Analyzing Two Domains of Dionysus in Greek Polytheism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demeter and Dionysos: Connections in Literature, Cult and Iconography Kathryn Cook April 2011

Demeter and Dionysos: Connections in Literature, Cult and Iconography Kathryn Cook April 2011 Demeter and Dionysos are two gods among the Greek pantheon who are not often paired up by modern scholars; however, evidence from a number of sources alluding to myth, cult and iconography shows that there are similarities and connections observable from our present point of view, that were commented upon by contemporary authors. This paper attempts to examine the similarities and connections between Demeter and Dionysos up through the Classical period. These two deities were not always entwined in myth. Early evidence of gods in the Linear B tablets mention Dionysos as the name of a deity, but Demeter’s name does not appear in the records until later. Over the centuries (up to approximately the 6th century as mentioned in this paper), Demeter and Dionysos seem to have been depicted together in cult and in literature more and more often. In particular, the figure of Iacchos in the Eleusinian cult seems to form a bridging element between the two which grew from being a personification of the procession for Demeter, into being a Dionysos figure who participated in her cult. Literature: Demeter and Dionysos have some interesting parallels in literature. To begin with, they are both rarely mentioned in the Homeric poems, compared to other gods like Hera or Athena. In the Iliad, neither Demeter nor Dionysos plays a role as a main character. Instead they are mentioned in passing, as an example or as an element of an epic simile.1 These two divine figures are present even less often in the Odyssey, though this is perhaps a reflection of the fewer appearances of the gods overall, they are 1 Demeter: 2.696. -

Zeus *God of the Sky and Ruler of the Olympian Gods. He Is Lord of the Sky, the Rain God

Greek Mythology *Myths - Traditional stories about god and heroes. *The Greek people believed in many gods and goddesses. They were thought to have affected people's lives and also thought to shape events. *The gods and goddesses were thought to control nature. Some examples of the control over nature are: Zeus ruled the sky and threw lighting bolts, Demeter made the crops grow, and Poseidon caused earthquakes. *The 12 most important gods and goddesses lived on Mt. Olympus. Mt. Olympus was the highest mountain in Greece. Zeus *God of the Sky and Ruler of the Olympian gods. He is lord of the sky, the rain god. *He is represented as the god of justice and mercy, the protector of the weak, and the punisher of the wicked. Poseidon *God of the sea and protector of all the water. *Widely worshiped by seamen. *His weapon is a trident, which can shake the earth, and shatter any object. *He is second only to Zeus in power amongst the gods. *He was greedy. He had a series of disputes with other gods when he tried to take over their cities. Hades *Hades is the god of the undedrworld and ruler of the dead. *He is also the god of wealth, due to the precious metals mined from the earth. *He is a greedy god who is greatly concerned with increasing his subjects. Hestia *She plays no part in myths. *She is the Goddess of the Hearth, the symbol of the house around which a new born child is carried before it is received into the family. -

The Dialect of Elis and Its Position Within the Greek Dialectological System MA-Thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations

The dialect of Elis and its position within the Greek dialectological system MA-thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations Le site antique d’Olympie, illustration taken from Minon 2007 : 559 by M.J. van der Velden BA supervisors: dr. L. van Beek dr. A. Rademaker 2015-17 Universiteit Leiden Table of contents i. Acknowledgements ii. List of abbreviations 0. Introduction 1. The dialect features of Elean 1.1 West Greek features 1.1.1 West Greek phonological features 1.1.2 West Greek morphological features 1.1.3 Conclusion 1.2 Northwest Greek features 1.2.1 Northwest Greek phonological features 1.2.2 Northwest Greek morphological features 1.2.3 Conclusion 1.3 Features in common with various other dialects 1.3.1 Phonological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.2 Morphological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.3 Conclusion 1.4 Specifically Elean features 1.4.1 Specifically Elean phonological features 1.4.2 Specifically Elean morphological features 1.4.3 Conclusion 1.5 General conclusion 2. Evaluation 2.1 The consonant stem accusative plural in -ες 2.2 The consonant stem dative plural endings -οις and -εσσι 2.3 The middle participle in /-ēmenos/ 2.4 The development *ē > ǟ 2.5 The development *ӗ > α 2.6 The development *i > ε 3. Conclusion 4. Bibliography 2 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude towards Lucien van Beek for supervising my work, without whose help, comments and – at times necessary – incitations this study would not have reached its current shape, as well as towards Adriaan Rademaker for carefully reading my work and sharing his remarks. -

Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza's Ethics

Midwest Studies in Philosophy, XXVI (2002) Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza’s Ethics STEVEN NADLER I Descartes famously prided himself on the felicitous consequences of his philoso- phy for religion. In particular, he believed that by so separating the mind from the corruptible body, his radical substance dualism offered the best possible defense of and explanation for the immortality of the soul. “Our natural knowledge tells us that the mind is distinct from the body, and that it is a substance...And this entitles us to conclude that the mind, insofar as it can be known by natural phi- losophy, is immortal.”1 Though he cannot with certainty rule out the possibility that God has miraculously endowed the soul with “such a nature that its duration will come to an end simultaneously with the end of the body,” nonetheless, because the soul (unlike the human body, which is merely a collection of material parts) is a substance in its own right, and is not subject to the kind of decomposition to which the body is subject, it is by its nature immortal. When the body dies, the soul—which was only temporarily united with it—is to enjoy a separate existence. By contrast, Spinoza’s views on the immortality of the soul—like his views on many issues—are, at least in the eyes of most readers, notoriously difficult to fathom. One prominent scholar, in what seems to be a cry of frustration after having wrestled with the relevant propositions in Part Five of Ethics,claims that this part of the work is an “unmitigated and seemingly unmotivated disaster.. -

'Myth' and 'Religion'

THOUGHTS ON MYTH AND RELIGION IN EARLY GREEK HISTORIOGRAPHY Robert L. FOWLER University of Bristol [email protected] RESUMEN: El artículo examina el nacimiento del concepto de mythos/mito en el contexto de la historiografía y la mitografía de la Grecia arcaica. La posibilidad de oponerse a relatos tradicionales es un factor crítico en este proceso y se relaciona estrechamente con los esfuerzos de los autores por fijar su autoridad. Se compara la práctica de Heródoto con la de los primeros mitógrafos y, aunque hay amplias similitudes, hay diferencias cruciales en el tratamiento de los asuntos religiosos. Los escrúpulos personales de Heródoto responden en parte a su bien conocida reserva en lo referente a los dioses, pero es también relevante su actitud acerca de la tarea del historiador y su noción de cómo los dioses intervienen en la historia. Mientras que los mitógrafos tratan de historicizar la mitología, Heródoto trata de modo notable de desmitologizar la historia, separando ambas, pero al mismo tiempo definiendo con más profundidad que nunca sus auténticas interconexiones. Esta situación sugiere algunas consideraciones generales acerca de la relación entre mito y ritual en Grecia. ABSTRACT: The article examines the emerging concept of mythos/myth in the context of early Greek historiography and mythography. The possibility of contesting traditional stories is a critical factor in this process, and is closely related to the efforts of writers to establish their authority. Herodotos’ practice is compared with that of the early mythographers, and though there are some broad similarities, there are crucial differences in their approach to religious matters. -

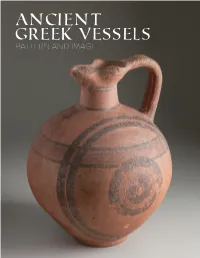

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

The Contest Between Athena and Poseidon. Myth, History and Art

ANDRÁS PATAY-HORVÁTH The Contest between Athena and Poseidon. Myth, History and Art The myth was a well-known one in antiquity, and it is well-known even to- day. There are many versions in various extant literary sources1 and even some depictions in sculpture, vase painting and minor arts2. Surprisingly enough, the famous myth has not attracted much scholarly interest3. The modern commen- taries simply list the relevant passages, but hardly attempt a thorough comparative analysis4. The present paper (an updated, revised and abbreviated version of Patay-Horváth 2002a) would like to present a study, suggesting strong intercon- nections between Athenian history and the evolution of the myth. Beside the many familiar texts and works of art, I will also introduce a new piece of evidence, which has never been considered in this context and hope that it will become ap- parent, that the role of Poseidon and the sea is much more important in this myth than has generally been acknowledged. It is appropriate to begin with a fairly detailed version of the myth from the mythological textbook of Apollodorus (Bibl. III 14). It can serve as a very practi- cal introduction to the subject because it contains not only one version but some alternatives as well. Cecrops, a son of the soil, with a body compounded of man and serpent, was the first king of Attica, and the country which was formerly called Acte he named Cecropia after himself. In his time, they say, the gods resolved to take possession of cities in which each of them should receive his own peculiar wor- ship. -

7Th Grade Lesson Plan: It's Greek to Me: Greek Mythology

7th grade Lesson Plan: It’s Greek to me: Greek Mythology Overview This series of lessons was designed to meet the needs of gifted children for extension beyond the standard curriculum with the greatest ease of use for the edu- cator. The lessons may be given to the students for individual self-guided work, or they may be taught in a classroom or a home-school setting. This particular lesson plan is primarily effective in a classroom setting. Assessment strategies and rubrics are included. The lessons were developed by Lisa Van Gemert, M.Ed.T., the Mensa Foundation’s Gifted Children Specialist. Introduction Greek mythology is not only interesting, but it is also the foundation of allusion and character genesis in literature. In this lesson plan, students will gain an understanding of Greek mythology and the Olympian gods and goddesses. Learning Objectives Materials After completing the lessons in this unit, students l D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths by Ingri and will be able to: Edgar Parin D’Aulaire l Understand the Greek view of creation. l The Gods and Goddesses of Olympus by Aliki l Understand the terms Chaos, Gaia, Uranus, Cro- l The Mighty 12: Superheroes of Greek Myths by nus, Zeus, Rhea, Hyperboreans, Ethiopia, Mediter- Charles Smith ranean, and Elysian Fields. l Greek Myths and Legends by Cheryl Evans l Describe the Greek view of the world’s geogra- l Mythology by Edith Hamilton (which served as a phy. source for this lesson plan) l Identify the names and key features of the l A paper plate for each student Olympian gods/goddesses. -

Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2009 A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. "A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' 'Orphic' Creation of Mankind." American Journal of Philology 130, no. 4 (2009): 511-532. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Radcliffe G. Edmonds III “A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' ‘Orphic’ Creation of Mankind” American Journal of Philology 130 (2009), pp. 511–532. A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' Creation of Mankind Olympiodorus' recounting (In Plat. Phaed. I.3-6) of the Titan's dismemberment of Dionysus and the subsequent creation of humankind has served for over a century as the linchpin of the reconstructions of the supposed Orphic doctrine of original sin. From Comparetti's first statement of the idea in his 1879 discussion of the gold tablets from Thurii, Olympiodorus' brief testimony has been the -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

1. Some of the Definitions of the Different Types of Objects in the Solar

1. Some of the definitions of the different types of objects in has the greatest orbital inclination (orbit at the the solar system overlap. Which one of the greatest angle to that of Earth)? following pairs does not overlap? That is, if an A) Mercury object can be described by one of the labels, it B) Mars cannot be described by the other. C) Jupiter A) dwarf planet and asteroid D) Pluto B) dwarf planet and Kuiper belt object C) satellite and Kuiper belt object D) meteoroid and planet 10. Of the following objects in the solar system, which one has the greatest orbital eccentricity and therefore the most elliptical orbit? 2. Which one of the following is a small solar system body? A) Mercury A) Rhea, a moon of Saturn B) Mars B) Pluto C) Earth C) Ceres (an asteroid) D) Pluto D) Mathilde (an asteroid) 11. What is the largest moon of the dwarf planet Pluto 3. Which of the following objects was discovered in the called? twentieth century? A) Chiron A) Pluto B) Callisto B) Uranus C) Charon C) Neptune D) Triton D) Ceres 12. If you were standing on Pluto, how often would you see 4. Pluto was discovered in the satellite Charon rise above the horizon each A) 1930. day? B) 1846. A) once each 6-hour day as Pluto rotates on its axis C) 1609. B) twice each 6-hour day because Charon is in a retrograde D) 1781. orbit C) once every 2 days because Charon orbits in the same direction Pluto rotates but more slowly 5. -

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone myth in modern fiction Janet Catherine Mary Kay Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Ancient Cultures) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Sjarlene Thom December 2006 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………… 2 THE DEMETER/PERSEPHONE MYTH IN MODERN FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction: The Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction 4 1.1 Theories for Interpreting the Myth 7 2. The Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.1 Synopsis of the Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.2 Commentary on the Demeter/Persephone Myth 16 2.3 Interpretations of the Demeter/Persephone Myth, Based on Various 27 Theories 3. A Fantasy Novel for Teenagers: Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood 38 by Meredith Ann Pierce 3.1 Brown Hannah – Winter 40 3.2 Green Hannah – Spring 54 3.3 Golden Hannah – Summer 60 3.4 Russet Hannah – Autumn 67 4. Two Modern Novels for Adults 72 4.1 The novel: Chocolat by Joanne Harris 73 4.2 The novel: House of Women by Lynn Freed 90 5. Conclusion 108 5.1 Comparative Analysis of Identified Motifs in the Myth 110 References 145 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The question that this thesis aims to examine is how the motifs of the myth of Demeter and Persephone have been perpetuated in three modern works of fiction, which are Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood by Meredith Ann Pierce, Chocolat by Joanne Harris and House of Women by Lynn Freed.