HIV and It's Periodontal Sequele: Review © 2021 IJADS Received: 25-11-2020 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LYME DISEASE Other Names: Borrelia Burgdorferi

LYME DISEASE Other names: Borrelia burgdorferi CAUSE Lyme disease is caused by a spirochete bacteria (Borrelia burgdorferi) that is transmitted through the bite from an infected arthropod vector, the black-legged or deer tick Ixodes( scapularis). SIGNIFICANCE Lyme disease can infect people and some species of domestic animals (cats, dogs, horses, and cattle) causing mild to severe illness. Although wildlife can be infected by the bacteria, it typically does not cause illness in them. TRANSMISSION The bacteria has been observed in the blood of a number of wildlife species including several bird species but rarely appears to cause illness in these species. White-footed mice, eastern chipmunks, and shrews serve as the primary natural reservoirs for Lyme disease in eastern and central parts of North America. Other species appear to have low competencies as reservoirs for the bacteria. The transmission of Lyme disease is relatively convoluted due to the complex life cycle of the black-legged tick. This tick has multiple developmental stages and requires three hosts during its life cycle. The life cycle begins with the eggs of the ticks that are laid in the spring and from which larval ticks emerge. Larval ticks do not initially carryBorrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria must be acquired from their hosts they feed upon that are carriers of the bacteria. Through the summer the larval ticks feed on the blood of their first host, typically small mammals and birds. It is at this point where ticks may first acquireBorrelia burgdorferi. In the fall the larval ticks develop into nymphs and hibernate through the winter. -

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Phagocytosis of Borrelia Burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytes Adriana R

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn UCHC Articles - Research University of Connecticut Health Center Research 1-2008 Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytes Adriana R. Cruz University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Meagan W. Moore University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Carson J. La Vake University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Christian H. Eggers University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Juan C. Salazar University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/uchcres_articles Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cruz, Adriana R.; Moore, Meagan W.; La Vake, Carson J.; Eggers, Christian H.; Salazar, Juan C.; and Radolf, Justin D., "Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytes" (2008). UCHC Articles - Research. 182. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/uchcres_articles/182 Authors Adriana R. Cruz, Meagan W. Moore, Carson J. La Vake, Christian H. Eggers, Juan C. Salazar, and Justin D. Radolf This article is available at OpenCommons@UConn: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/uchcres_articles/182 INFECTION AND IMMUNITY, Jan. 2008, p. 56–70 Vol. 76, No. 1 0019-9567/08/$08.00ϩ0 doi:10.1128/IAI.01039-07 Copyright © 2008, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytesᰔ Adriana R. Cruz,1†‡ Meagan W. Moore,1† Carson J. -

Long-Term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: a Case Report

Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report Abstract Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition characterized by varying degrees of gingival hyperplasia. Gingival fibromatosis usually occurs as an isolated disorder or can be associated with a variety of other syndromes. A 33-year-old male patient who had a generalized severe gingival overgrowth covering two thirds of almost all maxillary and mandibular teeth is reported. A mucoperiosteal flap was performed using interdental and crevicular incisions to remove excess gingival tissues and an internal bevel incision to reflect flaps. The patient was treated 15 years ago in the same clinical facility using the same treatment strategy. There was no recurrence one year following the most recent surgery. Keywords: Gingival hyperplasia, hereditary gingival hyperplasia, HGF, hereditary disease, therapy, mucoperiostal flap Citation: S¸engün D, Hatipog˘lu H, Hatipog˘lu MG. Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report. J Contemp Dent Pract 2007 January;(8)1:090-096. © Seer Publishing 1 The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, Volume 8, No. 1, January 1, 2007 Introduction Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF), also Ankara, Turkey with a complaint of recurrent known as elephantiasis gingiva, hereditary generalized gingival overgrowth. The patient gingival hyperplasia, idiopathic fibromatosis, had presented himself for examination at the and hypertrophied gingival, is a rare condition same clinic with the same complaint 15 years (1:750000)1 which can present as an isolated ago. At that time, he was treated with full-mouth disorder or more rarely as a syndrome periodontal surgery after the diagnosis of HGF component.2,3 This condition is characterized by had been made following clinical and histological a slow and progressive enlargement of both the examination (Figures 1 A-B). -

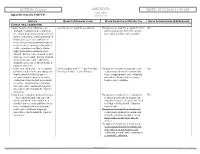

02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix a to Rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01

ACTION: Original AMENDED DATE: 02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix A to rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01 SERVICE QUANTITY/FREQUENCY LIMIT OTHER CONDITION OR RESTRICTION PRIOR AUTHORIZATION (PA) REQUIRED CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION Comprehensive oral evaluation – A 1 per 5 years per provider per patient No payment is made for a comprehensive No thorough evaluation and recording of oral evaluation performed in conjunc- the extraoral and intraoral hard and soft tion with a periodic oral evaluation. tissues, it includes a dental and medical history and a general health assess- ment. It may encompass such matters as dental caries, missing or unerupted teeth, restorations, occlusal relation- ships, periodontal conditions, peri- odontal charting, tissue anomalies, and oral cancer screening. Interpretation of information may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Periodic oral evaluation – An evaluation Patient younger than 21: 1 per 180 days No payment is made for a periodic oral No performed to determine any changes in Patient 21 or older: 1 per 365 days evaluation performed in conjunction dental and medical health since a with a comprehensive oral evaluation previous comprehensive or periodic nor within 180 days after a compre- evaluation, it may include periodontal hensive oral evaluation. screening. Interpretation of informa- tion may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Limited oral evaluation, problem-focused No payment is made if the evaluation is No – An evaluation limited to a specific performed solely for the purpose of oral health problem or complaint, it adjusting dentures, except as specified includes any necessary palliative treat- in Chapter 5160-28 of the Adminis- ment. -

Essential Dental (Pdf)

Dental Essential Plans 2 Plans1 for Individuals & Families with Optional Vision Benefits2 Table of Contents Optional Vision Benefits 5 Why Dental Essential? 2 Exclusions & Limitations 6 Dental Essential & Notice of Privacy Practices 10 Dental Essential Preferred 3 Wisconsin Outline of Coverage 14 Hearing Discounts 4 California Notices 18 Golden Rule Insurance Company is the underwriter of these plans. This product is administered by Dental Benefit Providers, Inc. Policy Forms GRI-DEN3-JR, -01 (AL), -02 (AZ), -03 (AR), -04 (CA), -05 (CO), -06 (CT), (DE), -08 (DC), -09 (FL), -10 (GA), -51 (HI), -12 (IL), -13 (IN), -14 (IA), -15 (KS), -16 (KY), -17 (LA), -19 (MD), -21 (MI), -22 (MN), -23 (MS), -24 (MO), -26 (NE), -28 (NH), -30 (NM), -32 (NC), -33 (ND), -35 (OK), -36 (OR), -37 (PA), -38 (RI), -39 (SC), -40 (SD), -41 (TN), -42 (TX), -43 (UT), -44 (VT), -45 (VA), -47 (WV), and -48 (WI); GRI-DEN3-JR-PB, -11 (ID), -34 (OH), -46 (WA); GRI-DEN3-JR-PBM, -11 (ID), -34 (OH), -46 (WA) 1 Essential Preferred is the only plan available in CO and MN. 2 The optional vision benefit is not available in MN, RI or WA. The ratio of incurred claims to earned premiums (loss-ratio) for total accident and health for Golden Rule Insurance Company in all states in 2019 was 62.4%. This is an outline only and is not intended to serve as a legal interpretation of benefits. Reasonable effort has been made to have this outline represent the intent of contract language. However, the contract language stands alone and the complete terms of the coverage will be determined by the policy. -

Canine Lyme Borrelia

Canine Lyme Borrelia Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria are the cause of Lyme disease in humans and animals. They can be visualized by darkfild microscopy as "corkscrew-shaped" motile spirochetes (400 x). Inset: The black-legged tick, lxodes scapularis (deer tick), may carry and transmit Borrelia burgdorferi to humans and animals during feeding, and thus transmit Lyme disease. Samples: Blood EDTA-blood as is, purple-top tubes or EDTA-blood preserved in sample buffer (preferred) Body fluids Preserved in sample buffer Notes: Send all samples at room temperature, preferably preserved in sample buffer MD Submission Form Interpretation of PCR Results: High Positive Borrelia spp. infection (interpretation must be correlated to (> 500 copies/ml swab) clinical symptoms) Low Positive (<500 copies/ml swab) Negative Borrelia spp. not detected Lyme Borreliosis Lyme disease is caused by spirochete bacteria of a subgroup of Borrelia species, called Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Only one species, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, is known to be present in the USA, while at least four pathogenic species, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. japonica have been isolated in Europe and Asia (Aguero- Rosenfeld et al., 2005). B. burgdorferi sensu lato organisms are corkscrew-shaped, motile, microaerophilic bacteria of the order Spirochaetales. Hard-shelled ticks of the genus Ixodes transmit B. burgdorferi by attaching and feeding on various mammalian, avian, and reptilian hosts. In the northeastern states of the US Ixodes scapularis, the black-legged deer tick, is the predominant vector, while at the west coast Lyme borreliosis is maintained by a transmission cycle which involves two tick species, I. -

Borrelia Burgdorferi and Treponema Pallidum: a Comparison of Functional Genomics, Environmental Adaptations, and Pathogenic Mechanisms

PERSPECTIVE SERIES Bacterial polymorphisms Martin J. Blaser and James M. Musser, Series Editors Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum: a comparison of functional genomics, environmental adaptations, and pathogenic mechanisms Stephen F. Porcella and Tom G. Schwan Laboratory of Human Bacterial Pathogenesis, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, Hamilton, Montana, USA Address correspondence to: Tom G. Schwan, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 903 South 4th Street, Hamilton, Montana 59840, USA. Phone: (406) 363-9250; Fax: (406) 363-9445; E-mail: [email protected]. Spirochetes are a diverse group of bacteria found in (6–8). Here, we compare the biology and genomes of soil, deep in marine sediments, commensal in the gut these two spirochetal pathogens with reference to their of termites and other arthropods, or obligate parasites different host associations and modes of transmission. of vertebrates. Two pathogenic spirochetes that are the focus of this perspective are Borrelia burgdorferi sensu Genomic structure lato, a causative agent of Lyme disease, and Treponema A striking difference between B. burgdorferi and T. pal- pallidum subspecies pallidum, the agent of venereal lidum is their total genomic structure. Although both syphilis. Although these organisms are bound togeth- pathogens have small genomes, compared with many er by ancient ancestry and similar morphology (Figure well known bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Mycobac- 1), as well as by the protean nature of the infections terium tuberculosis, the genomic structure of B. burgdorferi they cause, many differences exist in their life cycles, environmental adaptations, and impact on human health and behavior. The specific mechanisms con- tributing to multisystem disease and persistent, long- term infections caused by both organisms in spite of significant immune responses are not yet understood. -

Investigation of the Lipoproteome of the Lyme Disease Bacterium

INVESTIGATION OF THE LIPOPROTEOME OF THE LYME DISEASE BACTERIUM BORRELIA BURGDORFERI BY Alexander S. Dowdell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Microbiology, Molecular Genetics & Immunology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________ Wolfram R. Zückert, Ph.D., Chairperson _____________________________ Indranil Biswas, Ph.D. _____________________________ Mark Fisher, Ph.D. _____________________________ Joe Lutkenhaus, Ph.D. _____________________________ Michael Parmely, Ph.D. Date Defended: April 27th, 2017 The dissertation committee for Alexander S. Dowdell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: INVESTIGATION OF THE LIPOPROTEOME OF THE LYME DISEASE BACTERIUM BORRELIA BURGDORFERI _____________________________ Wolfram R. Zückert, Ph.D., Chairperson Date Approved: May 4th, 2017 ii Abstract The spirochete bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi is the causative agent of Lyme borreliosis, the top vector-borne disease in the United States. B. burgdorferi is transmitted by hard- bodied Ixodes ticks in an enzootic tick/vertebrate cycle, with human infection occurring in an accidental, “dead-end” fashion. Despite the estimated 300,000 cases that occur each year, no FDA-approved vaccine is available for the prevention of Lyme borreliosis in humans. Development of new prophylaxes is constrained by the limited understanding of the pathobiology of B. burgdorferi, as past investigations have focused intensely on just a handful of identified proteins that play key roles in the tick/vertebrate infection cycle. As such, identification of novel B. burgdorferi virulence factors is needed in order to expedite the discovery of new anti-Lyme therapeutics. The multitude of lipoproteins expressed by the spirochete fall into one such category of virulence factor that merits further study. -

Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT

Richa et al.: Management of Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis and its management: A Rare Case of Homozygous Twins Richa1, Neeraj Kumar2, Krishan Gauba3, Debojyoti Chatterjee4 1-Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Hospital, Rohini, Delhi. 2-Senior Resident, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Correspondence to: Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research , Chandigarh, India. 3-Professor and Head, Dr. Richa, Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and Department of Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Research, Chandigarh, India. 4-Senior Resident, Department of Histopathology, Oral Health Sciences Hospital, Rohini, Delhi Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. Contact Us: www.ijohmr.com ABSTRACT Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition which manifests itself by gingival overgrowth covering teeth to variable degree i.e. either isolated or as part of a syndrome. This paper presented two cases of generalized and severe HGF in siblings without any systemic illness. HGF was confirmed based on family history, clinical and histological examination. Management of both the cases was done conservatively. Quadrant wise gingivectomy using ledge and wedge method was adopted and followed for 12 months. The surgical procedure yielded functionally and esthetically satisfying results with no recurrence. KEYWORDS: Gingival enlargement, Hereditary, homozygous, Gingivectomy AA swollen gums. The patient gave a history of swelling of upper gums that started 2 years back which gradually aaaasasasss INTRODUCTION increased in size. The child’s mother denied prenatal Hereditary Gingival Enlargement, being a rare entity, is exposure to tobacco, alcohol, and drug. -

Gingivectomy Approaches: a Review

ISSN: 2469-5734 Peres et al. Int J Oral Dent Health 2019, 5:099 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5734/1510099 Volume 5 | Issue 3 International Journal of Open Access Oral and Dental Health REVIEW ARTICLE Gingivectomy Approaches: A Review Millena Mathias Peres1, Tais da Silva Lima¹, Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho1,2*, Igor Mariotto Beneti1,2, Marcelo Augusto Rudnik Gomes1,2 and Patrícia Garani Fernandes1,2 1University Center North Paulista (Unorp) Dental School, Brazil 2Department of Scientific Production, Post Graduate and Continuing Education (Unipos), Brazil Check for *Corresponding author: Prof. Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho, Department of Scientific Production, Post updates Graduate and Continuing Education (Unipos), Street Ipiranga, 3460, São José do Rio Preto SP, 15020-040, Brazil, Tel: +55-(17)-98166-6537 gingival tissue, and can be corrected with surgical tech- Abstract niques such as gingivectomy. Many patients seek dental offices for a beautiful, harmoni- ous smile to boost their self-esteem. At present, there is a Gingivectomy is a technique that is easy to carry great search for oral aesthetics, where the harmony of the out and is usually well accepted by patients, who, ac- smile is determined not only by the shape, position, and col- cording to the correct indications, can obtain satisfac- or of teeth but also by the gingival tissue. The present study aimed to establish the etiology and diagnosis of the gingi- tory results in dentogingival aesthetics and harmony val smile, with the alternative of correcting it with very safe [3]. surgical techniques such as gingivectomy. The procedure consists in the elimination of gingival deformities resulting The procedure consists in the removal of gingival de- in a better gingival contour. -

Assessing Lyme Disease Relevant Antibiotics Through Gut Bacteroides Panels

Assessing Lyme Disease Relevant Antibiotics through Gut Bacteroides Panels by Sohum Sheth Abstract: Lyme borreliosis is the most prevalent vector-borne disease in the United States caused by the transmission of bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi harbored by the Ixodus scapularis ticks (Sharma, Brown, Matluck, Hu, & Lewis, 2015). Antibiotics currently used to treat Lyme disease include oral doxycycline, amoxicillin, and ce!riaxone. Although the current treatment is e"ective in most cases, there is need for the development of new antibiotics against Lyme disease, as the treatment does not work in 10-20% of the population for unknown reasons (X. Wu et al., 2018). Use of antibiotics in the treatment of various diseases such as Lyme disease is essential; however, the downside is the development of resistance and possibly deleterious e"ects on the human gut microbiota composition. Like other organs in the body, gut microbiota play an essential role in the health and disease state of the body (Ianiro, Tilg, & Gasbarrini, 2016). Of importance in the microbiome is the genus Bacteroides, which accounts for roughly one-third of gut microbiome composition (H. M. Wexler, 2007). $e purpose of this study is to investigate how antibiotics currently used for the treatment of Lyme disease in%uences the Bacteroides cultures in vitro and compare it with a new antibiotic (antibiotic X) identi&ed in the laboratory to be e"ective against B. burgdorferi. Using microdilution broth assay, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was tested against nine di"erent strains of Bacteroides. Results showed that antibiotic X has a higher MIC against Bacteroides when compared to amoxicillin, ce!riaxone, and doxycycline, making it a promising new drug for further investigation and in vivo studies.