THE PTOLEMIES and the 3Rd CENTURY B.C.E. CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE Melanie Godsey a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty at the University O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 3Rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT in SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA

The Roman army between the Alps and the Adriatic, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 31 / Studia Alpium et Adriae I, 2016, 99–120 THE 3rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT IN SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA Jana HORVAT, Beatriče ŽBONA TRKMAN † Abstract The significant unrest that characterized the final decades of therd 3 century lead to intensive control over communication routes and to the fortification of the most important settlements in the south-eastern Alpine area. Two assemblages originat- ing from south-western Slovenia are presented to achieve a better understanding of the period. The hoard from Prelovce near Malovše dated to the second half of the 3rd century and consisted of horse harness decoration, a military belt, and a combat knife. The hoard may suggest army movement or military control of the main road. A group of sixteen graves was found in Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and the majority of them originate from the second half of the 3rd century. The grave goods in two graves indicate a military affiliation of the deceased; a female grave containing silver jewellery corroborates the special social position of the whole group. It is possible that a military detachment was stationed at Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and controlled the road from Tarsatica to the Postojna basin. Keywords: South-western Slovenia, second half of the 3rd century, Prelovce near Malovše, Javor near Dolnji Zemon, hoards, graves, horse harness decoration, combat knives, jewellery INTRODUCTION dated in the 320s.3 The fortress at Nauportus (Vrhnika) might date at the end of the 3rd century.4 On the basis of The final decades of the 3rd century are character- coin finds it is presumed that the principia in Tarsatica ized by increasing control over communication routes were constructed at the end of the 270s or during the and by the fortification of the most important settle- 280s.5 The short-lived Pasjak fortress on the Aquileia– ments in the south-eastern Alpine area. -

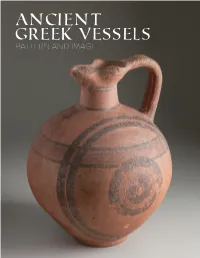

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

The Last Empire of Iran by Michael R.J

The Last Empire of Iran By Michael R.J. Bonner In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian imperial capital at Persepolis. This was the end of the world’s first great international empire. The ancient imperial traditions of the Near East had culminated in the rule of the Persian king Cyrus the Great. He and his successors united nearly all the civilised people of western Eurasia into a single state stretching, at its height, from Egypt to India. This state perished in the flames of Persepolis, but the dream of world empire never died. The Macedonian conquerors were gradually overthrown and replaced by a loose assemblage of Iranian kingdoms. The so-called Parthian Empire was a decentralised and disorderly state, but it bound together much of the sedentary Near East for about 500 years. When this empire fell in its turn, Iran got a new leader and new empire with a vengeance. The third and last pre-Islamic Iranian empire was ruled by the Sasanian dynasty from the 220s to 651 CE. Map of the Sasanian Empire. Silver coin of Ardashir I, struck at the Hamadan mint. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silver_coin_of_Ardashir_I,_struck_at_the_Hamadan _mint.jpg) The Last Empire of Iran. This period was arguably the heyday of ancient Iran – a time when Iranian military power nearly conquered the eastern Roman Empire, and when Persian culture reached its apogee before the coming of Islam. The founder of the Sasamian dynasty was Ardashir I who claimed descent from a mysterious ancestor called Sasan. Ardashir was the governor of Fars, a province in southern Iran, in the twilight days of the Parthian Empire. -

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

With Samos & Kuşadası

GREECE with Samos & Kuşadası Tour Hosts: Prof. Douglas Henry & MAY 27 - JUNE 23, 2018 Prof. Scott Moore organized by Baylor University in GREECE with Samos & Kuşadası / MAY 27 - JUNE 23, 2018 Corinth June 1 Fri Athens - Eleusis - Corinth Canal - Corinth - Nafplion (B,D) June 2 Sat Nafplion - Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon - Epidaurus - Nafplion (B, D) June 3 Sun Nafplion -Church of Agia Fotini in Mantinea- Tripolisand Megalopolis-Mystras-Kalamata (B,D) BAYLOR IN GREECE June 4 Mon Kalamata - Drive by Methoni or Koroni to see the Venetian fortresses - Nestor’s Palace in Pylos (B,D) Program Directors: Douglas Henry and Scott Moore June 5 Tue Pylos - Tours in the surrounding area - more details will follow by Nick! (B,D) MAY 27 - JUNE 23, 2018 June 6 Wed Pylos - Gortynia - Dimitsana - Olympia (B, D) June 7 Thu Olympia - Temple of Zeus, the Temple of Hera, Museum - Free afternoon. Overnight Olympia (B,D) Acropolis, Athens June 8 Fri Olympia - Morning drive to the modern city of Corinth. Overnight Corinth. (B,D) June 9 Sat Depart Corinth for Athens airport. Fly to Samos. Transfer to hotel. Free afternoon, overnight in Samos (B,D) June 10 Sun Tour of Samos; Eupalinos Tunnel, Samos Archaeological Museum, walk in Vathi port. (B,D) June 11 Mon Day trip by ferry to Patmos. Visit the Cave of Revelation and the Basilica of John. Return Samos. (B,D) June 12 Tue Depart Samos by ferry to Kusadasi. Visit Miletus- Prienne-Didyma, overnight in Kusadasi (B,D) Tour Itinerary: May 27 Sun Depart USA - Fly Athens May 28 Mon Arrive Athens Airport - Private transfer to Hotel. -

Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult

ΑΡΣΙΝΟΗ ΕΥΠΛΟΙΑ Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult Carlos Francis Robinson Bachelor of Arts (Hons. 1) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult By the early Hellenistic period a trend was emerging in which royal women were deified as Aphrodite. In a unique innovation, Queen Arsinoë II of Egypt (c. 316 – 270 BC) was deified as the maritime Aphrodite, and was associated with the cult titles Euploia, Akraia, and Galenaië. It was the important study of Robert (1966) which identified that the poets Posidippus and Callimachus were honouring Arsinoë II as the maritime Aphrodite. This thesis examines how this new third-century BC cult of ‘Arsinoë Aphrodite’ adopted aspects of Greek cults of the maritime Aphrodite, creating a new derivative cult. The main historical sources for this cult are the epigrams of Posidippus and Callimachus, including a relatively new epigram (Posidippus AB 39) published in 2001. This thesis demonstrates that the new cult of Arsinoë Aphrodite utilised existing traditions, such as: Aphrodite’s role as patron of fleets, the practice of dedications to Aphrodite by admirals, the use of invocations before sailing, and the practice of marine dedications such as shells. In this way the Ptolemies incorporated existing religious traditions into a new form of ruler cult. This study is the first attempt to trace the direct relationship between Ptolemaic ruler cult and existing traditions of the maritime Aphrodite, and deepens our understanding of the strategies of ruler cult adopted in the early Hellenistic period. -

The 3Rd Century Ce 47

the 3rd century ce 47 Chapter FOUR THE 3rd CENTURY CE Towards the 3rd century ce, recarved private por- This is an extremely difficult, if not impossible, traits, both male and female, increased in number. task and it is very doubtful that the prices given A combination of harsh economic times and a by the Diocletian price edict are trustworthy. lack of skilled artisans led to old portraits becom- Since the prices probably reflected local condi- ing a marketable commodity. For this to happen, tions in Asia Minor, they may be completely however, the Roman view of the archetype must worthless as a price indicator for the West. The have changed. In earlier periods, the archetype results of Duncan-Jones’ analyses are, nonethe- had inspired respect, even awe, but from the time less, worth mentioning here. He identified 138 of the soldier emperors onwards, attitudes different prices for Roman statues and calculated towards it must have changed to facilitate the that the mean price was about 5000 sesterces, at recarving of portraits on a large scale. least for statues in Africa (Duncan-Jones, 1974: 78; Pekàry, 1985: 19). The highest recorded price for a statue is 66,666 sesterces, followed by 50,000 Economy and reuse and 33,320 sesterces, but these amounts indicate inflation. The lowest price he found is 2000 ses- There is abundant evidence that the Roman econ- terces, whereas about 77% of all statue prices omy at least by the middle of the 3rd century ce appear to lie between 8000 and 2000 sesterces. was going through a profound crisis from which Prices also seem to include the bases. -

Siegfried Found: Decoding the Nibelungen Period

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (Gdańsk, February 2018) SIEGFRIED FOUND: DECODING THE NIBELUNGEN PERIOD CONTENTS I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? 2 II Siegfried the Dragon Slayer and the Dragon Legion of Victorinus 12 III Time of the Nibelungen. How many migration periods occurred in the 1st millennium? Who was Clovis, first King of France? 20 IV Results 34 V Bibliography 40 Acknowledgements 41 VICTORINUS (coin portrait) 2 I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? The mythical figure of Siegfried from Xanten (Colonia Ulpia Traiana), the greatest hero of the Germanic and Nordic sagas, is based on the real Gallic emperor Victorinus (meaning “the victorious”), whose name can be translated into Siegfried (Sigurd etc.), which means “victorious” in German and the Scandinavian languages. The reign of Victorinus is conventionally dated 269-271 AD. He is one of the leaders of the so-called Gallic Empire (Imperium Galliarum; 260-274 AD), mostly known from Historia Augusta (Thayer 2018), Epitome de Caesaribus of Aurelius Victor (Banchich 2009), and the Breviarum of Eutropius (Watson 1886). The capital city of this empire was Cologne, 80 km south of Xanten. Trier and Lyon were additional administrative centers. This sub-kingdom tried to defend the western part of the Roman Empire against invaders who were taking advantage of the so-called Crisis of the Third Century, which mysteriously lasted exactly 50 years (234 to 284 AD). Yet, the Gallic Empire also had separatist tendencies and sought to become independent from Rome. The bold claim of Victorinus = Siegfried was put forward, in 1841, by A. -

The Ptolemaic Sea Empire

chapter 5 The Ptolemaic Sea Empire Rolf Strootman Introduction: Empire or “Overseas Possessions”? In 1982, archaeologists of the State Hermitage Museum excavated a sanctu- ary at the site of Nymphaion on the eastern shore of the Crimea. The sanctu- ary had been in use from ca. 325 bce until its sudden abandonment around 250 bce.1 An inscription found in situ associates the site with Aphrodite and Apollo, and with a powerful local dynasty, the Spartokids.2 Built upon a rocky promontory overlooking the Kimmerian Bosporos near the port of Panti- kapaion (the seat of the Spartokids), the sanctuary clearly was linked to the sea. Most remarkable among the remains were two polychrome plastered walls covered with graffiti depicting more than 80 ships—both war galleys and cargo vessels under sail— of varying size and quality, as well as images of animals and people. The most likely interpretation of the ship images is that they were connected to votive offerings made to Aphrodite (or Apollo) in return for safe voyages.3 Most noticeable among the graffiti is a detailed, ca. 1.15 m. wide drawing of a warship, dated by the excavators to ca. 275–250, and inscribed on its prow with the name “Isis” (ΙΣΙΣ).4 The ship is commonly 1 All dates hereafter will be Before Common Era. I am grateful to Christelle Fischer-Bovet’s for her generous and critical comments. 2 SEG xxxviii 752; xxxix 701; the inscription mentions Pairisades ii, King of the Bosporos (r. 284/3– 245), and his brother. Kimmerian Bosporos is the ancient Greek name for the Chan- nel now known as the Strait of Kerch, and by extension the entire Crimea/ Sea of Azov region; see Wallace 2012 with basic bibliography. -

THE HELLENISTIC RULERS and THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* I the Beginning of the Reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II I

Originalveröffentlichung in: Ancient society 29.1998-99 (1998), S. 147-174 THE HELLENISTIC RULERS AND THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* i The beginning of the reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II in the year 145 bc following the death of his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor was described in a very negative way by ancient authors1. According to Athenaeus Ptolemy who ruled over Egypt... received from the Alexandrians appropriately the name of Malefactor. For he murdered many of the Alexandrians; not a few he sent into exile, and filled the islands and towns with men who had grown up with his brother — philologians, philosophers, mathematicians, musicians, painters, athletic trainers, physicians, and many other men of skill in their profession2. It is true that anecdotal tradition, as we find it here, is mostly of tenden tious origin, «but the course of the events suggests that the gossip-mon- * This article is the expanded version of a paper given on 2 November 1995, at the University of St Andrews, and — in a slightly changed version — on 3 November 1995, during the «Leeds Latin Seminar* on «Epigrams and Politics*. I would like to thank my colleagues there very much, especially Michael Whitby (now Warwick), for their invita tion, their hospitality, and stimulating discussions. Moreover, I would like to thank Jurgen Malitz (Eichstatt), Doris Meyer and Eckhard Wirbelauer (both Freiburg/Brsg.) for numer ous suggestions, Joachim Mathieu (Eichstatt/Atlanta) for the translation, and Roland G. Mayer (London) for his support in preparing the paper. 1 For biographical details cf. H. V olkmann , art. Ptolemaios VIII. -

The Ottoman-Venetian Border (15Th-18Th Centuries)

Hilâl. Studi turchi e ottomani 5 — The Ottoman-Venetian Border (15th-18th Centuries) Maria Pia Pedani Edizioni Ca’Foscari The Ottoman-Venetian Border (15th-18th Centuries) Hilâl Studi turchi e ottomani Collana diretta da Maria Pia Pedani Elisabetta Ragagnin 5 Edizioni Ca’Foscari Hilâl Studi turchi e ottomani Direttori | General editors Maria Pia Pedani (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Elisabetta Ragagnin (Freie Universität, Berlin) Comitato scientifico | Advisory board Bülent Arı (TBMM Milli Saraylar, Müzecilik ve Tanıtım BaŞkanı, İstanbul, Türkiye) Önder Bayır (TC BaŞbakanlık Devlet ArŞivi Daire Başkanlığı, Osmanlı Arşivi Daire Başkanlığı, İstanbul, Türkiye) Dejanirah Couto (École Pratique des Hautes Études «EPHE», Paris, France) Mehmet Yavuz Erler (Ondokuz Mayıs Üniversitesi, Samsun, Türkiye) Fabio Grassi ( «La Sapienza» Università di Roma, Italia) Figen Güner Dilek (Gazi Üniversitesi, Ankara, Türkiye) Stefan Hanß (University of Cambridge, UK) Baiarma Khabtagaeva (Szegedi Tudományegyetem, Magyarország) Nicola Melis (Università degli Studi di Cagliari, Italia) Melek Özyetgin (Yildiz Üniversitesi, İstanbul, Türkiye) Cristina Tonghini (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Direzione e redazione Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Dipartimento di Studi sull’Asia sull’Africa mediterranea Sezione Asia Orientale e Antropologia Palazzo Vendramin dei Carmini Dorsoduro 3462 30123 Venezia http://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/it/edizioni/collane/hilal/ The Ottoman-Venetian Border (15th-18th Centuries) Maria Pia Pedani translated by Mariateresa Sala Venezia Edizioni Ca’ Foscari - Digital Publishing 2017 The Ottoman-Venetian Border (15th-18th Centuries) Maria Pia Pedani © 2017 Maria Pia Pedani for the text © 2017 Mariateresa Sala for the translation © 2017 Edizioni Ca’ Foscari - Digital Publishing for the present edition Qualunque parte di questa pubblicazione può essere riprodotta, memorizzata in un sistema di recupero dati o trasmessa in qualsiasi forma o con qualsiasi mezzo, elettronico o meccanico, senza autorizzazione, a condizione che se ne citi la fonte. -

Sander-Faes (2018), Extrajudicial Settlements in The

STATO DA MAR 1 Collana della Società Dalmata di Storia Patria Atti del convegno internazionale Venezia e il suo Stato da mar / Venice and its Stato da Mar Venezia / Venice, 9-11 marzo / March 2017 a cura di Rita Tolomeo e Bruno Crevato-Selvaggi ROMA SOCIETÀ DALMATA DI STORIA PATRIA 2018 SOCIETÀ DALMATA DI STORIA PATRIA fondata a Zara nel 1926 via Fratelli Reiss Romoli 19 00143 Roma www.sddsp.it Presidente: Rita Tolomeo Stato da mar Collana della Società Dalmata di Storia Patria 1 In copertina: l’area dello Stato da mar veneziano nel dipinto di Francesco Grisellini e Giustino Menescardi, 1762 Venezia, Palazzo Ducale, Sala delle Mappe (partico- lare). 2018 © Archivio Fotografico - Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. Autorizzazione alla pubblicazione del 20 giugno 2018 (cod. ord. AF SR2017/0151). © 2018 Società Dalmata di Storia Patria Roma, La Musa Talia editrice Venezia ISBN 978-88-942382-3-5 volume pubblicato con il contributo della Regione del Veneto LR 15/1994 e del governo italiano L 72/2001 e s.m. La Musa Talìa Editrice CP 45, 30126 Lido di Venezia www.lamusatalia.it STEPHAN SANDER-FAES «TO AVOID THE COSTS OF LITIGATION, THE PARTIES COMPROMISE…» EXTRAJUDICIAL SETTLEMENTS IN THE VENETIAN COMMONWEALTH, C. 1550 Stephan Sander-Faes, University of Zurich, [email protected] Titolo. «Per evitare i costi della causa, le parti si accordano...». Accordi extragiudi- ziali nel Commonwealth veneziano, circa 1550. Keywords. Venetian Commonwealth. Crime history. Extrajudicial settlements. Everyday life. 16th century. Parole-chiave. Commonwealth veneziano. Storia dei crimini. Accordi extragiudi- ziali. Vita quotidiana. XVI secolo. Abstract This essay takes a close look at the «infrajudicial» level of conflict resolution in Ve- netian Dalmatia around the mid-16th century.