Toronto Slavic Quarterly. № 43. Winter 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Twilight Anton Chekhov

In the Twilight Anton Chekhov Translated by Hugh Aplin ALMA CLASSICS AlmA ClAssiCs ltd London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com In the Twilight first published in Russian in 1887 This translation first published by Alma Classics Ltd in 2014 Translation and Notes © Hugh Aplin, 1887 Extra Material © Alma Classics Ltd Cover image © Marina Rodrigues Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY isbn: 978-1-84749-383-5 All the pictures in this volume are reprinted with permission or pre sumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge their copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Introduction v In the Twilight 1 Dreams 3 A Trivial Occurrence 12 A Bad Business 23 At Home 29 The Witch 39 Verochka 53 In Court 67 A Restless Guest 75 The Requiem 82 On the Road 88 Misfortune 105 An Event 119 Agafya 125 Enemies 136 A Nightmare 150 On Easter Eve 165 Note on the Text 177 Notes 179 Extra Material 185 Anton Chekhov’s Life 187 Anton Chekhov’s Works 198 Select Bibliography 206 Introduction The early part of Anton Chekhov’s literary career was a period of frenzied writing. -

The Beginnings of the Art Colonies of Cape Ann, 1875-1925 Lecture Finding Aid & Transcript

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ART COLONIES OF CAPE ANN, 1875-1925 LECTURE FINDING AID & TRANSCRIPT Speaker: Mary Rhinelander McCarl Date: 5/28/2011 Runtime: 57:17 Camera Operator: Bob Quinn Identification: VL33; Video Lecture #33 Citation: McCarl, Mary Rhinelander. “The Beginnings of the Art Colonies of Cape Ann, 1875-1925.” CAM Video Lecture Series, 5/28/2011. VL33, Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Description: Karla Kaneb, 4/25/2020. Transcript: Heidi McGrath, 6/30/2020. Video Description Recorded in the gallery of the North Shore Arts Association in East Gloucester, this video captures a lecture by local historian and Cape Ann Museum volunteer Mary Rhinelander McCarl in which she speaks about the late 19th century art colonies that flourished on Cape Ann. Drawn by the picturesque, accessible, and relatively inexpensive setting, many artists began to gather in Gloucester during The Beginnings of the Art Colonies of Cape Ann, 1875-1923 – VL33 – page 2 this time from several metropolitan areas while locally born artists thrived as well. McCarl discusses the careers of a few who were instrumental in establishing the arts-focused tenor of neighborhoods such as Annisquam and Rocky Neck. Her list includes both men and women and is presented within the context of evolving social and political influences. Subject list George Wainwright Harvey William and Emmeline Atwood Martha Hale Rogers Harvey Mary Rhinelander McCarl John K. Thurston Magnolia Ellen Day Hale Annisquam Helen M. Knowlton Rocky Neck Augustus Buhler Red Cottage Walter Lofthouse Dean Gallery on the Moors Charles Allan Winter North Shore Arts Association Alice Beach Winter Gloucester Society of Artists William Morris Hunt Transcript Suzanne Gilbert 00:09 So, thank you everyone for coming this afternoon. -

1 THANK YOU M'am by LANGSTON HUGHES A. Answer Thes

CLASS 11 SUBJECT – ENGLISH Chapters 1, 2, 3, CHAPTER – 1 THANK YOU M'AM By LANGSTON HUGHES A. Answer these questions in 30 – 40 words. 1.What did the boy try to snatch? Answer : The boy tried to snatch the purse of Mrs Luella Bates Washington Jones to get money so that he can purchase blue suede shoes. 2.Why was he not successful in his attempt? Answer: He was not successful in his attempt because the strap of a purse broke with the single tug the boy gave it from behind. But the boy’s weight and the weight of the purse combined caused him to lose his balance. So, instead of running away as he had hoped, the boy fell on his back on the sidewalk, and his legs flew up. 3.What did the woman do in response? Answer: The large woman simply turned around and kicked him directly to his blue-jeaned sitter. Then she reached down, picked the boy up by his shirt front, and shook him until his teeth rattled 4.Why did the boy not run away when the woman finally let go of his neck? Answer: The boy did not run away when the woman finally let go of his neck because he realized his mistakes and he was sorry for the action he had done. Moreover, he was given second chance by the woman when she took him at her apartment rather than to the police. 5.Why was the boy trying to steal? Answer: The boy said that the reason behind his action of trying to steal the purse of the woman was because he wanted to buy a pair of blue suede shoes. -

The Best American Humorous Short

MY LIFE THE STORY OF A PROVINCIAL Anton Chekhov I THE Superintendent said to me: "I only keep you out of regard for your worthy father; but for that you would have been sent flying long ago." I replied to him: "You flatter me too much, your Excellency, in assuming that I am capable of flying." And then I heard him say: "Take that gentleman away; he gets upon my nerves." Two days later I was dismissed. And in this way I have, during the years I have been regarded as grown up, lost nine situations, to the great mortification of my father, the architect of our town. I have served in various departments, but all these nine jobs have been as alike as one drop of water is to another: I had to sit, write, listen to rude or stupid observations, and go on doing so till I was dismissed. When I came in to my father he was sitting buried in a low arm-chair with his eyes closed. His dry, emaciated face, with a shade of dark blue where it was shaved (he looked like an old Catholic organist), expressed meekness and resignation. Without responding to my greeting or opening his eyes, he said: "If my dear wife and your mother were living, your life would have been a source of continual distress to her. I see the Divine Providence in her premature death. I beg you, unhappy boy," he continued, opening his eyes, "tell me: what am I to do with you?" In the past when I was younger my friends and relations had known what to do with me: some of them used to advise me to volunteer for the army, others to get a job in a pharmacy, and others in the telegraph department; now that I am over twenty-five, that grey hairs are beginning to show on my temples, and that I have been already in the 1 army, and in a pharmacy, and in the telegraph department, it would seem that all earthly possibilities have been exhausted, and people have given up advising me, and merely sigh or shake their heads. -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

Matthew Herrald

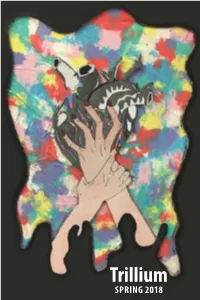

Trillium Issue 39, 2018 The Trillium is the literary and visual arts publication of the Glenville State College Department of Language and Literature Jacob Cline, Student Editor Heather Coleman, Art Editor Dr. Jonathan Minton, Faculty Advisor Dr. Marjorie Stewart, Co-Advisor Dustin Crutchfield, Designer Cover Artwork by Cearra Scott The Trillium welcomes submissions and correspondence from Glenville State College students, faculty, staff, and our extended creative community. Trillium Department of Language and Literature Glenville State College 200 High Street | Glenville, WV 26351 [email protected] http://www.glenville.edu/life/trillium.php The Trillium acquires printing rights for all published materials, which will also be digitally archived. The Trillium may use published artwork for promotional materials, including cover designs, flyers, and posters. All other rights revert to the authors and artists. POETRY Alicia Matheny 01 Return To Expression Jonathan Minton 02 from LETTERS Wayne de Rosset 03 Healing On the Way Brianna Ratliff 04 Untitled Matthew Herrald 05 Cursed Blood Jared Wilson 06 The Beast (Rise and Fall) Brady Tritapoe 09 Book of Knowledge Hannah Seckman 12 I Am Matthew Thiele 13 Stop Making Sense Logan Saho 15 Consequences Megan Stoffel 16 One Day Kerri Swiger 17 The Monsters Inside of Us Johnny O’Hara 18 This Love is Alive Paul Treadway 19 My Mistress Justin Raines 20 Patriotism Kitric Moore 21 The Day in the Life of a College Student Carissa Wood 22 7 Lives of a House Cat Hannah Curfman 23 Earth’s Pure Power Jaylin Johnson 24 Empty Chairs William T. K. Harper 25 Graffiti on the Poet Lauriat’s Grave Kristen Murphy 26 Mama Always Said Teddy Richardson 27 Flesh of Ash Randy Stiers 28 Fussell Said; Caroline Perkins 29 RICHWOOD Sam Edsall 30 “That Day” PROSE Teddy Richardson 33 The Fall of McBride Logan Saho 37 Untitled Skylar Fulton 39 Prayer Weeds David Moss 41 Hot Dogs Grow On Trees Hannah Seckman 42 Of Teeth Berek Clay 45 Lost Beach Sam Edsall 46 Black Magic 8-Ball ART Harold Reed 57 Untitled Maurice R. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre

The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre Florence Goyet THE CLASSIC SHORT STORY The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre Florence Goyet http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Florence Goyet This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that she endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Goyet, Florence. The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925: Theory of a Genre. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0039 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/199#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available on our website at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/199#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-75-6 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-76-3 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-77-0 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-78-7 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-79-4 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0039 Cover portraits (left to right): Henry James, Flickr Commons (http://www.flickr.com/photos/7167652@ N06/2871171944/), Guy de Maupassant, Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guy_ de_Maupassant_fotograferad_av_Félix_Nadar_1888.jpg), Giovanni Verga, Wikimedia (http:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catania_Giovanni_Verga.jpg), Anton Chekhov, Wikimedia (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anton_Chekov_1901.jpg) and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Akutagawa_Ryunosuke_photo.jpg). -

The Good Doctor: the Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (And Others)

Vol. 33, No. 1 11 Literature and the Arts in Medical Education Johanna Shapiro, PhD Feature Editor Editor’s Note: In this column, teachers who are currently using literary and artistic materials as part of their curricula will briefly summarize specific works, delineate their purposes and goals in using these media, describe their audience and teaching strategies, discuss their methods of evaluation, and speculate about the impact of these teaching tools on learners (and teachers). Submissions should be three to five double-spaced pages with a minimum of references. Send your submissions to me at University of California, Irvine, Department of Family Medicine, 101 City Drive South, Building 200, Room 512, Route 81, Orange, CA 92868-3298. 949-824-3748. Fax: 714-456- 7984. E-mail: [email protected]. The Good Doctor: The Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (and Others) Lawrence J. Schneiderman, MD In the spring of 1985, I posted a anything to do with me. “I don’t not possible in this public univer- notice on the medical students’ bul- want a doctor who knows Chekhov, sity; our conference rooms are best letin board announcing a new elec- I want a doctor who knows how to described as Bus Terminal Lite. tive course, “The Good Doctor: The take out my appendix.” Fortunately, The 10 second-year students who Literature and Medicine of Anton I was able to locate two more agree- signed up that first year spent 2 Chekhov.” It was a presumptuous able colleagues from literature and hours each week with me for 10 announcement, since I had never theatre. -

The Pacific War Crimes Trials: the Importance of the "Small Fry" Vs. the "Big Fish"

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Summer 2012 The aP cific aW r Crimes Trials: The mpI ortance of the "Small Fry" vs. the "Big Fish" Lisa Kelly Pennington Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pennington, Lisa K.. "The aP cific aW r Crimes Trials: The mporI tance of the "Small Fry" vs. the "Big Fish"" (2012). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/rree-9829 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PACIFIC WAR CRIMES TRIALS: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE "SMALL FRY" VS. THE "BIG FISH by Lisa Kelly Pennington B.A. May 2005, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2012 Approved by: Maura Hametz (Director) Timothy Orr (Member) UMI Number: 1520410 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

26 Gcean GROVE TIMES, TOWNSHIP of NEPTUNE, NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, Junii; 26, 19(I4 State to Dredge Imr

p The Family It Pays Newspaper To Advertise In The Times Vol. LXXXIX, No. 26 gCEAN GROVE TIMES, TOWNSHIP OF NEPTUNE, NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, JUNIi; 26, 19(i4 State To Dredge iMr. & Mrs. C. Leslie Severs, Si%, Invite CENTSw 1 In Shark ~ | String Band[ In iMr. and Mrs. Homer I). Kresge Feted Grove To Enforce Friends To 50th Wedding Reception Concert Opener - • ......... 1 On Golden Wedding Anniversary “Taste & Conduct” Township Receives Notice of $67,500 Project; Issue OCEAN GROVE— The first Temporary Sewer Notes concert of the season is sched - ; President TAsk^ Residents uled for tomorrow (Saturday) night at Sri5 at the Auditori & Vacationists To Observe •NBPTU-NE TWP. — The Now um when the Ferko String Kules of Deportment Jersey Department of Conservation , Hand of Philadelphia makes its and Economic Development notified! fifth annual appearance. The the. township committee Tuesday! prize - winning Mummers or OCEAN GROVE — The summer • night that the state plans a $07,500 | ganization will play and sing season is in full swing and .Ocean, maintenance 'dredging, project in, many popular numbers and (iruvu intends to observe its rules Shark: Uiv.ev, near the Shark River j display costumes which have o ..M'L’inifitr attire, dogs, bicycle rjd-V' •' Islands. No further details, of the f non top prizes in the Phila . :r», ..nil ocher deportm ent, accord ■ proposal were available. : ■ • delphia New Year’s Day cele ing to Dr. Charles 1. Carpenter, ; The'committee' authorized issil-! bration. l’i esident of the Ocean Grove Camp ... ance of $3,208,300 "in bond anticipa-1 Meet: ng Association. -

Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Author(S): Christopher Ely Source: Slavic Review, Vol

The Origins of Russian Scenery: Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Author(s): Christopher Ely Source: Slavic Review, Vol. 62, No. 4, Tourism and Travel in Russia and the Soviet Union, (Winter, 2003), pp. 666-682 Published by: The American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3185650 Accessed: 06/06/2008 13:39 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aaass. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org The Origins of Russian Scenery: Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Christopher Ely BoJira onrcaHo, nepeonicaHo, 4 Bce-TaKHHe AgoicaHo.