Kerch Vases in the Black Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

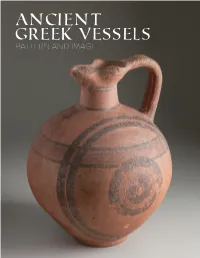

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

Diachronic Land Uses Changes in Semi Mountainous Areas Next to Urban and Tourist Areas

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-4 Issue-10, March 2015 Diachronic Land Uses Changes in Semi Mountainous Areas Next to Urban and Tourist Areas Vasileios C. Drosos, Anastasia Stergiadou, Vasileios J. Giannoulas, George Doukas Abstract— Land cover data documents how much of a region A timely and accurate change detection of various distinctive is covered by forests, wetlands, impervious surfaces, agriculture, features on the surface of the Earth is extremely important for and other land and water types. Water types include wetlands or understanding the relationships and interactions between open water. Land use shows how people use the landscape – human and natural phenomena to manage and better utilize whether for development, conservation, or mixed uses. The of natural resources [12]. Land use, land-use change and relationship between the land ownership status and the rate of forestry (LULUCF) is defined by the United Nations Climate coverage by trees or shrubs do the unconscious people to put fires. The timeless control of changes and land use maps prevent Change Secretariat as “A greenhouse gas inventory sector fires aimed at creating plots. In the context of this research, land that covers emissions and removals of greenhouse gases cover maps of previous years and recent ones were compared, resulting from direct human-induced land use, land-use with the help of aerial photographs and analytical and digital change and forestry activities” [7]. photogrammetric stations in representative regions of Greece. The Greek landscape, as in all Mediterranean countries, Generally we observe that where intense coastal tourist traffic has undergone a significant change. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

Walking Tour in Sithonia

WALKING TOUR IN SITHONIA DAY 1: Neos Marmaras Arrival and transfer to the hotel. Dinner and accommodation in Neos Marmaras. DAY 2: Neos Marmaras - Parthenonas On our first long walk, we will visit the very old village of Parthenonas. The walker is given two alternative methods of ascent and descent, depending on one’s abilities. We will take a beautiful but strenuous route, which visits an old water mill and dam and then climbs straight up a ridge, through olive groves and forest, to reach high forest tracks leading to the village. The village, Parthenonas, goes back to the days of pirates, when the locals sought a high vantage point to protect them from danger. In addition, it is well known that Parthenonas town has nice taverns that anyone can enjoy. Overnight in Neos Marmaras. DAY 3: Porto Koufo – Kapros This easy walk starts at the beautiful natural harbor of Porto Koufo on the west coast of Sithonia. We will see the majestic harbour of Porto Koufo, which is more like a fjord. The route uses farm and goat tracks to reach Karpos the remote southern peak of the peninsula. The path passes through an area rich in flora and fauna. Fine views can be obtained from Kapros off the precipitous cliffs along the coast. On our first path we will visit Marathias beach. On a fine day the Sporades Islands can be seen to the southwest. The return route follows the edge of the field eventually leading on to an old path which rises through olive groves to a pavilion with bench seat overlooking the harbor to the north. -

A Collection of Exceptional Ancient Greek Coins

A Collection of Exceptional Ancient Greek Coins To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Book Room 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Monday 24 October 2011 at 11.00 am Public viewing: Morton & Eden, 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Thursday 20 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Friday 21 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Sunday 23 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 51 Price £15 Enquiries: Tom Eden or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 160 (front); Lot 166 (back); Lot 126 (inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding Morton & Eden Ltd offer an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the understanding that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connection. -

The Bosporan Army” and “The Army on the Bosporus” in the Time of Mithradates Vi Eupator, King of Pontus

Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae, 2014, 27, s. 11-19 FASCICULI ARCHAEOLOGIAE HISTORICAE FASC. XXVII, PL ISSN 0860-0007 MARIUSZ MIELCZAREK “THE BOSPORAN ARMY” AND “THE ARMY ON THE BOSPORUS” IN THE TIME OF MITHRADATES VI EUPATOR, KING OF PONTUS Abstract: During the reign of Mithradates VI Eupator, king of Pontus, the Cimmerian Bosporus was incorporated to the kingdom of Pontus. Detachments of the Mithradatic army were located on the Bosporus. The military forces of which the Bosporans disposed of also stayed on the Bosporus. The organization of the military forces as well as soldiers’ arms and armour are discussed. Special attention is devoted to the epigraphic material which is evidently the most important piece of evidence relating to the military history of the Bosporus of Mithradatic times. Keywords: Bosporus, Mithradates VI Eupator, army, arms and armour About 107 BCE Bosporan Kingdom (map 1) lost its inde- which took place during the first Mithradatic war against pendence1. The Bosporus had come under the rule of Mithra- Rome and just after, indicates that after subjugation to dates VI Eupator, king of Pontus2 (Fig. 1). Units of Mithra- Mithradates, significant military forces stayed in disposi- dates’3 army were located in the Bosporan centers 4, as had been tion of the Bosporans7. Appian wrote that a strong fleet and done in other north Pontic cities5 incorporated into Mithra- numerous Pontic forces were ordered against Bosporus8. dates’ sphere of interest at the end of the second century BCE. On the other hand Appian’s account is very interesting, as Appian’s passage about the “rebellion” of the Bosporans6, the economic9 situation of the Bosporus was far from being prosperous before its incorporation to Mithradates VI’s possessions. -

"The Greeks in the History of the Black Sea" Report

DGIV/EDU/HIST (2000) 01 Activities for the Development and Consolidation of Democratic Stability (ADACS) Meeting of Experts on "The Greeks in the History of the Black Sea" Thessaloniki, Greece, 2-4December 1999 Report Strasbourg Meeting of Experts on "The Greeks in the History of the Black Sea" Thessaloniki, Greece, 2-4December 1999 Report The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 5 Introductory remarks by James WIMBERLEY, Head of the Technical Cooperation and Assistance Section, Directorate of Education and Higher Education.................................................................................................................... 6 PRESENTATIONS -Dr Zofia Halina ARCHIBALD........................................................................11 -Dr Emmanuele CURTI ....................................................................................14 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Dr Constantinos CHATZOPOULOS..........................................................................17 APPENDIX I LIST OF PARTICIPANTS.........................................................................................21 APPENDIX II PROGRAMME OF THE SEMINAR.........................................................................26 APPENDIX III INTRODUCTORY PRESENTATION BY PROFESSOR ARTEMIS XANTHOPOULOU-KYRIAKOU.............................................................................30 -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

Catalogue 8 Autumn 2020

catalogue 8 14-16 Davies Street london W1K 3DR telephone +44 (0)20 7493 0806 e-mail [email protected] WWW.KalloSgalleRy.com 1 | A EUROPEAN BRONZE DIRK BLADE miDDle BRonze age, ciRca 1500–1100 Bc length: 13.9 cm e short sword is thought to be of english origin. e still sharp blade is ogival in form and of rib and groove section. in its complete state the blade would have been completed by a grip, and secured to it by bronze rivets. is example still preserves one of the original rivets at the butt. is is a rare form, with wide channels and the midrib extending virtually to the tip. PRoVenance Reputedly english With H.a. cahn (1915–2002) Basel, 1970s–90s With gallery cahn, prior to 2010 Private collection, Switzerland liteRatuRe Dirks are short swords, designed to be wielded easily with one hand as a stabbing weapon. For a related but slightly earlier in date dagger or dirk with the hilt still preserved, see British museum: acc. no. 1882,0518.6, which was found in the River ames. For further discussion of the type, cf. J. evans, e Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland, london, 1881; S. gerloff and c.B. Burgess, e Dirks and Rapiers of Great Britain and Ireland, abteilung iV: Band 7, munich, Beck, 1981. 4 5 2 | TWO GREEK BRONZE PENDANT BIRD)HEAD PYXIDES PRoVenance christie’s, london, 14 may 2002, lot 153 american private collection geometRic PeRioD, ciRca 10tH–8tH centuRy Bc Heights: 9.5 cm; 8 cm liteRatuRe From northern greece, these geometric lidded pendant pyxides are called a ‘sickle’ type, one with a broad tapering globular body set on a narrow foot that flares at the base; the other and were most likely used to hold perfumed oils or precious objects.