The Characterization of the Physician in Schnitzler's and Chekhov's Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mad-Cow’ Worries Intensify Becoming Prevalent.” Institute

The National Livestock Weekly May 26, 2003 • Vol. 82, No. 32 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication ‘Mad-cow’ worries intensify becoming prevalent.” Institute. “The (import) ban has but because the original diagnosis Canada has a similar feed ban to caused a lot of problems with our was pneumonia, the cow was put Canada what the U.S. has implemented. members and we’re hopeful for this on a lower priority list for testing. Under that ban, ruminant feeds situation to be resolved in very The provincial testing process reports first cannot contain animal proteins be- short order.” showed a possible positive vector North American cause they may contain some brain The infected cow was slaugh- for mad-cow and from there the and spinal cord matter, thought to tered January 31 and condemned cow was sent to a national testing BSE case. carry the prion causing mad-cow from the human food supply be- laboratory for a follow-up test. Fol- disease. cause of symptoms indicative of lowing a positive test there, the Beef Industry officials said due to pneumonia. That was the prima- test was then conducted by a lab Canada’s protocol regarding the ry reason it took so long for the cow in England, where the final de- didn’t enter prevention of mad-cow disease, to be officially diagnosed with BSE. termination is made on all BSE- food chain. they are hopeful this is only an iso- The cow, upon being con- suspect animals. -

Politics and Power in the Gothic Drama of MG Lewis

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES School of Humanities Politics and Power in the Gothic Drama of M.G. Lewis By Rachael Pearson Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 1 2 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy POLITICS AND POWER IN THE GOTHIC DRAMA OF M.G. LEWIS Rachael Pearson Matthew Lewis‟s 1796 novel The Monk continues to attract critical attention, but the accusation that it was blasphemous has overshadowed the rest of his writing career. He was also a playwright, M. P. and slave-owner. This thesis considers the need to reassess the presentation of social power, primarily that of a conservative paternalism, in Lewis‟s dramas and the impact of biographical issues upon this. -

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (To Be Confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (to be confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS TSM,SH SS TSM, SH Optional/Mandatory Optional Semester(s) MT Contact hour per week 2 contact hours/week; total 22 hours Private study (hours per week) 100 hours Lecturer(s) Justin Doherty ECTs 10 ECTs Aims This module surveys Chekhov’s writing in both short-story and dramatic forms. While some texts from Chekhov’s early period will be included, the focus will be on works from the later 1880s, 1890s and early 1900s. Attention will be given to the social and historical circumstances which form the background to Chekhov’s writings, as well as to major influences on Chekhov’s writing, notably Tolstoy. In examining Chekhov’s major plays, we will also look closely at Chekhov’s involvement with the Moscow Arts Theatre and theatre director and actor Konstantin Stanislavsky. Set texts will include: 1. Short stories ‘Rural’ narratives: ‘Steppe’, ‘Peasants’, ‘In the Ravine’ Psychological stories: ‘Ward No 6’, ‘The Black Monk’, ‘The Bishop’, ‘A Boring Story’ Stories of gentry life: ‘House with a Mezzanine’, ‘The Duel’, ‘Ariadna’ Provincial stories: ‘My Life’, ‘Ionych’, ‘Anna on the Neck’, ‘The Man in a Case’ Late ‘optimistic’ stories: ‘The Lady with the Dog’, ‘The Bride’ 2. Plays The Seagull Uncle Vanya Three Sisters The Cherry Orchard Note on editions: for the stories, I recommend the Everyman edition, The Chekhov Omnibus: Selected Stories, tr. Constance Garnett, revised by Donald Rayfield, London: J. M. Dent, 1994. There are numerous other translations e.g. -

March 22, 2018

Packer Lambs Steady To Mostly Lower San Angelo slaughter lamb prices were $10-20 lower this week, feeder lambs steady. Goldthwaite wool lambs were $5 lower, light Dorper and Bar- bado lambs $5-10 lower, and medium and heavy hair lambs steady to $5 lower. Hamilton lambs sold steady. Fredericks- burg lambs were $5 lower. VOL. 70 - NO. 11 SAN ANGELO, TEXAS THURSDAY, MARCH 22, 2018 LIVESTOCKWEEKLY.COM $35 PER YEAR Lamb and mutton meat production for the week end- ing March 16 totaled three million pounds on a slaugh- ter count of 40,000 head compared with the previous week’s totals of 3.1 million pounds and 42,000 head. Imported lamb and mutton for the week ending March 10 totaled 2553 metric tons or approximately 5.63 million pounds, equal to 182 percent of domestic production for the same period. San Angelo’s feeder lamb market had medium and large 1-2 newcrop lambs weighing 40-60 pounds at $200-206, 60-90 pounds $192-218, 80- 100 pounds $192-218, oldcrop 60-90 pounds $184-196, and 100-105 pounds $166-172. Fredericksburg No. 1 wool lamb weighing 40-60 pounds were $200-240 and 60-80 pounds $200-230. Hamil- ton Dorper and Dorper cross lambs weighing 20-40 pounds sold for $180-260. Direct trade on feeder lambs last week was limited to Colo- rado, where 400 head weighing SOCIAL WARRIORS may take offense, but males-only 125-135 pounds brought $168. enclaves are still common in the livestock business. San Angelo choice 2-3 Whether bucks, bulls or billies, the Old Boys’ clubs are slaughter lambs weighing Range Sales a fi xture much of the year, giving way only during breed- 110-170 pounds brought ing season, itself a highly non-PC concept. -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

The Good Doctor: the Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (And Others)

Vol. 33, No. 1 11 Literature and the Arts in Medical Education Johanna Shapiro, PhD Feature Editor Editor’s Note: In this column, teachers who are currently using literary and artistic materials as part of their curricula will briefly summarize specific works, delineate their purposes and goals in using these media, describe their audience and teaching strategies, discuss their methods of evaluation, and speculate about the impact of these teaching tools on learners (and teachers). Submissions should be three to five double-spaced pages with a minimum of references. Send your submissions to me at University of California, Irvine, Department of Family Medicine, 101 City Drive South, Building 200, Room 512, Route 81, Orange, CA 92868-3298. 949-824-3748. Fax: 714-456- 7984. E-mail: [email protected]. The Good Doctor: The Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (and Others) Lawrence J. Schneiderman, MD In the spring of 1985, I posted a anything to do with me. “I don’t not possible in this public univer- notice on the medical students’ bul- want a doctor who knows Chekhov, sity; our conference rooms are best letin board announcing a new elec- I want a doctor who knows how to described as Bus Terminal Lite. tive course, “The Good Doctor: The take out my appendix.” Fortunately, The 10 second-year students who Literature and Medicine of Anton I was able to locate two more agree- signed up that first year spent 2 Chekhov.” It was a presumptuous able colleagues from literature and hours each week with me for 10 announcement, since I had never theatre. -

OSLO Casting Announcement

MICHAEL ARONOV, ADAM DANNHEISSER, JENNIFER EHLE, DANIEL JENKINS, DARIUSH KASHANI, JEFFERSON MAYS, DANIEL ORESKES, HENNY RUSSELL, JOSEPH SIRAVO, T. RYDER SMITH TO BE FEATURED IN THE LINCOLN CENTER THEATER PRODUCTION OF “OSLO” a new play by J.T. ROGERS directed by BARTLETT SHER PREVIEWS BEGIN THURSDAY, JUNE 16 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, JULY 11 AT THE MITZI E. NEWHOUSE THEATER Lincoln Center Theater (under the direction of André Bishop) has announced that Michael Aronov, Adam Dannheisser, Jennifer Ehle, Daniel Jenkins, Dariush Kashani, Jefferson Mays, Daniel Oreskes, Henny Russell, Joseph Siravo, and T. Ryder Smith will be featured in the cast of its upcoming production of OSLO, a new play by J.T. Rogers, directed by Bartlett Sher. Commissioned by Lincoln Center Theater, OSLO begins performances Thursday, June 16 and will open Monday, July 11 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater (150 West 65 Street). Additional casting will be announced at a later date. It’s 1993. The world watches the impossible: Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat, standing together in the White House Rose Garden, signing the first ever peace agreement between Israel and the PLO. How were the negotiations kept secret? Why were they held in a castle in the middle of Norway? And who are these mysterious negotiators? A darkly comic epic, OSLO tells the true, but until now, untold story of how one young couple, Norwegian diplomat Mona Juul (to be played by Jennifer Ehle) and her husband social scientist Terje Rød-Larsen (to be played by Jefferson Mays), planned and orchestrated top-secret, high-level meetings between the State of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, which culminated in the signing of the historic 1993 Oslo Accords. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

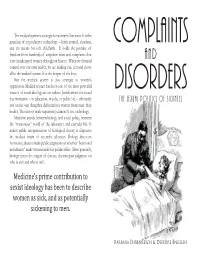

Complaints and Disorders

The medical system is strategic for women’s liberation. It is the guardian of reproductive technology – birth control, abortion, and the means for safe childbirth. It holds the promise of Complaints freedom from hundreds of unspoken fears and complaints that have handicapped women throughout history. When we demand AND control over our own bodies, we are making that demand above all to the medical system. It is the keeper of the keys. But the medical system is also strategic to women’s oppression. Medical science has been one of the most powerful sources of sexist ideology in our culture. Justifi cations for sexual Disorders discrimination – in education, in jobs, in public life – ultimately The Sexual Politics of Sickness rest on the one thing that differentiates women from men: their bodies. Theories of male superiority ultimately rest on biology. Medicine stands between biology and social policy, between the “mysterious” world of the laboratory and everyday life. It makes public interpretations of biological theory; it dispenses the medical fruits of scientifi c advances. Biology discovers hormones; doctors make public judgments on whether “hormonal unbalances” make women unfi t for public offi ce. More generally, biology traces the origins of disease; doctors pass judgment on who is sick and who is well. Medicine’s prime contribution to sexist ideology has been to describe women as sick, and as potentially sickening to men. Barbara Ehrenreich & Deirdre English Tacoma, WA This pamphlet was originally copyrighted in 1973. However, the distributors of this zine feel that important [email protected] information such as this should be shared freely. -

Flappers and Philosophers

1 Redacted by Curtis A. Weyant {[email protected]} Courtesy of the Michigan State University Libraries (http://digital.lib.msu.edu/) FLAPPERS AND PHILOSOPHERS F. SCOTT FITZGERALD To Zelda Contents The Offshore Pirate The Ice Palace Head and Shoulders The Cut-Glass Bowl Bernice Bobs Her Hair Benediction 2 Dalyrimple Goes Wrong The Four Fists Flappers and Philosophers The Offshore Pirate I This unlikely story begins on a sea that was a blue dream, as colorful as blue-silk stockings, and beneath a sky as blue as the irises of children's eyes. From the western half of the sky the sun was shying little golden disks at the sea--if you gazed intently enough you could see them skip from wave tip to wave tip until they joined a broad collar of golden coin that was collecting half a mile out and would eventually be a dazzling sunset. About half-way between the Florida shore and the golden collar a white steam-yacht, very young and graceful, was riding at anchor and under a blue-and-white awning aft a yellow-haired girl reclined in a wicker settee reading The Revolt of the Angels, by Anatole France. She was about nineteen, slender and supple, with a spoiled alluring mouth and quick gray eyes full of a radiant curiosity. Her feet, stockingless, and adorned rather than clad in blue-satin slippers which swung nonchalantly from her toes, were perched on the arm of a settee adjoining the one she occupied. And as she read she intermittently regaled herself by a faint application to her tongue of a half-lemon that she held in her hand.