Christian Tetzlaff and Lars Vogt Friday, February : Pm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

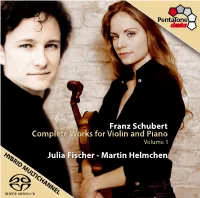

Franz Schubert Complete Works for Violin and Piano Julia

Volume 1 Franz Schubert Complete Works for Violin and Piano Julia Fischer - Martin Helmchen HYBRID MUL TICHANNEL Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) Schubert composed his Violin Sonatas Complete Works for Violin and Piano, Volume 1 in 1816, at a time in life when he was obliged he great similarity between the first to go into teaching. Actually, the main Sonata (Sonatina) for Violin and Piano in D major, D. 384 (Op. 137, No. 1) Tmovement (Allegro molto) of Franz reason was avoiding his military national 1 Allegro molto 4. 10 Schubert’s Sonata for Violin and Piano in service, rather than a genuine enthusiasm 2 Andante 4. 25 D major, D. 384 (Op. posth. 137, No. 1, dat- for the teaching profession. He dedicated 3 Allegro vivace 4. 00 ing from 1816) and the first movement of the sonatas to his brother Ferdinand, who Sonata (Sonatina) for Violin and Piano in A minor, D. 385 (Op. 137, No. 2) the Sonata for Piano and Violin in E minor, was three years older and also composed, 4 Allegro moderato 6. 48 K. 304 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart must although his real interest in life was playing 5 Andante 7. 29 have already been emphasised hundreds the organ. 6 Menuetto (Allegro) 2. 13 of times. The analogies are more than sim- One always hears that the three early 7 Allegro 4. 36 ply astonishing, they are essential – and at violin sonatas were “not yet true master- the same time, existential. Deliberately so: pieces”. Yet just a glance at the first pages of Sonata (Sonatina) for Violin and Piano in G minor, D. -

Kammermusikfest 3.–9. Juni 2013

KAMMERMUSIKFEST 3.– 9. JUNI 2013 Planungsstand: 13. März 2013 KÜNSTLERISCHE LEITUNG: LARS VOGT Liebe Kammermusikfreunde! Dear Friends of Chamber Music, Unser Hauptsponsor RWE för - A further highlight is planned dert das „Schülerkonzert“ mit 500 for 7 June: a “Night with Schu - Ein außergewöhnliches musikali - An exceptional musical program - Jugend lichen aus Schulen unserer mann”, featuring Düren author sches Programm und Künstler von me with internationally renowned Region. Dieter Kühn and three pianists. Weltruhm – dies alles er war tet Sie artists awaits you at this year‘s Als weiteres High light ist am 7. You are warmly invited to at - bei unserem diesjähri gen Kammer - Chamber Music Festival SPAN - Juni eine „Schumann-Nacht“ mit tend the public rehearsals at Haus musikfest SPANNUNGEN: Musik im NUNGEN: dem Dü rener Schrift steller Die ter Schönblick , where the music jour - RWE-Kraftwerk Heimbach. Lars Vogt and his friends will Kühn und drei Pia nisten geplant. nalist Pe dro Obiera will be holding Lars Vogt und seine Freunde be focusing in particular on early Zum Besuch der öffent lichen introductory presentations on the werden sich insbesondere mit and late works by great compo - Proben in Haus Schönblick laden concerts, and where Norbert Ely Früh- und Spätwerken großer sers to offer the public fascina - wir herzlich ein. Dort wird auch will speak on the subject ”Early Kom ponisten aus einander setzen ting insights into their works and der Musikjournalist Pedro Obie ra and Late Works – a Relation - und damit dem their development. seine Konzerteinführungen und ship”. Publikum interes - This year we are inviting three Norbert Ely einen Vortrag zum Our media part - sante Perspekti - scholarship holders: Byol Kang Thema „Frühe und späte Werke – ner, Deutschland - ven auf ihre Wer - (violin), and Danae Dörken and eine Beziehungskiste“ halten. -

September 2016 – July 2017

SEPTEMBER 2016 –JULY 2017 Director’s Introduction Frances Marshall Photography One of Britain’s foremost singers, Sarah Connolly, opens the Hall’s new season with regular duo partner Malcolm Martineau, leading listeners through a programme rich in emotional contrasts, poetic reflections and glorious melodies. The recital includes Mahler’s sublime Rückert Lieder, the impassioned lyricism of Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été, the exotic subtle narrative impressions of Debussy’s three Chansons de Bilitis, and a selection of Schumann songs. Mark Padmore’s vocal artistry and ability to extract every drop of emotion from poetic texts have secured his place among today’s finest recitalists. Morgan Szymanski, described by Classical Guitar magazine as ‘a player destined for future glories’ joins him on 12 September. Critical acclaim for Angela Hewitt’s Bach interpretations bears witness to the pianist’s extraordinary ability to connect physically and emotionally as well as intellectually with the dance rhythms and expressive gestures of the composer’s keyboard works. The Bach Odyssey will highlight all of this over the next four years. Canadian soprano Barbara Hannigan performs like a force of nature, captivating audiences with her artistry’s presence and expressive vitality. She joins the Calder Quartet, winner of the 2014 Avery Fisher Career Grant, for the world première of The sirens cycle by Peter Eötvös. Beethoven’s piano sonatas occupied forty years of his life. They offer insights into his development as artist and individual, and stand among the greatest of all his works. Igor Levit, now in his late 20s, drew critical superlatives to his debut recording of Beethoven’s late sonatas and has since established his reputation as a visionary interpreter of the composer’s music. -

Presseinformation Kronberg Academy Festival 2017

Press Release “To a new world” – the Kronberg Academy Festival 28 September – 3 October 2017 Kronberg Academy invites music lovers “to a new world”, to its festival, which will take place this year from 28 September to 3 October. International stars and top next-generation artists, who include Kronberg Academy’s young soloists, will be taking audiences on a fascinating voyage of discovery to new worlds. The violinists, viola players, cellists and pianists will be giving 21 concerts over a period of six days at eight different venues in Frankfurt and Kronberg. The concert series will be accompanied by workshops, presentations and a large exhibition with more than 20 luthiers and bowmakers as well as manufacturers of strings and accessories. Kronberg Academy’s biennial festival, launched in 1993, is a major highlight in its extensive programme of events. World-famous musicians present young soloists World-famous musicians will be presenting young soloists in joint concerts – in the 24th year since the first festival, this is still one of the unique features of the Kronberg Academy event. Members of the audience at concerts and workshops will have a close-up view of renowned artists sharing their passion for music and their experience with up-and-coming young professionals, encouraging them to expand their horizons and thus to enter new worlds. Christoph Eschenbach will set the ball rolling on 28 and 29 September, when he will take advantage of two concerts with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony in Frankfurt’s Alte Oper to present young soloists of Kronberg Academy. They will be playing works by Edward Elgar and Johannes Brahms and by Joseph Haydn, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Johannes Brahms. -

The 2021 Guide

FestivalsThe 2021 Guide April 2021 Editor’s Note Spring is in the air, vaccinations are in (many) arms, and our hardy crop of mountain, lakeside, and pastorally sited music-makers appear to be in major recovery mode from a very long, dark year. Our 2021 Festival Guide lists 100-plus entries, some still in the throes of program planning, others with their schedules nailed down, one or two strictly online, and most a combination of all of the above. We’ve asked each about their COVID-19 safety protocols, along with their usual dates, places, artists, and assorted platforms. Many are equipped to head outside: Aspen Music Festival, Tanglewood, and Caramoor Music Center already have outdoor venues. Those that don’t are finding them: Central City Opera Festival is taking Carousel and Rigoletto to a nearby Garden Center and staging Dido & Aeneas in its backyard; the Bay Chamber Concerts Screen Door Festival is headed to the Camden (ME) Amphitheater. Still others are busy constructing their own pavilions: “Glimmerglass on the Grass” is one, with 90-minute re- imagined performances of The Magic Flute, Il Trovatore, and the premiere of The Passion of Mary Cardwell Dawson. The Virginia Arts Festival has also built a new open-air facility called the Bank Street Stage, a large tent area with pod seating options. Repertoire range is as broad as ever, with the Cabrillo Festival priding itself on being “America’s longest-running festival of new orchestral music”; Bang on a Can will make as much avant-garde noise as humanly possible with its “Loud Weekend” at Mass MOCA and its composer trainings later in the summer. -

Tetzlaff Quartet Christian Tetzlaff, Violin Elisabeth Kufferath, Violin Hanna Weinmeister, Viola Tanja Tetzlaff, Cello

Sunday, November 12, 201 7, 3pm Hertz Hall tetzlaff Quartet Christian tetzlaff, violin Elisabeth Kufferath, violin Hanna weinmeister, viola tanja tetzlaff, cello PROGRAM wolfgang Amadeus MOZARt Quartet No. 16 in E-flat Major, (1756 –1791) K. 428 (K. 421b) Allegro non troppo Andante con moto Menuetto & trio Allegro vivace Alban BERG (1885 –1935) Quartet, Op. 3 Langsam Mässige Viertel INTERMISSION Franz SCHUBERt (1797 –1828) Quartet No. 15 in G Major, D. 887 Allegro molto moderato Andante un poco moto Scherzo: Allegro vivace – trio: Allegretto Allegro assai Recordings available on the CAvi Music and Ondine labels. The Tetzlaff Quartet appears by arrangement with CM Artists. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Will and Linda Schieber. Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 19 PROGRAM NOTES Quartet No. 16 in E-flat Major, eras, and by the composer himself, who insisted K. 428 (K. 421b) that the Parisian publisher Sieber pay consider - Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ably more for them than for a set of three piano Of all the famous composer pairs—Bach and concertos. “the ‘Haydn’ Quartets are models of Handel, Bruckner and Mahler, Debussy and perfection,” wrote Homer Ulrich, “not a false ges - Ravel—only Mozart and Haydn were friends. ture; not a faulty proportion. the six quartets Mozart first mentioned his acquaintance with stand as the finest examples of Mozart’s genius.” Haydn in a letter to his father on April 24, 1784, Mozart played the first three of the quartets but he probably had met the older composer (K. 387, K. -

Programmheft 2012-2013 #5 Programmheft

KonzerteIndustrie im Haus der Stadt Düren Programm 2012/2013 Vereinigte Industrieverbände von Düren, Jülich, Euskirchen und Umgebung e.V. Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe Jetzt Finanz-Check machen! Das Sparkassen-Finanzkonzept: ganzheitliche Beratung statt 08/15. Service, Sicherheit, Altersvorsorge, Vermögen. s- Sparkasse Düren Geben Sie sich nicht mit 08/15-Beratung zufrieden – machen Sie jetzt Ihren individuellen Finanz-Check bei der Sparkasse. Wann und wo immer Sie wollen, analysieren wir gemeinsam mit Ihnen Ihre finanzielle Situation und entwickeln eine maßgeschneiderte Rundum-Strategie für Ihre Zukunft. Mehr dazu in Ihrer Geschäftsstelle oder unter www.sparkasse-dueren.de. Wenn’s um Geld geht – Sparkasse. Konzerte Übersicht 2012/2013 Dienstag Junge Talente · Berlage Saxophone Quartet 4 18. September 2012 Werke von Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus 20.00 Uhr Mozart, Edvard Grieg, Erwin Schulhoff, Gioachino Rossini, Antonín Dvořák und George Gershwin Das Konzert findet statt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Bundesauswahl Konzerte Junger Künstler, einem Förderprojekt des Deutschen Musikrats. Mittwoch Südwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim 6 7. November 2012 Solist: Claus Kanngiesser (Violoncello) 20.00 Uhr Dirigent: Georg Mais Werke von Detlef Kobjela (Uraufführung), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Schubert und Joseph Haydn Konzert im Rahmen der „Mozart Wochen Eifel 2012“ Montag Severin von Eckardstein (Klavier) 8 28. Januar 2013 Werke von Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Leo Ornstein, 20.00 Uhr Ludwig van Beethoven, Nicolai Medtner und Alexander Skrjabin Konzert der Reihe „WDR 3 Kammerkonzert NRW“ Donnerstag Streichtrio Berlin 10 7. März 2013 Werke von Fritz Kreisler, Ernst von Dohnányi und 20.00 Uhr Ludwig van Beethoven Dienstag Trio „Café con Leche“ (Mandolinen / Gitarre) 12 16. April 2013 und Jasmin-Isabel Kühne (Harfe) 20.00 Uhr Konzert der Reihe "WDR 3 Kammerkonzert NRW – Open Audition Series" Ausführliche Werkeinführungen liegen vor jedem Konzert an der Abendkasse bereit. -

Booklet 305Spread.Indd

HYBRID MULTICHANNEL Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor K. 491 1 Allegro 14. 14 Cadenza: Lars Vogt 2 Larghetto 7. 37 3 Allegretto 9. 14 Piano Concerto No. 13 in C major K. 415 4 Allegro 10. 43 Cadenza: W. A. Mozart 5 Andante 9. 01 Cadenza: W. A. Mozart 6 Rondeau (Allegro) 9. 11 Martin Helmchen, piano Netherlands Chamber Orchestra Gordan Nikoli´c, Leader Recorded April 2007 at the Philharmonie, Haarlem, The Netherlands Executive / Recording Producer: Job Maarse Balance Engineer: Jean-Marie Geijsen Editing : Matthijs Ruiter Total playing time : 60. 13 The Steinway & Sons grand piano has been supplied by Ypma Piano’s Alkmaar - Amsterdam Artikel Ronald Vermeulen und Biographien auf Deutsch und Französisch finden Sie auf unseren Webseite. Pour les versions allemande et française des biographies et l’essai de Ronald Vermeulen, veuillez consulter notre site. www.pentatonemusic.com Mozart’s Piano Concertos special thanks to PentaTone for grant- K.491 and K.415 ing me the extraordinary freedom, from the start, of recording the reper- hen I asked Job Maarse in toire that means most to me artistically WFebruary what he had in mind at that moment. for our first CD, he replied as follows: Why did I happen to choose pre- “Why not two Mozart concertos?”. cisely these two concertos, given I was immediately enthusiastic, as the choice of the entire marvel- I just happened to be – and still am lous universe of Mozart concertos? – in a “Mozart” phase. But my next Mozart’s piano concertos are a part thought was: would it not be better of every pianist’s life, from a young to select something more unusual for age onwards, and the Piano Concerto a solo début CD? For instance, reper- in C, K.415 was the first piece that I toire to really make people sit up and was allowed to play with an orches- notice? After all, Mozart again, right tra as a child. -

Martin Helmchen

Franz Schubert Complete Works for Violin and Piano Volume 2 Fantasy for piano duet, D. 940 Julia Fischer - Martin Helmchen Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) the music-historian Guido Fischer described Schubert’s Fantasia for Violin Complete Works for Violin and Piano, Volume 2 and Piano in C major, D. 934 (Op. posth. 159), written one year before the Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major “Duo”, D. 574 (Op. posth. 162) chubert concluded his personal violin sonata ‘chapter’ early on, as death of the composer, as “a model of cheerful nonchalance and playful 1 Allegro moderato 8. 52 Shis last work in this genre dates from 1817: the Sonata for Violin this-worldliness”? For although the Fantasia is light and easy-going, spar- 2 Scherzo (Presto) 4. 08 and Piano in A major, D. 574 (Op. posth. 162, Grand Duo). Perhaps he kling and, as far as I’m concerned, ‘this-worldly’ in its fast sections, at the 3 Andantino 4. 28 put aside any further plans for violin sonatas he might have had due to beginning this piece is anything but this-worldly: rather, it is introverted 4 Allegro vivace 4. 57 a number of significant experiences he underwent in 1817. Although in more radical a manner than one usually comes across in music from Fantasia for Violin and Piano in C major, D. 934 (Op. posth. 159) Schubert is often portrayed by the lay world as never being successful Schubert’s time. For already at the solemn moment of the beginning, 5 Andante molto 3. -

Christian Tetzlaff, Violin and Lars Vogt, Piano

Da Camera Sarah Rothenberg Pre-concert conversation with artistic and general director Christian Tetzlaff, Lars Vogt and Sarah Rothenberg Cullen Theater, 7:15 PM Cullen Theater, Wortham Theater Center Thursday, February 16, 2017; 8:00 PM Christian Tetzlaff, violin and Lars Vogt, piano Ludwig van Beethoven Sonata No. 7 in C Minor, Op. 30, No. 2 (1801-02) (1770-1827) Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Scherzo. Allegro Finale: Allegro - Presto Béla Bartók Sonata for Violin and Piano, No. 2, Sz. 76 (1922) (1881-1945) Molto moderato Allegretto INTERMISSION Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for Piano and Violin in F Major, K. 377 (1781) (1756-1791) Allegro Tema con variazioni. Andante Tempo di menuetto, un poco allegretto Franz Schubert Rondo in B Minor, D. 895 (1826) (1797-1828) Andante Allegro - Più mosso This performance is sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts. This event is the inaugural James K. Schooler Memorial Concert, an annual event recognizing the generous bequest made by a loyal Da Camera subscriber and donor. 24 Beethoven: Sonata No. 7 for Violin and panse banters with surprising rhyth- tery rather than grounding the music Piano in C Minor, Op. 30, No. 2 mic contrasts and even dresses up its on an easily perceived tonic (although Trio section with an unanticipated the composer insisted that the Second When he wrote his three Op. 30 canon between the violin and the pia- Sonata was basically in C Major). violin sonatas, in 1802, Ludwig van no’s left-hand part. The Finale is as ex- This work also reveals glimpses Beethoven was on the verge of his citing as the Scherzo is wry. -

Kammermusikfest 23.–30. Juni 2019

VON FREMDEN LÄNDERN UND MENSCHEN KÜNSTLERISCHE LEITUNG: LARS VOGT KAMMERMUSIKFEST 23.–30. JUNI 2019 SCHIRMHERR: MINISTERPRÄSIDENT ARMIN LASCHET VON FREMDEN LÄNDERN UND MENSCHEN ist der Titel des ersten Stückes aus Robert Schumanns Die Auftragskomposition stammt von dem französischen „Kinderszenen“. So lautet auch das Motto unseres dies- Komponisten Éric Montalbetti. jährigen Kammermusikfestes. Unter dem Titel SOLO präsentieren wir am Samstag, den Die romantische Poesie ist spätestens seit Novalis und ande- 22. Juni erstmalig im Vorprogramm ein Konzert, bei dem ren geprägt von der tiefen Sehnsucht nach dem Frem den, unsere Musiker ausschließlich Solostücke für ihr Instru- nach unbekannten fernen Welten, Abenteuerlust, Suche und ment darbieten. Neugier. Und natürlich gehört auch wieder klassische Kammermusik Beim Hören des Klavierstückes von Schumann fällt uns von Beethoven, Brahms, Haydn, Mozart und Schubert zum die Assoziation zu diesen Themen sehr leicht, auch wenn Programm. es die unterschiedlichs- Unser „Jugendprogramm“ nimmt einen breiten Raum ein: ten Interpretationen und Neben den zwei Stipendien vergeben wir zwei Schülerprei- Analysen dazu gibt, was se, veranstalten ein Schülerkonzert mit Malte Arkona und sich Schumann bei diesem einen Jugend-Workshop mit Pedro Obiera. Ein Vortrag des Titel gedacht haben könn- Schriftstellers Karl-Heinz te. In jedem Fall empfin- Ott und die beliebten Kon- den wir die einfache und zerteinführungen mit Pedro Foto: © Anna Reszniak einprägsame Melodie als Obiera stehen ebenfalls auf leicht und beschwingt, jedoch niemals als bedrohlich oder dem Programm. (Info und angsteinflößend. Termine s. Seite 10). Das allem Fremden neugierig und suchend zugewandte Ge- Die öffentlichen Proben fin- fühl der Romantik hat sich in den letzten 200 Jahren durch den auf Burg Hengebach in die Folgen der Kolonialzeit, insbesondere aber im Rahmen den Räumlichkeiten der dortigen Kunstakademie statt. -

Franz Schubert Complete Works for Violin and Piano Julia

Franz Schubert HYBRID MUL Complete Works for Violin and Piano Volume 2 TICHANNEL Fantasy for piano duet, D. 940 Julia Fischer - Martin Helmchen Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) himself, and he put an end to his compo- Complete Works for Violin and Piano, Volume 2 sition lessons with Antonio Salieri. In this chubert concluded his personal violin period of time, Schubert also wrote two Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major “Duo”, D. 574 (Op. posth. 162) Ssonata ‘chapter’ early on, as his last work of his most famous songs: Der Tod und das 1 Allegro moderato 8. 52 in this genre dates from 1817: the Sonata Mädchen (= Death and the maiden) and Der 2 Scherzo (Presto) 4. 08 for Violin and Piano in A major, D. 574 (Op. Wanderer (= The wanderer). Two successes 3 Andantino 4. 28 posth. 162, Grand Duo). Perhaps he put in the Lied genre, which led to the contact 4 Allegro vivace 4. 57 aside any further plans for violin sonatas with the baritone Johann Michael Vogl, he might have had due to a number of sig- who would later become one of his most Fantasia for Violin and Piano in C major, D. 934 (Op. posth. 159) nificant experiences he underwent in 1817. important friends and patrons. On the other 5 Andante molto 3. 22 Although Schubert is often portrayed by side, the lack of funds, with which Schubert 6 Allegretto 5. 36 the lay world as never being successful had struggled since resigning from his job 7 Andantino 10.