Please Download Issue 2 2012 Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust

Ezra’s Archives | 77 Strategies of Survival: Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust Taly Matiteyahu On the eve of World War II, Lithuanian Jewry numbered approximately 220,000. In June 1941, the war between Germany and the Soviet Union began. Within days, Germany had occupied the entirety of Lithuania. By the end of 1941, only about 43,500 Lithuanian Jews (19.7 percent of the prewar population) remained alive, the majority of whom were kept in four ghettos (Vilnius, Kaunas, Siauliai, Svencionys). Of these 43,500 Jews, approximately 13,000 survived the war. Ultimately, it is estimated that 94 percent of Lithuanian Jewry died during the Holocaust, a percentage higher than in any other occupied Eastern European country.1 Stories of Lithuanian towns and the manner in which Lithuanian Jews responded to the genocide have been overlooked as the perpetrator- focused version of history examines only the consequences of the Holocaust. Through a study utilizing both historical analysis and testimonial information, I seek to reconstruct the histories of Lithuanian Jewish communities of smaller towns to further understand the survival strategies of their inhabitants. I examined a variety of sources, ranging from scholarly studies to government-issued pamphlets, written testimonies and video testimonials. My project centers on a collection of 1 Population estimates for Lithuanian Jews range from 200,000 to 250,000, percentages of those killed during Nazi occupation range from 90 percent to 95 percent, and approximations of the number of survivors range from 8,000 to 20,000. Here I use estimates provided by Dov Levin, a prominent international scholar of Eastern European Jewish history, in the Introduction to Preserving Our Litvak Heritage: A History of 31 Jewish Communities in Lithuania. -

European Parliament 2019-2024

European Parliament 2019-2024 Committee on Industry, Research and Energy ITRE_PV(2019)0925_1 MINUTES Meeting of 25 September 2019, 9.00-12.30 and 14.30-18.30 BRUSSELS 25 September 2019, 9.00 – 10.00 In camera 1. Coordinators’ meeting The Coordinators’ meeting was held from 9.00 to 10.00 in camera with Adina-Ioana Vălean (Chair) in the chair. (See Annex I) * * * The meeting opened at 10.04 on Wednesday, 25 September 2019, with Adina-Ioana Vălean (Chair) presiding. 2. Adoption of agenda The agenda was adopted. PV\1189744EN.docx PE641.355 EN United in diversityEN 3. Chair’s announcements Chair’s announcements concerning coordinators’ decisions of 3 September 2019. Chair has informed the Committee members that the Committee meeting of 7-8 October has been cancelled due to the Commissioner hearing. The next ITRE Committee meeting will take place on the 17 October 2019. 4. Approval of minutes of meetings 2-3 September 2019 PV – PE641.070v01-00 The minutes were approved. *** Electronic vote *** 5. Establishing the European Cybersecurity Industrial, Technology and Research Competence Centre and the Network of National Coordination Centres ITRE/9/01206 ***I 2018/0328(COD) COM(2018)0630 – C8-0404/2018 Rapporteur: Rasmus Andresen (Verts/ALE) Responsible: ITRE Vote on the decision to enter into interinstitutional negotiations The decision to enter into interinstitutional negotiations was adopted: for: 49; against: 12; abstention: 2. (Due to technical issues, roll-call page is not available) 6. Labelling of tyres with respect to fuel efficiency and other essential parameters ITRE/9/01207 ***I 2018/0148(COD) COM(2018)0296 – C8-0190/2018 Rapporteur: Michał Boni Responsible: ITRE Vote on the decision to enter into interinstitutional negotiations The decision to enter into interinstitutional negotiations was adopted: for: 56; against: 3; abstention: 4. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 194

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194 Jessica Giandomenico Transformative Power Challenged EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Brusewitzsalen, Gamla Torget 6, Uppsala, Saturday, 19 December 2015 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor David Phinnemore. Abstract Giandomenico, J. 2015. Transformative Power Challenged. EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited. Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194. 237 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554-9403-2. The EU is assumed to have a strong top-down transformative power over the states applying for membership. But despite intensive research on the EU membership conditionality, the transformative power of the EU in itself has been left curiously understudied. This thesis seeks to change that, and suggests a model based on relational power to analyse and understand how the transformative power is seemingly weaker in the Western Balkans than in Central and Eastern Europe. This thesis shows that the transformative power of the EU is not static but changes over time, based on the relationship between the EU and the applicant states, rather than on power resources. This relationship is affected by a number of factors derived from both the EU itself and on factors in the applicant states. As the relationship changes over time, countries and even issues, the transformative power changes with it. The EU is caught in a path dependent like pattern, defined by both previous commitments and the built up foreign policy role as a normative power, and on the nature of the decision making procedures. -

Habaneros from My Backyard Garden Infused This Vodka with a Glassy Golden Hue

More Edge Than Edgy by Barbara Haas appeared in The Isthmus Review, 2019 Habaneros from my backyard garden infused this vodka with a glassy golden hue. I angled the bottle toward the window, tilting it just-so. Plenty of sunshine streamed through. I had whipped this batch up from Belaya Berezka, a premium brand I had brought back from Moscow last month. My homespun recipe called for a ratio of three habaneros to one liter. When I sliced the peppers, a vapor wave of pungent heat wafted up and engulfed me. I even recoiled somewhat, because the skin around my nose suddenly tingled. The peppers were richly pigmented inside and out—zesty, orange and bright—and my knife left bold fiery streaks on the cutting board. On the day I sieved the vodka and filtered it through a fine mesh cloth, nothing about the spent slices or seeds said “habanero” any longer. Three weeks in a cool dark place allowed Scoville Units to transfer massively to the vodka. A 40% alcohol content had performed a Total Takedown on the habaneros. The exchange between the two had been supreme. When I flew back from Moscow last month, this liter of Belaya Berezka was crystalline and clear. It had now acquired a striking amber glow but remained as transparent as glass. I stood the bottle in the freezer all afternoon and then later that evening downed a shot “in one,” as my Muscovite komradski might say. Cold and spicy at the same time, this vodka would torch a Bloody Mary to perfection. -

Estonia Economy Briefing: Wrapping the Year Up: in Search for a Productive Economic Reform E-MAP Foundation MTÜ

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 35, No. 2 (EE) December 2020 Estonia economy briefing: Wrapping the year up: in search for a productive economic reform E-MAP Foundation MTÜ 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: CHen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 Wrapping the year up: in search for a productive economic reform When your country’s economy is reasonably small but, to an extent, diverse, even a major crisis would not seem to be too problematic. Another story is when the pandemic substitutes ‘a major crisis’ – then there may be a dual problem of analysing the present and forecasting the future. In one of his main interviews (if not the main one), which was supposed to be wrapping the difficult year up, Estonian Prime Minister Jüri Ratas was into memorable metaphors when it would come to pure politics, but distinctly shy when a question was on economics1. During 2020, in political terms, the country was getting involved into discussing way more intra- political scandals than it would have been necessary to test the ‘health’ of a democracy. As for the process of running the economy, apart from borrowing more to survive the pandemic, the only major economic reform that the current governmental coalition managed to ‘squeeze’ through the ‘hurdles’ of the Riigikogu’s passing and the presidential approval was the so-called second pillar pension reform. The idea of the Government was to respond to a particular societal call that was, in a way, ‘inspired’ by Pro Patria and some other proponents of the prospective reform. -

Annual Report of the Chancello

Dear reader, In accordance with section 4 of the Chancellor of Justice Act, the Chancellor has to submit an annual report of his activities to the Riigikogu. The present overview of the conformity of legislation of general application with the Constitution and the laws covers the period from 1 June until 31 December 2004, and the outline of activities concerning the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms of persons, the period from 1 January until 31 December 2004. The overview contains summaries of the main cases that were settled as well as generalisations of the legal problems and difficulties, together with proposals on how to improve the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms and how to raise the quality of law making. The readers will also be able to familiarise themselves with the organisation of work in the Office of the Chancellor of Justice. According to the Constitution, the Chancellor of Justice is an independent constitutional institution. Such a status enables him to assess problems objectively and to protect people effectively from arbitrary measures of the state authority. One tool for fulfilling this task is the opportunity that the Chancellor of Justice has to submit to the Riigikogu his conclusions and considerations regarding shortcomings in legislation, in order to contribute to strengthening the principles of democracy and the rule of law. I am grateful to the members of the Riigikogu and its committees, in particular the Constitutional Committee, the Legal Affairs Committee and the Social Affairs Committee, for having been open to mutual, trustful and effective cooperation, which will hopefully continue just as fruitfully in the future. -

Conde, Jonathan (2018) an Examination of Lithuania's Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation

Conde, Jonathan (2018) An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Masters thesis, York St John University. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/3522/ Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Research MA History at York St John University School of Humanities, Religion & Philosophy by Jonathan William Conde Student Number: 090002177 April 2018 I confirm that the work submitted is my own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the works of others. This copy has been submitted on the understanding that it is copyright material. Any reuse must comply with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and any licence under which this copy is released. @2018 York St John University and Jonathan William Conde The right of Jonathan William Conde to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Acknowledgments My gratitude for assisting with this project must go to my wife, her parents, wider family, and friends in Lithuania, and all the people of interest who I interviewed between the autumn of 2014 and winter 2017. -

Fear and Loathing Inby Kjetil Duvold Lithuania & Inga Aalia Illustration Karin Sunvisson

40 essay FEAR AND LOATHING INby Kjetil Duvold LITHUANIA & Inga Aalia illustration Karin Sunvisson n March 11, 2010, one of Lithuania’s three na- the Lithuanian political and cultural establishment sought against homosexuality among the population. In 2007 and tional holidays, an annual march of radical to demonstrate that this mixture was compatible, comple- 2008, Vilnius gained notoriety as the only European capital nationalists took place in the heart of Vilnius mentary and even necessary; “Europeanness” was invoked which did not grant permission to park the European Com- with an official permit from the municipality. as a core argument for Lithuania’s prompt inclusion in the mission’s campaign truck “For Diversity — Against Discrimina- Although rather low-key compared with the infamous march European Union. After accession to the EU in 2004, however, tion” in the city center. Kaunas, Lithuania’s second city, made of 2008, when participants chanted openly racist and anti- a more cynical attitude to European integration arose. The la- a similar decision in 2008. Citing safety arguments, the may- Semitic slogans, the march nonetheless retained its unmistak- bels “Lithuanian” and “European” are no longer assumed to ors of Vilnius and Kaunas nonetheless made such statements able ultra-nationalist feel, and slogans such as “Lithuania for be complementary. Many of the country’s leading politicians as, “There will be no advertising for sexual minorities”, and Lithuanians” were hardly more palatable. That did not seem and social personalities are to an increasing extent portraying “Tolerance has its limits”.2 In a separate incident, trolleybuses to faze the protagonists, including a parliamentarian from the the “liberal European agenda” as antithetical and even threat- in Vilnius and Kaunas carrying awareness campaign messages Homeland Union party who had applied for the municipal ening to “traditional Lithuanian values”. -

Fighters-For-Freedom.Pdf

FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM Lithuanian Partisans Versus the U.S.S.R. by Juozas Daumantas This is a factual, first-hand account of the activities of the armed resistance movement in Lithuania during the first three years of Russian occupation (1944-47) and of the desperate conditions which brought it about. The author, a leading figure in the movement, vividly describes how he and countless other young Lithuanian men and women were forced by relentless Soviet persecutions to abandon their everyday activities and take up arms against their nation’s oppressors. Living as virtual outlaws, hiding in forests, knowing that at any moment they might be hunted down and killed like so many wild animals, these young freedom fighters were nonetheless determined to strike back with every resource at their command. We see them risking their lives to protect Lithuanian farmers against Red Army marauders, publishing underground news papers to combat the vast Communist propaganda machine, even pitting their meager forces against the dreaded NKVD and MGB. JUOZAS DAUMANTAS FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM LITHUANIAN PARTISANS VERSUS THE U.S.S.R. (1944-1947) Translated from the Lithuanian by E. J. Harrison and Manyland Books SECOND EDITION FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM Copyright © 1975 by Nijole Brazenas-Paronetto Published by The Lithuanian Canadian Committee for Human Rights, 1988 1011 College Street, Toronto, Ontario, M6H 1A8 Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 74-33547 ISBN 0-87141-049-4 CONTENTS Page Prelude: July, 1944 5 Another “Liberation” 10 The Story of the Red Army Soldier, -

Agenda EN Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenković on Tuesday at 8:30

The Week Ahead 13 – 19 January 2020 Plenary session, Strasbourg Plenary session, Strasbourg Future of Europe. Parliament will set out its vision on the set-up and scope of the 2020- 2022 “Conference on the Future of Europe”, following a debate with Council President Michel and Commission President von der Leyen on Wednesday morning. In an unprecedented bottom-up approach, MEPs want citizens to be at the core of EU reform. ( debate and vote Wednesday) Green Deal/Transition Fund. MEPs will discuss with the Commission legislative Agenda proposals on the “Just Transition Mechanism and Fund”, which seek to help EU communities succeed in making the transition to low carbon in a debate on Tuesday. Parliament will also outline its views on the overall package of the Green Deal in a vote on a resolution on Wednesday. Croatian Presidency. Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenković will present the priorities of the rotating Council presidency for the next six months, focussing on a Europe that is developing, a Europe that connects, a Europe that protects, and an influential Europe. EP President Sassoli and Prime Minister Plenković will hold a press conference at 12.00. ( Tuesday) Brexit/Citizens’ rights. MEPs are set to express their concern over how the UK and EU27 governments will manage citizens’ rights after Brexit. The draft text highlights that the fair and balanced provisions to protect citizens’ rights during and after the transition period, contained in the Withdrawal Agreement, must be thoroughly implemented. ( Wednesday) Iran/Iraq. MEPs will debate the consequences of the latest confrontation between the US and Iran with EU Foreign Policy Chief Josep Borrell. -

2020-Activity-Report.Pdf

— 2020 — WILFRIED MARTENS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN STUDIES ACTIVITY REPORT © February 2021 - Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies 2020’s label will unfortunately be, above all, the year of Table of Contents the COVID-19 pandemic. It has marked the fates of many people, the way of life we used to enjoy, the way in which we communicated and worked, and in fact the entire world. On one hand, it has caused unprecedent fear for Welcome 04 human lives, but on the other hand it stimulated signifi- cant ones, such as the great effort to effectively coordi- nate the fight against the virus and the decision to create the Recovery Fund – Next Generation EU. However, we Publications 07 ended the year with the faith that the vaccines humanity European View 08 developed will save human lives and gradually get the Publications in 2020 10 situation under control, also eliminating the pandemic’s devastating impact on the economy. Another sad moment of 2020 for the EU was, of course, the UK’s official exit. It was a very painful process, but Events 13 largely chaotic on the British side. Even though we Events in 2020 14 parted “in an orderly fashion”, the consequences will be Economic Ideas Forum Brussels 2020 16 felt on both sides for years to come. 10th Transatlantic Think Tank Conference 20 Another unquestionably significant event of 2020 was the US presidential election. The pandemic, along with the events surrounding the US election, such as the Common Projects 23 attack on the Capitol, proved how fragile democracy NET@WORK 24 is, as are we. -

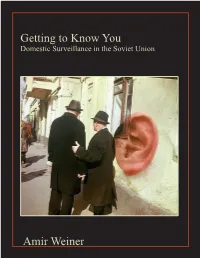

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime