Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: a Case Report

Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report Abstract Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition characterized by varying degrees of gingival hyperplasia. Gingival fibromatosis usually occurs as an isolated disorder or can be associated with a variety of other syndromes. A 33-year-old male patient who had a generalized severe gingival overgrowth covering two thirds of almost all maxillary and mandibular teeth is reported. A mucoperiosteal flap was performed using interdental and crevicular incisions to remove excess gingival tissues and an internal bevel incision to reflect flaps. The patient was treated 15 years ago in the same clinical facility using the same treatment strategy. There was no recurrence one year following the most recent surgery. Keywords: Gingival hyperplasia, hereditary gingival hyperplasia, HGF, hereditary disease, therapy, mucoperiostal flap Citation: S¸engün D, Hatipog˘lu H, Hatipog˘lu MG. Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report. J Contemp Dent Pract 2007 January;(8)1:090-096. © Seer Publishing 1 The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, Volume 8, No. 1, January 1, 2007 Introduction Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF), also Ankara, Turkey with a complaint of recurrent known as elephantiasis gingiva, hereditary generalized gingival overgrowth. The patient gingival hyperplasia, idiopathic fibromatosis, had presented himself for examination at the and hypertrophied gingival, is a rare condition same clinic with the same complaint 15 years (1:750000)1 which can present as an isolated ago. At that time, he was treated with full-mouth disorder or more rarely as a syndrome periodontal surgery after the diagnosis of HGF component.2,3 This condition is characterized by had been made following clinical and histological a slow and progressive enlargement of both the examination (Figures 1 A-B). -

02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix a to Rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01

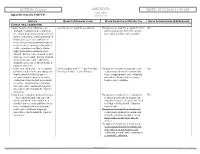

ACTION: Original AMENDED DATE: 02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix A to rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01 SERVICE QUANTITY/FREQUENCY LIMIT OTHER CONDITION OR RESTRICTION PRIOR AUTHORIZATION (PA) REQUIRED CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION Comprehensive oral evaluation – A 1 per 5 years per provider per patient No payment is made for a comprehensive No thorough evaluation and recording of oral evaluation performed in conjunc- the extraoral and intraoral hard and soft tion with a periodic oral evaluation. tissues, it includes a dental and medical history and a general health assess- ment. It may encompass such matters as dental caries, missing or unerupted teeth, restorations, occlusal relation- ships, periodontal conditions, peri- odontal charting, tissue anomalies, and oral cancer screening. Interpretation of information may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Periodic oral evaluation – An evaluation Patient younger than 21: 1 per 180 days No payment is made for a periodic oral No performed to determine any changes in Patient 21 or older: 1 per 365 days evaluation performed in conjunction dental and medical health since a with a comprehensive oral evaluation previous comprehensive or periodic nor within 180 days after a compre- evaluation, it may include periodontal hensive oral evaluation. screening. Interpretation of informa- tion may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Limited oral evaluation, problem-focused No payment is made if the evaluation is No – An evaluation limited to a specific performed solely for the purpose of oral health problem or complaint, it adjusting dentures, except as specified includes any necessary palliative treat- in Chapter 5160-28 of the Adminis- ment. -

Essential Dental (Pdf)

Dental Essential Plans 2 Plans1 for Individuals & Families with Optional Vision Benefits2 Table of Contents Optional Vision Benefits 5 Why Dental Essential? 2 Exclusions & Limitations 6 Dental Essential & Notice of Privacy Practices 10 Dental Essential Preferred 3 Wisconsin Outline of Coverage 14 Hearing Discounts 4 California Notices 18 Golden Rule Insurance Company is the underwriter of these plans. This product is administered by Dental Benefit Providers, Inc. Policy Forms GRI-DEN3-JR, -01 (AL), -02 (AZ), -03 (AR), -04 (CA), -05 (CO), -06 (CT), (DE), -08 (DC), -09 (FL), -10 (GA), -51 (HI), -12 (IL), -13 (IN), -14 (IA), -15 (KS), -16 (KY), -17 (LA), -19 (MD), -21 (MI), -22 (MN), -23 (MS), -24 (MO), -26 (NE), -28 (NH), -30 (NM), -32 (NC), -33 (ND), -35 (OK), -36 (OR), -37 (PA), -38 (RI), -39 (SC), -40 (SD), -41 (TN), -42 (TX), -43 (UT), -44 (VT), -45 (VA), -47 (WV), and -48 (WI); GRI-DEN3-JR-PB, -11 (ID), -34 (OH), -46 (WA); GRI-DEN3-JR-PBM, -11 (ID), -34 (OH), -46 (WA) 1 Essential Preferred is the only plan available in CO and MN. 2 The optional vision benefit is not available in MN, RI or WA. The ratio of incurred claims to earned premiums (loss-ratio) for total accident and health for Golden Rule Insurance Company in all states in 2019 was 62.4%. This is an outline only and is not intended to serve as a legal interpretation of benefits. Reasonable effort has been made to have this outline represent the intent of contract language. However, the contract language stands alone and the complete terms of the coverage will be determined by the policy. -

Gingival Recession – Etiology and Treatment

Preventive_V2N2_AUG11:Preventive 8/17/2011 12:54 PM Page 6 Gingival Recession – Etiology and Treatment Mark Nicolucci, D.D.S., M.S., cert. perio implant, F.R.C.D.(C) Murray Arlin, D.D.S., dip perio, F.R.C.D.(C) his article focuses on the recognition and reason is often a prophylactic one; that is we understanding of recession defects of the want to prevent the recession from getting T oral mucosa. Specifically, which cases are worse. This reasoning is also true for the esthetic treatable, how we treat these cases and why we and sensitivity scenarios as well. Severe chose certain treatments. Good evidence has recession is not only more difficult to treat, but suggested that the amount of height of keratinized can also be associated with food impaction, or attached gingiva is independent of the poor esthetics, gingival irritation, root sensitivity, progression of recession (Miyasato et al. 1977, difficult hygiene, increased root caries, loss of Dorfman et al. 1980, 1982, Kennedy et al. 1985, supporting bone and even tooth loss . To avoid Freedman et al. 1999, Wennstrom and Lindhe these complications we would want to treat even 1983). Such a discussion is an important the asymptomatic instances of recession if we consideration with recession defects but this article anticipate them to progress. However, non- will focus simply on a loss of marginal gingiva. progressing recession with no signs or Recession is not simply a loss of gingival symptoms does not need treatment. In order to tissue; it is a loss of clinical attachment and by know which cases need treatment, we need to necessity the supporting bone of the tooth that distinguish between non-progressing and was underneath the gingiva. -

Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT

Richa et al.: Management of Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis and its management: A Rare Case of Homozygous Twins Richa1, Neeraj Kumar2, Krishan Gauba3, Debojyoti Chatterjee4 1-Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Hospital, Rohini, Delhi. 2-Senior Resident, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Correspondence to: Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research , Chandigarh, India. 3-Professor and Head, Dr. Richa, Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and Department of Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Research, Chandigarh, India. 4-Senior Resident, Department of Histopathology, Oral Health Sciences Hospital, Rohini, Delhi Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. Contact Us: www.ijohmr.com ABSTRACT Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition which manifests itself by gingival overgrowth covering teeth to variable degree i.e. either isolated or as part of a syndrome. This paper presented two cases of generalized and severe HGF in siblings without any systemic illness. HGF was confirmed based on family history, clinical and histological examination. Management of both the cases was done conservatively. Quadrant wise gingivectomy using ledge and wedge method was adopted and followed for 12 months. The surgical procedure yielded functionally and esthetically satisfying results with no recurrence. KEYWORDS: Gingival enlargement, Hereditary, homozygous, Gingivectomy AA swollen gums. The patient gave a history of swelling of upper gums that started 2 years back which gradually aaaasasasss INTRODUCTION increased in size. The child’s mother denied prenatal Hereditary Gingival Enlargement, being a rare entity, is exposure to tobacco, alcohol, and drug. -

Gingivectomy Approaches: a Review

ISSN: 2469-5734 Peres et al. Int J Oral Dent Health 2019, 5:099 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5734/1510099 Volume 5 | Issue 3 International Journal of Open Access Oral and Dental Health REVIEW ARTICLE Gingivectomy Approaches: A Review Millena Mathias Peres1, Tais da Silva Lima¹, Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho1,2*, Igor Mariotto Beneti1,2, Marcelo Augusto Rudnik Gomes1,2 and Patrícia Garani Fernandes1,2 1University Center North Paulista (Unorp) Dental School, Brazil 2Department of Scientific Production, Post Graduate and Continuing Education (Unipos), Brazil Check for *Corresponding author: Prof. Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho, Department of Scientific Production, Post updates Graduate and Continuing Education (Unipos), Street Ipiranga, 3460, São José do Rio Preto SP, 15020-040, Brazil, Tel: +55-(17)-98166-6537 gingival tissue, and can be corrected with surgical tech- Abstract niques such as gingivectomy. Many patients seek dental offices for a beautiful, harmoni- ous smile to boost their self-esteem. At present, there is a Gingivectomy is a technique that is easy to carry great search for oral aesthetics, where the harmony of the out and is usually well accepted by patients, who, ac- smile is determined not only by the shape, position, and col- cording to the correct indications, can obtain satisfac- or of teeth but also by the gingival tissue. The present study aimed to establish the etiology and diagnosis of the gingi- tory results in dentogingival aesthetics and harmony val smile, with the alternative of correcting it with very safe [3]. surgical techniques such as gingivectomy. The procedure consists in the elimination of gingival deformities resulting The procedure consists in the removal of gingival de- in a better gingival contour. -

Diagnosis Questions and Answers

1.0 DIAGNOSIS – 6 QUESTIONS 1. Where is the narrowest band of attached gingiva found? 1. Lingual surfaces of maxillary incisors and facial surfaces of maxillary first molars 2. Facial surfaces of mandibular second premolars and lingual of canines 3. Facial surfaces of mandibular canines and first premolars and lingual of mandibular incisors* 4. None of the above 2. All these types of tissue have keratinized epithelium EXCEPT 1. Hard palate 2. Gingival col* 3. Attached gingiva 4. Free gingiva 16. Which group of principal fibers of the periodontal ligament run perpendicular from the alveolar bone to the cementum and resist lateral forces? 1. Alveolar crest 2. Horizontal crest* 3. Oblique 4. Apical 5. Interradicular 33. The width of attached gingiva varies considerably with the greatest amount being present in the maxillary incisor region; the least amount is in the mandibular premolar region. 1. Both statements are TRUE* 39. The alveolar process forms and supports the sockets of the teeth and consists of two parts, the alveolar bone proper and the supporting alveolar bone; ostectomy is defined as removal of the alveolar bone proper. 1. Both statements are TRUE* 40. Which structure is the inner layer of cells of the junctional epithelium and attaches the gingiva to the tooth? 1. Mucogingival junction 2. Free gingival groove 3. Epithelial attachment * 4. Tonofilaments 1 49. All of the following are part of the marginal (free) gingiva EXCEPT: 1. Gingival margin 2. Free gingival groove 3. Mucogingival junction* 4. Interproximal gingiva 53. The collar-like band of stratified squamous epithelium 10-20 cells thick coronally and 2-3 cells thick apically, and .25 to 1.35 mm long is the: 1. -

The Treatment of Acute Neerotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis Anne C

Penodontics The treatment of acute neerotizing ulcerative gingivitis Anne C. Hartnett* / Jacob Shiloah** The destruction of tbe interdental papillae and formation of permanent gingiva! craierx are common sequelae of acute neerotizing uleerative gingivitis. These craters ean be disfiguring, especially in the anterior gingiva, and ean act as a nidus for recurrent epi- sodes. Traditional therapy has emphasized a stirgieal approach for elimination of Ihese defects, often increasing the esthelie problems. The pwpose of this paper is to review the treatment modalities of acitte neerotizing itlcerative gingivitis and ¡Ilústrate an al- ternative treatment approach of periodic sealing, root planing, and antimicrohiai rinses with 0.12% chlorhexidine. With this therapeutic regimen, the disease proeess ean be reversed and damaged papillae may regenérale. (Quintessence Int 1991:22:95-100.) Introduction chetes, fusifonn bacteria, and species of Bacteroides are the organisms most frequently cultivated from Acute neerotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) is a these lesions,' a definitive periodontal pathogen has rapidly destructive, noncommunicable, gingival infec- yet to be tmplicated in the onset or progression of tion of complex etiology. It is characterized by necrosis ANUG. A susceptible animal model in which to study of the crest of the gingival papillae, spontaneous ANUG has not been found. bleeding, pain, and halitosis. If left untreated, it may Previous studies have speculated on the importance spread laterally and apically to involve the entire -

The-Anatomy-Of-The-Gum-1.Pdf

OpenStax-CNX module: m66361 1 The Anatomy of the Gum* Marcos Gridi-Papp This work is produced by OpenStax-CNX and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 Abstract The gingiva is the part of the masticatory mucosa that surrounds the teeth and extends to the alveolar mucosa. It is rmly attached to the jaw bone and it has keratinized stratied squamous epithelium. The free gingiva is separated from the tooth by the gingival groove and it it very narrow. Most of the gum is the attached gingiva. The interdental gingiva occupies the cervical embrasures in healthy gums but periodontal disease may cause it to receede. Gingival bers attach the gums to the neck of the tooth. They also provide structure to the gingiva and connect the free to the attached gingivae. Figure 1: Maxillary gingiva of a dog. More details1. This chapter is about the gums, which are also called gingivae (singular gingiva). The text will describe the structure of the gingiva and explain its role in periodontal diseases, from gingivitis to abscesses in humans and other mammals. *Version 1.1: Mar 3, 2018 8:43 pm -0600 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 1https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3b/Bull_Terrier_Chico_05.jpg http://cnx.org/content/m66361/1.1/ OpenStax-CNX module: m66361 2 1 Structure The gingiva is part of the masticatory mucosa2 of the mouth. This mucosa is formed by keratinized stratied squamous epithelium and it covers the dorsum of the tongue and hard palate in addition to forming the gingivae. Figure 2: The gingiva surrounds the teeth and contacts the alveolar mucosa. -

The Art and Science of Shade Matching in Esthetic Implant Dentistry, 275 Chapter 12 Treatment Complications in the Esthetic Zone, 301

FUNDAMENTALS OF ESTHETIC IMPLANT DENTISTRY Abd El Salam El Askary FUNDAMENTALS OF ESTHETIC IMPLANT DENTISTRY FUNDAMENTALS OF ESTHETIC IMPLANT DENTISTRY Abd El Salam El Askary Dr. Abd El Salam El Askary maintains a private practice special- Set in 9.5/12.5 pt Palatino izing in esthetic dentistry in his native Egypt. An experienced cli- by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong nician and researcher, he is also very active on the international Printed and bound by C.O.S. Printers Pte. Ltd. conference circuit and as a lecturer on continuing professional development courses. He also holds the position of Associate For further information on Clinical Professor at the University of Florida, Jacksonville. Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: www.blackwellpublishing.com © 2007 by Blackwell Munksgaard, a Blackwell Publishing Company Disclaimer The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific Editorial Offices: research, understanding, and discussion only and are not intended Blackwell Publishing Professional, and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting a 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USA specific method, diagnosis, or treatment by practitioners for any Tel: +1 515 292 0140 particular patient. The publisher and the editor make no represen- 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ tations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness Tel: 01865 776868 of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, including without limitation any implied -

Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports

DOI: 10.21276/sjmcr.2016.4.6.16 Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports ISSN 2347-6559 (Online) Sch J Med Case Rep 2016; 4(6):416-419 ISSN 2347-9507 (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publishers (SAS Publishers) (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report with Review of Literature Jesudass Govada1, Sridhar Reddy Erugula2, Narendra Kumar Narahari3, Vijay Kumar R4,Rajajee KTSS5, Sudhir Kumar Vujhini6 1Associate Professor, Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, Government Dental College and Hospital, RIMS, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh, India 2Senior lecturer, Department of Oral Pathology, MNR Dental College and Hospital, Sangareddy, Telangana, India 3Assistant Professor, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, India. 4Assistant Professor, Dept. of Dentistry, Govt. Dental College, Ananthapur,, Andhra Pradesh, India 5Reader, Dept of Pedodontics, Anil Neerukonda Institute of Dental Sciences, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India. 6Assistant Professor, Transfusion Medicine, Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, India *Corresponding author Sudhir Kumar Vujhini Email: [email protected] Abstract: Gingival fibromatosis is characterized by localized or generalized fibrous enlargement of the gingivae, mainly around permanent teeth. Gingival fibromatosis affects only the masticatory mucosa and does not extend beyond the muco-gingival junction. This article describes an unusual case of hereditary gingival fibromatosis with delayed eruption of permanent teeth in an 11 year-old girl and her younger sibling. The patient presented with severely enlarged gingival tissues affecting both arches and multiple retained deciduous. Most of the permanent teeth were not erupted. She had no associated symptoms to suggest any syndrome but there was family history of similar disorder with father and paternal aunt. -

AMENDED ACTION: Final DATE: 03/22/2021 8:49 AM

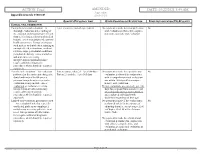

ACTION: Final AMENDED DATE: 03/22/2021 8:49 AM Appendix Appendix A to rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01 SERVICE QUANTITY/FREQUENCY LIMIT OTHER CONDITION OR RESTRICTION PRIOR AUTHORIZATION (PA) REQUIRED CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION Comprehensive oral evaluation – A 1 per 5 years per provider per patient No payment is made for a comprehensive No thorough evaluation and recording of oral evaluation performed in conjunc- the extraoral and intraoral hard and soft tion with a periodic oral evaluation. tissues, it includes a dental and medical history, cancer evaluation and a general health assessment. It may encompass such matters as dental caries, missing or unerupted teeth, restorations, occlusal relation- ships, periodontal conditions, periodontal charting, tissue anomalies, and oral cancer screening. Interpretation of information may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Periodic oral evaluation – An evaluation Patient younger than 21: 1 per 180 days No payment is made for a periodic oral No performed to determine any changes in Patient 21 or older: 1 per 365 days evaluation performed in conjunction dental and medical health since a with a comprehensive oral evaluation previous comprehensive or periodic nor within 180 days after a compre- evaluation, it may include, cancer hensive oral evaluation. evaluation, periodontal screening. Dental evaluations are covered 1 per 180 Interpretation of information may days for pregnant women and several require additional diagnostic special groups such as foster children procedures, which should be reported and employed individuals with separately. disabilities regardless of their age. Limited oral evaluation, problem-focused No payment is made if the evaluation is No – An evaluation limited to a specific performed solely for the purpose of oral health problem or complaint, it adjusting dentures, except as specified includes any necessary palliative treat- in Chapter 5160-28 of the Adminis- ment.