Necrotizing Periodontitis in a Heavy Smoker and Tobacco Chewer – a Case Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: a Case Report

Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report Abstract Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition characterized by varying degrees of gingival hyperplasia. Gingival fibromatosis usually occurs as an isolated disorder or can be associated with a variety of other syndromes. A 33-year-old male patient who had a generalized severe gingival overgrowth covering two thirds of almost all maxillary and mandibular teeth is reported. A mucoperiosteal flap was performed using interdental and crevicular incisions to remove excess gingival tissues and an internal bevel incision to reflect flaps. The patient was treated 15 years ago in the same clinical facility using the same treatment strategy. There was no recurrence one year following the most recent surgery. Keywords: Gingival hyperplasia, hereditary gingival hyperplasia, HGF, hereditary disease, therapy, mucoperiostal flap Citation: S¸engün D, Hatipog˘lu H, Hatipog˘lu MG. Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report. J Contemp Dent Pract 2007 January;(8)1:090-096. © Seer Publishing 1 The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, Volume 8, No. 1, January 1, 2007 Introduction Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF), also Ankara, Turkey with a complaint of recurrent known as elephantiasis gingiva, hereditary generalized gingival overgrowth. The patient gingival hyperplasia, idiopathic fibromatosis, had presented himself for examination at the and hypertrophied gingival, is a rare condition same clinic with the same complaint 15 years (1:750000)1 which can present as an isolated ago. At that time, he was treated with full-mouth disorder or more rarely as a syndrome periodontal surgery after the diagnosis of HGF component.2,3 This condition is characterized by had been made following clinical and histological a slow and progressive enlargement of both the examination (Figures 1 A-B). -

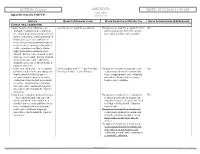

02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix a to Rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01

ACTION: Original AMENDED DATE: 02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix A to rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01 SERVICE QUANTITY/FREQUENCY LIMIT OTHER CONDITION OR RESTRICTION PRIOR AUTHORIZATION (PA) REQUIRED CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION Comprehensive oral evaluation – A 1 per 5 years per provider per patient No payment is made for a comprehensive No thorough evaluation and recording of oral evaluation performed in conjunc- the extraoral and intraoral hard and soft tion with a periodic oral evaluation. tissues, it includes a dental and medical history and a general health assess- ment. It may encompass such matters as dental caries, missing or unerupted teeth, restorations, occlusal relation- ships, periodontal conditions, peri- odontal charting, tissue anomalies, and oral cancer screening. Interpretation of information may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Periodic oral evaluation – An evaluation Patient younger than 21: 1 per 180 days No payment is made for a periodic oral No performed to determine any changes in Patient 21 or older: 1 per 365 days evaluation performed in conjunction dental and medical health since a with a comprehensive oral evaluation previous comprehensive or periodic nor within 180 days after a compre- evaluation, it may include periodontal hensive oral evaluation. screening. Interpretation of informa- tion may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Limited oral evaluation, problem-focused No payment is made if the evaluation is No – An evaluation limited to a specific performed solely for the purpose of oral health problem or complaint, it adjusting dentures, except as specified includes any necessary palliative treat- in Chapter 5160-28 of the Adminis- ment. -

Essential Dental (Pdf)

Dental Essential Plans 2 Plans1 for Individuals & Families with Optional Vision Benefits2 Table of Contents Optional Vision Benefits 5 Why Dental Essential? 2 Exclusions & Limitations 6 Dental Essential & Notice of Privacy Practices 10 Dental Essential Preferred 3 Wisconsin Outline of Coverage 14 Hearing Discounts 4 California Notices 18 Golden Rule Insurance Company is the underwriter of these plans. This product is administered by Dental Benefit Providers, Inc. Policy Forms GRI-DEN3-JR, -01 (AL), -02 (AZ), -03 (AR), -04 (CA), -05 (CO), -06 (CT), (DE), -08 (DC), -09 (FL), -10 (GA), -51 (HI), -12 (IL), -13 (IN), -14 (IA), -15 (KS), -16 (KY), -17 (LA), -19 (MD), -21 (MI), -22 (MN), -23 (MS), -24 (MO), -26 (NE), -28 (NH), -30 (NM), -32 (NC), -33 (ND), -35 (OK), -36 (OR), -37 (PA), -38 (RI), -39 (SC), -40 (SD), -41 (TN), -42 (TX), -43 (UT), -44 (VT), -45 (VA), -47 (WV), and -48 (WI); GRI-DEN3-JR-PB, -11 (ID), -34 (OH), -46 (WA); GRI-DEN3-JR-PBM, -11 (ID), -34 (OH), -46 (WA) 1 Essential Preferred is the only plan available in CO and MN. 2 The optional vision benefit is not available in MN, RI or WA. The ratio of incurred claims to earned premiums (loss-ratio) for total accident and health for Golden Rule Insurance Company in all states in 2019 was 62.4%. This is an outline only and is not intended to serve as a legal interpretation of benefits. Reasonable effort has been made to have this outline represent the intent of contract language. However, the contract language stands alone and the complete terms of the coverage will be determined by the policy. -

Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT

Richa et al.: Management of Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis and its management: A Rare Case of Homozygous Twins Richa1, Neeraj Kumar2, Krishan Gauba3, Debojyoti Chatterjee4 1-Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Hospital, Rohini, Delhi. 2-Senior Resident, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Correspondence to: Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research , Chandigarh, India. 3-Professor and Head, Dr. Richa, Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and Department of Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Research, Chandigarh, India. 4-Senior Resident, Department of Histopathology, Oral Health Sciences Hospital, Rohini, Delhi Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. Contact Us: www.ijohmr.com ABSTRACT Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition which manifests itself by gingival overgrowth covering teeth to variable degree i.e. either isolated or as part of a syndrome. This paper presented two cases of generalized and severe HGF in siblings without any systemic illness. HGF was confirmed based on family history, clinical and histological examination. Management of both the cases was done conservatively. Quadrant wise gingivectomy using ledge and wedge method was adopted and followed for 12 months. The surgical procedure yielded functionally and esthetically satisfying results with no recurrence. KEYWORDS: Gingival enlargement, Hereditary, homozygous, Gingivectomy AA swollen gums. The patient gave a history of swelling of upper gums that started 2 years back which gradually aaaasasasss INTRODUCTION increased in size. The child’s mother denied prenatal Hereditary Gingival Enlargement, being a rare entity, is exposure to tobacco, alcohol, and drug. -

Gingivectomy Approaches: a Review

ISSN: 2469-5734 Peres et al. Int J Oral Dent Health 2019, 5:099 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5734/1510099 Volume 5 | Issue 3 International Journal of Open Access Oral and Dental Health REVIEW ARTICLE Gingivectomy Approaches: A Review Millena Mathias Peres1, Tais da Silva Lima¹, Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho1,2*, Igor Mariotto Beneti1,2, Marcelo Augusto Rudnik Gomes1,2 and Patrícia Garani Fernandes1,2 1University Center North Paulista (Unorp) Dental School, Brazil 2Department of Scientific Production, Post Graduate and Continuing Education (Unipos), Brazil Check for *Corresponding author: Prof. Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho, Department of Scientific Production, Post updates Graduate and Continuing Education (Unipos), Street Ipiranga, 3460, São José do Rio Preto SP, 15020-040, Brazil, Tel: +55-(17)-98166-6537 gingival tissue, and can be corrected with surgical tech- Abstract niques such as gingivectomy. Many patients seek dental offices for a beautiful, harmoni- ous smile to boost their self-esteem. At present, there is a Gingivectomy is a technique that is easy to carry great search for oral aesthetics, where the harmony of the out and is usually well accepted by patients, who, ac- smile is determined not only by the shape, position, and col- cording to the correct indications, can obtain satisfac- or of teeth but also by the gingival tissue. The present study aimed to establish the etiology and diagnosis of the gingi- tory results in dentogingival aesthetics and harmony val smile, with the alternative of correcting it with very safe [3]. surgical techniques such as gingivectomy. The procedure consists in the elimination of gingival deformities resulting The procedure consists in the removal of gingival de- in a better gingival contour. -

The Treatment of Acute Neerotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis Anne C

Penodontics The treatment of acute neerotizing ulcerative gingivitis Anne C. Hartnett* / Jacob Shiloah** The destruction of tbe interdental papillae and formation of permanent gingiva! craierx are common sequelae of acute neerotizing uleerative gingivitis. These craters ean be disfiguring, especially in the anterior gingiva, and ean act as a nidus for recurrent epi- sodes. Traditional therapy has emphasized a stirgieal approach for elimination of Ihese defects, often increasing the esthelie problems. The pwpose of this paper is to review the treatment modalities of acitte neerotizing itlcerative gingivitis and ¡Ilústrate an al- ternative treatment approach of periodic sealing, root planing, and antimicrohiai rinses with 0.12% chlorhexidine. With this therapeutic regimen, the disease proeess ean be reversed and damaged papillae may regenérale. (Quintessence Int 1991:22:95-100.) Introduction chetes, fusifonn bacteria, and species of Bacteroides are the organisms most frequently cultivated from Acute neerotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) is a these lesions,' a definitive periodontal pathogen has rapidly destructive, noncommunicable, gingival infec- yet to be tmplicated in the onset or progression of tion of complex etiology. It is characterized by necrosis ANUG. A susceptible animal model in which to study of the crest of the gingival papillae, spontaneous ANUG has not been found. bleeding, pain, and halitosis. If left untreated, it may Previous studies have speculated on the importance spread laterally and apically to involve the entire -

Literature Review

LITERATURE REVIEW PERIODONTAL ANATOMY The tissues which surround the teeth, and provide the support necessary for normal function form the periodontium (Greek peri- “around”; odont-, “tooth”). The periodontium is comprised of the gingiva, periodontal ligament, alveolar bone, and cementum. The gingiva is anatomically divided into the marginal (unattached), attached and interdental gingiva. The marginal gingiva forms the coronal border of the gingiva which surrounds the tooth, but is not adherent to it. The cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) is where the crown enamel and the root cementum meet. The Marginal gingiva in normal periodontal tissues extends approximately 2mm coronal tothe CEJ. Microscopically the gingiva is comprised of a central core of dense connective tissue and an outer surface of stratified squamous epithelium. The space between the marginal gingiva and the external tooth surface is termed the gingival sulcus. The normal depth of the gingival sulcus, and corresponding width of the marginal gingival, is variable. In general, sulcular depths less than 2mm to 3mm in humans and animals are considered normal1. Ranges from 0.0mm to 6.0mm 2 have been reported.. The depth of a sulcus histologically is not necessarily the same as the depth which could be measured with a periodontal probe. The probing depth of a clinically normal human or canine gingival sulcus is 2 to 3 mm2 1. Attached gingiva is bordered coronally by the apical extent of the unattached gingiva, which is, in turn, defined by the depth of the gingival sulcus. The apical extent of the attached 1 gingiva is the mucogingival junction on the facial aspect of the mandible and maxilla, and the lingual aspect of the mandibular attached gingiva. -

Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports

DOI: 10.21276/sjmcr.2016.4.6.16 Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports ISSN 2347-6559 (Online) Sch J Med Case Rep 2016; 4(6):416-419 ISSN 2347-9507 (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publishers (SAS Publishers) (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report with Review of Literature Jesudass Govada1, Sridhar Reddy Erugula2, Narendra Kumar Narahari3, Vijay Kumar R4,Rajajee KTSS5, Sudhir Kumar Vujhini6 1Associate Professor, Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, Government Dental College and Hospital, RIMS, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh, India 2Senior lecturer, Department of Oral Pathology, MNR Dental College and Hospital, Sangareddy, Telangana, India 3Assistant Professor, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, India. 4Assistant Professor, Dept. of Dentistry, Govt. Dental College, Ananthapur,, Andhra Pradesh, India 5Reader, Dept of Pedodontics, Anil Neerukonda Institute of Dental Sciences, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India. 6Assistant Professor, Transfusion Medicine, Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, India *Corresponding author Sudhir Kumar Vujhini Email: [email protected] Abstract: Gingival fibromatosis is characterized by localized or generalized fibrous enlargement of the gingivae, mainly around permanent teeth. Gingival fibromatosis affects only the masticatory mucosa and does not extend beyond the muco-gingival junction. This article describes an unusual case of hereditary gingival fibromatosis with delayed eruption of permanent teeth in an 11 year-old girl and her younger sibling. The patient presented with severely enlarged gingival tissues affecting both arches and multiple retained deciduous. Most of the permanent teeth were not erupted. She had no associated symptoms to suggest any syndrome but there was family history of similar disorder with father and paternal aunt. -

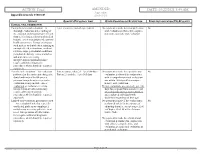

AMENDED ACTION: Final DATE: 03/22/2021 8:49 AM

ACTION: Final AMENDED DATE: 03/22/2021 8:49 AM Appendix Appendix A to rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01 SERVICE QUANTITY/FREQUENCY LIMIT OTHER CONDITION OR RESTRICTION PRIOR AUTHORIZATION (PA) REQUIRED CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION Comprehensive oral evaluation – A 1 per 5 years per provider per patient No payment is made for a comprehensive No thorough evaluation and recording of oral evaluation performed in conjunc- the extraoral and intraoral hard and soft tion with a periodic oral evaluation. tissues, it includes a dental and medical history, cancer evaluation and a general health assessment. It may encompass such matters as dental caries, missing or unerupted teeth, restorations, occlusal relation- ships, periodontal conditions, periodontal charting, tissue anomalies, and oral cancer screening. Interpretation of information may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Periodic oral evaluation – An evaluation Patient younger than 21: 1 per 180 days No payment is made for a periodic oral No performed to determine any changes in Patient 21 or older: 1 per 365 days evaluation performed in conjunction dental and medical health since a with a comprehensive oral evaluation previous comprehensive or periodic nor within 180 days after a compre- evaluation, it may include, cancer hensive oral evaluation. evaluation, periodontal screening. Dental evaluations are covered 1 per 180 Interpretation of information may days for pregnant women and several require additional diagnostic special groups such as foster children procedures, which should be reported and employed individuals with separately. disabilities regardless of their age. Limited oral evaluation, problem-focused No payment is made if the evaluation is No – An evaluation limited to a specific performed solely for the purpose of oral health problem or complaint, it adjusting dentures, except as specified includes any necessary palliative treat- in Chapter 5160-28 of the Adminis- ment. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Gingivectomy and Gingivoplasty

Gingivectomy and Gingivoplasty Hamad Alzoman, BDS, M.S. Diplomate, The American Board of Periodontology Gingivectomy • The excision of a portion of the gingiva; usually performed to reduce the soft tissue wall of a periodontal pocket Glossary of Periodontal Terms 4rth Edition. The American Academy of Periodontology. Gingivoplasty • A surgical reshaping of the gingiva. Glossary of Periodontal Terms 4rth Edition. The American Academy of Periodontology. Gingivectomy Gingivoplasty Indications • Elimination of periodontal pocket 3-5 mm • Elimination of gingival enlargement • Asymmetrical or unaesthetic gingival topography • Suprabony pockets which need access for restorative dentistry Indications • Elimination of periodontal pocket 3-5 mm X X Indications • Elimination of gingival enlargement Localized Generalized Indications Asymmetrical or unaesthetic gingival topography Indications • Suprabony pockets which need access for restorative dentistry Contraindications • Presence of intrabony defect • Pockets extending to or beyond the mucogingival junction or when there is minimal attached gingiva • Esthetic consideration • High caries rate • Severely inflamed tissue Contraindications • Presence of intrabony defect Contraindications • Pockets extending to or beyond the mucogingival junction or when there is minimal attached gingiva Instruments Instruments Instruments Technique Local anesthesia injection Technique Pocket Marking Technique Uninterrupted bevelled incision with Krickland knife Technique Technique Use of Orban papilla knife Technique -

Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: Characteristics and Treatment Approach

J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(4):e599-602. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis Journal section: Periodontology doi:10.4317/jced.53644 Publication Types: Case Report http://dx.doi.org/10.4317/jced.53644 Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: Characteristics and treatment approach Pedro J. Almiñana-Pastor 1, Pedro J. Buitrago-Vera 2, Francisco M. Alpiste-Illueca 3, Montserrat Catalá-Piza- rro 4 1 DD, Post-graduated in Periodontics, Department d´Estomatologia, Facultad de Medicina y Odontologia, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain 2 MD DD, PhD in Medicine. Adjunct Professor of Periodontics, Facultad de Medicina y Odontologia, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain 3 MD DD, PhD in Medicine. Assistant Professor of Periodontics, Department d´Estomatologia, Facultad de Medicina y Odontologia, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain 4 MD DD, PhD in Medicine. Associate Professor of Pediatric Dentistry, Department d´Estomatologia, Facultad de Medicina y Odontologia, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain Correspondence: Stomatology Department University of Valencia C/Gascó Oliag 1, 46010 Valencia, Spain Almiñana-Pastor PJ, Buitrago-Vera PJ, Alpiste-Illueca FM, Catalá-Piza- [email protected] rro M. Hereditary gingival fifibromatosis: bromatosis: Characteristics and treatment ap-ap- proach. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(4):e599-602. http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/volumenes/v9i4/jcedv9i4p599.pdf Received: 04/12/2016 Article Number: 53644 http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/indice.htm Accepted: 07/01/2017 © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - eISSN: 1989-5488 eMail: [email protected] Indexed in: Pubmed Pubmed Central® (PMC) Scopus DOI® System Abstract Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare disorder characterized by a benign, non-hemorrhagic, fibrous gingival overgrowth that can appear in isolation or as part of a syndrome.