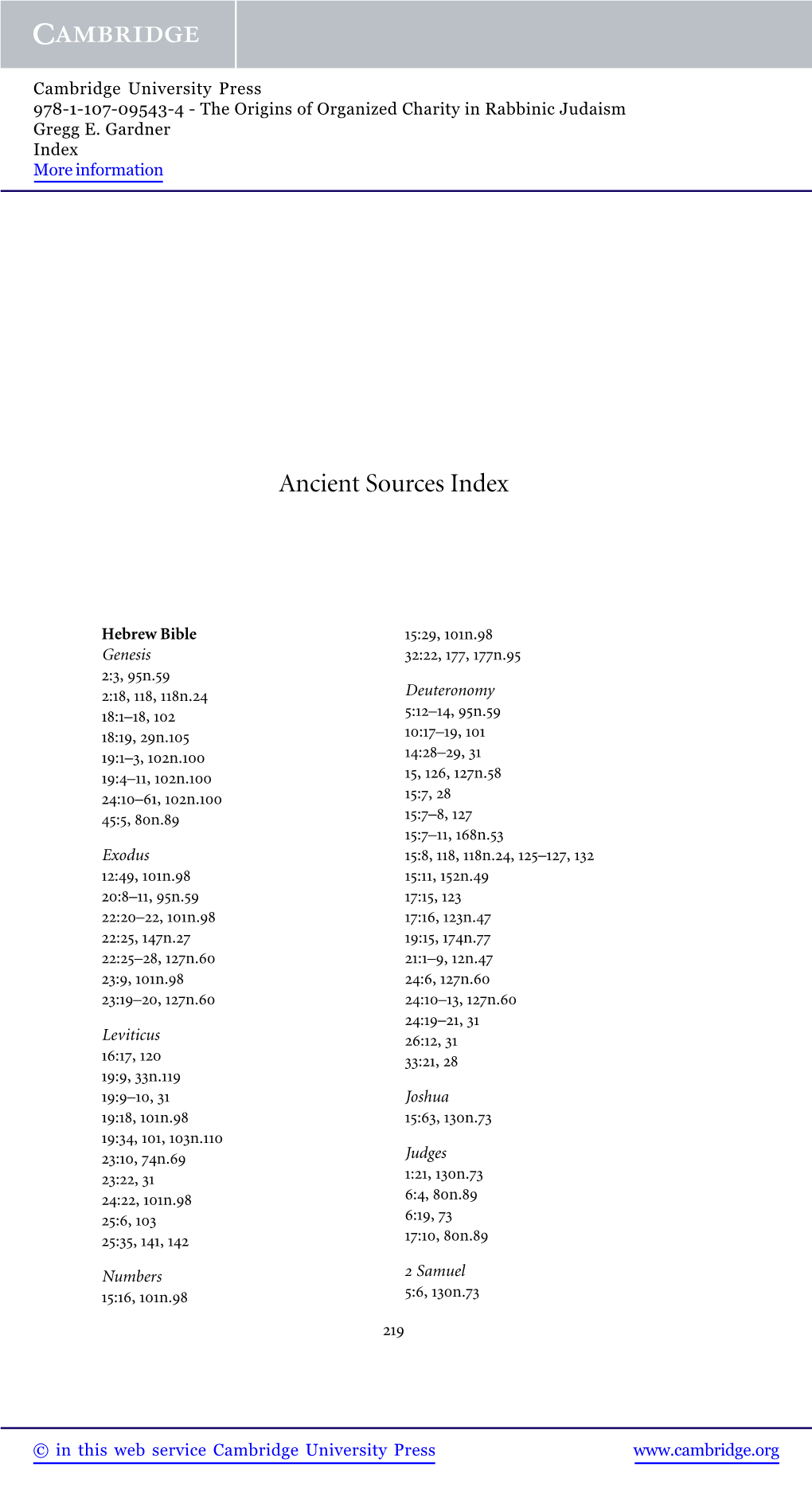

Ancient Sources Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Reassessing the Judean Desert Caves: Libraries, Archives, Genizas and Hiding Places

Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 2007 Volume 25 Reassessing the Judean Desert Caves: Libraries, Archives, Genizas and Hiding Places STEPHEN PFANN In December 1952, five years after the discovery of Qumran cave 1, Roland de Vaux connected its manuscript remains to the nearby site of Khirbet Qumran when he found one of the unique cylindrical jars, typical of cave 1Q, embedded in the floor of the site. The power of this suggestion was such that, from that point on, as each successive Judean Desert cave containing first-century scrolls was discovered, they, too, were assumed to have originated from the site of Qumran. Even the scrolls discovered at Masada were thought to have arrived there by the hands of Essene refugees. Other researchers have since proposed that certain teachings within the scrolls of Qumran’s caves provide evidence for a sect that does not match that of the Essenes described by first-century writers such as Josephus, Philo and Pliny. These researchers prefer to call this group ‘the Qumran Community’, ‘the Covenanters’, ‘the Yahad ’ or simply ‘sectarians’. The problem is that no single title sufficiently covers the doctrines presented in the scrolls, primarily since there is a clear diversity in doctrine among these scrolls.1 In this article, I would like to present a challenge to this monolithic approach to the understanding of the caves and their scroll collections. This reassessment will be based on a close examination of the material culture of the caves (including ceramics and fabrics) and the palaeographic dating of the scroll collections in individual caves. -

The Qumran Collection As a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sidnie White Crawford Publications Classics and Religious Studies 2016 The Qumran Collection as a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/crawfordpubs This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sidnie White Crawford Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Qumran Collection as a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford Since the early days of Dead Sea Scrolls scholarship, the collection of scrolls found in the eleven caves in the vicinity of Qumran has been identified as a library.1 That term, however, was undefined in relation to its ancient context. In the Greco-Roman world the word “library” calls to mind the great libraries of the Hellenistic world, such as those at Alexandria and Pergamum.2 However, a more useful comparison can be drawn with the libraries unearthed in the ancient Near East, primarily in Mesopotamia but also in Egypt.3 These librar- ies, whether attached to temples or royal palaces or privately owned, were shaped by the scribal elite of their societies. Ancient Near Eastern scribes were the literati in a largely illiterate society, and were responsible for collecting, preserving, and transmitting to future generations the cultural heritage of their peoples. In the Qumran corpus, I will argue, we see these same interests of collection, preservation, and transmission. Thus I will demonstrate that, on the basis of these comparisons, the Qumran collection is best described as a library with an archival component, shaped by the interests of the elite scholar scribes who were responsible for it. -

The Impact of the Documentary Papyri from the Judaean Desert on the Study of Jewish History from 70 to 135 CE

Hannah M. Cotton The Impact of the Documentary Papyri from the Judaean Desert on the Study of Jewish History from 70 to 135 CE We are now in possession of inventories of almost the entire corpus of documents discovered in the Judaean Desert1. Obviously the same cannot be said about the state of publication of the documents. We still lack a great many documents. I pro- pose to give here a short review of those finds which are relevant to the study of Jewish history between 70 and 135 CE. The survey will include the state of publi- cation of texts from each find2. After that an attempt will be made to draw some interim, and necessarily tentative, conclusions about the contribution that this fairly recent addition to the body of our evidence can make to the study of differ- ent aspects of Jewish history between 70 and 135 CE. This material can be divided into several groups: 1) The first documents came from the caves of Wadi Murabba'at in 1952. They were published without much delay in 19613. The collection consists of docu- ments written in Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Arabic, and contains, among 1 For a complete list till the Arab conquest see Hannah M. Cotton, Walter Cockle, Fergus Millar, The Papyrology of the Roman Near East: A Survey, in: JRS 85 (1995) 214-235, hence- forth Cotton, Cockle, Millar, Survey. A much shorter survey, restricted to the finds from the Judaean Desert, can be found in Hannah M. Cotton, s.v. Documentary Texts, in: Encyclo- pedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, eds. -

Another Document from the Archive of Salome Komaïse Daughter of Levi*

Another Document from the Archive of Salome Komaïse Daughter of Levi* Hanan Eshel The Babatha archive has been known since 1962.1 Not so the archive of Salome Ko- maïse daughter of Levi, who, like the famous Babatha, lived in Maúoz Eglatain (Maúoza), a village near Zoar, at the southern tip of the Dead Sea in what used to be the Nabataean Kingdom and in 106 became the Roman province of Arabia. She too de- parted from Arabia during the Bar Kokhba revolt, and she too hid her documents in the Cave of Letters in Naúal îever. Salome’s archive became known only in 1995.2 In the final publication the archive comprises seven documents,3 one in Aramaic (P.Hever 12) and six in Greek (P.Hever 60-65). The seven documents range from 29 January 125 CE (P.Hever 60) to 7 August 131 CE (P.Hever 65). On the other hand, the Babatha archive contains, in addition to documents in Greek (P.Yadin 5, 11-36) and Jewish Aramaic (P.Yadin 4, 7-8, 10) documents in Nabataean Aramaic (P.Yadin 1-3, 6 and 9) as well, and ranges from 10 September 94 CE (P.Yadin 1) to 19 August 132 CE (P.Yadin 27). There is no doubt that the Salome archive comes from the Cave of Letters, although like the rest of the so-called Seiy‰l Collection II — and unlike the Babatha archive — it was not found in the course of controlled excavations.4 In fact Yigael Yadin’s expedi- tion to the ‘Cave of Letters’ in 1961 discovered Salome Komaïse’s marriage contract (P.Hever 65) in the passageway between hall B and hall C, where the Beduin are likely * I should like to thank the editors for improving my text. -

Storage Conditions and Physical Treatments Relating to the Dating of the Dead Sea Scrolls

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 37, No. 1, 1995, P. 21-32] STORAGE CONDITIONS AND PHYSICAL TREATMENTS RELATING TO THE DATING OF THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS NICCOLO CALDARARO Department of Anthropology, San Francisco State University 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, California 94132 USA ABSTRACT. The Dead Sea Scrolls have been analyzed by paleographic, non-destructive and destructive testing. The dates of their creation have been in dispute since their discovery. Research has established their authenticity, but a variety of con- ditions including the methods of skin preparation, variation in storage conditions and post-discovery restoration treatments could have introduced changes now affecting dating efforts. Comprehensive analyses were not possible until recently. Such analysis must be performed to establish a concrete framework for all the texts. Professor R. B. Blake told a story in response to a question of why so little remained of writing on leather. He said that on one of his expedi- tions to Asia Minor, one of his native servants exhibited proudly some chamois trousers of his own manufacture, upon which Professor Blake detected with sorrow, traces of medieval writing (Reed 1972). INTRODUCTION A recent 14C study of 14 Dead Sea Scrolls by Bonani et al. (1992) is a welcome addition to the ana- lytical literature on the Scrolls. The authors have undertaken a more comprehensive sampling than any previous study, an effort that T. B. Kahle and I proposed in an article in Nature in 1986. In that article, we commented on amino acid racemization analysis of the Dead Sea Scrolls published by Weiner et al. (1980). Our comments then, as mine now, relate to the potential effects on dating results of prior storage conditions and restoration treatments. -

Three New Fragments from Qumran Cave 11*

THREE NEW FRAGMENTS FROM QUMRAN CAVE 11* HANAN ESHEL Bar-Ilan University S. Talmon recently published three fragments of scrolls that had been kept in Yigael YadinÕs desk drawer. 1 Although Talmon could not identify the scrolls from which these fragments came, he speculated that they might have been discovered in Qumran or in Na½al ¼ever. 2 We know that Yadin succeeded in purchasing several important scroll fragments from Khalil Iskander Shahin (Kando) that had been found in Qumran Cave 11. 3 Documents from the period of the Bar Kokhba revolt that Yadin had acquired in the antiquities market and kept in his desk drawer were published after his death. 4 The new fragments *This is a revision of a paper read at the Skirball Symposium on the Dead Sea Scrolls at New York University in October 1998. 1 S. Talmon, ÒUnidenti ed Hebrew Fragments from Y. YadinÕs Nachlass,Ó Tarbiz 66 (1996) 113-21 (Heb.); S. Talmon, ÒFragments of Hebrew Writings without Iden- tifying Sigla of Provenance from the Literary Legacy of Yigael Yadin,Ó DSD 5 (1998) 149-57. 2 Talmon notes the possibility that the rst fragment may have been discovered in Cave 32, which is located in Na½al Ñe¾elim and not in Na½al ¼ever (ÒUnidenti ed Hebrew Fragments,Ó 116). 3 Yadin purchased a fragment of the Cave 11 Psalms Scroll (frag. E) (see Y. Yadin, ÒAnother Fragment [E] of the Psalms Scroll from Qumran Cave 11 [11QPs a],Ó Textus 5 [1996] 1-10) and, of course, the Temple Scroll as well, which all scholars agree was discovered in Cave 11; see Y. -

Hanan Eshel - List of Publications

Hanan Eshel - List of Publications Books and Monographs 1. With D. Amit. The Bar-Kokhba Refuge Caves. Tel Aviv: Israel Exploration Society, 1998 (Hebrew). 2. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonaean State. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2004 (Hebrew). 3. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans and Yad Ben-Zvi, 2008. 4. Qumran: Scrolls, Caves and History, A Carta Field Guide, Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 5. Qumran: Scrolls, Caves and History, A Carta Field Guide, Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew). 6. Masada: An Epic Story, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 7. Masada: An Epic Story, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew) 8. Ein Gedi: Oasis and Refuge, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 9. Ein Gedi: Oasis and Refuge, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew). 10. With R. Porat. Refuge Caves of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Jerusalem, Israel Exploration Society, 2009 (Hebrew). 11. Editor with D. Amit. The Hasmonean State. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 1995 (Hebrew). 12. Editor with J. Charlesworth, N. Cohen, H. Cotton, E. Eshel, P. Flint, H. Misgav, M. Morgenstern, K. Murphy, M. Segal, A. Yardeni and B. Zissu, Miscellaneous Texts from the Judaean Desert, DJD 38. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. 13. Editor with B. Zissu. New Studies on the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Proceedings of the 21th Annual Conference of the Department of Land of Israel Studies, Ramat Gan: Department of Land of Israel Studies, 2001 (Hebrew). 14. Editor with E. Stern. The Samaritans. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2002 (Hebrew). 15. Editor with A.I. -

1 REFERENCES Abel M. 1903. Inscriptions Grecques De

1 REFERENCES Abel M. 1903. Inscriptions grecques de Bersabée. RB 12:425–430. Abel F.M. 1926. Inscription grecque de l’aqueduc de Jérusalem avec la figure du pied byzantin. RB 35:284–288. Abel F.M. 1941. La liste des donations de Baîbars en Palestine d’après la charte de 663H. (1265). JPOS 19:38–44. Abela J. and Pappalardo C. 1998. Umm al-Rasas, Church of St. Paul: Southeastern Flank. LA 48:542–546. Abdou Daoud D.A. 1998. Evidence for the Production of Bronze in Alexandria. In J.-Y. Empereur ed. Commerce et artisanat dans l’Alexandrie hellénistique et romaine (Actes du Colloque d’Athènes, 11–12 décembre 1988) (BCH Suppl. 33). Paris. Pp. 115–124. Abu-Jaber N. and al Sa‘ad Z. 2000. Petrology of Middle Islamic Pottery from Khirbat Faris, Jordan. Levant 32:179–188. Abulafia D. 1980. Marseilles, Acre and the Mediterranean, 1200–1291. In P.W. Edbury and D.M. Metcalf eds. Coinage in the Latin West (BAR Int. S. 77). Oxford. Pp. 19– 39. Abu l’Faraj al-Ush M. 1960. Al-fukhar ghair al-mutli (The Unglazed Pottery). AAS 10:135–184 (Arabic). Abu Raya R. and Weissman M. 2013. A Burial Cave from the Roman and Byzantine Periods at ‘En Ya‘al, Jerusalem. ‘Atiqot 76:11*–14* (Hebrew; English summary, pp. 217). Abu Raya R. and Zissu B. 2000. Burial Caves from the Second Temple Period on Mount Scopus. ‘Atiqot 40:1*–12* (Hebrew; English summary, p. 157). Abu-‘Uqsa H. 2006. Kisra. ‘Atiqot 53:9*–19* (Hebrew; English summary, pp. -

Tel Anafa II

Tel Anafa II, iii Sponsors: The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor The Museum of Art and Archaeology of the University of Missouri–Columbia The National Endowment for the Humanities The Smithsonian Institution Copyright © 2018 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology 434 South State Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1390, USA ISBN 978-0-9906623-8-9 KELSEY MUSEUM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN MUSEUM OF ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI–COLUMBIA TEL ANAFA II, iii Decorative Wall Plaster, Objects of Personal Adornment and Glass Counters, Tools for Textile Manufacture and Miscellaneous Bone, Terracotta and Stone Figurines, Pre-Persian Pottery, Attic Pottery, and Medieval Pottery edited by Andrea M. Berlin and Sharon C. Herbert KELSEY MUSEUM FIELDWORK SERIES ANN ARBOR, MI 2018 CONTENTS Preface . vii Summary of Occupation Sequence . .viii Site Plan with Trenches . ix 1 Wall Plaster and Stucco by Benton Kidd, with Catalogue Adapted from Robert L. Gordon, Jr. (1977) . .1 2 Personal Adornment: Glass, Stone, Bone, and Shell by Katherine A. Larson . .79 3 Glass Counters by Katherine A. Larson . .137 4 Tools for Textile Manufacture by Katherine A. Larson and Katherine M. Erdman . 145 Appendix: Catalogue of Miscellaneous Bone Objects by Katherine M. Erdman . 211 5 Terracotta and Stone Figurines by Adi Erlich . 217 6 Pottery of the Bronze and Iron Ages by William Dever and Ann Harrison . 261 7 The Attic Pottery by Ann Harrison and Andrea M. Berlin . 335 8 Medieval Ceramics by Adrian J. Boas . .359 PREFACE Tel Anafa II, iii comprises the last installment of final reports on the objects excavated at the site between 1968 and 1986 by the University of Missouri and the University of Michigan. -

W&L Traveller's

58-25 Queens Blvd., Woodside, NY 11357 T: (718) 280-5000; (800) 627-1244 F: (718) 204-4726 E: [email protected] W: www.classicescapes.com Nature & Cultural Journeys for the Discerning Traveler YOU ARE CORDIALLY INVITED TO JOIN THE W&L TRAVELLER’S ON A CULTURAL JOURNEY TO ISRAEL THE HERITAGE AND THE HOPE MARCH 16 TO 27, 2020 Schedules, accommodations and prices are accurate at the time of writing. They are subject to change. YOUR SPECIALIST-GUIDE: AMIR ORLY With more than 30 years experience, a Master’s degree in Biblical Studies and deep insight into his homeland’s complex past, Amir Orly is the ideal guide to show you Israel’s many treasures. He serves as a guide for dignitaries, media and heads of state and has developed and taught academic programs on religion and regional conflict for several American universities. Amir will enrich each stop along your journey with historical background and meaning. YOUR ITINERARY DAYS 1/2~MONDAY/TUESDAY~MARCH 16/17 WASHINGTON D.C./TEL AVIV/JERUSALEM Board your overnight flight to Israel. Upon arrival the next day, you will be greeted by your Classic Escapes guide, Amir Orly, and driven to your hotel in Jerusalem. En route, visit the Haas Promenade for stunning views of the entire Jerusalem landscape including the Old City and surrounding walls. Spend the next five days exploring Jerusalem, a mountainous city with a 5,000-year history, sacred to the three great monotheistic religions of the world – Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It is a major site of pilgrimage for all three religions as well as non-religious travelers, thanks to its unmatched historical and spiritual importance, its network of museums and concerts, and the archeological treasures that are continually discovered here. -

Archaeological Geophysics in Israel: Past, Present and Future

Adv. Geosci., 24, 45–68, 2010 www.adv-geosci.net/24/45/2010/ Advances in © Author(s) 2010. This work is distributed under Geosciences the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Archaeological geophysics in Israel: past, present and future L. V. Eppelbaum Dept. of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences, Raymond and Beverly Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv 69978, Tel Aviv, Israel Received: 4 February 2010 – Revised: 1 March 2010 – Accepted: 11 March 2010 – Published: 9 April 2010 Abstract. In Israel occur a giant number of archaeologi- 1 Introduction cal objects of various age, origin and size. Different kinds of noise complicate geophysical methods employment at ar- The territory of Israel, in spite of its comparatively small chaeological sites. Geodynamical active, multi-layered, and dimensions (about of 22 000 km2), contains extremely large geologically variable surrounding media in many cases dam- number of archaeological remains due to its rich ancient and ages ancient objects and disturbs their physical properties. Biblical history (map with location of several archaeological This calls to application of different geophysical methods sites displayed in this article, is presented in Fig. 1). Many armed by the modern interpretation technology. The main authors (e.g., Kenyon, 1979; Kempinski and Reich, 1992; attention is focused on the geophysical methods most fre- Meyers, 1996) note that the density location of archaeologi- quently applying in Israeli archaeological sites: GPR and cal sites on Israeli territory is the highest in the world. Geo- high-precise magnetic survey. Other methods (paleomag- physical methods are applied for the revealing and localiza- netic, resistivity, near-surface seismics, piezoelectric, etc.) tion of archaeological remains as rapid, effective and non- are briefly described and reviewed.