Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

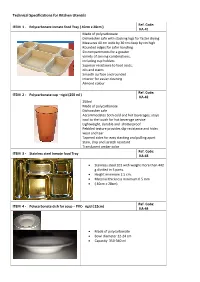

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref. -

Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter

NHBB B-Set Bowl 2017-2018 Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter (1) The remnants of this government established the Republic of Ezo after losing the Boshin War. Two and a half centuries earlier, this government was founded after its leader won the Battle of Sekigahara against the Toyotomi clan. This government's policy of sakoku came to an end when Matthew Perry's Black Ships forced the opening of Japan through the 1854 Convention of Kanagawa. For ten points, name this last Japanese shogunate. ANSWER: Tokugawa Shogunate (or Tokugawa Bakufu) (2) Xenophon's Anabasis describes ten thousand Greek soldiers of this type who fought Artaxerxes II of Persia. A war named for these people was won by Hamilcar Barca and led to his conquest of Spain. Famed soldiers of this type include slingers from Rhodes and archers from Crete. Greeks who fought for Persia were, for ten points, what type of soldier that fought not for national pride, but for money? ANSWER: mercenary (prompt on descriptive answers) (3) The most prominent of the Townshend Acts not to be repealed in 1770 was a tax levied on this commodity. The Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver carried this commodity from England to the American colonies. The Intolerable Acts were passed in response to the dumping of this commodity into a Massachusetts Harbor in 1773 by members of the Sons of Liberty. For ten points, identify this commodity destroyed in a namesake Boston party. ANSWER: tea (accept Tea Act; accept Boston Tea Party) (4) This location is the setting of a photo of a boy holding a toy hand grenade by Diane Arbus. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology Medieval Pottery Research Group Prehistoric Ceramics Research Group Study Group for Roman Pottery Draft 4 October 2015 CONTENTS Section 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Aims 1 1.2 Scope 1 1.3 Structure 2 1.4 Project Tasks 2 1.5 Using the Standard 5 Section 2 The Standard 6 2.1 Project Planning 6 2.2 Collection and Processing 8 2.3 Assessment 11 2.4 Analysis 13 2.5 Reporting 17 2.6 Archive Creation, Compilation and Transfer 20 Section 3 Glossary of Terms 23 Section 4 References 25 Section 5 Acknowledgements 27 Appendix 1 Scientific Analytical Techniques 28 Appendix 2 Approaches to Assessment 29 Appendix 3 Approaches to Analysis 33 Appendix 4 Approaches to Reporting 39 1. INTRODUCTION Pottery has two attributes that lend it great potential to inform the study of human activity in the past. The material a pot is made from, known to specialists as the fabric, consists of clay and inclusions that can be identified to locate the site at which a pot was made, as well as indicate methods of manufacture and date. The overall shape of a pot, together with the character of component parts such as rims and handles, and also the technique and style of decoration, can all be studied as the form. This can indicate when and how a pot was made and used, as well as serving to define cultural affinities. The interpretation of pottery is based on a detailed characterisation of the types present in any group, supported by sound quantification and consistent approaches to analysis that facilitate comparison between assemblages. -

Catalogue 8 Autumn 2020

catalogue 8 14-16 Davies Street london W1K 3DR telephone +44 (0)20 7493 0806 e-mail [email protected] WWW.KalloSgalleRy.com 1 | A EUROPEAN BRONZE DIRK BLADE miDDle BRonze age, ciRca 1500–1100 Bc length: 13.9 cm e short sword is thought to be of english origin. e still sharp blade is ogival in form and of rib and groove section. in its complete state the blade would have been completed by a grip, and secured to it by bronze rivets. is example still preserves one of the original rivets at the butt. is is a rare form, with wide channels and the midrib extending virtually to the tip. PRoVenance Reputedly english With H.a. cahn (1915–2002) Basel, 1970s–90s With gallery cahn, prior to 2010 Private collection, Switzerland liteRatuRe Dirks are short swords, designed to be wielded easily with one hand as a stabbing weapon. For a related but slightly earlier in date dagger or dirk with the hilt still preserved, see British museum: acc. no. 1882,0518.6, which was found in the River ames. For further discussion of the type, cf. J. evans, e Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland, london, 1881; S. gerloff and c.B. Burgess, e Dirks and Rapiers of Great Britain and Ireland, abteilung iV: Band 7, munich, Beck, 1981. 4 5 2 | TWO GREEK BRONZE PENDANT BIRD)HEAD PYXIDES PRoVenance christie’s, london, 14 may 2002, lot 153 american private collection geometRic PeRioD, ciRca 10tH–8tH centuRy Bc Heights: 9.5 cm; 8 cm liteRatuRe From northern greece, these geometric lidded pendant pyxides are called a ‘sickle’ type, one with a broad tapering globular body set on a narrow foot that flares at the base; the other and were most likely used to hold perfumed oils or precious objects. -

A Prize Aryballos

A PRIZE ARYBALLOS (PLATES 63 AND 64) T nHE most interesting single find from the excavation of 1954 on Temple Hill in Corinth was the fine aryballos of Middle Corinthian date with a representationof a dancing chorus (see above, pp. 151-152). Its significance is readily apparent: in it are combbinedneat and very careful workmanship,a fresh and lively scene, which is one of the earliest representations of a dancing chorus, and one of the longest archaic Corinthian inscriptions, other than a list of names, yet discovered on a vase (PIs. 63, 64). The subject of the scene and the inscription imply that this was not an ordin- ary product of the potter's workshop, but a special order, made as a prize, or in com- memoration of a vrictoryin a dancing contest, and dedicated by the chorus leader, Pyrvias (Pyrrhias). It is a vase worthy of a place in the early archaic temple in spite of its small size,' for every element of its decoration shows great care and the scene, with its youthful chorus and leader, is no comast dance, but a serious and proper performance, gracefully and simply executed. The vase is complete except for a piece of the front part of the lip, conveniently broken in antiquity to reveal the scene better to its modern viewers. It shows no signs of actual use, but is worn slightly on the sides and back of the handle by abrasion from the rough filling in which it lay. The clay is a typical Corinthian buff, the surface smooth and polished. -

Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta Type III S Conical, Boxer Rhyton (651)

Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta Type III S Conical, Boxer Rhyton (651). Reconstruction drawing by R. Porter (see also Fig. 29). PREHISTORY MONOGRAPHS 19 Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta by Robert B. Koehl Published by INSTAP Academic Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 2006 Design and Production INSTAP Academic Press Printing CRWGraphics, Pennsauken, New Jersey Binding Hoster Bindery, Inc., Ivyland, Pennsylvania Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Koehl, Robert B. Aegean Bronze Age rhyta / by Robert B. Koehl. p. cm. — (Prehistory monographs ; 19) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-931534-16-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Aegean Sea Region—Antiquities. 2. Rhyta—Aegean Sea Region. 3. Bronze age—Aegean Sea Region. I. Title. II. Series. DF220.K64 2006 938’.01—dc22 2006027437 Copyright © 2006 INSTAP Academic Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America In honor of my mother, Ruth and to the memory of my father, Seymour Table of Contents LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT . ix LIST OF TABLES . xi LIST OF FIGURES . xiii LIST OF PLATES . xv PREFACE . xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xxiii LIST OF DRAWING CREDITS . xxvii LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS . xxix ABBREVIATIONS AND CONVENTIONS . xxxi INTRODUCTION . 1 1. TYPOLOGY, HISTORY, AND DEVELOPMENT . 5 Principle of Typology and Definition of Types . 5 Definition of Classes and Their Nomenclature . 7 Rhyton Groups: Typology of Rims, Handles, and Bases . 7 Exclusions and Exceptions . 9 Organization and Presentation . 12 Aegean Rhyta . 13 Type I . 13 Type II . 21 Type III . 38 Type IV . 53 Type Indeterminate . 64 Foreign Imitations of Aegean Rhyta . 64 viii AEGEAN BRONZE AGE RHYTA 2. -

Analyzing Two Domains of Dionysus in Greek Polytheism

Philomathes Two Sides of the Dice: Analyzing Two Domains of Dionysus in Greek Polytheism T he study of religion in ancient Greece is complicated by the fact that, unlike modern world religions with ancient roots, there is no “holy doctrine” to which scholars can refer. Although they shared a complex pantheon of gods, ancient Greek city- states were never a unified political empire; instead of a globalized dogma, religion was localized within each polis, whose inhabitants developed their own unique variations on “Greek” religious rituals and beliefs.1 The multiplex natures of ancient Greek gods compounds the problem; it is a monumental task to study all aspects of all deities in the Greek world. As a result, scholarship often focuses solely on a single popular aspect or well-known cult of a god or goddess — such as Apollo Pythios of Delphi or Athena Parthenos of Athens, neglecting other facets of the gods’ cult and personality.2 Greek religion, 1 As Jon D. Mikalson states in Athenian Popular Religion (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1983), 4, “In varying degrees Sparta, Corinth, Thebes, Athens and the other city-states differed from one another in political, social, and economic structure, and it is only reasonable to assume that they also differed in some extent in their religion … One should be wary of assuming that a religious belief or practice must have been current in all the city-states and among all Greek simply because it is attested for one city-state.” 2 Apollo is generally remembered as the god of prophecy because of his oracle and cult in Delphi. -

Perfume Vessels in South-East Italy

Perfume Vessels in South-East Italy A Comparative Analysis of Perfume Vessels in Greek and Indigenous Italian Burials from the 6th to 4th Centuries B.C. Amanda McManis Department of Archaeology Faculty of Arts University of Sydney October 2013 2 Abstract To date there has been a broad range of research investigating both perfume use in the Mediterranean and the cultural development of south-east Italy. The use of perfume was clearly an important practice in the broader Mediterranean, however very little is known about its introduction to the indigenous Italians and its subsequent use. There has also been considerable theorising about the nature of the cross-cultural relationship between the Greeks and the indigenous Italians, but there is a need for archaeological studies to substantiate or refute these theories. This thesis therefore aims to make a relevant contribution through a synthesis of these areas of study by producing a preliminary investigation of the use of perfume vessels in south-east Italy. The assimilation of perfume use into indigenous Italian culture was a result of their contact with the Greek settlers in south-east Italy, however the ways in which perfume vessels were incorporated into indigenous Italian use have not been systematically studied. This thesis will examine the use of perfume vessels in indigenous Italian burials in the regions of Peucetia and Messapia and compare this use with that of the burials at the nearby Greek settlement of Metaponto. The material studied will consist of burials from the sixth to fourth centuries B.C., to enable an analysis of perfume use and social change over time. -

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts Battle of the Greeks and Amazons Temple of Apollo at Phigaleia (Bassai) Greek, late 5th c. B.C. The Mausoleion at Halikarnassos Greek, ca. 360-340 B.C. Myth: The Amazons lived in the northern limits of the known world. They were warrior women who fought from horseback usually with bow and arrows, but also with axe and spear. Their shields were crescent shaped. They destroyed the right breast of young Amazons, to facilitate use of the bow. The Attic hero Theseus had joined Herakles on his expedition against them and received the Amazon Antiope (or Hippolyta) as his share of the spoils of war. In revenge, the Amazons invaded Attica. In the subsequent battle Antiope was killed. This battle was represented in a number of works, notably the metopes of the Parthenon and the shield of the Athena Parthenos, the great cult statue by Pheidias that stood in the Parthenon. Symbolically, the battle represents the triumph of civilization over barbarism. Battle of the Gods and Giants Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon (Zeus battling Giants) Greek, ca. 180 B.C. Myth: The giants, born of Earth, threatened Zeus and the other gods, and a fierce struggle ensued, the so-called Gigantomachy, or battle of the gods and giants. The giants were defeated and imprisoned below the earth. This section of the frieze from the altar shows Zeus battling three giants. The myth may reflect an event of prehistory, the arrival ca. 2000 B.C. of Greek- speaking invaders, who brought with them their own gods, whose chief god was Zeus. -

A Quick Start Guide to the Art of Drinking

A QUICK START GUIDE TO THE ART OF DRINKING • Bacchus, the god of wine, has four common cult titles: Bromius, Iacchus, Lenaeus, and Lyaeus. Obsopoeus uses them all, and each can be a poetic word for wine; hence “worshipping Bacchus” can also mean to literally drink wine. • The most famous wine of antiquity was Falernian. Like champagne, its name comes from the region it was produced in, and like “champagne,” Obso- poeus uses it as a general word for wine. • Greeks and Romans had scads of different vessels for storing, preparing, serving, and drinking wine. Obsopoeus sometimes uses their names in their original sense and sometimes for analogous vessels of his own time. The illustration and chart on the following pages show which are which. xxix A QUICK START GUIDE Greek Latin Modern equivalent STORAGE pithos dolium barrel amphora cadus bottle PREPARATION krater crater N/A (a bowl for mingling water and wine) N/A obba decanter SERVING kyathos cyathus a drink or “round” of drinks (a ladle) N/A trulla a drink or “round” of drinks (a dipping cup) N/A capedo pitcher or carafe DRINKING kylix calix wineglass (Italian calice, English chalice) kantharos cantharus trophy cup skyphos scyphus bowl phiale patera saucer or wineglass karchesion carchesium stein or mug The Latin word poculum (cup) denotes any of these drinking vessels, but, like the serving vessels, it is usually used metaphori- cally for “a drink” or “a round” (as in the phrase inter pocula, “over drinks”). xxx Greek and Roman wine vessels, in Obsopoeus’ Latin spelling. For their use and Greek spelling, see the table. -

Tableware Fiber Blend

www.earthchoicepackaging.com Tableware Fiber Blend Social responsibility, respect and care for the environment require action in today’s world, while keeping an eye on the future. These products are made from trees and other renewable plant-based materials. Fiber (paper) material Soak through resistant design • Made of a blend of bagasse (sugar cane), • Resists grease, moisture and helps bamboo and wood fibers, which are eliminate messy leaks renewable resources. Compostable Strong • Many SKUs meet ASTM D6868 • Offers durable construction for multi-food compostability standard and are applications compostable in commercial facilities, which may not exist in all areas. Not suitable for home composting. www.earthchoicepackaging.com Tableware Pactiv Item MC500120001 Pactiv Item MC500160001 Pactiv Item MC500060001 Pactiv Item MC500070001 ® 6.75” Placesetter® 12 oz. Placesetter® 16 oz. Placesetter® 6” Placesetter Description Description Description Preferred™ Snack Description Preferred™ Snack Preferred™ Bowl Preferred™ Bowl Plate Plate Case Cube 2.1 Case Cube 2.73 Case Cube 1.3 Case Cube 2.1 Case Wt. 23.5 Case Wt. 27.9 Case Wt. 16.7 Case Wt. 20.2 Case Pack 1000 Case Pack 1000 Case Pack 1000 Case Pack 1000 Pactiv Item YMC500090002 Pactiv Item YMC500110002 Pactiv Item MC500440002 Pactiv Item MC500100002 ® 8.75” Placesetter® 10” Placesetter® ® 8.75” Placesetter ™ 10” Placesetter Description ™ Description Preferred Description Preferred Description Preferred Plate 3-Cmpt. Platel 3-Cmpt. Plate Preferred Plate Case Cube 1.34 Case Cube 1.23 Case Cube 2.5 Case Cube 1.3 Case Wt. 18.0 Case Wt. 18.0 Case Wt. 24.6 Case Wt. 24.64 Case Pack 500 Case Pack 500 Case Pack 500 Case Pack 500 Pactiv Item MC500430001 Pactiv Item YMC500470001 Pactiv Item MF500100000 Pactiv Item MF500440000 7.5” x 10” 9.875” x 12.5” EarthChoice 10” EarthChoice 10”/3 Placesetter® Placesetter® Description Description cmpt fiber plate Description Preferred Oval Description Preferred Oval fiber plate USA USA Platter Platter Case Cube 1.8 Case Cube 2.5 Case Cube 1.3 Case Cube 2.30 Case Wt.