DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Sample Pages

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 51 F M" INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-J UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY c::<::s CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Cross-Cultural Readings of Chineseness Narratives, Images, and Interpretations of the 1990s EDITED BY Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cross-cultural readings of Chineseness : narratives, images, and interpretations of the 1990s I edited by Wen-hsin Yeh. p. em. - (China research monograph; 51) Collection of papers presented at the conference "Theoretical Issues in Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies". Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-55729-064-4 1. Chinese literature-20th century-History and criticism Congresses. 2. Arts, Chinese-20th century Congresses. 3. Motion picture-History and criticism Congresses. 4. Postmodernism-China Congresses. I. Yeh, Wen-hsin. -

Big Business, Selling Shrimps: the Market As Imaginary in Post-Mao

For decades critics have written disapprovingly about the relationship between the market and art. In the 1970s proponents of institutional critique wrote in Artforum about the degrading effects of money on art, and in the 1980s Robert Hughes (author of Shock of the New and director of The Mona Lisa Curse) compared the 01/07 deleterious effect of the market on art to that of strip-mining on nature.1ÊMore recently, Hal Foster has disparaged the work of some of the markets hottest art stars – Takashi Murakami, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons – declaring that their pop concoctions lack tension, critical distance, and irony, offering little more than “giddy delight, weary despair, or a manic- Jane DeBevoise depressive cocktail of the two.”2 And Walter Robinson has spoken about the ability of the market to act as a kind of necromancer, Big Business, reanimating mid-century styles of abstract painting for the purposes of flipping canvas like Selling real estate – a phenomenon he calls “zombie formalism.”3 Shrimps: The ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊMoralistic attacks against the degrading impact of the market on art are not unique to US- based critics. Soon after the end of the Cultural Market as Revolution, when few people think China had any art market at all, plainly worded attacks on Imaginary in commercialism appeared regularly in the nationally circulated art press. As early as 1979, a n i Jiang Feng, the chair of the Chinese Artists h Post-Mao China C Association, worried in writing that ink painters o a were churning out inferior works in pursuit of M - t 4 s material gain.Ê ÊIn 1983, the conservative critic o P Hai Yuan wrote that “owing to the opportunity for n i y high profit margins, many painters working in oil r a n or other mediums have switched to ink painting.” i g e a s And, what was worse, to maximize their gain, i m o I v these artists “sought to boost their productivity s e a B 5 t e by acting like walking photocopy machines.” In e D k e r the 1990s supporters of experimental oil a n a M painting also came under fire. -

Item for Finance Committee

For discussion FCR(2013-14)23 on 21 June 2013 ITEM FOR FINANCE COMMITTEE HEAD 95 – LEISURE AND CULTURAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT New Subhead “Acquiring and Commissioning Artworks by Local Artists” New Item “Acquiring and Commissioning Artworks by Local Artists” Members are invited to approve a new commitment of $50 million under a new subhead to be created under Head 95 Leisure and Cultural Services Department for acquiring and commissioning artworks by local artists. PROBLEM To foster the development of visual arts and nurture local artistic talent in the field, we need to provide additional funding for acquiring and commissioning more artworks by local artists. PROPOSAL 2. The Director of Leisure and Cultural Services (DLCS), with the support of the Secretary for Home Affairs (SHA), proposes to create a new commitment of $50 million for the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) to acquire and commission artworks by local artists. JUSTIFICATION 3. It is the Government’s cultural policy to develop Hong Kong into an international cultural metropolis. To achieve this policy objective, LCSD has been making continued efforts in nurturing artistic talent. To strengthen the development of visual arts and groom local artists in the area of visual arts, we consider it important to provide artists with opportunities to showcase their artworks on a frequent and continual basis. One of the most effective means is to acquire their /artworks ….. FCR(2013-14)23 Page 2 artworks and display them in our public museums, and commission their artworks for public arts projects. This could help promote their profile and build their audience, which provides a solid basis for their development in the arts sector. -

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE:Vietnam Veterans Memorial LOCATION: Washington, D.C., U.S. DATE: . 1982 C.E. ARTIST: Maya Lin PERIOD/STYLE: Minimalism PATRON: The Commision of Fine Arts MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: Granite FORM: Highly reflective black granite with incised names of 58,000 names ofVietnam Veterans who sacrificed their lives during the conflict. The name is an abstraction that means more to the family and friends than a pictorial representation. The two walls start very short and get progressively taller until they meet at an oblique angle at the monument’s center. One wall points towards the Washington Monument; the other points to the Lincoln Memorial. FUNCTION: It functions as a memorial to the soldiers that died during the Vietnam War. It is an ideal place for people to come and spend quiet time reflecting on the names and perhaps leaving mementos to the deceased. CONTENT: The walls are made of a dark igneous rock called gabbro, a type of granite, which is highly reflective when polished.The surface of the monument is etched with the 58,195 names of the Americans who died or remained missing in action in the Vietnam War. The names are listed in the order in which they were reported killed or missing in action. This makes the names harder to find, and re- quires a listing and numeric system of organization for visitors. CONTEXT: There were 1400 anonymous entries for this commission. There was a real backlash once her identity was known because of latent racism in the post Vietnam era. She defended her design in front of the United States Congress, who eventually reached a compro- mise: A group of more “traditional” sculptures, called “The Three Soldiers,” was erected near the monument. -

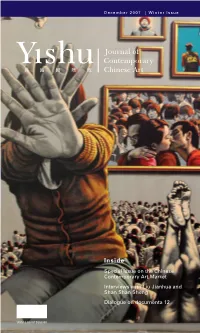

Inside Special Issue on the Chinese Contemporary Art Market Interviews with Liu Jianhua and Shan Shan Sheng Dialogue on Documenta 12

December 2007 | Winter Issue Inside Special Issue on the Chinese Contemporary Art Market Interviews with Liu Jianhua and Shan Shan Sheng Dialogue on documenta 12 US$12.00 NT$350.00 china square 1 2 Contents 4 Editor’s Note 6 Contributors 8 Contemporary Chinese Art: To Get Rich Is Glorious 11 Britta Erickson 17 The Surplus Value of Accumulation: Some Thoughts Martina Köppel-Yang 19 Seeing Through the Macro Perspective: The Chinese Art Market from 2006 to 2007 Zhao Li 23 Exhibition Culture and the Art Market 26 Yü Christina Yü 29 Interview with Zheng Shengtian at the Seven Stars Bar, 798, Beijing Britta Erickson 34 Beyond Selling Art: Galleries and the Construction of Art Market Norms Ling-Yun Tang 44 Taking Stock Joe Martin Hill 41 51 Everyday Miracles: National Pride and Chinese Collectors of Contemporary Art Simon Castets 58 Superfluous Things: The Search for “Real” Art Collectors in China Pauline J. Yao 62 After the Market’s Boom: A Case Study of the Haudenschild Collection 77 Michelle M. McCoy 72 Zhong Biao and the “Grobal” Imagination Paul Manfredi 84 Export—Cargo Transit Mathieu Borysevicz 90 About Export—Cargo Transit: An Interview with Liu Jianhua 87 Chan Ho Yeung David 93 René Block’s Waterloo: Some Impressions of documenta 12, Kassel Yang Jiechang and Martina Köppel-Yang 101 Interview with Shan Shan Sheng Brandi Reddick 109 Chinese Name Index 108 Yishu 22 errata: On page 97, image caption lists director as Liang Yin. Director’s name is Ying Liang. On page 98, image caption lists director as Xialu Guo. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Impeded Language in EE Cummings' Poetry and Xu

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1995 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky Anna Neher Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Neher, Anna, "Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky" (1995). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 262. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/262 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY An equal opportunity university Honors■ Program HONORS THESIS In presenting this Honors paper in partial requirements for a bachelor ’s degree at Western Washington University, 1 agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood that any publication of this thesis for commercial purposes or for financial 2 ain shall not be allowed without mv written permission. Signature Date G- Anna Neher 1 Anna Neher Dr. Melissa Walt Honors Senior Project June 10, 2005 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky ”In the twentieth century as never before, form calls attention to itself.. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

LC Paper No. CB(2)802/12-13(05)

LC Paper No. CB(2)802/12-13(05) For information on 22 March 2013 Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs Measures to Enhance Public Museum Services Purpose This paper updates Members on the progress made to enhance the services of public museums under the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD). Progress Made on Enhancement of Public Museum Services 2. There are 14 public museums1 being managed by LCSD. Since 2010, LCSD has set eight new directions for museum development with the aim of delivering museum services with greater transparency, accountability, efficiency and creativity so as to meet the changing aspirations of the community. 3. With the expert advice given by museum advisors and the concerted efforts of museum staff, many of the programmes organised by the museums in the past few years have received overwhelming response, as evident from the record breaking attendance of 5.8 million visitors and 1.17 million people taking part in the education and extension programmes organised by the museums in 2012. The new directions set for the museums and the progress made in the past three years (2010-2012) are summarised in the ensuing paragraphs. (a) Enhancing Public Accountability and Transparency (i) Museum Advisory Panels 4. To enhance public accountability and involvement in the management of museums, three Museum Advisory Panels (MAPs) for the Art, History and Science 1 The 14 museums are Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong Museum of History, Hong Kong Heritage Museum, Hong Kong Science Museum, Hong Kong Space Museum, Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware, Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum, Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence, Fireboat Alexander Grantham Exhibition Gallery, Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb Museum, Law Uk Folk Museum, Sam Tung Uk Museum, Hong Kong Railway Museum and Sheung Yiu Folk Museum. -

Big-Character Posters, Red Logorrhoea and the Art of Words

History Writ Large: Big-character Posters, Red Logorrhoea and the Art of Words Geremie R. Barmé, Australian National University In 1986, the Zhoushan-based artist Wu Shanzhuan worked with other recent art school graduates to create an installation called ‘Red Humour’ (hongse youmo 红色幽默). It featured a room covered in the graffiti-like remnants of big-character posters (dazi bao 大 字报) that recalled the Cultural Revolution when hand-written posters replete with vitriol and denunciations of the enemies of Mao Zedong Thought were one of the main cultural weapons in the hands of revolutionary radicals (Figure 1). It was an ironic attempt to recapture the overwhelming and manic mood engendered by the red sea of big-character posters that swelled up in Beijing from mid 1966 and developed into a movement to ‘paint the nation red’ with word-images during the second half of that year and in 1967. In the reduced and concentrated form of an art installation Wu attempted to replicate the stifling environment of the written logorrhoea of High-Maoist China (Figure 2). Figure 1: ‘Red Humor,’ Wu Shanzhuan. Source: Gao Minglu (2008) ’85 Meishu Yundong—80 niandaide renwen qianwei, Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe, Guilin, vol. 1. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol. 9, no. 3, November 2012. Politics and Aesthetics in China Special Issue, guest edited by Maurizio Marinelli. ISSN: 1449-2490; http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/portal PORTAL is published under the auspices of UTSePress, Sydney, Australia. Barmé History Writ Large Figure 2: Red Sea, Beijing 1967. Source: Long Bow Archive, Boston. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Proposed Museum Expert Advisers for 2006/07

Museum Expert Advisers (1 April 2020 to 31 March 2022) Museum expert advisers are appointed by the Director of Leisure and Culture Services for a period of two years to provide professional advice to the museums of the Leisure and Cultural Services Department on matters pertaining to the promotion of art, history, science and film, in particular the acquisition of collection items. Advisers specialising in the field of art and history are as follows: (Names are listed in alphabetical order) Art Name Professional Background Hong Kong Art The late Mr Gaylord Co-founder and first Chairman, Hong Kong Visual Arts CHAN, MBE, BBS Society (1974) Co-founder, Culture Corner Art Academy (1989) Co-founder, Artmatch Group (1995) Prof CHAN Yuk Adjunct Professor, Department of Fine Arts, The Chinese Keung University of Hong Kong Prof CHANG Ping Architect Hung, Wallace Chairman, 1a space Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, The University of Hong Kong Prof David CLARKE Honorary Professor, Department of Fine Arts, The University of Hong Kong Dr Anissa FUNG Former Associate Professor, The Education University of Hong Kong Ceramic Artist Products Design and Development Consultant Mr FUNG Ho Yin Visiting Lecturer, School of Design, Hong Kong Polytechnic University Chairman, Hong Kong Open Printshop Mr FUNG Hon Kee, Programme Leader/ Lecturer, Postgraduate Diploma in Joseph Photography, HKU School of Professional and Continuing Education Honorary Advisor and Founding Member, Hong Kong Photographic Culture Association - Name Professional