Siegfried Found: Decoding the Nibelungen Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legionary Philip Matyszak

LEGIONARY PHILIP MATYSZAK LEGIONARY The Roman Soldier’s (Unofficial) Manual With 92 illustrations To John Radford, Gunther Maser and the others from 5 Group, Mrewa. Contents Philip Matyszak has a doctorate in Roman history from St John’s College, I Joining the Roman Army 6 Oxford, and is the author of Chronicle of the Roman Republic, The Enemies of Rome, The Sons of Caesar, Ancient Rome on Five Denarii a Day and Ancient Athens on Five Drachmas a Day. He teaches an e-learning course in Ancient II The Prospective Recruit’s History for the Institute of Continuing Education at Cambridge University. Good Legion Guide 16 III Alternative Military Careers 33 HALF-TITLE Legionary’s dagger and sheath. Daggers are used for repairing tent cords, sorting out boot hobnails and general legionary maintenance, and consequently see much more use than a sword. IV Legionary Kit and Equipment 52 TITLE PAGE Trajan addresses troops after battle. A Roman general tries to be near the front lines in a fight so that he can personally comment afterwards on feats of heroism (or shirking). V Training, Discipline and Ranks 78 VI People Who Will Want to Kill You 94 First published in the United Kingdom in 2009 by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London wc1v 7qx VII Life in Camp 115 First paperback edition published in 2018 Legionary © 2009 and 2018 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London VIII On Campaign 128 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording IX How to Storm a City 149 or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

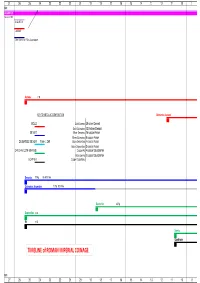

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

THE 3Rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT in SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA

The Roman army between the Alps and the Adriatic, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 31 / Studia Alpium et Adriae I, 2016, 99–120 THE 3rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT IN SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA Jana HORVAT, Beatriče ŽBONA TRKMAN † Abstract The significant unrest that characterized the final decades of therd 3 century lead to intensive control over communication routes and to the fortification of the most important settlements in the south-eastern Alpine area. Two assemblages originat- ing from south-western Slovenia are presented to achieve a better understanding of the period. The hoard from Prelovce near Malovše dated to the second half of the 3rd century and consisted of horse harness decoration, a military belt, and a combat knife. The hoard may suggest army movement or military control of the main road. A group of sixteen graves was found in Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and the majority of them originate from the second half of the 3rd century. The grave goods in two graves indicate a military affiliation of the deceased; a female grave containing silver jewellery corroborates the special social position of the whole group. It is possible that a military detachment was stationed at Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and controlled the road from Tarsatica to the Postojna basin. Keywords: South-western Slovenia, second half of the 3rd century, Prelovce near Malovše, Javor near Dolnji Zemon, hoards, graves, horse harness decoration, combat knives, jewellery INTRODUCTION dated in the 320s.3 The fortress at Nauportus (Vrhnika) might date at the end of the 3rd century.4 On the basis of The final decades of the 3rd century are character- coin finds it is presumed that the principia in Tarsatica ized by increasing control over communication routes were constructed at the end of the 270s or during the and by the fortification of the most important settle- 280s.5 The short-lived Pasjak fortress on the Aquileia– ments in the south-eastern Alpine area. -

The Last Empire of Iran by Michael R.J

The Last Empire of Iran By Michael R.J. Bonner In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian imperial capital at Persepolis. This was the end of the world’s first great international empire. The ancient imperial traditions of the Near East had culminated in the rule of the Persian king Cyrus the Great. He and his successors united nearly all the civilised people of western Eurasia into a single state stretching, at its height, from Egypt to India. This state perished in the flames of Persepolis, but the dream of world empire never died. The Macedonian conquerors were gradually overthrown and replaced by a loose assemblage of Iranian kingdoms. The so-called Parthian Empire was a decentralised and disorderly state, but it bound together much of the sedentary Near East for about 500 years. When this empire fell in its turn, Iran got a new leader and new empire with a vengeance. The third and last pre-Islamic Iranian empire was ruled by the Sasanian dynasty from the 220s to 651 CE. Map of the Sasanian Empire. Silver coin of Ardashir I, struck at the Hamadan mint. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silver_coin_of_Ardashir_I,_struck_at_the_Hamadan _mint.jpg) The Last Empire of Iran. This period was arguably the heyday of ancient Iran – a time when Iranian military power nearly conquered the eastern Roman Empire, and when Persian culture reached its apogee before the coming of Islam. The founder of the Sasamian dynasty was Ardashir I who claimed descent from a mysterious ancestor called Sasan. Ardashir was the governor of Fars, a province in southern Iran, in the twilight days of the Parthian Empire. -

'Native Interaction Across the Frontier Zone of Hadrian's Wall'

The University of Nottingham Department of Archaeology ‘Native Interaction Across The Frontier Zone Of Hadrian’s Wall’ By Penny Trichler Module MR4120 Dissertation presented for MA (by Research) In Archaeology, November 2015 1 I certify that: a) The following dissertation is my own original work. b) The source of all non-original material is clearly indicated. c) All material presented by me for other modules is clearly indicated. d) All assistance received has been acknowledged. Signed: Penny Trichler 30/11/2015 2 Acknowledgements This project has relied mainly on the help and guidance of supervisor Professor Will Bowden who gave his time and expertise to aid in the creation of this research. I would also like to thank all at the Department of Archaeology at the University of Nottingham for their support and direction. 3 Abstract This dissertation will look at the transition from the Late Pre-Roman Iron Age through to the Roman period in what is today’s northern England and Scotland, specifically looking at the native communities and their interaction across and around the frontier of Hadrian’s Wall. It will compare the engagement of native peoples on either side of the frontier zone with each other and with the Romans occupying the Wall. This research expands the recent thinking that has been developing over the last few years in this area of study, the idea of a frontier zone with both native and military elements interacting, rather than a pure military barrier. It also looks to expand the knowledge of the native peoples engagement with each other across Hadrian’s Wall frontier as well as with Roman culture on the boundaries of the Empire. -

Germania TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 16 TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 17

TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 15 Part I Germania TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 16 TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 17 1 Land and People The Land The heartland of the immense area of northern Europe occupied by the early Germanic peoples was the great expanse of lowland which extends from the Netherlands to western Russia. There are no heights here over 300 metres and most of the land rises no higher than 100 metres. But there is considerable variety in relief and soil conditions. Several areas, like the Lüneburg Heath and the hills of Schleswig-Holstein, are diverse in both relief and landscape. There was until recent times a good deal of marshy ground in the northern parts of the great plain, and a broad belt of coastal marshland girds it on its northern flank. Several major rivers drain the plain, the Ems, Weser and Elbe flowing into the North Sea, the Oder and the Vistula into the Baltic. Their broad valleys offered attrac- tive areas for early settlement, as well as corridors of communication from south to north. The surface deposits on the lowland largely result from successive periods of glaciation. A major influence on relief are the ground moraines, comprising a stiff boulder clay which produces gently undu- lating plains or a terrain of small, steep-sided hills and hollows, the latter often containing small lakes and marshes, as in the area around Berlin. Other features of the relief are the hills left behind by terminal glacial moraines, the sinuous lakes which are the remains of melt-water, and the embayments created by the sea intruding behind a moraine. -

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

The meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Originally translated by Meric Casaubon About this edition Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus was Emperor of Rome from 161 to his death, the last of the “Five Good Emperors.” He was nephew, son-in-law, and adoptive son of Antonius Pius. Marcus Aurelius was one of the most important Stoic philosophers, cited by H.P. Blavatsky amongst famous classic sages and writers such as Plato, Eu- ripides, Socrates, Aristophanes, Pindar, Plutarch, Isocrates, Diodorus, Cicero, and Epictetus.1 This edition was originally translated out of the Greek by Meric Casaubon in 1634 as “The Golden Book of Marcus Aurelius,” with an Introduction by W.H.D. Rouse. It was subsequently edited by Ernest Rhys. London: J.M. Dent & Co; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co, 1906; Everyman’s Library. 1 Cf. Blavatsky Collected Writings, (THE ORIGIN OF THE MYSTERIES) XIV p. 257 Marcus Aurelius' Meditations - tr. Casaubon v. 8.16, uploaded to www.philaletheians.co.uk, 14 July 2013 Page 1 of 128 LIVING THE LIFE SERIES MEDITATIONS OF MARCUS AURELIUS Chief English translations of Marcus Aurelius Meric Casaubon, 1634; Jeremy Collier, 1701; James Thomson, 1747; R. Graves, 1792; H. McCormac, 1844; George Long, 1862; G.H. Rendall, 1898; and J. Jackson, 1906. Renan’s “Marc-Aurèle” — in his “History of the Origins of Christianity,” which ap- peared in 1882 — is the most vital and original book to be had relating to the time of Marcus Aurelius. Pater’s “Marius the Epicurean” forms another outside commentary, which is of service in the imaginative attempt to create again the period.2 Contents Introduction 3 THE FIRST BOOK 12 THE SECOND BOOK 19 THE THIRD BOOK 23 THE FOURTH BOOK 29 THE FIFTH BOOK 38 THE SIXTH BOOK 47 THE SEVENTH BOOK 57 THE EIGHTH BOOK 67 THE NINTH BOOK 77 THE TENTH BOOK 86 THE ELEVENTH BOOK 96 THE TWELFTH BOOK 104 Appendix 110 Notes 122 Glossary 123 A parting thought 128 2 [Brought forward from p. -

Bullard Eva 2013 MA.Pdf

Marcomannia in the making. by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies Eva Bullard 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Marcomannia in the making by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member During the last stages of the Marcommani Wars in the late second century A.D., Roman literary sources recorded that the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was planning to annex the Germanic territory of the Marcomannic and Quadic tribes. This work will propose that Marcus Aurelius was going to create a province called Marcomannia. The thesis will be supported by archaeological data originating from excavations in the Roman installation at Mušov, Moravia, Czech Republic. The investigation will examine the history of the non-Roman region beyond the northern Danubian frontier, the character of Roman occupation and creation of other Roman provinces on the Danube, and consult primary sources and modern research on the topic of Roman expansion and empire building during the principate. iv Table of Contents Supervisory Committee ..................................................................................................... -

ROMANIZATION and SOME CILICIAN CULTS by HUGH ELTON (BIAA)

ROMANIZATION AND SOME CILICIAN CULTS By HUGH ELTON (BIAA) This paper focuses on two sites from central Cilicia in Anatolia, the Cory cian Cave and Kanhdivane, to make some comments about religion and Romanization. From the Corycian Cave, a pair of early third-century AD altars are dedicated to Zeus Korykios, described as Victorious (Epinikios), Triumphant (Tropaiuchos), and the Harvester (Epikarpios), and to Hermes Korykios, also Victorious, Triumphant, and the Harvester. The altars were erected for 'the fruitfulness and brotherly love of the Augusti', suggesting they come from the period before Geta's murder, i.e. between AD 209 and 212. 1 These altars are unremarkable and similar examples are common else where, so these altars can be interpreted as showing the homogenising effect of the Roman Empire. But behind these dedications, however, may lie a re ligious tradition stretching back to the second millennium BC. At the second site, Kanhdivane, a tomb in the west necropolis was accompanied by a fu nerary inscription erected by Marcus Ulpius Knos for himself and his family, probably in the second century AD. Marcus then added, 'but if anyone damages or opens [the tomb] let him pay to the treasury of Zeus 1000 [de narii] and to the Moon (Selene) and to the Sun (Helios) above 1000 [denarii] and let him be subject to the curses also of the Underground Gods (Kata chthoniai Theoi). ' 2 When he wanted to threaten retribution, Knos turned to a local group of gods. As at the Corycian Cave, Knos' actions may preserve traces of pre-Roman practices, though within a Roman framework. -

Coin Hoards from the British Isles 2015

COIN HOARDS FROM THE BRITISH ISLES 2015 EDITED BY RICHARD ABDY, MARTIN ALLEN AND JOHN NAYLOR BETWEEN 1975 and 1985 the Royal Numismatic Society published summaries of coin hoards from the British Isles and elsewhere in its serial publication Coin Hoards, and in 1994 this was revived as a separate section in the Numismatic Chronicle. In recent years the listing of finds from England, Wales and Northern Ireland in Coin Hoards was principally derived from reports originally prepared for publication in the Treasure Annual Report, but the last hoards published in this form were those reported under the 1996 Treasure Act in 2008. In 2012 it was decided to publish summaries of hoards from England, Wales, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland and the Channel Islands in the British Numismatic Journal on an annual basis. The hoards are listed in two sections, with the first section consisting of summaries of Roman hoards, and the second section providing more concise summaries of medieval and post-medieval hoards. In both sections the summaries include the place of finding, the date(s) of discovery, the suggested date(s) of deposition, and the number allocated to the hoard when it was reported under the terms of the Treasure Act (in England and Wales) or the laws of Treasure Trove (in Scotland). For reasons of space names of finders are omitted from the sum- mary of medieval and post-medieval hoards. Reports on most of the English and Welsh hoards listed are available online from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) website: select the ‘Search our database’ bar under finds.org.uk/database, and type in the treasure case number without spaces (e.g. -

The History of Transylvania and the Transylvanian

Transylvania Online THE HISTORY OF TRANSYLVANIA AND THE TRANSYLVANIAN SAXONS by Dr. Konrad Gündisch, Oldenburg, Germany Contents: 1. The Region: Land and People 1.1. Geography 1.2. Population and Ancient History 1.2.1. Prehistoric Era 1.2.2. Dacians and Romans 1.2.3. Period of Mass Folk Migrations 1.2.4 Integration into the Medieval Hungarian kingdom 2. The Migration and Settlement of the Transylvanian Saxons 2.1. The Hungarian Crown of King Stephen as "Host" 2.2. Origin of the Transylvanian Saxons 2.3. Progression of the Settlements 2.3.1. Beginning 2.3.2. Stages of Colonization 2.3.2.1. The Teutonic Knights in the Burzenland (Tara Bârsei) 2.3.3. Privileges 3. Political History and Economic Development During the Middle Ages 4. Early Recent History: Autonomous Principality Transylvania 5. Province of the Hapsburg Empire 6. Part of the Kingdom of Greater Romania 7. Under Communist Rule Centuries of History Fading "Siebenbürgen und die Siebenbürger Sachsen" was written in German by Dr. Konrad Gündisch, Oldenburg, Germany. The English translation "Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons" was written by Georg Schuller, Edmonton, Canada. 1. The Region: Land and People 1.1. Geography Atlantean and satellite maps of eastern Europe show the topography of Transylvania as a clearly definable geographic region. It is comparable with a natural fortress, a mountainous region almost completely barrier-like enclosed by the East and South Carpathians and the Transylvanian West Mountains, sheltering the Transylvanian Depression in the centre. This Transylvanian Basin or Plateau is partitioned by three rivers, the Mures, Olsul and Somesu (Mieresch, Alt/Olt, Somesch), all tributaries of the Danube. -

Sau Angle Head Holder

ANGLE HEAD HOLDER CATEGORY SAU ANGLE HEAD HOLDER [UNIVERSAL TYPE] S-2 SAR ANGLE HEAD HOLDER S-3~6 SAC ANGLE HEAD HOLDER S-7~16 SAM ANGLE HEAD HOLDER S-17~26 SAG ANGLE HEAD HOLDER [SLIM TYPE] S-27 SAD ANGLE HEAD HOLDER [SLIM TYPE] S-28 FIXED BLOCK S-30~31 ANGLE HEAD HOLDERS SAU ANGLE HEAD HOLDER UNIVERSAL TYPE FOR MIDDLE CUTTING SAU 萬向銑削頭 □ □ WEIGHT SHANK MODEL NO. TYPE L l1 S TORQUE COLLET SIZE RANGE (KGS) 12.789.32.328 BT50 x SAU32E - 328 328 200 110 40 N-m ER32 2 ~ 20 20.9 MAS 403 INCHES 32.789.32.131 CAT50 x SAU32E - 13.1'' 13.1 7.87 4.33 40 N-m ER32 2 ~ 20 21.5 ANSI B5.50 Product information: ▸ Gear ratio 1:1. ▸ Max. revolution: 3000rpm. ▸ Max. torque: 40N-m. ▸ Suggested Ap ≤ 4mm. ▸ Adjustable spindle angle from 0° to 90° on inclined surfaces. ▸ Adjustable angle increment: 1°. ▸ Internal coolant not available. ▸ Turn counterclockwise. ▸ Can be used for ATC. S-2 General catalogue SAR ANGLE HEAD HOLDER FOR HEAVY-DUTY CUTTING SAR 大鋼炮銑削頭 (SBT TYPE) 2 L 45 ANGLE HEAD HOLDERS ψ225 10 65 ψ125 R18 s 87.8 45 45 TW PAT NO. M420384 97 CN PAT NO. ZL201120430504.9 WEIGHT SHANK MODEL NO. TYPE L S TORQUE (KGS) 12.643 BT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230 230 80 50 N-m 16.1 12.643S BT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230S 230 110 50 N-m 16.1 MAS 403 27.643 SBT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230 230 80 50 N-m 16.1 27.643S SBT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230S 230 110 50 N-m 16.1 DaulDRIVE+ 32.643 CAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230 234.95 80 50 N-m 16.1 32.643S CAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230S 234.95 110 50 N-m 16.1 ANSI B5.50 44.643 SCAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230 234.95 80 50 N-m 16.1 44.643S SCAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230S 234.95 110 50 N-m 16.1 DaulDRIVE+ 52.643 DAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230 235 80 50 N-m 16.1 52.643S DAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230S 235 110 50 N-m 16.1 DIN 69871-A 67.643 SDAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230 235 80 50 N-m 16.1 67.643S SDAT50 x SAR50 / SBT30 - 230S 235 110 50 N-m 16.1 DaulDRIVE+ Product information: ▸ Gear ratio 1:1.