Coin Hoards from the British Isles 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

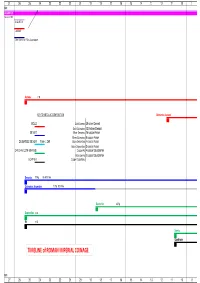

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION It may be worth explaining why this collection has concentrated on a series of coins which has been, at least until quite re- cently, deeply unfashionable. It would be difficult to argue for the artistic merits of mid third-century coins, and the technical skills apparent in both die-engraving and striking are frequently low. The formation of this collection has passed through a number of successive phases, in fact, with different motivations in each case. When I first started to collect Roman coins, as a university student in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the main attraction of coins of emperors such as Gallienus and Claudius II was that many of them could be obtained without large financial outlay. Common types could be purchased for just a pound or two each. Once in paid employment I was able to expand the range of my collecting to some extent, but I very soon discovered that many of my colleagues in the archaeology and museum profes- sions were deeply opposed to the idea of those employed in this type of work forming private collections at all – an attitude which unfortunately still persists in some quarters today. I disagree with this fundamentally, as I believe that those who are fortunate enough to be able to accumulate numismatic knowledge in the course of their employment are best placed to carry out research on, and publish discussion of, interesting items which appear on the open market. I do, however, accept that it is at the very least unwise to collect in the same field as an institution where one is employed, as aspersions can be cast, however unjustly, and these may harm one’s reputation. -

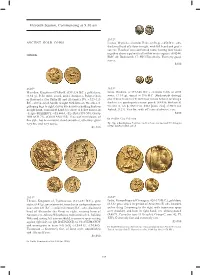

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

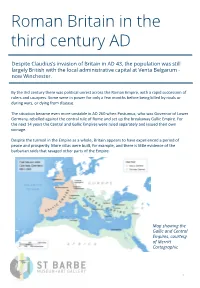

Roman Britain in the Third Century AD

Roman Britain in the third century AD Despite Claudius’s invasion of Britain in AD 43, the population was still largely British with the local administrative capital at Venta Belgarum - now Winchester. By the 3rd century there was political unrest across the Roman Empire, with a rapid succession of rulers and usurpers. Some were in power for only a few months before being killed by rivals or during wars, or dying from disease. The situation became even more unstable in AD 260 when Postumus, who was Governor of Lower Germany, rebelled against the central rule of Rome and set up the breakaway Gallic Empire. For the next 14 years the Central and Gallic Empires were ruled separately and issued their own coinage. Despite the turmoil in the Empire as a whole, Britain appears to have experienced a period of peace and prosperity. More villas were built, for example, and there is little evidence of the barbarian raids that ravaged other parts of the Empire. Map showing the Gallic and Central Empires, courtesy of Merritt Cartographic 1 The Boldre Hoard The Boldre Hoard contains 1,608 coins, dating from AD 249 to 276 and issued by 12 different emperors. The coins are all radiates, so-called because of the radiate crown worn by the emperors they depict. Although silver, the coins contain so little of that metal (sometimes only 1%) that they appear bronze. Many of the coins in the Boldre Hoard are extremely common, but some unusual examples are also present. There are three coins of Marius, for example, which are scarce in Britain as he ruled the Gallic Empire for just 12 weeks in AD 269. -

Collector's Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage

Liberty Coin Service Collector’s Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage (49 BC - AD 518) The Twelve Caesars - The Julio-Claudians and the Flavians (49 BC - AD 96) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Julius Caesar (49-44 BC) Augustus (31 BC-AD 14) Tiberius (AD 14 - AD 37) Caligula (AD 37 - AD 41) Claudius (AD 41 - AD 54) Tiberius Nero (AD 54 - AD 68) Galba (AD 68 - AD 69) Otho (AD 69) Nero Vitellius (AD 69) Vespasian (AD 69 - AD 79) Otho Titus (AD 79 - AD 81) Domitian (AD 81 - AD 96) The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (AD 96 - AD 192) Nerva (AD 96-AD 98) Trajan (AD 98-AD 117) Hadrian (AD 117 - AD 138) Antoninus Pius (AD 138 - AD 161) Marcus Aurelius (AD 161 - AD 180) Hadrian Lucius Verus (AD 161 - AD 169) Commodus (AD 177 - AD 192) Marcus Aurelius Years of Transition (AD 193 - AD 195) Pertinax (AD 193) Didius Julianus (AD 193) Pescennius Niger (AD 193) Clodius Albinus (AD 193- AD 195) The Severans (AD 193 - AD 235) Clodius Albinus Septimus Severus (AD 193 - AD 211) Caracalla (AD 198 - AD 217) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Geta (AD 209 - AD 212) Macrinus (AD 217 - AD 218) Diadumedian as Caesar (AD 217 - AD 218) Elagabalus (AD 218 - AD 222) Severus Alexander (AD 222 - AD 235) Severus The Military Emperors (AD 235 - AD 284) Alexander Maximinus (AD 235 - AD 238) Maximus Caesar (AD 235 - AD 238) Balbinus (AD 238) Maximinus Pupienus (AD 238) Gordian I (AD 238) Gordian II (AD 238) Gordian III (AD 238 - AD 244) Philip I (AD 244 - AD 249) Philip II (AD 247 - AD 249) Gordian III Trajan Decius (AD 249 - AD 251) Herennius Etruscus -

Siegfried Found: Decoding the Nibelungen Period

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (Gdańsk, February 2018) SIEGFRIED FOUND: DECODING THE NIBELUNGEN PERIOD CONTENTS I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? 2 II Siegfried the Dragon Slayer and the Dragon Legion of Victorinus 12 III Time of the Nibelungen. How many migration periods occurred in the 1st millennium? Who was Clovis, first King of France? 20 IV Results 34 V Bibliography 40 Acknowledgements 41 VICTORINUS (coin portrait) 2 I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? The mythical figure of Siegfried from Xanten (Colonia Ulpia Traiana), the greatest hero of the Germanic and Nordic sagas, is based on the real Gallic emperor Victorinus (meaning “the victorious”), whose name can be translated into Siegfried (Sigurd etc.), which means “victorious” in German and the Scandinavian languages. The reign of Victorinus is conventionally dated 269-271 AD. He is one of the leaders of the so-called Gallic Empire (Imperium Galliarum; 260-274 AD), mostly known from Historia Augusta (Thayer 2018), Epitome de Caesaribus of Aurelius Victor (Banchich 2009), and the Breviarum of Eutropius (Watson 1886). The capital city of this empire was Cologne, 80 km south of Xanten. Trier and Lyon were additional administrative centers. This sub-kingdom tried to defend the western part of the Roman Empire against invaders who were taking advantage of the so-called Crisis of the Third Century, which mysteriously lasted exactly 50 years (234 to 284 AD). Yet, the Gallic Empire also had separatist tendencies and sought to become independent from Rome. The bold claim of Victorinus = Siegfried was put forward, in 1841, by A. -

THE FRACTURE of IMPERIAL ROME the Rise and Fall of the Gallic Empire 260-274 CE a Set of Eight Bronze Coins

THE FRACTURE OF IMPERIAL ROME The Rise and Fall of the Gallic Empire 260-274 CE A Set of Eight Bronze Coins Coin type and grade may vary Order code: 8GALLICEMPBOX somewhat from image Beginning with the reign of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, the Roman Empire enjoyed two full centuries of peace and prosperity. The Pax Romana was unprecedented in both duration and territory—at its height, Rome controlled the entire Mediterranean region: most of Europe, including Britannia; all of North Africa from Gibraltar to Egypt; and a vast swath of the Middle East stretching into Mesopotamia and the Caucasus. Governing that many diverse populations so effectively, and for so long, is a feat unrivaled in the annals of history. To do so, the Romans established the most efficient system of administration the world had ever known. Career bureaucrats—prefects, politicians, tax collectors—maintained the system regardless of who was seated on the throne. During the Pax Romana, Rome also boasted a series of strong, stable emperors. Although there were periods of unrest, these tended to be short. After the death of Nero, three family dynasties provided the Empire with a consistent succession of emperors. By the third century CE, the empire began to show signs of collapse. A parade of emperors took the throne, mostly from the ranks of the military. Years of civil war and open revolt led to an erosion of territory. In the year 260, in a battle on the Eastern front, the Emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by the hated Persians. He died in captivity, and his corpse was stuffed and hung on the wall of the palace of the Persian king. -

On the Roman Frontier1

Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Impact of Empire Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.–A.D. 476 Edited by Olivier Hekster (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Lukas de Blois Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt Elio Lo Cascio Michael Peachin John Rich Christian Witschel VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/imem Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016036673 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1572-0500 isbn 978-90-04-32561-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32675-0 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Stoke Lyne Coin Hoards and the Roman Crisis of the Third Century

Stoke Lyne coin hoards and the Roman Crisis of the Third Century Oxfordshire Museum and Oxfordshire Museum Services are pursuing the possible acquisition of two Roman coin hoards found by a metal detectorist in 2016 near Stoke Lyne (near Bicester). The total number of coins in the hoards is approximately 2200 and the majority of the coins date from the late third century AD. The earliest coins have a higher silver content but the bulk of the hoard is made up of a debased copper alloy coinage. The earliest coins would seem have been struck between 271 AD and 284 AD. The coins are not of high commercial value but help to consolidate and extend our knowledge of the Roman presence in North Oxfordshire. The coins in the hoards were struck in one of the most chaotic periods of the later Roman Empire. The Roman period, 235 - 284 AD, has been called, by later historians, ‘The Crisis of the Third Century’. For a short time, the Empire became ungovernable as a single unit and split into three components under three or more different leaders and warlords. After this short period of instability, the Empire was temporarily re-united under Aurelian (284 AD) and then formally split by Diocletian (293 AD) into a Western half to be centred on Rome and an Eastern half to be centred on Nicomedia and other eastern cities. Simply put, the Empire had become too big with too huge borders to be governed centrally from Rome in an age of increasing barbarian activity and economic complexity. -

PDF Printing 600

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE ET DE SIGILLOGRAPHIE BELGISCH TIJDSCHRIFT VOOR NlTMISMATIEI( EN ZEGELI(IJNDE PUBLIÉE UI1'GEGEVEN SOllS LE HAllT PATRONAGE ONDER DE HOGE BESCHERMING DE S. M. LE ROI VAN Z. M. DE KONING PAR LA DOOR HET SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE KONINKLIJK BELGISCH DE NUMISMATIQUE DE BELGIQUE GENOOTSCIIAP VOOR NUMISMATIEK Directeurs GHISLAINE MOUCI-IARTE, PIERRE COCKSHAW, FRANÇOIS DE CALLATAY et JOHAN VAN HEESCH CXLVIII - 2002 BRUXELLES BRUSSEL GIJS DE GREEF (*) ROMAN COIN HOARDS AND GERMANIe INVASIONS AD 253·269. A STUDY OF THE WESTERN HOARDS FROM THE REIGNS OF VALERIAN, GALLIENUS AND POSTUMUS C) Introduction A lamanni, oastaiis Galliis, in ltaliam penelraueruni. Dacia, quae a Traiano ultra Danubium [ueral adiecia, amissa est. Graecia, Macedonia, Pontus, Asta, oasiaia est per Gothos. Pannonia a Sarmatis Quadisque popu lata est. Germani usque ad Hispanias peneiraoeruni et cioitaiem nobilem Tarraconem expugnaverunl. Parihi, Mesopolamia occupata, Syriam sibi coe perunl nitulicare. Eutropius, Breuiarutn, IX, 8 With these dramatic words Eutropius and other Roman authors de scrîbed the events, which took place under the reign of the emperors Va lerian (253-260), Gallienus (253-268) and Postumus (260-269). However, the nature, the ehronologîeal and geographical spread and the impact of these invasions remain mostly unknown. The combined evidenee of texts, epigraphy, numismatics and archaeology has been proven incapable of solvîng these problems. This is why, from the beginning of the 20th cen tury, many scholars have sought a link between the Germanie invasions and the hundreds of coin hoards from this period which have been found ail over Europe e). This, in sorne cases aIl to automatically supposed, Iink between hoard and invasion has been severely critized over the last (*) Gijs DE GREEF, Kloosterstraat 58, B-3150 Haacht. -

Athenian Agora ® Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND

THE ATHENIANAGORA RESULTS OF EXCAVATIONS CONDUCTED BY THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS VOLUME II Athens COINS at FROM THE ROMAN THROUGH THE VENETIAN PERIOD BY Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. MARGARET THOMPSON License: Classical of fbj AP A J only. Ak~ use School personal American © For THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY I954 American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to The Athenian Agora ® www.jstor.org Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. License: Classical PRINTED of only. use IN School GERMANY ALL RIGHTS personal at American J.J.AUGUSTIN RESERVED © For GLOCKSTADT PREFACE Between the years 1931 and 1949 the American excavations in the Athenian Agora produced 55,492 coins of Roman and later periods. The catalogued entries in this publication, ranging in date from the last century of the Roman Republic to the declining years of the Republic of Venice, total 37,090 specimens; the remaining Islamic and Modern Greek pieces have been Athens listed summarily in order that the tally may be complete. This is an overwhelming amount of at coinage, which in sheer quantity represents a collection comparableto many in the numismatic museums of the world. Unfortunately very few of the Agora coins are museum pieces, but lamentable as is their general condition to the eye of the coin collector or the cataloguer, they do provide for the historian an invaluable record of the money circulating in one of the chief cities of from the time of Sulla to our own Studies antiquity present. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 01:07:49PM Via Free Access MAPPING the CRISIS of the THIRD CENTURY

EPILOGUE John Nicols - 9789047420903 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 01:07:49PM via free access MAPPING THE CRISIS OF THE THIRD CENTURY John Nicols The Greek philosopher and sophist Protagoras would surely not mind this reuse of one of his most famous statements. “Concerning the crisis of the third century, I have no means of knowing whether there was one or not, or of what sort of a crisis it may have been. Many things prevent knowledge including the obscurity of the subject and the brevity of human life.”1 Within these proceedings one nds striking disagreement about whether there was a crisis as the term has been conventionally understood. And, if there was one, when did it begin? Dictionaries de ne our word crisis as: “An unstable condition, as in political, social, or economic affairs, involving an impending abrupt or decisive change”. During the years 235 to 285, the Roman Empire surely did enter a period of instability. The patterns of ‘emperor mak- ing and breaking’ and of barbarian invasion during this period mark in my estimation the characteristics of a major political crisis. Indeed, when one compares the overall stability of the Roman imperial system and government of the mid-second to that of the mid-third century, the differences are readily apparent both in terms of leadership and defense.2 In sum, that there was a ‘crisis’ is a fundamental assumption of this paper; but it is also a demonstrable proposition. I am moreover especially concerned here not only how to understand the nature of the crisis as a complex set of related events, but also how to explain the complexities of the crisis to others, especially to students.