Perfume Vessels in South-East Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

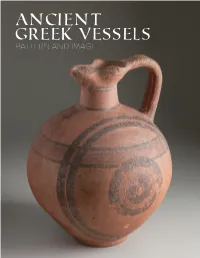

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

An Osteobiography of Roman Burial from Oğlanqala, Azerbaijan

Death on the Imperial Frontier: an Osteobiography of Roman Burial from Oğlanqala, Azerbaijan THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Selin Elizabeth Nugent, B.S. Graduate Program in Anthropology The Ohio State University 2013 Master’s Examination Committee: Clark S. Larsen, Advisor Mark Hubbe Samuel Stout Barbara Piperata Copyrighted by Selin Elizabeth Nugent 2013 Abstract In 2011, excavations at the Iron Age archaeological site of Oğlanqala in Naxçivan, Azerbaijan uncovered unexpected human remains dating to the early Roman period (2 B.C. - c. 14 A.D.). At Oğlanqala, numerous post-Iron Age interments from the early 20th century have been recovered. However, the early Roman burial represents the only Roman interment discovered at the site as well as in the South Caucasus. Burial WWE.1 was situated at the base of the Oğlanqala Iron Age citadel and consisted of a single individual (Individual 21) placed in a seated position inside a large pithos, or urn. While urn burial is a common practice in the Caucasus, the individual was accompanied by a large quantity of fine Roman material objects rarely found in this region, including Augustan denarii, glass unguentaria, gold inlayed intaglio rings on the fingers, a ceramic round bottom vessel, and a large glass bead. This paper presents a detailed analysis of the bioarchaeological identity of Individual 21, focusing on age, stress, status, and mobility and how these factors relate to the unusual burial style. Osteological and oxygen (18O /16O) stable isotope analysis, archaeological context of the burial, and the historical record provide the basis to identify the individual. -

Herakles Iconography on Tyrrhenian Amphorae

HERAKLES ICONOGRAPHY ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________________________________________ by MEGAN LYNNE THOMSEN Dr. Susan Langdon, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Susan Langdon, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Marcus Rautman and Dr. David Schenker, for their help during this process. Also, thanks must be given to my family and friends who were a constant support and listening ear this past year. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE—A BRIEF STUDY…..……………………....1 Early Studies Characteristics of Decoration on Tyrrhenian Amphorae Attribution Studies: Identifying Painters and Workshops Market Considerations Recent Scholarship The Present Study 2. HERAKLES ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE………………………….…30 Herakles in Vase-Painting Herakles and the Amazons Herakles, Nessos and Deianeira Other Myths of Herakles Etruscan Imitators and Contemporary Vase-Painting 3. HERAKLES AND THE FUNERARY CONTEXT………………………..…48 Herakles in Etruria Etruscan Concepts of Death and the Underworld Etruscan Funerary Banquets and Games 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………..67 iii APPENDIX: Herakles Myths on Tyrrhenian Amphorae……………………………...…72 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..77 ILLUSTRATIONS………………………………………………………………………82 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Tyrrhenian Amphora by Guglielmi Painter. Bloomington, IUAM 73.6. Herakles fights Nessos (Side A), Four youths on horseback (Side B). Photos taken by Megan Thomsen 82 2. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310039) by Fallow Deer Painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen 1428. Photo CVA, MUNICH, MUSEUM ANTIKER KLEINKUNST 7, PL. 322.3 83 3. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310045) by Timiades Painter (name vase). -

The First Illyrian War: a Study in Roman Imperialism

The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism Catherine A. McPherson Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal February, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Catherine A. McPherson, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………….……………............2 Abrégé……………………………………...………….……………………3 Acknowledgements………………………………….……………………...4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One Sources and Approaches………………………………….………………...9 Chapter Two Illyria and the Illyrians ……………………………………………………25 Chapter Three North-Western Greece in the Later Third Century………………………..41 Chapter Four Rome and the Outbreak of War…………………………………..……….51 Chapter Five The Conclusion of the First Illyrian War……………….…………………77 Conclusion …………………………………………………...…….……102 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..104 2 Abstract This paper presents a detailed case study in early Roman imperialism in the Greek East: the First Illyrian War (229/8 B.C.), Rome’s first military engagement across the Adriatic. It places Roman decision-making and action within its proper context by emphasizing the role that Greek polities and Illyrian tribes played in both the outbreak and conclusion of the war. It argues that the primary motivation behind the Roman decision to declare war against the Ardiaei in 229 was to secure the very profitable trade routes linking Brundisium to the eastern shore of the Adriatic. It was in fact the failure of the major Greek powers to limit Ardiaean piracy that led directly to Roman intervention. In the earliest phase of trans-Adriatic engagement Rome was essentially uninterested in expansion or establishing a formal hegemony in the Greek East and maintained only very loose ties to the polities of the eastern Adriatic coast. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

A Black-Figured Kylix from the Athenian Agora

A BLACK-FIGUREDKYLIX FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATES 31 AND 32) I N THE spring of 1950 an ancientwell was discoveredin the area behindthe Stoa of Attalos, just east of the sixth shop from the south.' It was excavated to the bottom which was reached at a depth of 7.70 meters below the present surface of bedrock. The well was beautifully cut, round and true, in the soft green clayey bed- rock, and on two sides, the northwest and southwest, there was a series of fifteen footholds designed to help the workman who was digging the well in going down and coming up. No trace was found of the house that this well was designed to serve nor was the contemporary ground level preserved at any point near by. A pillaged foundation trench of classical Greek times passed over the mouth of the well except for the very northernmost segment, the broad deep footing trench for the back wall of the Stoa of Attalos passed about two meters to the west of the well, and a drain of the Roman period barely a meter to the east. The few remaining " islands " where bedrock stood to a higher level preserved no trace of ancient deposit. The fill in the upper meter or so of the well was loose bedrock without sherds. The next two meters produced scattered fragments of pottery of the first half of the sixth century B.C., one box full in all, among which we may note two black-figured frag- ments with animal friezes, rudely drawn, a fragmentary lid of a powder-box pyxis belonging to the Swan Group,2a fragment of a small late Corinthian skyphos with a zone of elongated animals, and several fragmentary unfigured kylixes, one of "komast " shape and two shaped like "Ionian" kylixes and having their off-set lips decorated inside with bands of thinned glaze.4 The next four and a half meters contained no sherds whatsoever, and the fill consisted sometimes of loose bedrock, occasionally of black mud. -

Pots, Peoples and Places in 4Th Century Apulia”

ABSTRACTS - English Alastair SMALL, University of Edinburgh. “Pots, peoples and places in 4th century Apulia” This paper is intended to provide a broad context for the more specialized studies which will follow it in the symposium. It begins with a brief description of the geographical features that make Apulia different from the rest of Italy, and the economic resources that were available for economic exploitation in the late 5th and 4th centuries BC. It then discusses the distinctive cultural characteristics of the Apulian peoples, their ethnic subdivisions, and the relationship between ethnicity and material culture. By the time that red-figured pottery began to be made in South Italy, the ethnic units were losing their relevance, and the Apulian peoples were developing the structures and institutions of city-states. A relatively small number of cities controlled large territories which included numerous smaller settlements. As the city structures developed, so too did the socio-political organization within them. There was a social and probably political / military hierarchy which is reflected in the burials of the period. The weapons and armour deposited in graves point to the military ethos of this society. It depended on the military prowess not just of an aristocratic élite, but of a large body of infantrymen who fought with both throwing and thrusting spears. Grave goods and, to a lesser extent, artefacts from excavations in settlements, illustrate the hellenization of these peoples, especially in Central Apulia where Greek cultural models were often imitated, and the Greek language was widely used. Apulian traders developed close commercial contacts with Athens as well as with the Greek (Italiote) cities on the Ionian coast. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

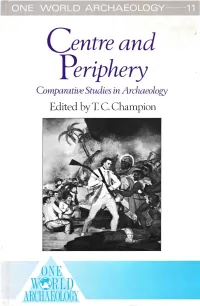

Archaeology Edited by T C

Centre and I Periphery Comparative Studies in Archaeology Edited by T C. Champion ONE W~RLD ARCHAEOLOGY '----------~~- 5 Greeks and natives in south-east Italy: approaches to the archaeological evidence RUTH D. WHITEHOUSE and JOHN B. WILKINS Introduction Recent years have seen much work on the relationship between Greeks and the populations ofsouthern Italy that were in situ before the Greeks arrived. 1 While much of this work is interesting, the majority continues to be characterized by two tendencies that we regard as unhelpful. First, there is the uncritical acceptance of the writings of Greek and Roman authors and a corresponding inclination to interpret the archaeological record in traditional historical terms, in line with the ancient authors. We have written about this elsewhere, so will not pursue it further here (Whitehouse & Wilkins 1985). Equally invidious is the strongly pro-Greek prejudice of most scholars, which leads them to regard all things Greek as inherently superior. It follows that Greekness is seen as something that other societies will acquire through simple exposure - like measles (but nicer!). These attitudes are apparent in the vocabulary used to describe the process: scholars write of the 'helleni zation' ofsouthern Italy, rather than employing terms such as 'urbanization' or 'civilization'. However, hellenization is a weak concept, lacking in analytical power, since it is evident that not all aspects ofHellenic culture are equally likely to have been adopted by the native south Italians, or at the same rate. The concept of hellenization may have some use in a restricted context, for a study of pottery styles or architecture, for instance.