved Father of Mercy and Justice, We Your children, offer our lives as a pure and holy sacrifice, uniting our lives and our death to the life and death of Your Son and our Savior. At the Final Judgment we will stand united with the Body of Christ, body and soul, to receive Your Son's judgment. We will face this last and definitive judgment unafraid as the Books of Works are opened to reveal the imperishable deeds of love and mercy accumulated by the Church. This is the treasure stored up for eternity which Your children offer in the name of Christ our Savior and Redeemer. Send Your Holy Spirit, Lord, to lead us in this lesson of our study on the Eight Last Things. We pray in the name of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. + + + While I was watching thrones were set in place and one most venerable took his seat. His robe was white as snow, the hair of his head as pure as wool. His throne was a blaze of flames; its wheels were a burning fire. A stream of fire poured out, issuing from his presence. A thousand thousand waited on him, ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him. The court was in session and the books lay open. Daniel 7:9-10 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; and, because he is the Son of man, has granted him power to give judgment. -

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou

Bacchylides 17: Singing and Usurping the Paean Maria Pavlou ACCHYLIDES 17, a Cean commission performed on Delos, has been the subject of extensive study and is Bmuch admired for its narrative artistry, elegance, and excellence. The ode was classified as a dithyramb by the Alex- andrians, but the Du-Stil address to Apollo in the closing lines renders this classification problematic and has rather baffled scholars. The solution to the thorny issue of the ode’s generic taxonomy is not yet conclusive, and the dilemma paean/ dithyramb is still alive.1 In fact, scholars now are more inclined to place the poem somewhere in the middle, on the premise that in antiquity the boundaries between dithyramb and paean were not so clear-cut as we tend to believe.2 Even though I am 1 Paean: R. Merkelbach, “Der Theseus des Bakchylides,” ZPE 12 (1973) 56–62; L. Käppel, Paian: Studien zur Geschichte einer Gattung (Berlin 1992) 156– 158, 184–189; H. Maehler, Die Lieder des Bakchylides II (Leiden 1997) 167– 168, and Bacchylides. A Selection (Cambridge 2004) 172–173; I. Rutherford, Pindar’s Paeans (Oxford 2001) 35–36, 73. Dithyramb: D. Gerber, “The Gifts of Aphrodite (Bacchylides 17.10),” Phoenix 19 (1965) 212–213; G. Pieper, “The Conflict of Character in Bacchylides 17,” TAPA 103 (1972) 393–404. D. Schmidt, “Bacchylides 17: Paean or Dithyramb?” Hermes 118 (1990) 18– 31, at 28–29, proposes that Ode 17 was actually an hyporcheme. 2 B. Zimmermann, Dithyrambos: Geschichte einer Gattung (Hypomnemata 98 [1992]) 91–93, argues that Ode 17 was a dithyramb for Apollo; see also C. -

Amillennialism Reconsidered Beatrices

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1,185-210. Copyright 0 2005 Andrews University Press. AMILLENNIALISM RECONSIDERED BEATRICES. NEALL Union College Lincoln, Nebraska Introduction G. K. Beale's latest commentary on Revelation and Kim Riddlebarger's new book A Casefor Ami~~ennialismhave renewed interest in the debate on the nature of the millennium.' Amillennialism has an illustrious history of support from Augustine, theologians of the Calvinistic and ~utheran confessions, and a long line of Reformed theologians such as Abraham Kuyper, Amin Vos, H. Ridderbos, A. A. Hoekema, and M. G. line? Amillennialists recognize that a straightforward reading of the text seems to show "the chronologicalp'ogression of Rev 19-20, the futurity of Satan's imprisonment,the physicality of 'the first resurrection' and the literalness of the one thousand years" (emphasis supplied).) However, they do not accept a chronologicalprogression of the events in these chapters, preferring instead to understand the events as recapitulatory. Their rejection of the natural reading of the text is driven by a hermeneutic of strong inaugurated eschatology4-the paradox that in the Apocalypse divine victory over the dragon and the reign of Christ and his church over this present evil world consist in participating with Christ in his sufferings and death? Inaugurated eschatology emphasizes Jesus' victory over the powers of evil at the cross. Since that monumental event, described so dramatically in Rev 12, Satan has been bound and the saints have been reigning (Rev 20). From the strong connection between the two chapters (see Table 1 below) they infer that Rev 20 recapitulates Rev 12. -

Myth, Ritual, and the Labyrinth of King Minos

Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 1 4-2015 Myth, Ritual, and the Labyrinth of King Minos Nicole Tessmer St. Louis University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/aujh Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Tessmer, Nicole (2015) "Myth, Ritual, and the Labyrinth of King Minos," Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.20429/aujh.2015.050101 Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/aujh/vol5/iss1/1 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tessmer: Myth, Ritual, and the Labyrinth of King Minos Myth, Ritual, and the Labyrinth of King Minos Nicole Tessmer St. Louis University According to ancient mythology, King Minos built a perplexing labyrinth to house the Minotaur, a monstrous creature to which his wife had given birth. Each year, the myth states, seven girls and seven boys were chosen to enter the labyrinth as tributes to become food for the Minotaur.1 It was not until Theseus entered the labyrinth, and killed the Minotaur that it could be considered a place to leave your childhood behind. Once inside, they wrestled with their demons, experienced a rebirth, and finally, emerged as adults ready to take their places in society. The myth of the labyrinth can thus be understood as a rite of passage or a coming of age ritual in ancient Greece. -

Greek Mythology #23: DIONYSUS by Joy Journeay

Western Regional Button Association is pleased to share our educational articles with the button collecting community. This article appeared in the August 2017 WRBA Territorial News. Enjoy! WRBA gladly offers our articles for reprint, as long as credit is given to WRBA as the source, and the author. Please join WRBA! Go to www.WRBA.us Greek Mythology #23: DIONYSUS by Joy Journeay God of: Grape Harvest, Winemaking, Wine, Ritual Madness, Religious Ecstasy, Fertility and Theatre Home: MOUNT OLYMPUS Symbols: Thyrus, grapevine, leopard skin Parents: Zeus and Semele Consorts: Adriane Siblings: Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces Roman Counterpart: Bacchus, Liber Dionysus’ mother was mortal Semele, daughter of a king of Thebes, and his father was Zeus, king of the gods. Dionysus was the only Olympian god to have a mortal parent. He was the god of fertility, wine and the arts. His nature reflected the duality of wine: he gave joy and divine ecstasy, or brutal and blinding rage. He and his followers could not be contained by bonds. One would imagine that being the god of “good times” could be a pretty easy and happy existence. Unfortunately, this just doesn’t happen in the world of Greek mythology. Dionysus is called “twice born.” His mother, Semele, was seduced by a Greek god, but Semele did not know which god was her lover. Fully aware of her husband’s infidelity, the jealous Hera went to Semele in disguise and convinced her to see her god lover in his true form. -

Interpretation: a Journal of Political Philosophy

Interpretation A JOURNAL A OF POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Spring 1994 Volume 21 Number 3 Aristophanes' Mark Kremer Criticism of Egalitarianism: An Interpretation of The Assembly of Women Steven Forde The Comic Poet, the City, and the Gods: Dionysus' Katabasis in the Frogs of Aristophanes Tucker Landy Virtue, Art, and the Good Life in Plato's Protagoras Nalin Ranasinghe Deceit, Desire, and the Dialectic: Plato's Republic Revisited Olivia Delgado de Torres Reflections on Patriarchy and the Rebellion of Daughters in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice and Othello Alfred Mollin On Hamlet's Mousetrap Joseph Alulis The Education of the Prince in Shakespeare's King Lear David Lowenthal King Lear Glenn W. Olsen John Rawls and the Flight from Authority: The Quest for Equality as an Exercise in Primitivism Book Reviews Will Morrisey The Roots of Political Philosophy: Ten Forgotten Socratic Dialogues, edited by Thomas L. Pangle John C. Koritansky Interpreting Tocqueville s "Democracy in America," edited by Ken Masugi Interpretation Editor-in-Chief Hilail Gildin, Dept. of Philosophy, Queens College Executive Editor Leonard Grey General Editors Seth G. Benardete Charles E. Butterworth Hilail Gildin Robert Horwitz (d. 1987) Howard B. White (d. 1974) Consulting Editors Christopher Bruell Joseph Cropsey Ernest L. Fortin John Hallowell (d. 1992) Harry V. Jaffa David Lowenthal Muhsin Mahdi Harvey C. Mansfield, Jr. Arnaldo Momigliano (d. 1987) Michael Oakeshott (d. 1990) Ellis Sandoz Leo Strauss (d. 1973) Kenneth W. Thompson European Editors Terence E. Marshall Heinrich Meier Editors Wayne Ambler Maurice Auerbach Fred Baumann Michael Blaustein Patrick Coby Edward J. Erler Maureen Feder-Marcus Joseph E. Goldberg Stephen Harvey Pamela K. -

Underworld Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2018 Underworld Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. 2019. "Underworld." In Oxford Classical Dictionary. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/123 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Underworld Radcliffe G. Edmonds III In Oxford Classical Dictionary, in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. (Oxford University Press. April 2019). http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8062 Summary Depictions of the underworld, in ancient Greek and Roman textual and visual sources, differ significantly from source to source, but they all draw on a common pool of traditional mythic motifs. These motifs, such as the realm of Hades and its denizens, the rivers of the underworld, the paradise of the blessed dead, and the places of punishment for the wicked, are developed and transformed through all their uses throughout the ages, depending upon the aims of the author or artist depicting the underworld. Some sources explore the relation of the world of the living to that of the dead through descriptions of the location of the underworld and the difficulties of entering it. By contrast, discussions of the regions within the underworld and existence therein often relate to ideas of afterlife as a continuation of or compensation for life in the world above. -

Rituals of Death and Dying in Modern and Ancient Greece

Rituals of Death and Dying in Modern and Ancient Greece Rituals of Death and Dying in Modern and Ancient Greece: Writing History from a Female Perspective By Evy Johanne Håland Rituals of Death and Dying in Modern and Ancient Greece: Writing History from a Female Perspective, by Evy Johanne Håland This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Evy Johanne Håland All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6127-8, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6127-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... viii A Note on Transliteration ......................................................................... xiii Acknowledgements ................................................................................... xv Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 6 Death Rituals and the Cult of the Dead in Greece From death in general to Greek women and death in particular