UCLA Ufahamu: a Journal of African Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development at the Border: a Study of National Integration in Post-Colonial West Africa

Development at the border : a study of national integration in post-colonial West Africa Denis Cogneau, Sandrine Mesplé-Somps, Gilles Spielvogel To cite this version: Denis Cogneau, Sandrine Mesplé-Somps, Gilles Spielvogel. Development at the border : a study of national integration in post-colonial West Africa. 2010. halshs-00966312 HAL Id: halshs-00966312 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00966312 Preprint submitted on 26 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Development at the border: a study of national integration in post-colonial West Africa Denis COGNEAU Sandrine MESPLE-SOMPS Gilles SPIELVOGEL Paris School of Economics IRD DIAL Univ. Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne September 2010 G-MonD Working Paper n°15 For sustainable and inclusive world development Development at the border: a study of national integration in post-colonial West Africa¤ Denis Cogneau,y Sandrine Mespl¶e-Somps,z and Gilles Spielvogelx September 20, 2010 Abstract In Africa, boundaries delineated during the colonial era now divide young in- dependent states. By applying regression discontinuity designs to a large set of surveys covering the 1986-2001 period, this paper identi¯es many large and signif- icant jumps in welfare at the borders between ¯ve West-African countries around Cote d'Ivoire. -

Guinea's 2008 Military Coup and Relations with the United States

Guinea's 2008 Military Coup and Relations with the United States Alexis Arieff Analyst in African Affairs Nicolas Cook Specialist in African Affairs July 16, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40703 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Guinea's 2008 Military Coup and Relations with the United States Summary Guinea is a Francophone West African country on the Atlantic coast, with a population of about 10 million. It is rich in natural resources but characterized by widespread poverty and limited socio-economic growth and development. While Guinea has experienced regular episodes of internal political turmoil, it was considered a locus of relative stability over the past two decades, a period during which each of its six neighbors suffered one or more armed internal conflicts. Guinea entered a new period of political uncertainty on December 23, 2008, when a group of junior and mid-level military officers seized power, hours after the death of longtime president and former military leader Lansana Conté. Calling itself the National Council for Democracy and Development (CNDD, after its French acronym), the junta named as interim national president Captain Moussa Dadis Camara, previously a relatively unknown figure. The junta appointed a civilian prime minister and has promised to hold presidential and legislative elections by late 2009. However, some observers fear that rivalries within the CNDD, Dadis Camara's lack of national leadership experience, and administrative and logistical challenges could indefinitely delay the transfer of power to a democratically elected civilian administration. Guinea has never undergone a democratic or constitutional transfer of power since gaining independence in 1958, and Dadis Camara is one of only three persons to occupy the presidency since that time. -

The Afro-Portuguese Maritime World and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations THE AFRO-PORTUGUESE MARITIME WORLD AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF SPANISH CARIBBEAN SOCIETY, 1570-1640 By David Wheat Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2009 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Jane G. Landers Marshall C. Eakin Daniel H. Usner, Jr. David J. Wasserstein William R. Fowler Copyright © 2009 by John David Wheat All Rights Reserved For Sheila iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been completed without support from a variety of institutions over the past eight years. As a graduate student assistant for the preservation project “Ecclesiastical Sources for Slave Societies,” I traveled to Cuba twice, in Summer 2004 and in Spring 2005. In addition to digitizing late-sixteenth-century sacramental records housed in the Cathedral of Havana during these trips, I was fortunate to visit the Archivo Nacional de Cuba. The bulk of my dissertation research was conducted in Seville, Spain, primarily in the Archivo General de Indias, over a period of twenty months in 2005 and 2006. This extended research stay was made possible by three generous sources of funding: a Summer Research Award from Vanderbilt’s College of Arts and Sciences in 2005, a Fulbright-IIE fellowship for the academic year 2005-2006, and the Conference on Latin American History’s Lydia Cabrera Award for Cuban Historical Studies in Fall 2006. Vanderbilt’s Department of History contributed to my research in Seville by allowing me one semester of service-free funding. -

Table of Contents

José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course KIZOMBA TEACHERS1 COURSE José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course Syllabus « José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology » teachers course by José Garcia N’dongala. Copyright © First edition, January 2012 by José Garcia N’dongala President Zouk Style vzw/asbl (Kizombalove Academy) KIZOMBA TEACHERS COURSE 2 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course “Vision without action is a daydream. Action without vision is a nightmare” Japanese proverb “Do not dance because you feel like it. Dance because the music wants you to dance” Kizombalove proverb Kizombalove, where sensuality comes from… 3 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course All rights reserved. No part of this syllabus may be stored or reproduced in any way, electronically, mechanically or otherwise without prior written permission from the Author. 4 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 9 2 DANCE AND MUSIC ................................................................................................. 12 2.1 DANCING A HUMAN PHENOMENON ......................................................................... -

AHMED SEKOU TOURE, a RADICAL HERO the New York Times

5/31/2016 AHMED SEKOU TOURE, A RADICAL HERO The New York Times This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, please click here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. » March 28, 1984 AHMED SEKOU TOURE, A RADICAL HERO By ERIC PACE To Ahmed Sekou Toure, the President of Guinea, who died Monday in a Cleveland hospital, it was better for his western African country to live in poverty than to accept what he denounced as ''riches in slavery'' as part of the French Community. The President, a towering charismatic and radical figure in Africa's postcolonial history, led his country to independence from France in 1958 and ruled it with a strong hand for 26 years. The 62yearold leader was black Africa's longest serving head of state. He presided over one of the world's poorest nations. The Guinea radio said the President died of an apparent heart attack. He had gone to the Cleveland Clinic Monday for emergency heart treatment, and a spokesman there said yesterday that the President had succumbed during heart surgery. Organizing a referendum in 1958 that rejected close ties with France, Mr. Toure said, ''Guinea prefers poverty in freedom to riches in slavery.'' After rejecting French ties, Mr. Toure made his country into a closed Soviet client state, and his Democratic Party of Guinea into its only political organization. -

Associational Life in African Cities

ASSOCIATIONAL LIFE IN AFRICAN CITIES Popular Responses to the Urban Crisis Edited by Arne Tostensen – Inge Tvedten – Mariken Vaa Nordiska Afrikainstitutet 2001 CHAPTER 15 Communities and Community Institutions in Luanda, Angola Paul Robson BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY This paper is based on research carried out in December 1996 in urban areas in Angola, as part of a larger study of communities and community institu- tions in the country. The research examined community institutions as a po- tential basis for development interventions in urban areas, mainly in the capi- tal city Luanda. The research was a response to the severe lack of information about people’s living conditions, institutions and production systems in An- gola. The research project was carried out through semi-structured interviews with key informants in Government and in Non-Governmental Organisations. Case-studies in two peri-urban bairros (spontaneous, unserviced settlements) were carried out through semi-structured interviews and through focus-group discussions. The interviews and discussion groups focused on the growth and structure of Luanda, coping strategies, family and neighbourhood co- operation, community structures, relations with Government and views on development. Other previous studies were also re-analysed (Amado, Cruz and Hakkert, 1992; INE, 1993). The two bairros which were studied in depth were Palanca and Hoji-ya- Henda. The bairro Palanca is inhabited by people from the north of Angola of the Bakongo group, many of whom lived in exile in Kinshasa from about 1961 to 1982. The bairro Hoji-ya-Henda is inhabited mainly by people from the immediate Luanda hinterland and from the Kimbundu group. -

BY the TIME YOU READ THIS, WE'll ALL BE DEAD: the Failures of History and Institutions Regarding the 2013-2015 West African Eb

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. George Denkey Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Denkey, George, "BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic.". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/517 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. By Georges Kankou Denkey A Thesis Submitted to the Department Of Urban Studies of Trinity College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts Degree 1 Table Of Contents For Ameyo ………………………………………………..………………………........ 3 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… 6 Ebola: A Background …………………………………………………………………… 20 The Past is a foreign country: Historical variables behind the spread ……………… 39 Ebola: The Detailed Trajectory ………………………………………………………… 61 Why it spread: Cultural -

Domination and Resistance Through the Prism of Postage Stamps

Afrika Zamani, No. 17, 2009, pp. 227-246 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa & Association of African Historians 2012 (ISSN 0850-3079) Domination and Resistance through the Prism of Postage Stamps Agbenyega Adedze* Abstract Every country issues postage stamps. Stamps were originally construed as pre- payment for the service of transporting letters and packages. However, images on stamps have become mediums for the transmission of propagandist messages about the country of issue to its citizens and the rest of the world. Commemorative postage stamps venerate special events, occasions or personalities and are, therefore, subject to political and social pressure from special interest groups. It is not, therefore, surprising that during the colonial era, Europeans memorialized conquerors and explorers on postage stamps and, likewise after independence, African countries have commemorated some of their leaders (freedom fighters, martyrs, politicians, chiefs, etc.) who resisted colonial rule. Using postage stamps of British and French colonies and six independent countries (Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria and Senegal) in West Africa, I will try to explain why certain individuals are honored and why others are not. I argue that since the issuing of postage stamps remains the monopoly of the central government, these commemorative stamps about domination and resistance are subjective and are found to be interpreted through contemporary political prism. Recent democratic dispensation in Africa has also influenced commemorative stamps to a large extent. Under these conditions, public history debates are now possible where people could claim their own history, and I predict that as more constituents realize the value of postage stamps, marginalized groups will demand stamps for their heroes and heroines. -

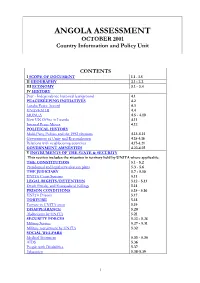

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 III ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.4 IV HISTORY Post - Independence historical background 4.1 PEACEKEEPING INITIATIVES 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.3 UNAVEM III 4.4 MONUA 4.5 - 4.10 New UN Office in Luanda 4.11 Internal Peace Moves 4.12 POLITICAL HISTORY Multi-Party Politics and the 1992 elections 4.13-4.14 Government of Unity and Reconciliation 4.15-4.16 Relations with neighbouring countries 4.17-4.21 GOVERNMENT AMNESTIES 4.22-4.25 V INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE & SECURITY This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. THE CONSTITUTION 5.1 - 5.2 Presidential and legislative election plans 5.3 - 5.6 THE JUDICIARY 5.7 - 5.10 UNITA Court Systems 5.11 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.12 - 5.13 Death Penalty and Extrajudicial Killings 5.14 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.15 - 5.16 UNITA Prisons 5.17 TORTURE 5.18 Torture in UNITA areas 5.19 DISAPPEARANCE 5.20 Abductions by UNITA 5.21 SECURITY FORCES 5.22 - 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.31 Military recruitment by UNITA 5.32 SOCIAL WELFARE Medical Treatment 5.33 - 5.35 AIDS 5.36 People with Disabilities 5.37 Education 5.38-5.39 1 VI HUMAN RIGHTS- GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SITUATION Introduction 6.1 SECURITY SITUATION Recent developments in the Civil War 6.2 - 6.17 Security situation in Luanda 6.18 - 6.19 Landmines 6.20 - 6.22 Human Rights monitoring 6.23 - 6.26 VII SPECIFIC GROUPS REFUGEES 7.1 Internally Displaced Persons & Humanitarian Situation 7.2-7.5 UNITA 7.6-7.8 Recent Political History of UNITA 7.9-7.12 UNITA-R 7.13-7.14 UNITA Military Wing 7.15-7.20 Surrendering UNITA Fighters 7.21 Sanctions against UNITA 7.22-7.25 F.L.E.C/CABINDANS 7.26 History of FLEC 7.27-7.28 Recent FLEC activity 7.29-7.34 The future of Cabindan separatists 7.35 ETHNIC GROUPS 7.36-7.37 Bakongo 7.38-7.46 WOMEN 7.47 Discrimination against women 7.48-7.59 CHILDREN 7.50-7.55 VIII RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. -

Angola Country Report

ANGOLA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Angola October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the document 1.1 2. Geography 2.1 3. Economy 3.1 4. History Post-Independence background since 1975 4.1 Multi-party politics and the 1992 Elections 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.6 Political Situation and Developments in the Civil War September 1999 - February 4.13 2002 End of the Civil War and Political Situation since February 2002 4.19 5. State Structures The Constitution 5.1 Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 Political System 5.9 Presidential and Legislative Election Plans 5.14 Judiciary 5.19 Court Structure 5.20 Traditional Courts 5.23 UNITA - Operated Courts 5.24 The Effect of the Civil War on the Judiciary 5.25 Corruption in the Judicial System 5.28 Legal Documents 5.30 Legal Rights/Detention 5.31 Death Penalty 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 Angolan National Police (ANP) 5.40 Armed Forces of Angola (Forças Armadas de Angola, FAA) 5.43 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.45 Military Service 5.49 Forced Conscription 5.52 Draft Evasion and Desertion 5.54 Child Soldiers 5.56 Medical Services 5.59 HIV/AIDS 5.67 Angola October 2004 People with Disabilities 5.72 Mental Health Treatment 5.81 Educational System 5.82 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues General 6.1 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.5 Newspapers 6.10 Radio and Television 6.13 Journalists 6.18 Freedom of Religion 6.25 Religious Groups 6.28 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.29 Political Activists – UNITA 6.43 -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

History Textbook West African Senior School Certificate Examination

History Textbook West African Senior School Certificate Examination This textbook is a free resource which be downloaded here: https://wasscehistorytextbook.com/ Please use the following licence if you want to reuse the content of this book: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0). It means that you can share (copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format) and adapt its content (remix, transform, and build upon the material). Under the following terms, you must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. If you want to cite the textbook: Achebe, Nwando, Samuel Adu-Gyamfi, Joe Alie, Hassoum Ceesay, Toby Green, Vincent Hiribarren, Ben Kye-Ampadu, History Textbook: West African Senior School Certificate Examination (2018), https://wasscehistorytextbook.com/ ISBN issued by the National Library of Gambia: 978-9983-960-20-4 Cover illustration: Students at Aberdeen Primary School on June 22, 2015 in Freetown Sierra Leone. Photo © Dominic Chavez/World Bank, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/wtYAdS 1 Contents Why this ebook? ................................................................................. 3 Funders ............................................................................................... 4 Authors ..............................................................................................