View Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

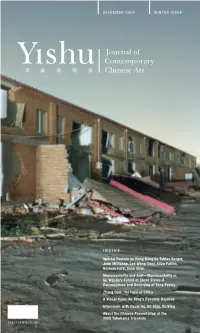

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

University of California, San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Comparative Literature by Xiangyang Liu Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Wai-lim Yip 2010 The Thesis of Xiangyang Liu is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents…………….…………………………………………………...… iv Abstract………………………………………………………………..…................ v Introduction…………………………………………………………… …………... 1 Chapter One A Modern City in the Perspective of Two Generations……………………………... 3 Chapter Two Urban Culture: Transmission and circling………………………………………….. 27 Chapter Three Negotiation with Shanghai’s Present and Past…………………………………….... 51 Conclusion………………………...………………………………………………… 86 Bibliography..……………………..…………………………………………… …….. 90 iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film by Xiangyang Liu Master of Arts in Comparative Literature University of California, San Diego, 2010 Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair This thesis is intended to investigate a series of films produced since the 1990s. All of these films deal with -

Cheung, Leslie (1956-2003) by Linda Rapp

Cheung, Leslie (1956-2003) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2003, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Leslie Cheung first gained legions of fans in Asia as a pop singer. He went on to a successful career as an actor, appearing in sixty films, including the award-winning Farewell My Concubine. Androgynously handsome, he sometimes played sexually ambiguous characters, as well as romantic leads in both gay- and heterosexually-themed films. Leslie Cheung, born Cheung Kwok-wing on September 12, 1956, was the tenth and youngest child of a Hong Kong tailor whose clients included Alfred Hitchcock and William Holden. At the age of twelve Cheung was sent to boarding school in England. While there he adopted the English name Leslie, in part because he admired Leslie Howard and Gone with the Wind, but also because the name is "very unisex." Cheung studied textiles at Leeds University, but when he returned to Hong Kong, he did not go into his father's profession. He entered a music talent contest on a Hong Kong television station and took second prize with his rendition of Don McLean's American Pie. His appearance in the contest led to acting roles in soap operas and drama series, and also launched his singing career. After issuing two poorly received albums, Day Dreamin' (1977) and Lover's Arrow (1979), Cheung hit it big with The Wind Blows On (1983), which was a bestseller in Asia and established him as a rising star in the "Cantopop" style. He would eventually make over twenty albums in Cantonese and Mandarin. -

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE:Vietnam Veterans Memorial LOCATION: Washington, D.C., U.S. DATE: . 1982 C.E. ARTIST: Maya Lin PERIOD/STYLE: Minimalism PATRON: The Commision of Fine Arts MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: Granite FORM: Highly reflective black granite with incised names of 58,000 names ofVietnam Veterans who sacrificed their lives during the conflict. The name is an abstraction that means more to the family and friends than a pictorial representation. The two walls start very short and get progressively taller until they meet at an oblique angle at the monument’s center. One wall points towards the Washington Monument; the other points to the Lincoln Memorial. FUNCTION: It functions as a memorial to the soldiers that died during the Vietnam War. It is an ideal place for people to come and spend quiet time reflecting on the names and perhaps leaving mementos to the deceased. CONTENT: The walls are made of a dark igneous rock called gabbro, a type of granite, which is highly reflective when polished.The surface of the monument is etched with the 58,195 names of the Americans who died or remained missing in action in the Vietnam War. The names are listed in the order in which they were reported killed or missing in action. This makes the names harder to find, and re- quires a listing and numeric system of organization for visitors. CONTEXT: There were 1400 anonymous entries for this commission. There was a real backlash once her identity was known because of latent racism in the post Vietnam era. She defended her design in front of the United States Congress, who eventually reached a compro- mise: A group of more “traditional” sculptures, called “The Three Soldiers,” was erected near the monument. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: an Analysis of The

THE CURIOUS CASE OF CHINESE FILM CENSORSHIP: AN ANALYSIS OF THE FILM ADMINISTRATION REGULATIONS by SHUO XU A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Shuo Xu Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Gabriela Martínez Chairperson Chris Chávez Member Daniel Steinhart Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2017 ii © 2017 Shuo Xu iii THESIS ABSTRACT Shuo Xu Master of Arts School of Journalism and Communication December 2017 Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations The commercialization and global transformation of the Chinese film industry demonstrates that this industry has been experiencing drastic changes within the new social and economic environment of China in which film has become a commodity generating high revenues. However, the Chinese government still exerts control over the industry which is perceived as an ideological tool. They believe that the films display and contain beliefs and values of certain social groups as well as external constraints of politics, economy, culture, and ideology. This study will look at how such films are banned by the Chinese film censorship system through analyzing their essential cinematic elements, including narrative, filming, editing, sound, color, and sponsor and publisher. -

0Ca60ed30ebe5571e9c604b661

Mark Parascandola ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI Cofounders: Taj Forer and Michael Itkoff Creative Director: Ursula Damm Copy Editors: Nancy Hubbard, Barbara Richard © 2019 Daylight Community Arts Foundation Photographs and text © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai and Notes on the Locations © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai: Images of a Film Industry in Transition © 2019 by Michael Berry All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-942084-74-7 Printed by OFSET YAPIMEVI, Istanbul No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of copyright holders and of the publisher. Daylight Books E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.daylightbooks.org 4 5 ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI: IMAGES OF A FILM INDUSTRY IN TRANSITION Michael Berry THE SOCIALIST PERIOD Once upon a time, the Chinese film industry was a state-run affair. From the late centers, even more screenings took place in auditoriums of various “work units,” 1940s well into the 1980s, Chinese cinema represented the epitome of “national as well as open air screenings in many rural areas. Admission was often free and cinema.” Films were produced by one of a handful of state-owned film studios— tickets were distributed to employees of various hospitals, factories, schools, and Changchun Film Studio, Beijing Film Studio, Shanghai Film Studio, Xi’an Film other work units. While these films were an important part of popular culture Studio, etc.—and the resulting films were dubbed in pitch-perfect Mandarin during the height of the socialist period, film was also a powerful tool for education Chinese, shot entirely on location in China by a local cast and crew, and produced and propaganda—in fact, one could argue that from 1949 (the founding of the almost exclusively for mainland Chinese film audiences. -

Impeded Language in EE Cummings' Poetry and Xu

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1995 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky Anna Neher Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Neher, Anna, "Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky" (1995). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 262. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/262 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY An equal opportunity university Honors■ Program HONORS THESIS In presenting this Honors paper in partial requirements for a bachelor ’s degree at Western Washington University, 1 agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood that any publication of this thesis for commercial purposes or for financial 2 ain shall not be allowed without mv written permission. Signature Date G- Anna Neher 1 Anna Neher Dr. Melissa Walt Honors Senior Project June 10, 2005 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky ”In the twentieth century as never before, form calls attention to itself.. -

Festival Schedule

T H E n OR T HWEST FILM CE n TER / p ORTL a n D a R T M US E U M p RESE n TS 3 3 R D p ortl a n D I n ter n a tio n a L film festi v a L S p O n SORED BY: THE OREGO n I a n / R E G a L C I n EM a S F E BR U a R Y 1 1 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 0 WELCOME Welcome to the Northwest Film Center’s 33rd annual showcase of new world cinema. Like our Northwest Film & Video Festival, which celebrates the unique visions of artists in our community, PIFF seeks to engage, educate, entertain and challenge. We invite you to explore and celebrate not only the art of film, but also the world around you. It is said that film is a universal language—able to transcend geographic, political and cultural boundaries in a singular fashion. In the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous observation, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler who is foreign,” this year’s films allow us to discover what unites rather than what divides. The Festival also unites our community, bringing together culturally diverse audiences, a remarkable cross-section of cinematic voices, public and private funders of the arts, corporate sponsors and global film industry members. This fabulous ecology makes the event possible, and we wish our credits at the back of the program could better convey our deep appreci- ation of all who help make the Festival happen. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

Ualbany Art Museum Marks Its 50Th Year Venue Helped Energize Local Art Scene

UAlbany art museum marks its 50th year Venue helped energize local art scene By Amy Biancolli on October 22, 2017 Jason Middlebrook's "Live with Less," his 2009 installation at the UAM (image courtesy University at Albany / University Art Museum) Fifty years ago, an airy new venue for contemporary art opened up in Albany, one among the many modernist structures sprawled in the new uptown SUNY campus designed by the architect Edward Durell Stone. The museum was spacious and bright with windows, light spilling into upstairs and downstairs galleries ringing an open, soaring atrium that reached 35 feet to the roof. Its inaugural exhibit, which opened Oct. 5, 1967, featured paintings and sculptures from the collection of Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, the governor of New York and the state's most famous patron of abstract- expressionist artwork. "It really changed the contemporary landscape for our region — really, forever," said Tammis K. Groft, executive director of the Albany Institute of History and Art, the venerable museum best known for its cultural artifacts and collection of 19th-century Hudson River School paintings. SUNY's new cultural bastion of poured concrete cracked open a local arts scene more focused on the past than the present and future: the Institute was the old guard, slanted toward history. In the years since UAM opened, several regional havens for contemporary art have sprung into being. Among them: Albany Center Gallery in 1977. The Rice Gallery at the Albany Institute of History & Art, 1982. Mass MoCA, 1999. The Tang, 2000. The Opalka Gallery at Sage, 2002. "There are many more organizations focused on contemporary art" around the region these days, said Janet Riker, former director. -

Chinese Cinema and Transnational Cultural Politics : Reflections on Film Estivf Als, Film Productions, and Film Studies

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 2 Issue 1 Vol. 2.1 二卷一期 (1998) Article 6 7-1-1998 Chinese cinema and transnational cultural politics : reflections on film estivf als, film productions, and film studies Yingjin ZHANG Indiana University, Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Zhang, Y. (1998). Chinese cinema and transnational cultural politics: Reflections on filmestiv f als, film productions, and film studies. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 2(1), 105-132. This Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Chinese Cinema and Transnational Cultural Politics: Reflections on Film Festivals, Film Productions, and Film Studies Yingjin Zhang This study situates Chinese cinema among three interconnected concerns that all pertain to transnational cultural politics: (1) the impact of international film festivals on the productions of Chinese films and their reception in the West; (2) the inadequacy of the “Fifth Generation” as a critical term for Chinese film studies; and (3) the need to address the current methodological confinement in Western studies of Chinese cinema. By “transnational cultural politics” here I mean the complicated——and at times complicit— ways Chinese films, including those produced in or coproduced with Hong Kong and Taiwan, are enmeshed in tla larger process in which popular- cultural technologies, genres, and works are increasingly moving and interacting across national and cultural borders” (During 1997: 808).