Associational Life in African Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Ufahamu: a Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title The State in African Historiography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sr988jq Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 4(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Thornton, John Publication Date 1973 DOI 10.5070/F742016445 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California - 113 - TIE STATE IN llfRI ~ HISTORI ffiRfffit': A REASSEssterr by JOHN THORNTON A great transformation has been wrought in African historiography as a by-product of the independence of Africa, and the increasing awareness of their African heritage by New World blacks. African historiography has ceased to be the crowing of imperialist historians or the subtle backing of a racist philosophy. Each year new research is turned out demonstrating time and again that Africans had a pre-colonial history, and that even during colonial times they played an important part in their own history. However, since African history has emerged as a field attracting the serious atten tion of historians, it must face the problems that confront all historiography; all the more since it has more than the ordinary impact on the people it purports to study. Because it is so closely involved in the political and social move ments of the present-day world, it demands of all engaged in writing African history - from the researcher down to the popular writer - that they show awareness of the problems of Africa and the Third World. African historiography, not surprisingly, bears the im print of its history, and its involvement in the polemics of Black Liberation and racism. -

The Afro-Portuguese Maritime World and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations THE AFRO-PORTUGUESE MARITIME WORLD AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF SPANISH CARIBBEAN SOCIETY, 1570-1640 By David Wheat Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2009 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Jane G. Landers Marshall C. Eakin Daniel H. Usner, Jr. David J. Wasserstein William R. Fowler Copyright © 2009 by John David Wheat All Rights Reserved For Sheila iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been completed without support from a variety of institutions over the past eight years. As a graduate student assistant for the preservation project “Ecclesiastical Sources for Slave Societies,” I traveled to Cuba twice, in Summer 2004 and in Spring 2005. In addition to digitizing late-sixteenth-century sacramental records housed in the Cathedral of Havana during these trips, I was fortunate to visit the Archivo Nacional de Cuba. The bulk of my dissertation research was conducted in Seville, Spain, primarily in the Archivo General de Indias, over a period of twenty months in 2005 and 2006. This extended research stay was made possible by three generous sources of funding: a Summer Research Award from Vanderbilt’s College of Arts and Sciences in 2005, a Fulbright-IIE fellowship for the academic year 2005-2006, and the Conference on Latin American History’s Lydia Cabrera Award for Cuban Historical Studies in Fall 2006. Vanderbilt’s Department of History contributed to my research in Seville by allowing me one semester of service-free funding. -

Table of Contents

José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course KIZOMBA TEACHERS1 COURSE José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course Syllabus « José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology » teachers course by José Garcia N’dongala. Copyright © First edition, January 2012 by José Garcia N’dongala President Zouk Style vzw/asbl (Kizombalove Academy) KIZOMBA TEACHERS COURSE 2 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course “Vision without action is a daydream. Action without vision is a nightmare” Japanese proverb “Do not dance because you feel like it. Dance because the music wants you to dance” Kizombalove proverb Kizombalove, where sensuality comes from… 3 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course All rights reserved. No part of this syllabus may be stored or reproduced in any way, electronically, mechanically or otherwise without prior written permission from the Author. 4 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 9 2 DANCE AND MUSIC ................................................................................................. 12 2.1 DANCING A HUMAN PHENOMENON ......................................................................... -

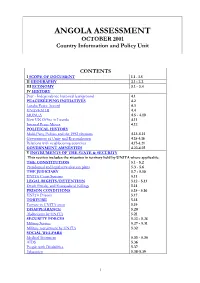

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 III ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.4 IV HISTORY Post - Independence historical background 4.1 PEACEKEEPING INITIATIVES 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.3 UNAVEM III 4.4 MONUA 4.5 - 4.10 New UN Office in Luanda 4.11 Internal Peace Moves 4.12 POLITICAL HISTORY Multi-Party Politics and the 1992 elections 4.13-4.14 Government of Unity and Reconciliation 4.15-4.16 Relations with neighbouring countries 4.17-4.21 GOVERNMENT AMNESTIES 4.22-4.25 V INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE & SECURITY This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. THE CONSTITUTION 5.1 - 5.2 Presidential and legislative election plans 5.3 - 5.6 THE JUDICIARY 5.7 - 5.10 UNITA Court Systems 5.11 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.12 - 5.13 Death Penalty and Extrajudicial Killings 5.14 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.15 - 5.16 UNITA Prisons 5.17 TORTURE 5.18 Torture in UNITA areas 5.19 DISAPPEARANCE 5.20 Abductions by UNITA 5.21 SECURITY FORCES 5.22 - 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.31 Military recruitment by UNITA 5.32 SOCIAL WELFARE Medical Treatment 5.33 - 5.35 AIDS 5.36 People with Disabilities 5.37 Education 5.38-5.39 1 VI HUMAN RIGHTS- GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SITUATION Introduction 6.1 SECURITY SITUATION Recent developments in the Civil War 6.2 - 6.17 Security situation in Luanda 6.18 - 6.19 Landmines 6.20 - 6.22 Human Rights monitoring 6.23 - 6.26 VII SPECIFIC GROUPS REFUGEES 7.1 Internally Displaced Persons & Humanitarian Situation 7.2-7.5 UNITA 7.6-7.8 Recent Political History of UNITA 7.9-7.12 UNITA-R 7.13-7.14 UNITA Military Wing 7.15-7.20 Surrendering UNITA Fighters 7.21 Sanctions against UNITA 7.22-7.25 F.L.E.C/CABINDANS 7.26 History of FLEC 7.27-7.28 Recent FLEC activity 7.29-7.34 The future of Cabindan separatists 7.35 ETHNIC GROUPS 7.36-7.37 Bakongo 7.38-7.46 WOMEN 7.47 Discrimination against women 7.48-7.59 CHILDREN 7.50-7.55 VIII RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. -

Angola Country Report

ANGOLA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Angola October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the document 1.1 2. Geography 2.1 3. Economy 3.1 4. History Post-Independence background since 1975 4.1 Multi-party politics and the 1992 Elections 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.6 Political Situation and Developments in the Civil War September 1999 - February 4.13 2002 End of the Civil War and Political Situation since February 2002 4.19 5. State Structures The Constitution 5.1 Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 Political System 5.9 Presidential and Legislative Election Plans 5.14 Judiciary 5.19 Court Structure 5.20 Traditional Courts 5.23 UNITA - Operated Courts 5.24 The Effect of the Civil War on the Judiciary 5.25 Corruption in the Judicial System 5.28 Legal Documents 5.30 Legal Rights/Detention 5.31 Death Penalty 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 Angolan National Police (ANP) 5.40 Armed Forces of Angola (Forças Armadas de Angola, FAA) 5.43 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.45 Military Service 5.49 Forced Conscription 5.52 Draft Evasion and Desertion 5.54 Child Soldiers 5.56 Medical Services 5.59 HIV/AIDS 5.67 Angola October 2004 People with Disabilities 5.72 Mental Health Treatment 5.81 Educational System 5.82 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues General 6.1 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.5 Newspapers 6.10 Radio and Television 6.13 Journalists 6.18 Freedom of Religion 6.25 Religious Groups 6.28 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.29 Political Activists – UNITA 6.43 -

Modern Ethnicity in Angola

Escola de Sociologia e Políticas Públicas The plateau of trials: modern ethnicity in Angola Vasco Martins Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Estudos Africanos Orientador: Fernando José Pereira Florêncio Doutor em Estudos Africanos, Professor Auxiliar, Departamento de Ciências da Vida, Universidade de Coimbra Agosto, 2015 Escola de Sociologia e Políticas Públicas The plateau of trials: modern ethnicity in Angola Vasco Martins Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Estudos Africanos Júri: Doutora Helena Maria Barroso Carvalho, Professora Auxiliar do ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Doutor José Carlos Gaspar Venâncio, Professor Catedrático do Departamento de Sociologia da Universidade da Beira Interior Doutor Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, Professor Auxiliar do St. Peters College da Universidade de Oxford Doutor Manuel António de Medeiros Ennes Ferreira, Professor Auxiliar do Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão Doutor Eduardo Costa Dias Martins, Professor Auxiliar do ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Doutora Ana Lúcia Lopes de Sá, Professora Auxiliar Convidada do ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Doutor Fernando José Pereira Florêncio, Professor Auxiliar da Faculdade de Ciência e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra (Orientador) Agosto, 2015 Acknowledgements The profession of an academic is many times regarded as solitary work. There is some truth to this statement, especially if like me, one spends most of the time reading, writing and agonising over countless editions at home. However, there is an uncountable amount of people involved in bringing a PhD thesis to life, people to whom I am most grateful. During the duration of my PhD programme I have benefitted from a scholarship provided by the FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. -

MINISTRY of PLANNING Public Disclosure Authorized

E1835 REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA v2 MINISTRY OF PLANNING Public Disclosure Authorized EMERGENCY MULTISECTOR RECOVERY PROJECT (EMRP) PROJECT MANAGEMENT IMPLEMENTATION UNIT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Process Report Volume 2 – Environmental and Social Diagnosis and Institutional and Legal Framework INDEX Page 1 - INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................4 2 - THE EMERGENCY ENVIRONMENTAL MULTISECTOR PROJECT (EMRP) ................................................................................................................5 2.1 - EMRP’S OBJECTIVES ..........................................................................................5 2.2 - PHASING................................................................................................................5 2.3 - COMPONENTS OF THE IDA PROJECT .............................................................6 2.3.1 - Component A – Rural Development and Social Services Scheme .............6 2.3.1.1 - Sub-component A1: Agricultural and Rural Development..........6 2.3.1.2 - Sub-Component A2: Health.........................................................8 2.3.1.3 - Sub-Component A3: Education ...................................................9 2.3.2 - Component B – Reconstruction and Rehabilitation of critical Infrastructures ............................................................................................10 2.3.2.1 - Sub-Component -

Luanda City Profile Paul Jenkins, Paul Robson & Allan Cain

Luanda city profile Paul Jenkins, Paul Robson & Allan Cain Abstract Luanda, the capital city of Angola, faces extreme urban development challenges, due to the extremely turbulent history of the country, the city’s peripheral role in the global economy, and the resulting extremely high urban growth rates and widespread poverty. This profile reviews the historical and current political and economic basis for the city in three main periods, and the physical, demographic and socio-economic situation, as the background for understanding the successes and failures of urban development activities in recent years. It highlights the potential for scaling up pilot projects which engage the poor majority of urban dwellers pro-actively in urban development, with assistance from NGOs and international agencies, although indicates the need to create a firm political base for secure social and economic urban development. Contents Historical development ....................................................................................................... 1 Early history ....................................................................................................................... 1 The colonial period ............................................................................................................. 2 Post-Independence ............................................................................................................ 5 Urban characteristics ......................................................................................................... -

Angola's People

In the Eye of the Storm: Angola's People http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp20002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org In the Eye of the Storm: Angola's People Author/Creator Davidson, Basil Publisher Anchor Books Anchor Press/Doubleday Date 1973-00-00 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, Zambia, Congo, the Democratic Republic of the, Congo Coverage (temporal) 1600 - 1972 Rights By kind permission of Basil R. Davidson. Description This book provides both historical background and a description of Davidson's trip to eastern Angola with MPLA guerrilla forces. -

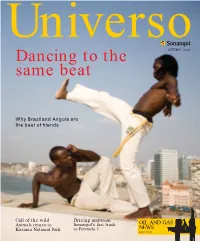

Dancing to the Same Beat

SU_19:Layout 1 1/9/08 10:22 Page 1 Universo Dancing to the AUTUMN 2008 same beat Why Brazil and Angola are the best of friends Call of the wild Driving ambition Animals return to Sonangol’s fast track OIL AND GAS Kissama National Park to Formula 1 NEWS pages 38-51 SU_19:Layout 1 1/9/08 10:23 Page 2 THE BIG PICTURE CONTENTS Name: Kikongo LANGUAGES Not forgotten: elephants in AKA: Quicongo, Congo, Kongo Kissama park, p24 Cabinda Spoken by: Bakongo Sonangol Department for Cabinda Number of speakers: 1m Communication & Image Name: Kimbundu Useful phrase: “How are you?” Director Mbanza translates as “Unam m’bote?” AKA: Quimbundo Soyo Congo Spoken by: Ambundu João Rosa Santos Numbers of speakers: 2m Zaire Corporate Communications Word fact: The name Angola Uíge Assistants comes from the Kimbundu ngola, Cristina de Novaes, meaning king Dundo Raimundo Vilares Uíge Bengo Caxito Lucapa Name: Umbundu Publisher Luanda Malanje AKA: Umbundo Sheila O’Callaghan Luanda Kwanza Norte Lunda Norte Spoken by: Ovimbundo Number of speakers: 4m Editor Ndalatando Alex Bellos Malanje Useful phrase: “What's Saurimo this?” translates as “Eci nye?” Art Director David Gould Lunda Sul Calulo Sub Editor Kwanza Sul Ron Gribble Sumbe Advertising Design Bernd Wojtczack Bié Luena Lobito Huambo Circulation Manager Benguela Kuito Matthew Alexander Huambo Group President Benguela John Charles Gasser Moxico Name: Tchokwé Project Consultant AKA: Ciokwe, Cokwe, Shioko, Nathalie MacCarthy Quioco, Djok, Tschiokloe istockphoto.com/David T Gomez Huíla Spoken by: Lunda-Tchokwé This magazine is produced for Menongue Number of speakers: Sonangol by Impact Media Letter from the editor 4 Lubango 850,000 Custom Publishing. -

Angola Country Report BTI 2012

BTI 2012 | Angola Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.92 # 83 of 128 Political Transformation 1-10 4.88 # 78 of 128 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.96 # 82 of 128 Management Index 1-10 4.18 # 91 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2012. The BTI is a global assessment of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economy as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — Angola Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. © 2012 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2012 | Angola 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 19.1 HDI 0.486 GDP p.c. $ 6120 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.8 HDI rank of 187 148 Gini Index 58.6 Life expectancy years 50 UN Education Index 0.422 Poverty3 % 70.2 Urban population % 58.5 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 12.9 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2011. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Although transformation in Angola has progressed since the end of civil war in 2002, developments during the review period (2009 – 2010) cast doubt on the regime’s commitment to democracy. The government does target market economic development, but there is ongoing internal resistance to this orientation, which frustrates the consistent implementation of policies that could further this. -

The New York African Burial Ground

THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND HISTORY FINAL REPORT Edited by Edna Greene Medford, Ph. D. THE AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND PROJECT HOWARD UNIVERSITY WASHINGTON, DC FOR THE UNITED STATES GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NORTHEAST AND CARIBBEAN REGION November 2004 Howard University’s New York African Burial Ground Project was funded by the U.S. General Services Administration under Contract No. GS-02P-93-CUC-0071 ╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬╬ Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. General Services Administration or Howard University. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Maps vi List of Tables vii List of Figures viii List of Contributors ix Acknowledgements xi Introduction xiii Purpose and Goals Methodology Distribution of Tasks An Overview Part One: Origins and Arrivals 1.0 The African Burial Ground: New York’s First Black Institution 2 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Burial in the Common 2.0 The Quest for Labor--From Privateering to “Honest” Trade 9 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Native Inhabitants 2.3 From Trading Post to Settlement 2.4 African Arrival 3.0 West Central African Origins of New Amsterdam’s Black Population 17 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Political Structures 3.3 The Acquisition of Central African Laborers in the Seventeenth Century iii 4.0 Slavery and Freedom in New Amsterdam 25 4.1 Introduction 4.2 The Meaning of Slavery during the Dutch Period 4.3 The Employment of Enslaved Labor in New Amsterdam 4.4 Social Foundations