CHAPTER 2. PERIODONTAL DISEASES Section 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Survival of Teeth with Grade Ii Mobility After Periodontal Therapy - a Retrospective Cohort Study

COMPETITIVE STRATEGY MODEL AND ITS IMPACT ON MICRO BUSINESS UNITOF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT BANKSIN JAWA PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) SURVIVAL OF TEETH WITH GRADE II MOBILITY AFTER PERIODONTAL THERAPY - A RETROSPECTIVE COHORT STUDY Keerthana Balaji1, Murugan Thamaraiselvan2,Pradeep D3 1Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals,Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences,Saveetha University,Chennai, India 2Associate ProfessorDepartment of Periodontics,Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences,Saveetha University,162, PH Road,Chennai-600077,TamilNadu, India 3Associate Professor Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery,Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals,Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences,Saveetha University, Chennai, India [email protected],[email protected],[email protected] Keerthana Balaji, Murugan Thamaraiselvan, Pradeep D. SURVIVAL OF TEETH WITH GRADE II MOBILITY AFTER PERIODONTAL THERAPY - A RETROSPECTIVE COHORT STUDY-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7), 530-538. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Tooth mobility, Periodontal therapy , Survival rate, Periodontal diseases. ABSTRACT Assessment of tooth mobility is considered as an integral part of periodontal evaluation because it is one of the important factors that determine the prognosis of periodontal diseases.The main purpose of the study was to evaluate the survival rate of teeth with grade II mobility after periodontal therapy.This study was designed as a retrospective cohort study, conducted among patients who reported to the university dental hospital. Subjects above 18 years of age, subjects who underwent periodontal therapy in tooth with grade II mobility, and completed at least a six month followup evaluation were included in this study. Smokers, medically compromised patients were excluded from this study. -

Long-Term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: a Case Report

Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report Abstract Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition characterized by varying degrees of gingival hyperplasia. Gingival fibromatosis usually occurs as an isolated disorder or can be associated with a variety of other syndromes. A 33-year-old male patient who had a generalized severe gingival overgrowth covering two thirds of almost all maxillary and mandibular teeth is reported. A mucoperiosteal flap was performed using interdental and crevicular incisions to remove excess gingival tissues and an internal bevel incision to reflect flaps. The patient was treated 15 years ago in the same clinical facility using the same treatment strategy. There was no recurrence one year following the most recent surgery. Keywords: Gingival hyperplasia, hereditary gingival hyperplasia, HGF, hereditary disease, therapy, mucoperiostal flap Citation: S¸engün D, Hatipog˘lu H, Hatipog˘lu MG. Long-term Uncontrolled Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis: A Case Report. J Contemp Dent Pract 2007 January;(8)1:090-096. © Seer Publishing 1 The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, Volume 8, No. 1, January 1, 2007 Introduction Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF), also Ankara, Turkey with a complaint of recurrent known as elephantiasis gingiva, hereditary generalized gingival overgrowth. The patient gingival hyperplasia, idiopathic fibromatosis, had presented himself for examination at the and hypertrophied gingival, is a rare condition same clinic with the same complaint 15 years (1:750000)1 which can present as an isolated ago. At that time, he was treated with full-mouth disorder or more rarely as a syndrome periodontal surgery after the diagnosis of HGF component.2,3 This condition is characterized by had been made following clinical and histological a slow and progressive enlargement of both the examination (Figures 1 A-B). -

Guideline # 18 ORAL HEALTH

Guideline # 18 ORAL HEALTH RATIONALE Dental caries, commonly referred to as “tooth decay” or “cavities,” is the most prevalent chronic health problem of children in California, and the largest single unmet health need afflicting children in the United States. A 2006 statewide oral health needs assessment of California kindergarten and third grade children conducted by the Dental Health Foundation (now called the Center for Oral Health) found that 54 percent of kindergartners and 71 percent of third graders had experienced dental caries, and that 28 percent and 29 percent, respectively, had untreated caries. Dental caries can affect children’s growth, lead to malocclusion, exacerbate certain systemic diseases, and result in significant pain and potentially life-threatening infections. Caries can impact a child’s speech development, learning ability (attention deficit due to pain), school attendance, social development, and self-esteem as well.1 Multiple studies have consistently shown that children with low socioeconomic status (SES) are at increased risk for dental caries.2,3,4 Child Health Disability and Prevention (CHDP) Program children are classified as low socioeconomic status and are likely at high risk for caries. With regular professional dental care and daily homecare, most oral disease is preventable. Almost one-half of the low-income population does not obtain regular dental care at least annually.5 California children covered by Medicaid (Medi-Cal), ages 1-20, rank 41 out of all 50 states and the District of Columbia in receiving any preventive dental service in FY2011.6 Dental examinations, oral prophylaxis, professional topical fluoride applications, and restorative treatment can help maintain oral health. -

Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters

microorganisms Article Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters Andrea Butera , Simone Gallo * , Carolina Maiorani, Domenico Molino, Alessandro Chiesa, Camilla Preda, Francesca Esposito and Andrea Scribante * Section of Dentistry–Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Paediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (F.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Periodontitis consists of a progressive destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. Considering that probiotics are being proposed as a support to the gold standard treatment Scaling-and-Root- Planing (SRP), this study aims to assess two new formulations (toothpaste and chewing-gum). 60 patients were randomly assigned to three domiciliary hygiene treatments: Group 1 (SRP + chlorhexidine-based toothpaste) (control), Group 2 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste) and Group 3 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste + probiotics-based chewing-gum). At baseline (T0) and after 3 and 6 months (T1–T2), periodontal clinical parameters were recorded, along with microbiological ones by means of a commercial kit. As to the former, no significant differences were shown at T1 or T2, neither in controls for any index, nor in the experimental -

Management of Acute Periodontal Abscess Mimicking Acute Apical Abscess in the Anterior Lingual Region: a Case Report

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.5592 Management of Acute Periodontal Abscess Mimicking Acute Apical Abscess in the Anterior Lingual Region: A Case Report Omar A. Alharbi 1 , Muhammad Zubair Ahmad 1 , Atif S. Agwan 1 , Durre Sadaf 1 1. Conservative Dentistry, Qassim University, College of Dentistry, Buraydha, SAU Corresponding author: Muhammad Zubair Ahmad, [email protected] Abstract Purulent infections of periodontal tissues are known as periodontal abscesses localized to the region of the involved tooth. Due to the high prevalence rate and aggressive symptoms, it is considered a dental emergency; urgent care is mandatory to maintain the overall health and well being of the patient. This case report describes the management of a patient who presented with an acute periodontal abscess secondary to poor oral hygiene. Clinically and radiographically, the lesion was mimicking an acute apical abscess secondary to pulpal necrosis. Periodontal treatment was started after completion of antibiotic therapy. The clinical presentation of the condition and results of the recovery, along with a brief review of relevant literature are discussed. Categories: Pain Management, Miscellaneous, Dentistry Keywords: periodontal abscess, antimicrobial agents, dental pulp test, dental pulp necrosis, apical suppurative periodontitis Introduction Periodontium, as a general term, describes the tissues surrounding and supporting the tooth structure. A localized purulent infection of the periodontal tissues adjacent to a periodontal pocket, also known as a periodontal abscess, is a frequently encountered periodontal condition that may be characterized by the rapid destruction of periodontal tissues [1-2]. The symptoms generally involve severe pain, swelling of the alveolar mucosa or gingiva, a reddish blue or red appearance of the affected tissues, and difficulty in chewing [1-3]. -

Cytokines and Their Genetic Polymorphisms Related to Periodontal Disease

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Cytokines and Their Genetic Polymorphisms Related to Periodontal Disease Małgorzata Kozak 1, Ewa Dabrowska-Zamojcin 2, Małgorzata Mazurek-Mochol 3 and Andrzej Pawlik 4,* 1 Chair and Department of Dental Prosthetics, Pomeranian Medical University, Powsta´nców Wlkp 72, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmacology, Pomeranian Medical University, Powsta´nców Wlkp 72, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Periodontology, Pomeranian Medical University, Powsta´nców Wlkp 72, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department of Physiology, Pomeranian Medical University, Powsta´nców Wlkp 72, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 October 2020; Accepted: 10 December 2020; Published: 14 December 2020 Abstract: Periodontal disease (PD) is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by the accumulation of bacterial plaque biofilm on the teeth and the host immune responses. PD pathogenesis is complex and includes genetic, environmental, and autoimmune factors. Numerous studies have suggested that the connection of genetic and environmental factors induces the disease process leading to a response by both T cells and B cells and the increased synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines. Many studies have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines play a significant role in the pathogenesis of PD. The studies have also indicated that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in cytokine genes may be associated with risk and severity of PD. In this narrative review, we discuss the role of selected cytokines and their gene polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Keywords: periodontal disease; cytokines; polymorphism 1. -

02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix a to Rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01

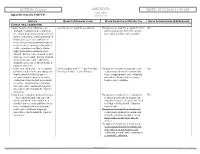

ACTION: Original AMENDED DATE: 02/23/2018 11:54 AM Appendix Appendix A to rule 5160-5-01 5160-5-01 SERVICE QUANTITY/FREQUENCY LIMIT OTHER CONDITION OR RESTRICTION PRIOR AUTHORIZATION (PA) REQUIRED CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION Comprehensive oral evaluation – A 1 per 5 years per provider per patient No payment is made for a comprehensive No thorough evaluation and recording of oral evaluation performed in conjunc- the extraoral and intraoral hard and soft tion with a periodic oral evaluation. tissues, it includes a dental and medical history and a general health assess- ment. It may encompass such matters as dental caries, missing or unerupted teeth, restorations, occlusal relation- ships, periodontal conditions, peri- odontal charting, tissue anomalies, and oral cancer screening. Interpretation of information may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Periodic oral evaluation – An evaluation Patient younger than 21: 1 per 180 days No payment is made for a periodic oral No performed to determine any changes in Patient 21 or older: 1 per 365 days evaluation performed in conjunction dental and medical health since a with a comprehensive oral evaluation previous comprehensive or periodic nor within 180 days after a compre- evaluation, it may include periodontal hensive oral evaluation. screening. Interpretation of informa- tion may require additional diagnostic procedures, which should be reported separately. Limited oral evaluation, problem-focused No payment is made if the evaluation is No – An evaluation limited to a specific performed solely for the purpose of oral health problem or complaint, it adjusting dentures, except as specified includes any necessary palliative treat- in Chapter 5160-28 of the Adminis- ment. -

Lateral Periodontal Cysts: a Retrospective Study of 11 Cases

Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008 May1;13(5):E313-7. Lateral periodontal cyst Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008 May1;13(5):E313-7. Lateral periodontal cyst Lateral periodontal cysts: A retrospective study of 11 cases María Florencia Formoso Senande 1, Rui Figueiredo 2, Leonardo Berini Aytés 3, Cosme Gay Escoda 4 (1) Resident of the Master of Oral Surgery and Implantology. University of Barcelona Dental School (2) Associate Professor of Oral Surgery. Professor of the Master of Oral Surgery and Implantology. University of Barcelona Dental School (3) Professor of Oral Surgery. Professor of the Master of Oral Surgery and Implantology. Dean of the University of Barcelona Dental School (4) Chairman of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Director of the Master of Oral Surgery and Implantology. University of Barcelona Dental School. Oral and maxillofacial surgeon of the Teknon Medical Center, Barcelona (Spain) Correspondence: Prof. Cosme Gay Escoda Centro Médico Teknon C/ Vilana 12 08022 – Barcelona (Spain) E-mail: [email protected] Formoso-Senande MF, Figueiredo R, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C. Received: 20/04/2007 Lateral periodontal cysts: A retrospective study of 11 cases. Med Oral Accepted: 29/03/2008 Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008 May1;13(5):E313-7. © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - ISSN 1698-6946 http://www.medicinaoral.com/medoralfree01/v13i5/medoralv13i5p313.pdf Indexed in: -Index Medicus / MEDLINE / PubMed -EMBASE, Excerpta Medica -SCOPUS -Indice Médico Español -IBECS Abstract Objective: To describe the clinical, radiological and histopathological features of lateral periodontal cysts among patients diagnosed in different centers (Vall d’Hebron General Hospital, Granollers General Hospital, the Teknon Medical Center, and the Master of Oral Surgery and Implantology of the University of Barcelona Dental School; Barcelona, Spain). -

Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care Guidance in Brief

Scottish Dental SD Clinical Effectiveness Programme cep Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care Guidance in Brief June 2014 Scottish Dental SD Clinical Effectiveness Programme cep The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) is an initiative of the National Dental Advisory Committee (NDAC) in partnership with NHS Education for Scotland. The Programme provides user-friendly, evidence-based guidance on topics identified as priorities for oral health care. SDCEP guidance aims to support improvements in patient care by bringing together, in a structured manner, the best available information that is relevant to the topic and presenting this information in a form that can be interpreted easily and implemented. Supporting the provision of safe, effective, person-centred care Scottish Dental SD Clinical Effectiveness Programme cep Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care Guidance in Brief June 2014 Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care Cover image: Colour-enhanced photomicrograph of oral bacterial colonies growing on an agar plate. Derren Ready, Wellcome Images. © Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme SDCEP operates within NHS Education for Scotland. You may copy or reproduce the information in this document for use within NHS Scotland and for non-commercial educational purposes. Use of this document for commercial purposes is permitted only with written permission. ISBN 978 1 905829 18 7 Published June 2014 Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme Dundee Dental Education Centre, Frankland Building, Small’s Wynd, Dundee DD1 4HN Email [email protected] Tel 01382 425751 / 425771 Website www.sdcep.org.uk Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care Introduction Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care is designed to assist and support primary care dental teams in providing appropriate care for patients both at risk of and with periodontal diseases. -

Pediatric Oral Pathology. Soft Tissue and Periodontal Conditions

PEDIATRIC ORAL HEALTH 0031-3955100 $15.00 + .OO PEDIATRIC ORAL PATHOLOGY Soft Tissue and Periodontal Conditions Jayne E. Delaney, DDS, MSD, and Martha Ann Keels, DDS, PhD Parents often are concerned with “lumps and bumps” that appear in the mouths of children. Pediatricians should be able to distinguish the normal clinical appearance of the intraoral tissues in children from gingivitis, periodontal abnormalities, and oral lesions. Recognizing early primary tooth mobility or early primary tooth loss is critical because these dental findings may be indicative of a severe underlying medical illness. Diagnostic criteria and .treatment recommendations are reviewed for many commonly encountered oral conditions. INTRAORAL SOFT-TISSUE ABNORMALITIES Congenital Lesions Ankyloglossia Ankyloglossia, or “tongue-tied,” is a common congenital condition characterized by an abnormally short lingual frenum and the inability to extend the tongue. The frenum may lengthen with growth to produce normal function. If the extent of the ankyloglossia is severe, speech may be affected, mandating speech therapy or surgical correction. If a child is able to extend his or her tongue sufficiently far to moisten the lower lip, then a frenectomy usually is not indicated (Fig. 1). From Private Practice, Waldorf, Maryland (JED); and Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Dentistry, Duke Children’s Hospital, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MAK) ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ PEDIATRIC CLINICS OF NORTH AMERICA VOLUME 47 * NUMBER 5 OCTOBER 2000 1125 1126 DELANEY & KEELS Figure 1. A, Short lingual frenum in a 4-year-old child. B, Child demonstrating the ability to lick his lower lip. Developmental Lesions Geographic Tongue Benign migratory glossitis, or geographic tongue, is a common finding during routine clinical examination of children. -

A Panoramic View of Junctional Epithelium and Biologic Width Around Teeth and Implant

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 16, Issue 9 Ver. IX (September. 2017), PP 61-70 www.iosrjournals.org A Panoramic View of Junctional Epithelium And Biologic Width Around Teeth And Implant *Dr. Jaimini Patel1, Dr. Jasuma Rai2,Dr. Deepak Dave3,Dr. Nidhi Shah4, Dr. Shraddha Shah5 1,2,3,4,5,(Department of Periodontology/ K. M. Shah Dental College and Hospital/ Sumandeep Vidyapeeth, India) Corresponding Author: *Dr. Jaimini Patel Abstract : Junctional epithelium is the most dynamic feature of the periodontal tissues as it not only plays an important role in health but also displays various characteristic changes in disease. The biologic width around tooth and implants is also an important consideration from treatment point of view. In the following review we have discussed the importance of junctional epithelium and biologic width around teeth and implant and the factors that influence the peri-implant biologic width. Keywords : Biologic Width, Junctional Epithelium, Implant ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 29 -07-2017 Date of acceptance: 09-09-2017 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. Introduction Teeth are trans-mucosal organs. This is a unique association in the human body where a hard tissue emerges through the soft tissue. Epithelia exhibit considerable differences in their histology, thickness and differentiation suitable for the functional demands of their location.1 The gingival epithelium around a tooth is divided into three functional compartments– outer, sulcular, and junctional epithelium. The outer epithelium extends from the mucogingival junction to the gingival margin where crevicular/sulcular epithelium lines the sulcus. At the base of the sulcus connection between gingiva and tooth is mediated with junctional epithelium.