Luanda City Profile Paul Jenkins, Paul Robson & Allan Cain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Ufahamu: a Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title The State in African Historiography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sr988jq Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 4(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Thornton, John Publication Date 1973 DOI 10.5070/F742016445 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California - 113 - TIE STATE IN llfRI ~ HISTORI ffiRfffit': A REASSEssterr by JOHN THORNTON A great transformation has been wrought in African historiography as a by-product of the independence of Africa, and the increasing awareness of their African heritage by New World blacks. African historiography has ceased to be the crowing of imperialist historians or the subtle backing of a racist philosophy. Each year new research is turned out demonstrating time and again that Africans had a pre-colonial history, and that even during colonial times they played an important part in their own history. However, since African history has emerged as a field attracting the serious atten tion of historians, it must face the problems that confront all historiography; all the more since it has more than the ordinary impact on the people it purports to study. Because it is so closely involved in the political and social move ments of the present-day world, it demands of all engaged in writing African history - from the researcher down to the popular writer - that they show awareness of the problems of Africa and the Third World. African historiography, not surprisingly, bears the im print of its history, and its involvement in the polemics of Black Liberation and racism. -

Ongoing Dengue Epidemic — Angola, June 2013

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Early Release / Vol. 62 June 17, 2013 Ongoing Dengue Epidemic — Angola, June 2013 On April 1, 2013, the Public Health Directorate of Angola many international business travelers, primarily because of announced that six cases of dengue had been reported to commerce in oil. the Ministry of Health of Angola (MHA). As of May 31, a Weak centralized surveillance for illnesses of public health total of 517 suspected dengue cases had been reported and importance has made it difficult for MHA to focus resources tested for dengue with a rapid diagnostic test (RDT). A on populations in need. Although malaria is the greatest total of 313 (60.5%) specimens tested positive for dengue, cause of morbidity and mortality in Angola (1), incidence including one from a patient who died. All suspected cases is comparatively low in Luanda (2); however, an increase in were reported from Luanda Province, except for two from malaria cases was detected in Luanda in 2012. Dengue was Malanje Province. Confirmatory diagnostic testing of 49 reported in travelers recently returned from Angola in 1986 specimens (43 RDT-positive and six RDT-negative) at the and during 1999–2002 (3). Surveys conducted by the National CDC Dengue Branch confirmed dengue virus (DENV) Malaria Control Program during 2010–2012 showed that infection in 100% of the RDT-positive specimens and 50% of Aedes aegypti is the only DENV vector in Angola, and is present the RDT-negative specimens. Only DENV-1 was detected by in all 18 provinces except Moxico. molecular diagnostic testing. Phylogenetic analysis indicated this virus has been circulating in the region since at least 1968, Epidemiologic and Laboratory Investigation strongly suggesting that dengue is endemic in Angola. -

Angolan Vegetable Crops Have Unique Genotypes of Potential Value For

Research Article Unique vegetable germplasm in Angola Page 1 of 12 Angolan vegetable crops have unique genotypes of AUTHORS: potential value for future breeding programmes José P. Domingos1 Ana M. Fita2 María B. Picó2 A survey was carried out in Angola with the aim of collecting vegetable crops. Collecting expeditions were Alicia Sifres2 conducted in Kwanza-Sul, Benguela, Huíla and Namibe Provinces and a total of 80 accessions belonging Isabel H. Daniel3 to 22 species was collected from farmers and local markets. Species belonging to the Solanaceae Joana Salvador3 (37 accessions) and Cucurbitaceae (36 accessions) families were the most frequently found with pepper and Jose Pedro3 eggplant being the predominant solanaceous crops collected. Peppers were sold in local markets as a mixture Florentino Sapalo3 of different types, even different species: Capsicum chinense, C. baccatum, C. frutescens and C. pubescens. Pedro Mozambique3 Most of the eggplant accessions collected belonged to Solanum aethiopicum L. Gilo Group, the so-called María J. Díez2 ‘scarlet eggplant’. Cucurbita genus was better represented than the other cucurbit crops. A high morphological variation was present in the Cucurbita maxima and C. moschata accessions. A set of 22 Cucurbita accessions AFFILIATIONS: 1Department of Biology, from Angola, along with 32 Cucurbita controls from a wide range of origins, was cultivated in Valencia, Spain Science Faculty, University and characterised based on morphology and molecularity using a set of 15 microsatellite markers. A strong Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola dependence on latitude was found in most of the accessions and as a result, many accessions did not set 2Institute for the Conservation fruit. -

Chapter 15 the Mammals of Angola

Chapter 15 The Mammals of Angola Pedro Beja, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Luís Veríssimo, Elena Bersacola, Ezequiel Fabiano, Jorge M. Palmeirim, Ara Monadjem, Pedro Monterroso, Magdalena S. Svensson, and Peter John Taylor Abstract Scientific investigations on the mammals of Angola started over 150 years ago, but information remains scarce and scattered, with only one recent published account. Here we provide a synthesis of the mammals of Angola based on a thorough survey of primary and grey literature, as well as recent unpublished records. We present a short history of mammal research, and provide brief information on each species known to occur in the country. Particular attention is given to endemic and near endemic species. We also provide a zoogeographic outline and information on the conservation of Angolan mammals. We found confirmed records for 291 native species, most of which from the orders Rodentia (85), Chiroptera (73), Carnivora (39), and Cetartiodactyla (33). There is a large number of endemic and near endemic species, most of which are rodents or bats. The large diversity of species is favoured by the wide P. Beja (*) CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal CEABN-InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] L. Veríssimo Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola e-mail: [email protected] E. -

The Afro-Portuguese Maritime World and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations THE AFRO-PORTUGUESE MARITIME WORLD AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF SPANISH CARIBBEAN SOCIETY, 1570-1640 By David Wheat Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2009 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Jane G. Landers Marshall C. Eakin Daniel H. Usner, Jr. David J. Wasserstein William R. Fowler Copyright © 2009 by John David Wheat All Rights Reserved For Sheila iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been completed without support from a variety of institutions over the past eight years. As a graduate student assistant for the preservation project “Ecclesiastical Sources for Slave Societies,” I traveled to Cuba twice, in Summer 2004 and in Spring 2005. In addition to digitizing late-sixteenth-century sacramental records housed in the Cathedral of Havana during these trips, I was fortunate to visit the Archivo Nacional de Cuba. The bulk of my dissertation research was conducted in Seville, Spain, primarily in the Archivo General de Indias, over a period of twenty months in 2005 and 2006. This extended research stay was made possible by three generous sources of funding: a Summer Research Award from Vanderbilt’s College of Arts and Sciences in 2005, a Fulbright-IIE fellowship for the academic year 2005-2006, and the Conference on Latin American History’s Lydia Cabrera Award for Cuban Historical Studies in Fall 2006. Vanderbilt’s Department of History contributed to my research in Seville by allowing me one semester of service-free funding. -

Table of Contents

José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course KIZOMBA TEACHERS1 COURSE José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course Syllabus « José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology » teachers course by José Garcia N’dongala. Copyright © First edition, January 2012 by José Garcia N’dongala President Zouk Style vzw/asbl (Kizombalove Academy) KIZOMBA TEACHERS COURSE 2 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course “Vision without action is a daydream. Action without vision is a nightmare” Japanese proverb “Do not dance because you feel like it. Dance because the music wants you to dance” Kizombalove proverb Kizombalove, where sensuality comes from… 3 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course All rights reserved. No part of this syllabus may be stored or reproduced in any way, electronically, mechanically or otherwise without prior written permission from the Author. 4 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 9 2 DANCE AND MUSIC ................................................................................................. 12 2.1 DANCING A HUMAN PHENOMENON ......................................................................... -

Associational Life in African Cities

ASSOCIATIONAL LIFE IN AFRICAN CITIES Popular Responses to the Urban Crisis Edited by Arne Tostensen – Inge Tvedten – Mariken Vaa Nordiska Afrikainstitutet 2001 CHAPTER 15 Communities and Community Institutions in Luanda, Angola Paul Robson BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY This paper is based on research carried out in December 1996 in urban areas in Angola, as part of a larger study of communities and community institu- tions in the country. The research examined community institutions as a po- tential basis for development interventions in urban areas, mainly in the capi- tal city Luanda. The research was a response to the severe lack of information about people’s living conditions, institutions and production systems in An- gola. The research project was carried out through semi-structured interviews with key informants in Government and in Non-Governmental Organisations. Case-studies in two peri-urban bairros (spontaneous, unserviced settlements) were carried out through semi-structured interviews and through focus-group discussions. The interviews and discussion groups focused on the growth and structure of Luanda, coping strategies, family and neighbourhood co- operation, community structures, relations with Government and views on development. Other previous studies were also re-analysed (Amado, Cruz and Hakkert, 1992; INE, 1993). The two bairros which were studied in depth were Palanca and Hoji-ya- Henda. The bairro Palanca is inhabited by people from the north of Angola of the Bakongo group, many of whom lived in exile in Kinshasa from about 1961 to 1982. The bairro Hoji-ya-Henda is inhabited mainly by people from the immediate Luanda hinterland and from the Kimbundu group. -

Creating Markets in Angola : Country Private Sector Diagnostic

CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA MARKETS IN CREATING COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC SECTOR PRIVATE COUNTRY COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA Opportunities for Development Through the Private Sector COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA Opportunities for Development Through the Private Sector About IFC IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of the world. In fiscal year 2018, we delivered more than $23 billion in long-term financing for developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. For more information, visit www.ifc.org © International Finance Corporation 2019. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The findings, interpretations, views, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Finance Corporation or of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank) or the governments they represent. -

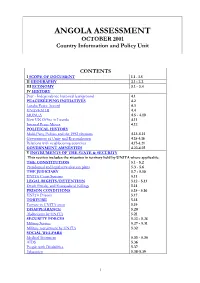

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 III ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.4 IV HISTORY Post - Independence historical background 4.1 PEACEKEEPING INITIATIVES 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.3 UNAVEM III 4.4 MONUA 4.5 - 4.10 New UN Office in Luanda 4.11 Internal Peace Moves 4.12 POLITICAL HISTORY Multi-Party Politics and the 1992 elections 4.13-4.14 Government of Unity and Reconciliation 4.15-4.16 Relations with neighbouring countries 4.17-4.21 GOVERNMENT AMNESTIES 4.22-4.25 V INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE & SECURITY This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. THE CONSTITUTION 5.1 - 5.2 Presidential and legislative election plans 5.3 - 5.6 THE JUDICIARY 5.7 - 5.10 UNITA Court Systems 5.11 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.12 - 5.13 Death Penalty and Extrajudicial Killings 5.14 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.15 - 5.16 UNITA Prisons 5.17 TORTURE 5.18 Torture in UNITA areas 5.19 DISAPPEARANCE 5.20 Abductions by UNITA 5.21 SECURITY FORCES 5.22 - 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.31 Military recruitment by UNITA 5.32 SOCIAL WELFARE Medical Treatment 5.33 - 5.35 AIDS 5.36 People with Disabilities 5.37 Education 5.38-5.39 1 VI HUMAN RIGHTS- GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SITUATION Introduction 6.1 SECURITY SITUATION Recent developments in the Civil War 6.2 - 6.17 Security situation in Luanda 6.18 - 6.19 Landmines 6.20 - 6.22 Human Rights monitoring 6.23 - 6.26 VII SPECIFIC GROUPS REFUGEES 7.1 Internally Displaced Persons & Humanitarian Situation 7.2-7.5 UNITA 7.6-7.8 Recent Political History of UNITA 7.9-7.12 UNITA-R 7.13-7.14 UNITA Military Wing 7.15-7.20 Surrendering UNITA Fighters 7.21 Sanctions against UNITA 7.22-7.25 F.L.E.C/CABINDANS 7.26 History of FLEC 7.27-7.28 Recent FLEC activity 7.29-7.34 The future of Cabindan separatists 7.35 ETHNIC GROUPS 7.36-7.37 Bakongo 7.38-7.46 WOMEN 7.47 Discrimination against women 7.48-7.59 CHILDREN 7.50-7.55 VIII RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. -

Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola

Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola By Aaron Laurence deGrassi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Professor Gillian P. Hart Professor Peter B. Evans Abstract Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola by Aaron Laurence deGrassi Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Fueled by a massive offshore deep-water oil boom, Angola has since the end of war in 2002 undertaken a huge, complex, and contradictory national reconstruction program whose character and dynamics have yet to be carefully studied and analyzed. What explains the patterns of such projects, who is benefitting from them, and how? The dissertation is grounded in the specific dynamics of cassava production, processing and marketing in two villages in Western Malanje Province in north central Angola. The ways in which Western Malanje’s cassava farmers’ livelihoods are shaped by transport, marketing, and an overall agrarian configuration illustrate how contemporary reconstruction – in the context of an offshore oil boom – has occurred through the specific conjunctures of multiple geo-historical processes associated with settler colonialism, protracted war, and leveraged liberalization. Such an explanation contrasts with previous more narrow emphases on elite enrichment and domination through control of external trade. Infrastructure projects are occurring as part of an agrarian configuration in which patterns of land, roads, and markets have emerged through recursive relations, and which is characterized by concentration, hierarchy and fragmentation. -

One Century of Angolan Diamonds

One century of Angolan diamonds A report authored and coordinated by Luís Chambel with major contributions by Luís Caetano and Manuel Reis Contacts For inquiries regarding this report, diamond or other mineral projects in Angola please contact: Luís Chambel Manuel Reis [email protected] [email protected] P: +351 217 594 018 P: +244 222 441 362 M: +351 918 369 047 F: +244 222 443 274 Sínese M: +244 923 382 924 R. Direita 27 – 1E M: +351 968 517 222 1600-435 LISBOA Eaglestone PORTUGAL R. Marechal Brós Tito 35/37 – 9B Kinaxixi Ingombota, LUANDA ANGOLA Media contacts: [email protected] or [email protected] Disclaimer This document has been prepared by Sínese – Consultoria Ld.ª and Eaglestone Advisory Limited and is provided for information purposes only. Eaglestone Advisory Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the United Kingdom and its affiliates (“Eaglestone”). The information and opinions in this document are published for the assistance of the recipients, are for information purposes only, and have been compiled by Sínese and Eaglestone in good faith using sources of public information considered reliable. Although all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the information contained herein is not untrue or misleading we make no representation regarding its accuracy or completeness, it should not be relied upon as authoritative or definitive, and should not be taken into account in the exercise of judgments by any recipient. Accordingly, with the exception of information about Sínese and Eaglestone, Sínese and Eaglestone make no representation as to the accuracy or completeness of such information. -

Angola Country Report

ANGOLA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Angola October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the document 1.1 2. Geography 2.1 3. Economy 3.1 4. History Post-Independence background since 1975 4.1 Multi-party politics and the 1992 Elections 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.6 Political Situation and Developments in the Civil War September 1999 - February 4.13 2002 End of the Civil War and Political Situation since February 2002 4.19 5. State Structures The Constitution 5.1 Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 Political System 5.9 Presidential and Legislative Election Plans 5.14 Judiciary 5.19 Court Structure 5.20 Traditional Courts 5.23 UNITA - Operated Courts 5.24 The Effect of the Civil War on the Judiciary 5.25 Corruption in the Judicial System 5.28 Legal Documents 5.30 Legal Rights/Detention 5.31 Death Penalty 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 Angolan National Police (ANP) 5.40 Armed Forces of Angola (Forças Armadas de Angola, FAA) 5.43 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.45 Military Service 5.49 Forced Conscription 5.52 Draft Evasion and Desertion 5.54 Child Soldiers 5.56 Medical Services 5.59 HIV/AIDS 5.67 Angola October 2004 People with Disabilities 5.72 Mental Health Treatment 5.81 Educational System 5.82 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues General 6.1 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.5 Newspapers 6.10 Radio and Television 6.13 Journalists 6.18 Freedom of Religion 6.25 Religious Groups 6.28 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.29 Political Activists – UNITA 6.43