Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fear and Loathing Inby Kjetil Duvold Lithuania & Inga Aalia Illustration Karin Sunvisson

40 essay FEAR AND LOATHING INby Kjetil Duvold LITHUANIA & Inga Aalia illustration Karin Sunvisson n March 11, 2010, one of Lithuania’s three na- the Lithuanian political and cultural establishment sought against homosexuality among the population. In 2007 and tional holidays, an annual march of radical to demonstrate that this mixture was compatible, comple- 2008, Vilnius gained notoriety as the only European capital nationalists took place in the heart of Vilnius mentary and even necessary; “Europeanness” was invoked which did not grant permission to park the European Com- with an official permit from the municipality. as a core argument for Lithuania’s prompt inclusion in the mission’s campaign truck “For Diversity — Against Discrimina- Although rather low-key compared with the infamous march European Union. After accession to the EU in 2004, however, tion” in the city center. Kaunas, Lithuania’s second city, made of 2008, when participants chanted openly racist and anti- a more cynical attitude to European integration arose. The la- a similar decision in 2008. Citing safety arguments, the may- Semitic slogans, the march nonetheless retained its unmistak- bels “Lithuanian” and “European” are no longer assumed to ors of Vilnius and Kaunas nonetheless made such statements able ultra-nationalist feel, and slogans such as “Lithuania for be complementary. Many of the country’s leading politicians as, “There will be no advertising for sexual minorities”, and Lithuanians” were hardly more palatable. That did not seem and social personalities are to an increasing extent portraying “Tolerance has its limits”.2 In a separate incident, trolleybuses to faze the protagonists, including a parliamentarian from the the “liberal European agenda” as antithetical and even threat- in Vilnius and Kaunas carrying awareness campaign messages Homeland Union party who had applied for the municipal ening to “traditional Lithuanian values”. -

Please Download Issue 2 2012 Here

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. June 2012. Vol. V:2. 1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Academic life in newly Södertörn University, Stockholm founded Baltic States BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com LANGUAGE &GYÖR LITERATUREGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG GYÖRGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG also in this issue ILL. LARS RODVALDR SIBERIA-EXILES / SOUNDPOETRY / SREBRENICA / HISTORY-WRITING IN BULGARIA / HOMOSEXUAL RIGHTS / RUSSIAN ORPHANAGES articles2 editors’ column Person, myth, and memory. Turbulence The making of Raoul Wallenberg and normality IN auGusT, the 100-year anniversary of seek to explain what it The European spring of Raoul Wallenberg’s birth will be celebrated. is that makes someone 2012 has been turbulent The man with the mission of protect- ready to face extraordinary and far from “normal”, at ing the persecuted Jewish population in challenges; the culture- least when it comes to Hungary in final phases of World War II has theoretical analyzes of certain Western Euro- become one of the most famous Swedes myth, monuments, and pean exemplary states, of the 20th century. There seem to have heroes – here, the use of affected as they are by debt been two decisive factors in Wallenberg’s history and the need for crises, currency concerns, astonishing fame, and both came into play moral exemplars become extraordinary political around the same time, towards the end of themselves the core of the solutions, and growing the 1970s. The Holocaust had suddenly analysis. public support for extremist become the focus of interest for the mass Finally: the historical political parties. -

Ethnography of Voting: Nostalgia, Subjectivity, and Popular Politics in Post-Socialist Lithuania

ETHNOGRAPHY OF VOTING: NOSTALGIA, SUBJECTIVITY, AND POPULAR POLITICS IN POST-SOCIALIST LITHUANIA by Neringa Klumbytė BA, Vytautas Magnus University, 1996 MA, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1997 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented By Neringa Klumbytė It was defended on March 31, 2006 and approved by Nicole Constable, Professor, Department of Anthropology Ilya Prizel, Professor, UCIS Alberta Sbragia, Professor, Department of Political Science Andrew Strathern, Professor, Department of Anthropology ii ETHNOGRAPHY OF VOTING: NOSTALGIA, SUBJECTIVITY, AND POPULAR POLITICS IN POST-SOCIALIST LITHUANIA Neringa Klumbytė, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Politics in Eastern Europe has become increasingly defined by apparent paradoxes, such as majority voting for the ex-communist parties in the early 1990s and strong support for populists and the radical right later in the 1990s and 2000s. The tendency in political science studies is to speak about the losers of transition, and to explain success of the ex-communist, radical and populist parties and politicians in terms of the politics of resentment or protest voting. However, what subjectivities have been produced during post-socialism and why/how they are articulated in particular dialogues among politicians and people, are questions that have not been discussed in most studies. In this dissertation I explore political subjectivities to explain voting behavior in the period of 2003-2004 in Lithuania. I analyze nostalgia for socialism and individuals’ relations to social and political history, community, nation, and the state. -

Lėlių Kambariai

28 Straipsnio publikaciją parėmė Daiva ŠABASEVIČIENĖ LĖLIŲ KAMBARIAI CHAMBERS OF DOLLS An exhibition to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the founding of the oldest international theatre organisation, the UNIMA union of puppeteers (Union Internationale de la Marionette) called ‘X/S studentų lėlių teatrai’ (X/S Student Puppet Theatres) was held at the Lithuanian Theatre, Music and Cinema Museum from 5 December to 15 February. Founded in 1930 in Prague, UNIMA is the oldest international theatre organisation in the world, and has sections in 70 different countries on all continents (the Lithuanian UNIMA centre was founded in 2004). The exhibition shows exhibits from the revived student theatre Šėpa (1988–1992) at the Lithuanian State Conservatoire (now the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre), the puppet theatre (c. 1929) and the shadow theatre (c. 1946) at the Šiauliai Teacher Training College, the puppet theatre at the Vilnius Tekhnikum library (1956–1957), the puppet theatre (1947–1952) and the theatre Ū (1989–1993) at the Vilnius Art Institute, and the puppet theatre Trupė 459 (Troupe 459), originally founded at Klaipėda University but now independent. The exhibition was curated by Rimas Driežis and coordinated by Aušra Endrukaitienė. The artist was Irma Balakauskaitė. This analysis of the exhibition is by Daiva ŠABASEVIČIENĖ. Lietuvos teatro, muzikos ir kino muziejuje veikusi pa Surengti gerą teatrinę parodą – daug sudėtingiau nei pa roda „XS / studentų lėlių teatrai“ – natūraliai susiformavusio statyti gerą spektaklį. Pirmiausia dėl to, jog tam reikia ypa ciklo, skirto lėlininkų menui, dalis. Dar 2018 metų pabaigo tingai daug laiko ir susitelkimo. Paroda galerijoje „Arka“ je Lietuvos dailininkų sąjungos galerijoje „Arka“ lėlininko surengta bendradarbiaujant su visais Lietuvos muziejais, Rimo Driežio ir teatro „Lėlė“ pastangomis buvo atidaryta kolekcininkais, privačiais asmenimis, teatrais. -

Rinkiminis Laikr 20.Pmd

Vyriausiosios rinkimø komisijos Pasirinkimas informacinis leidinys Seimo rinkimai 2008 spalio 12 dienà www.vrk.lt Kodël balsuosiu Seimo rinkimuose? Leidinys Tau, rinkëjau Po Lietuvos Nepriklausomybës atkûrimo 1990-øjø kovo 11-àjà, Jûs, gerbiamieji rinkëjai, rink- site jau penktàjá ðalies Seimà. Ðalies Konstitucijos 2-asis straipsnis sako: „Lietuvos valsty- bæ kuria Tauta. Suverenitetas priklauso Tautai“. Mes siûlome jà, Lietuvos valstybæ, ið tiesø kurti. Viliamës, kad Jûs, mielieji rinkëjai, iðreikðite savo valià spalio 12 dienà rengiamuose Seimo rinkimuose. Raginame Jus susipaþinti ir panagrinëti politiniø partijø, jø kandidatø programas bei nuostatas. Specialiai ðiems Seimo rinki- mams skirtas leidinys „Pasirinki- mas 2008“. ELTOS nuotr. Prie rinkimø balsadëþës susitiks skirtingø kartø atstovai. Jø balsai lems, kurie politikai pasidalys 141 vietà Seime. Tada supratau, kaip svarbu turëti Noriu, kad ðiuose rinkimuose bûtø at- pasirinkimo laisvæ. Dabar mes jà turi- spindëta ir mano nuomonë. me. Ir tai reikëtø vertinti. Jei mes, rinkëjai, bûsime pasyvûs, tu- Að savo mokiniø daþnai klausiu – rësime taikstytis su kitø sprendimu, kitø Faustas kam priklauso aukðèiausioji valdþia Lie- iðrinktais valdþios atstovais. Nesuprantu Meðkuotis, tuvoje? Jie man sako: Prezidentui, Vy- þmoniø, kurie keikia valdþià, nors rinki- 41 metø gimnazijos riausybei, Seimui. Tada að pasiûlau pa- Justinas muose nebalsuoja. Tikiu, kad galima pa- istorijos, þvelgti á Lietuvos Respublikos Konsti- Galinis, siekti teigiamø permainø. pilietiðkumo tucijà. 2-ajame straipsnyje aiðkiai pa- 21 metø mokytojas raðyta, kad Lietuvos valstybæ kuria Tau- studentas ta, suverenitetas priklauso Tautai. SKAIÈIUS: “Kai buvau 19 metø jaunuolis, tar- Taigi aukðèiausioji valdþia ðiandien “Manau, iðreikðti savo pilietinæ po- navau sovietø armijoje Kazachstane. priklauso bûtent mums, ðalies pilie- zicijà – bûtina. Planuoju pasiskaityti 2 mln. -

NATO OPEN DOOR: TEN YEARS AFTER the “BIG BANG” Vilnius, Lithuania 3-4 April 2014

NATO OPEN DOOR: TEN YEARS AFTER THE “BIG BANG” VILNIUS, LITHUANIA 3-4 APRIL 2014 Hosted by: PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA DALIA GRYBAUSKAITĖ Organized by: G NER Y SE E CU O R T I A T Y N C E E C N N T E R L E O EL F EXC CENTRE FOR GEOPOLITICAL STUDIES MINISTRY OF NATIONAL DEFENCE OF LITHUANIA GENERAL INFORMATION VENUE The Vilnius Conference 2014 will take place in the Office of the President of the Republic of Lithuania S. Daukanto a. 3, LT-01122 Vilnius. HOTELS Artis Centrum Hotel Narutis Hotel Liejyklos Str. 11/23, Pilies Str. 24, LT-01120 Vilnius, Lithuania; LT-01123 Vilnius, Lithuania; +370 52660366 +370 52122894 Kempinski Hotel Cathedral Square Novotel Vilnius Hotel Universiteto Str. 14, Gedimino av. 16, LT-01122 Vilnius, Lithuania; LT-01103 Vilnius, Lithuania; +370 5221100 +370 52666200 Amberton Hotel Radisson Blu Astorija Hotel L. Stuokos-Gucevičiaus Str. 1, Didžioji Str. 35, LT-01122 Vilnius, Lithuania; LT-01128 Vilnius, Lithuania; +370 52107461 +370 5212 0110 SECURITY Foreign nationals are advised to have their photo ID throughout the whole span of the visit. You will be asked to show your ID at the entrance to the venue of the Vilnius conference. The organizers would appreciate if you wear your conference badge/pin thourghout the whole conference. In case of emergency, please call emergency line – 112. TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 CONTACT PERSONS 5 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS 6 PROGRAMME 8 SPEAKERS OF THE ACADEMIC SESSIONS 3 CONTACT PERSONS These persons are ready to help in case of any uncertainties: Ms. -

Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States

Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States Edited by Tony Lawrence Tomas Jermalavičius 1 Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States Edited by Tony Lawrence Tomas Jermalavičius International Centre for Defence Studies Toom-Rüütli 12-6 Tallinn 10130 Estonia Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States Edited by Tony Lawrence Tomas Jermalavičius © International Centre for Defence Studies Tallinn, 2013 ISBN: 978-9949-9174-7-1 ISBN: 978-9949-9174-9-5 (PDF) ISBN: 978-9949-9174-8-8 (e-pub) ISBN 978-9949-9448-0-4 (Kindle) Design: Kristjan Mändmaa Layout and cover design: Moonika Maidre Printed: Print House OÜ Cover photograph: Flag dedication ceremony of the Baltic Peacekeeping Battalion, Ādaži, Latvia, January 1995. Courtesy of Kalev Koidumäe. Contents 5 Foreword 7 About the Contributors 9 Introduction Tomas Jermalavičius and Tony Lawrence 13 The Evolution of Baltic Security and Defence Strategies Erik Männik 45 The Baltic Quest to the West: From Total Defence to ‘Smart Defence’ (and Back?) Kęstutis Paulauskas 85 The Development of Military Cultures Holger Mölder 122 Supreme Command and Control of the Armed Forces: the Roles of Presidents, Parliaments, Governments, Ministries of Defence and Chiefs of Defence Sintija Oškalne 168 Financing Defence Kristīne Rudzīte-Stejskala 202 Participation in International Military Operations Piret Paljak 240 Baltic Military Cooperative Projects: a Record of Success Pete Ito 276 Conclusions Tony Lawrence and Tomas Jermalavičius 4 General Sir Garry Johnson Foreword The swift and total collapse of the Soviet Union may still be viewed by some in Russia as a disaster, but to those released from foreign dominance it brought freedom, hope, and a new awakening. -

Seminar on the Participatory Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe Today: Challenges and Perspectives

Seminar on the Participatory democracy in central and eastern Europe today: challenges and perspectives p r o c e e d i n g s Vilnius, 3-5 July 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. OPENING SESSION Mr Gunnar JANSSON, Chair of the Committee on Parliamentary and Public relations of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe............................................................................................................... 5 Welcoming address by Mr Vytautas LANDSBERGIS, Speaker of the Lithuanian Parliament ............................................................................... 6 Introduction by Mr Andreas GROSS, Member of the National Council (Switzerland), General Rapporteur of the Committee on Parliamentary and Public Relations of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe..................................................................................................... 7 II.WORKING SESSION I ........................................................................................................... 9 Theme I: Participatory democracy in the Baltic States, before and after the communist regime Rapporteur: Mr Henn-Jüri UIBOPUU, Professor at the University of Salzburg, Tallinn (Estonia).................................................................... 9 Observations : Mr Rimantas DAGYS, Vice-Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Lithuanian Seimas ...................................................... 11 Mr Tunne KELAM, Deputy Speaker of the Riigikogu (Estonia), Vice-Chair of the Committee on Parliamentary -

General Elections in Lithuania on 11 and 25 October

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN LITHUANIA 11-25TH OCTOBER 2020 European The Farmers and Greens Party Elections monitor (LVZS), led by outgoing Prime Corinne Deloy Minister Saulius Skvernelis, could remain in office after the general election in Lithuania ANALYSIS At the beginning of April, while Lithuanians were in Political observers expect little change in the voting on lockdown the President of the Republic Gitanas Nauseda October 11 and 25. They anticipate that negotiations announced that his fellow-citizens would be called to over a future governing coalition will be lengthy. It could ballot on October 11 and 25 to renew the 141 elected also be unstable. MPs of the Seimas, the only house of parliament. 22 According to the latest opinion poll conducted by the political parties are competing in these parliamentary Spinter Tyrimai Institute, the Homeland Union-Christian elections, 332 people, including 282 affiliated to a Democrats (TS-LKD), the main opposition party led by party and 38 who are running as independents, are Gabrielius Landsbergis, is due to come out ahead with candidates. 21.7% of the vote. It is expected to be followed by the Farmers and Greens Party with 19.4%, the Social Lithuania is governed by a coalition government led by Democratic Party with 12.6%, and the Labour Party Prime Minister Saulius Skvernelis, which includes the with 8.6%, followed by the Freedom Party (Laisves), a LVZS and the Social Democratic Labour Party (LSDDP) social-liberal party led by Ausrinė Armonaite with 6.8% of Gediminas Kirkilas. The government is supported and the Liberal Movement (LRLS) of Eugenijus Gentvilas by “Welfare Lithuania” and the Electoral Action for with 5.9%. -

Debate in Lithuania on EU Expansion to East: the Case of Turkey

93 Egdûnas Raèius* Institute of International Relations and Political Science of the University of Vilnius Lithuanian Military Academy Debate in Lithuania on EU Expansion to East: the Case of Turkey Although Turkey has been knocking on the EUs gates for almost four decades, only the echo of that knock was being heard in Lithuania until 2004. After Lithuania joined the EU, the question of Turkish membership in the EU was by design added to the agenda of the Lithuanian governments foreign policy. High-ranking state officials rushed to assure both citizens and the world that Lithuania supports the objectives of Turkey, whereas opposition (rightist) parties expressed concern about the lack of debate on this issue in the Parliament, the government and society in general. The opinion of the society, to which the Lithuanian government had not yet appealed in any way, is not clear yet. Political analysts and journalists writing on this issue tend to demonize Turkey and practically frighten the general public. It seems that a passi- vely negative mood is settling over ordinary citizens, which in the case of referendum can become potential Nos to the Turkish membership in the Bloc. Introduction In this article the author analyzes discussions in the Lithuanian public discourse on possible Turkish entrance into the EU with the purpose to find out opinions and positions of separate groups of society. The approach to the pro- blem is both political and public. The political approach includes speeches of top politicians and statements of some parties, MPs and members of the Europe- an Parliament on the issue of Turkey. -

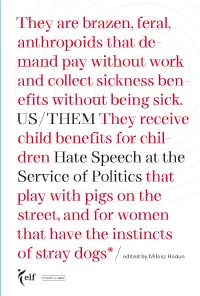

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

Pasipriešinimo Istorijos Programos

PASIPRIEŠINIMO ISTORIJOS PROGRAMOS PRIEDAI 1 REKOMENDUOJAMOS LITERATŪROS SĄRAŠAS BENDRIEJI KLAUSIMAI Amerikos lietuvių istorija (redaktorius A. Kučas). Boston, Mass. 1971 (temos apie pokario imigrantus, jų organizacijas ir pan.). Antikomunistinis kongresas ir tribunolo procesas. Komunizmo nusikaltimo įvertinimas 2000. V., 2002. Dokumentų rinkinys. XX amžius. Mokymo priemonė / Sudarė Kasperavičius, A., Manelis, E., Sindaravičius A. V., 2002. Genocidas ir rezistencija. Mokslinis žurnalas leidžiamas LGRTC nuo 1997 m. du kartus per metus (išleisti 27 numeriai). Į Laisvę. Rezistencinės minties periodinis žurnalas leidžiamas LFB organizacijos ir „Į LAISVĘ“ fondo lietuviškai kultūrai ugdyti (nuo 1953 iki 2000 m. JAV, nuo 2000 m. – Lietuvoje). Kiaupa Z. Lietuvos valstybės istorija. V., 2004; 2005 (lietuvių ir anglų k.) Laisvės kovų archyvas. Periodinis leidinys laisvės kovų tematika leidžiamas LPKTS nuo 1991 (išleisti 34 numeriai). Lietuva 1009-2009. Sudarė A. Butrimas, R. Janonienė, T. Račiūnaitė. Vilnius, 2009. Lietuva 1940-1990: okupuotos Lietuvos istorija. Vilnius, 2005. II pat. ir papild. leid. V., 2007. Lietuvos istorija. Enciklopedinis žinynas. Sudarė E. Manelis ir A. Račis. Vilnius, 2011. T.1. A-K. Lietuvos istorija. Vilnius, Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas, 2010. (straipsniai iš VLE) Lietuvos istorijos chrestomatija, 1861 - 1990 03 11 / Sudarė A. Gaigalaitė, J. Skirius. K., 1993. Lietuvių švietimas Vokietijoje (redaktorius V. Čiulevičius). Chicago, 1969 (temos apie švietimą ir mokyklas DP stovyklose). Vilniaus tribunolo nuosprendis (2000), V., 2001. ŠALTINIAI IR TYRINĖJIMAI Abromavičius, S. Žalio velnio takais. K., 1995. Abromavičius, S. Didžiosios Kovos apygardos partizanai. K., 2007. Abromavičius, S. Gyvenkit laisvi ir laimingi: Apie Tito Masiulio gyvenimą ir žygdarbį. K., 2005. Abromavičius, S. Partizanų motinos: [esė]. K., 2010. Abromavičius, S. Ir kt. Didžiosios kovos apygardos partizanai.