Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Coin Hoards from the British Isles 2015

COIN HOARDS FROM THE BRITISH ISLES 2015 EDITED BY RICHARD ABDY, MARTIN ALLEN AND JOHN NAYLOR BETWEEN 1975 and 1985 the Royal Numismatic Society published summaries of coin hoards from the British Isles and elsewhere in its serial publication Coin Hoards, and in 1994 this was revived as a separate section in the Numismatic Chronicle. In recent years the listing of finds from England, Wales and Northern Ireland in Coin Hoards was principally derived from reports originally prepared for publication in the Treasure Annual Report, but the last hoards published in this form were those reported under the 1996 Treasure Act in 2008. In 2012 it was decided to publish summaries of hoards from England, Wales, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland and the Channel Islands in the British Numismatic Journal on an annual basis. The hoards are listed in two sections, with the first section consisting of summaries of Roman hoards, and the second section providing more concise summaries of medieval and post-medieval hoards. In both sections the summaries include the place of finding, the date(s) of discovery, the suggested date(s) of deposition, and the number allocated to the hoard when it was reported under the terms of the Treasure Act (in England and Wales) or the laws of Treasure Trove (in Scotland). For reasons of space names of finders are omitted from the sum- mary of medieval and post-medieval hoards. Reports on most of the English and Welsh hoards listed are available online from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) website: select the ‘Search our database’ bar under finds.org.uk/database, and type in the treasure case number without spaces (e.g. -

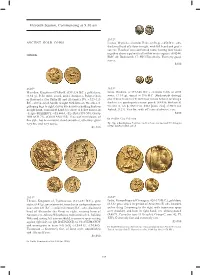

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

Collector's Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage

Liberty Coin Service Collector’s Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage (49 BC - AD 518) The Twelve Caesars - The Julio-Claudians and the Flavians (49 BC - AD 96) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Julius Caesar (49-44 BC) Augustus (31 BC-AD 14) Tiberius (AD 14 - AD 37) Caligula (AD 37 - AD 41) Claudius (AD 41 - AD 54) Tiberius Nero (AD 54 - AD 68) Galba (AD 68 - AD 69) Otho (AD 69) Nero Vitellius (AD 69) Vespasian (AD 69 - AD 79) Otho Titus (AD 79 - AD 81) Domitian (AD 81 - AD 96) The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (AD 96 - AD 192) Nerva (AD 96-AD 98) Trajan (AD 98-AD 117) Hadrian (AD 117 - AD 138) Antoninus Pius (AD 138 - AD 161) Marcus Aurelius (AD 161 - AD 180) Hadrian Lucius Verus (AD 161 - AD 169) Commodus (AD 177 - AD 192) Marcus Aurelius Years of Transition (AD 193 - AD 195) Pertinax (AD 193) Didius Julianus (AD 193) Pescennius Niger (AD 193) Clodius Albinus (AD 193- AD 195) The Severans (AD 193 - AD 235) Clodius Albinus Septimus Severus (AD 193 - AD 211) Caracalla (AD 198 - AD 217) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Geta (AD 209 - AD 212) Macrinus (AD 217 - AD 218) Diadumedian as Caesar (AD 217 - AD 218) Elagabalus (AD 218 - AD 222) Severus Alexander (AD 222 - AD 235) Severus The Military Emperors (AD 235 - AD 284) Alexander Maximinus (AD 235 - AD 238) Maximus Caesar (AD 235 - AD 238) Balbinus (AD 238) Maximinus Pupienus (AD 238) Gordian I (AD 238) Gordian II (AD 238) Gordian III (AD 238 - AD 244) Philip I (AD 244 - AD 249) Philip II (AD 247 - AD 249) Gordian III Trajan Decius (AD 249 - AD 251) Herennius Etruscus -

The Epitome De Caesaribus and the Thirty Tyrants

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ELTE Digital Institutional Repository (EDIT) THE EPITOME DE CAESARIBUS AND THE THIRTY TYRANTS MÁRK SÓLYOM The Epitome de Caesaribus is a short, summarizing Latin historical work known as a breviarium or epitomé. This brief summary was written in the late 4th or early 5th century and summarizes the history of the Roman Empire from the time of Augustus to the time of Theodosius the Great in 48 chapters. Between chapters 32 and 35, the Epitome tells the story of the Empire under Gallienus, Claudius Gothicus, Quintillus, and Aurelian. This was the most anarchic time of the soldier-emperor era; the imperatores had to face not only the German and Sassanid attacks, but also the economic crisis, the plague and the counter-emperors, as well. The Scriptores Historiae Augustae calls these counter-emperors the “thirty tyrants” and lists 32 usurpers, although there are some fictive imperatores in that list too. The Epitome knows only 9 tyrants, mostly the Gallic and Western usurpers. The goal of my paper is to analyse the Epitome’s chapters about Gallienus’, Claudius Gothicus’ and Aurelian’s counter-emperors with the help of the ancient sources and modern works. The Epitome de Caesaribus is a short, summarizing Latin historical work known as a breviarium or epitomé (ἐπιτομή). During the late Roman Empire, long historical works (for example the books of Livy, Tacitus, Suetonius, Cassius Dio etc.) fell out of favour, as the imperial court preferred to read shorter summaries. Consequently, the genre of abbreviated history became well-recognised.1 The word epitomé comes from the Greek word epitemnein (ἐπιτέμνειν), which means “to cut short”.2 The most famous late antique abbreviated histories are Aurelius Victor’s Liber de Caesaribus (written in the 360s),3 Eutropius’ Breviarium ab Urbe condita4 and Festus’ Breviarium rerum gestarum populi Romani.5 Both Eutropius’ and Festus’ works were created during the reign of Emperor Valens between 364 and 378. -

Name Reign Succession Died

Name Reign Succession Died March 20, 235 CE - Proclaimed emperor by German legions April 238 CE; Assasinated by Praetorian Maximinus I April 238 CE after the murder of Severus Alexander Guard Proclaimed emperor, whilst Pro-consul in Africa, during a revolt against Maximinus. Ruled jointly with his son Gordian II, and in opposition to Maximinus. Technically a usurper, but March 22, 238 CE - retrospectively legitimised by the April 238 CE; Committed suicide upon Gordian I April 12, 238 CE accession of Gordian III hearing of the death of Gordian II. Proclaimed emperor, alongside father March 22, 238 CE - Gordian I, in opposition to Maximinus by April 238 CE; Killed during the Battle of Gordian II April 12, 238 CE act of the Senate Carthage fighting a pro-Maximinus army Proclaimed joint emperor with Balbinus by the Senate in opposition to April 22, 238 AD – Maximinus; later co-emperor with July 29, 238 CE; Assassinated by the Pupienus July 29, 238 AD Balbinus. Praetorian Guard Proclaimed joint emperor with Pupienus by the Senate after death of Gordian I & April 22, 238 AD – II, in opposition to Maximinus; later co- July 29, 238 CE; Assassinated by the Balbinus July 29, 238 AD emperor with Pupienus and Gordian III Praetorian Guard Proclaimed emperor by supporters of April 22, 238 AD – Gordian I & II, then by the Senate; joint February 11, 244 emperor with Pupienus and Balbinus February 11, 244 CE; Unknown, possibly Gordian III AD until July 238 AD. murdered on orders of Philip I February 244 AD – Praetorian Prefect to Gordian III, took September/October -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements. -

PDF Printing 600

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE ET DE SIGILLOGRAPHIE BELGISCH TIJDSCHRIFT VOOR NlTMISMATIEI( EN ZEGELI(IJNDE PUBLIÉE UI1'GEGEVEN SOllS LE HAllT PATRONAGE ONDER DE HOGE BESCHERMING DE S. M. LE ROI VAN Z. M. DE KONING PAR LA DOOR HET SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE KONINKLIJK BELGISCH DE NUMISMATIQUE DE BELGIQUE GENOOTSCIIAP VOOR NUMISMATIEK Directeurs GHISLAINE MOUCI-IARTE, PIERRE COCKSHAW, FRANÇOIS DE CALLATAY et JOHAN VAN HEESCH CXLVIII - 2002 BRUXELLES BRUSSEL GIJS DE GREEF (*) ROMAN COIN HOARDS AND GERMANIe INVASIONS AD 253·269. A STUDY OF THE WESTERN HOARDS FROM THE REIGNS OF VALERIAN, GALLIENUS AND POSTUMUS C) Introduction A lamanni, oastaiis Galliis, in ltaliam penelraueruni. Dacia, quae a Traiano ultra Danubium [ueral adiecia, amissa est. Graecia, Macedonia, Pontus, Asta, oasiaia est per Gothos. Pannonia a Sarmatis Quadisque popu lata est. Germani usque ad Hispanias peneiraoeruni et cioitaiem nobilem Tarraconem expugnaverunl. Parihi, Mesopolamia occupata, Syriam sibi coe perunl nitulicare. Eutropius, Breuiarutn, IX, 8 With these dramatic words Eutropius and other Roman authors de scrîbed the events, which took place under the reign of the emperors Va lerian (253-260), Gallienus (253-268) and Postumus (260-269). However, the nature, the ehronologîeal and geographical spread and the impact of these invasions remain mostly unknown. The combined evidenee of texts, epigraphy, numismatics and archaeology has been proven incapable of solvîng these problems. This is why, from the beginning of the 20th cen tury, many scholars have sought a link between the Germanie invasions and the hundreds of coin hoards from this period which have been found ail over Europe e). This, in sorne cases aIl to automatically supposed, Iink between hoard and invasion has been severely critized over the last (*) Gijs DE GREEF, Kloosterstraat 58, B-3150 Haacht. -

Athenian Agora ® Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND

THE ATHENIANAGORA RESULTS OF EXCAVATIONS CONDUCTED BY THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS VOLUME II Athens COINS at FROM THE ROMAN THROUGH THE VENETIAN PERIOD BY Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. MARGARET THOMPSON License: Classical of fbj AP A J only. Ak~ use School personal American © For THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY I954 American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to The Athenian Agora ® www.jstor.org Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. License: Classical PRINTED of only. use IN School GERMANY ALL RIGHTS personal at American J.J.AUGUSTIN RESERVED © For GLOCKSTADT PREFACE Between the years 1931 and 1949 the American excavations in the Athenian Agora produced 55,492 coins of Roman and later periods. The catalogued entries in this publication, ranging in date from the last century of the Roman Republic to the declining years of the Republic of Venice, total 37,090 specimens; the remaining Islamic and Modern Greek pieces have been Athens listed summarily in order that the tally may be complete. This is an overwhelming amount of at coinage, which in sheer quantity represents a collection comparableto many in the numismatic museums of the world. Unfortunately very few of the Agora coins are museum pieces, but lamentable as is their general condition to the eye of the coin collector or the cataloguer, they do provide for the historian an invaluable record of the money circulating in one of the chief cities of from the time of Sulla to our own Studies antiquity present. -

A REASSESSMENT of GALLIENUS' REIGN TROY KENDRICK Bachelor

A REASSESSMENT OF GALLIENUS’ REIGN TROY KENDRICK Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2014 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS History Department University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Troy Kendrick, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines and reassesses the reign of the Roman emperor Gallienus in the mid-third century CE. Specifically, this paper analyses Gallienus’ military and administrative policies, his conception of his emperorship, and the influence his policies had on his successors.Gallienus ruled over the Roman Empire during a period of unprecedented calamities. The misfortunes of the Roman Empire during this period, and the biases against Gallienus in the writings of the ancient Latin authors, left a less-than-favorable impression of Gallienus’ reign. However, a re-evaluation of Gallienus and his policies unveils a remarkably capable emperor, who should be credited with not only saving the Roman Empire from complete collapse, but laying the foundation for the Empire’s recovery in the late third century CE. iii Acknowledgements I would like offer my thanks to committee members David Hay and Kevin McGeough for their assistance and comments regarding my thesis. I would especially like to thank my supervisor, Christopher Epplett, for the invaluable assistance, encouragement, and patience he has extended to me throughout the entire writing process. Finally, I would like to thank my family for -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 01:07:49PM Via Free Access MAPPING the CRISIS of the THIRD CENTURY

EPILOGUE John Nicols - 9789047420903 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 01:07:49PM via free access MAPPING THE CRISIS OF THE THIRD CENTURY John Nicols The Greek philosopher and sophist Protagoras would surely not mind this reuse of one of his most famous statements. “Concerning the crisis of the third century, I have no means of knowing whether there was one or not, or of what sort of a crisis it may have been. Many things prevent knowledge including the obscurity of the subject and the brevity of human life.”1 Within these proceedings one nds striking disagreement about whether there was a crisis as the term has been conventionally understood. And, if there was one, when did it begin? Dictionaries de ne our word crisis as: “An unstable condition, as in political, social, or economic affairs, involving an impending abrupt or decisive change”. During the years 235 to 285, the Roman Empire surely did enter a period of instability. The patterns of ‘emperor mak- ing and breaking’ and of barbarian invasion during this period mark in my estimation the characteristics of a major political crisis. Indeed, when one compares the overall stability of the Roman imperial system and government of the mid-second to that of the mid-third century, the differences are readily apparent both in terms of leadership and defense.2 In sum, that there was a ‘crisis’ is a fundamental assumption of this paper; but it is also a demonstrable proposition. I am moreover especially concerned here not only how to understand the nature of the crisis as a complex set of related events, but also how to explain the complexities of the crisis to others, especially to students. -

A Numismatic Iconographical Study of Julian the Apostate

A Revolutionary or a Man of his Time? A Numismatic Iconographical Study of Julian the Apostate Master’s Thesis in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History, Spring 2018 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Lund University Author: Nicolas Frendin Supervisor: Henrik Gerding 2 Abstract Julian the Apostate’s short rule has left in the historical records a clearly divisive picture. This thesis starts with that divisive nature of the reign of Rome’s last pagan emperor and aims to analyse some of the Apostate’s coinage iconography. Can the symbols used on the coins minted during his reign say something about his allegedly revolutionary rule? By choosing to focus on a set of ten symbols found of Julian’s coins, this thesis was subsequently divided in a three-phased analysis in order to approach the subject. Julian’s coin iconography was first analysed in comparison to the totality of the Roman Emperors, stretching back to Octavian/Augustus. The second step was to put Julian’s rule within its own context and compare his coinage iconography to that of his predecessors in his own family, the second Flavian dynasty. The last step was to observe the changes during Julian’s two periods of time in power: being first a Caesar – subordinate to his cousin Constantius II – and later on the sole ruler/Augustus. Julian’s iconography was also compared to Constantius’. The results tend to show that most of Julian’s coin iconography could be characterised as conventional. The true departures can be divided into either obvious or surprising ones. 3 Contents