Inside Special Issue on the Chinese Contemporary Art Market Interviews with Liu Jianhua and Shan Shan Sheng Dialogue on Documenta 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

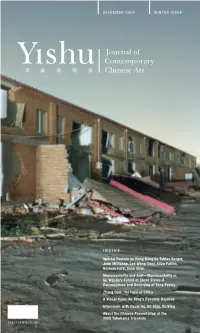

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts Presents: Abbas Akhavan: Cast for a Folly May 9 Through July 27, 2019 Curated by CCA Wattis Institute Curator Kim Nguyen

CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts presents: Abbas Akhavan: cast for a folly May 9 through July 27, 2019 Curated by CCA Wattis Institute curator Kim Nguyen Akosua Adoma Owusu: Welcome to the Jungle May 9 through July 27, 2019 Curated by CCA Wattis Institute curator Kim Nguyen Above: Abbas Akhavan, Study for a Garden: Fountain (installation view, Delfina Foundation, London), 2012. Oscillating water sprinkler, pump, hose, pvc pond liner, water, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver. Photo: Christa Holka. Below: Akosua Adoma Owusu, Split Ends, I Feel Wonderful, 2012 (still). 16mm film transfer to video, 4 mins. Courtesy of the artist. San Francisco, CA—March 12, 2019—CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts proudly presents two new solo exhibitions, Abbas Akhavan: cast for a folly and Akosua Adoma Owusu: Welcome to the Jungle. For multi- disciplinary artist Abbas Akhavan, this exhibition is his first U.S. solo show and the culmination of his year as the 2018–2019 Capp Street Artist-in- Residence. Ghanaian-American filmmaker Akosua Adoma Owusu will present a medley of her films in an installation format—new territory for Owusu—in which two of her films will have their institutional premiere at CCA Wattis. Although these are two independent shows, both artists navigate histories, identities, politics, and materiality through distinct international lenses. “We are thrilled to present the newest works by each of these incredible artists,” says Kim Nguyen, CCA Wattis Institute curator and head of programs. “Abbas Akhavan’s time and attention to place made him a perfect fit for the Capp Street residency, where he can really delve into the ethos of San Francisco and its communities. -

Big Business, Selling Shrimps: the Market As Imaginary in Post-Mao

For decades critics have written disapprovingly about the relationship between the market and art. In the 1970s proponents of institutional critique wrote in Artforum about the degrading effects of money on art, and in the 1980s Robert Hughes (author of Shock of the New and director of The Mona Lisa Curse) compared the 01/07 deleterious effect of the market on art to that of strip-mining on nature.1ÊMore recently, Hal Foster has disparaged the work of some of the markets hottest art stars – Takashi Murakami, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons – declaring that their pop concoctions lack tension, critical distance, and irony, offering little more than “giddy delight, weary despair, or a manic- Jane DeBevoise depressive cocktail of the two.”2 And Walter Robinson has spoken about the ability of the market to act as a kind of necromancer, Big Business, reanimating mid-century styles of abstract painting for the purposes of flipping canvas like Selling real estate – a phenomenon he calls “zombie formalism.”3 Shrimps: The ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊMoralistic attacks against the degrading impact of the market on art are not unique to US- based critics. Soon after the end of the Cultural Market as Revolution, when few people think China had any art market at all, plainly worded attacks on Imaginary in commercialism appeared regularly in the nationally circulated art press. As early as 1979, a n i Jiang Feng, the chair of the Chinese Artists h Post-Mao China C Association, worried in writing that ink painters o a were churning out inferior works in pursuit of M - t 4 s material gain.Ê ÊIn 1983, the conservative critic o P Hai Yuan wrote that “owing to the opportunity for n i y high profit margins, many painters working in oil r a n or other mediums have switched to ink painting.” i g e a s And, what was worse, to maximize their gain, i m o I v these artists “sought to boost their productivity s e a B 5 t e by acting like walking photocopy machines.” In e D k e r the 1990s supporters of experimental oil a n a M painting also came under fire. -

WSJ Vanishing Asia062708.Pdf

0vtdt0vtdt ASIAN ARTS & CULTURE SPECIAL Q`tjhjtf -j` 10 Mhd pdf`b ve C`p`bb` 16 ;tcj` 0hjtdd cj`wv}` 19 8vtf jt .djkjtf -}aj}`fd w}jbd bhdbm 3 ¡ 5`hjvt 25 ¡ M`d 28 ¡ 8j Aj Jddt ve hd c}`wd Mhd `} ve fp` jt =`w`t 0vtdqwv}`} 4 ¡ Lwv} 26 ¡ Mjqd Gee `}j 5dtf Zhdtfkjd vw .}jtf j vtª av 0j}b jt .djkjtf Avtcvt `} qdq 6 ¡ 5vvc 1}jtm Kv`p .`ppd jt 8vtf ?vtf 1jtd l.d` hd Mhd 1jhI 8`tvj whv .d` qjb`p jt ?`p` H`w` 1vapd Aqw} lTjbmdc qjb`p 8 ¡ M}`dp jt Cdpav}td 0dppv bvtbd} 0j T`pmI 8vtf ?vtf jt Ldvp 5jpq edj`p jt 24 ¡ .vvm Lctd Kjd}c`tbd v} -j` O}a`t pdfdtc WSJ.com Cover: A 1930s photograph found torn and discarded in a Malacca Weekend Journal online building (Lim Huck Chin and See slideshows of Malacca’s heritage Fernando Jorge) S. Karene Witcher Editor and India’s Chinese diaspora, plus This page: Ng Ah Kee at the Sin view a video of our latest City Walk— Jessica Yu News graphics director See Tai barbershop in Malacca (Lim David Chan Hong Kong—at WSJ.com/Travel Art director Huck Chin and Fernando Jorge), Mary E. Kissel Taste page editor top; Shockers cheerleading team email [email protected] For more on Japan’s all-male (Steve West), left; ‘Pies de Plomo cheerleading squad Shockers, see (Zapateado Luz),’ by Rubén Ramos ? x {t WSJ.com/Sports Balsa (Rubén Ramos Balsa), right M83 T-AA LMK33M =GOKE-A -L;-+ 5`hjvt Dresses by Madame Grès show her signature draping, left, and kimono sleeves, right; New York vintage collector Juliana Cairone, Mhd pv fvccdd center, at her store How a rare collection of vintage gowns was found . -

Ingram 2010 Squatting in 'Vancouverism'

designs for The Terminal City www.gordonbrentingram.ca/theterminalcity 21 March, 2010 Gordon Brent Ingram Re-casting The Terminal City [part 3] Squatting in 'Vancouverism': Public art & architecture after the Winter Olympics Public art was part of the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver; there was some funding, some media coverage, and a few sites were transformed. What were the new spaces created and modes of cultural production, in deed the use of 21 March, 2010 | Gordon Brent Ingram Squatting in 'Vancouverism': Public art & architecture after the Winter Olympics designs for The Terminal City www.gordonbrentingram.ca/theterminalcity page 2 culture in Vancouver, that have emerged in this winter of the Olympics? What lessons can be offered, if any, to other contemporary arts and design communities in Canada and elsewhere? And there was such celebration of Vancouver, that a fuzzy construct was articulated for 'Vancouverism' that today has an unresolved and sometimes pernicious relationship between cultural production and the dynamics between public and privatizing art. In this essay, I explore when, so far, 'Vancouverism'1 has become a cultural, design, 'planning', or ideological movement and when the term has been more of a foil for marketing over‐priced real estate.2 In particular, I am wondering what, in these supposedly new kinds of Vancouveristic urban designs, are the roles, 'the place' of public and other kinds of site‐based art. The new Woodward's towers and the restored Woodward's W sign from the historic centre of 19th Century Vancouver at Carrall and Water Street, January 2010, photograph by Gordon Brent Ingram 21 March, 2010 | Gordon Brent Ingram Squatting in 'Vancouverism': Public art & architecture after the Winter Olympics designs for The Terminal City www.gordonbrentingram.ca/theterminalcity page 3 January and February 2010 were the months to separate fact from fiction and ideas from hyperbole. -

15 February 2020, Cape Town

CONTEMPORARY ART 15 February 2020 CT 2020/1 2 Contemporary Art including the Property of a Collector Saturday 15 February 2020 at 6 pm Bubbly and canapés from 5 pm VEnuE abSEntEE anD TELEPHonE biDS Quay 7 Warehouse, 11 East Pier Road Tel +27 (0) 21 683 6560 V&A Waterfront, Cape Town +27 (0) 78 044 8185 GPS Co-ordinates: 33°54’05.4”S 18°25’27.9”E [email protected] PREVIEW payMEnt Thursday 13 and Friday 14 February Tel +27 (0) 21 683 6560 from 10 am to 5 pm +27 (0) 11 728 8246 Saturday 15 February from 10 am to 6 pm [email protected] LEctuRES anD WalKaboutS conDition REpoRTS See page 10 [email protected] ENQuiRIES anD cataloGUES www.straussart.co.za +27 (0) 21 683 6560 +27 (0) 78 044 8185 contact nuMBERS DURinG PREVIEW anD auction ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE: R220.00 Tel +27 (0) 78 044 8185 All lots are sold subject to the conditions of business +27 (0) 72 337 8405 printed at the back of ths catalogue PUBLIC AUCTION BY DIRECTORS F KILBOURN (EXECUTIVE CHAIRPERSON), E BRADLEY, CB STRAUSS, C WIESE, J GINSBERG, C WELZ, V PHILLIPS (MD), B GENOVESE (MD), AND S GOODMAN (EXECUTIVE) 4 Contents 3 Sale Information 6 Directors, Specialists, Administration 8 Map and Directions 9 Buying at Strauss & Co 10 Lectures and Walkabouts 12 Contemporary Art Auction at 6pm Lots 1–102 121 Conditions of Business 125 Bidding Form 126 Shipping Instruction Form 132 Artist Index PAGE 2 Lot 21 Yves Klein Table IKB® (detail) LEFT Lot 53 William Kentridge Small Koppie 2 (detail) From the Property of a Collector 5 Directors Specialists Administration -

Lucy Sparrow Photo: Dafydd Jones 18 Hot &Coolart

FREE 18 HOT & COOL ART YOU NEVER FELT LUCY SPARROW LIKE THIS BEFORE DAFYDD JONES PHOTO: LUCY SPARROW GALLERIES ONE, TWO & THREE THE FUTURE CAN WAIT OCT LONDON’S NEW WAVE ARTISTS PROGRAMME curated by Zavier Ellis & Simon Rumley 13 – 17 OCT - VIP PREVIEW 12 OCT 6 - 9pm GALLERY ONE PETER DENCH DENCH DOES DALLAS 20 OCT - 7 NOV GALLERY TWO MARGUERITE HORNER CARS AND STREETS 20 - 30 OCT GALLERY ONE RUSSELL BAKER ICE 10 NOV – 22 DEC GALLERY TWO NEIL LIBBERT UNSEEN PORTRAITS 1958-1998 10 NOV – 22 DEC A NEW NOT-FOR-PROFIT LONDON EXHIBITION PLATFORM SUPPORTING THE FUSION OF ART, PHOTOGRAPHY & CULTURE Art Bermondsey Project Space, 183-185 Bermondsey Street London SE1 3UW Telephone 0203 441 5858 Email [email protected] MODERN BRITISH & CONTEMPORARY ART 20—24 January 2016 Business Design Centre Islington, London N1 Book Tickets londonartfair.co.uk F22_Artwork_FINAL.indd 1 09/09/2015 15:11 THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com EXHIBITIONS WIFREDO ARCAY CUBAN STRUCTURES THE MAYOR GALLERY 13 OCT - 20 NOV Wifredo Arcay (b. 1925, Cuba - d. 1997, France) “ETNAIRAV” 1959 Latex paint on plywood relief 90 x 82 x 8 cm 35 1/2 x 32 1/4 x 3 1/8 inches WOJCIECH FANGOR WORKS FROM THE 1960s FRIEZE MASTERS, D12 14 - 18 OCT Wojciech Fangor (b.1922, Poland) No. 15 1963 Oil on canvas 99 x 99 cm 39 x 39 inches STATE_OCT15.indd 1 03/09/2015 15:55 CAPTURED BY DAFYDD JONES i SPY [email protected] EWAN MCGREGOR EVE MAVRAKIS & Friend NICK LAIRD ZADIE SMITH GRAHAM NORTON ELENA SHCHUKINA ALESSANDRO GRASSINI-GRIMALDI SILVIA BRUTTINI VANESSA ARELLE YINKA SHONIBARE NIMROD KAMER HENRY HUDSON PHILIP COLBERT SANTA PASTERA IZABELLA ANDERSSON POPPY DELEVIGNE ALEXA CHUNG EMILIA FOX KARINA BURMAN SOPHIE DAHL LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE CHIWETEL EJIOFOR EVGENY LEBEDEV MARC QUINN KENSINGTON GARDENS Serpentine Gallery summer party co-hosted by Christopher Kane. -

The Economist Print Edition

The Pop master's highs and lows Nov 26th 2009 From The Economist print edition Andy Warhol is the bellwether The Andy Warhol Foundation $100m-worth of Elvises “EIGHT ELVISES” is a 12-foot painting that has all the virtues of a great Andy Warhol: fame, repetition and the threat of death. The canvas is also awash with the artist’s favourite colour, silver, and dates from a vintage Warhol year, 1963. It did not leave the home of Annibale Berlingieri, a Roman collector, for 40 years, but in autumn 2008 it sold for over $100m in a deal brokered by Philippe Ségalot, the French art consultant. That sale was a world record for Warhol and a benchmark that only four other artists—Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning and Gustav Klimt— have ever achieved. Warhol’s oeuvre is huge. It consists of about 10,000 artworks made between 1961, when the artist gave up graphic design, and 1987, when he died suddenly at the age of 58. Most of these are silk-screen paintings portraying anything from Campbell’s soup cans to Jackie Kennedy and Mao Zedong, drag queens and commissioning collectors. Warhol also created “disaster paintings” from newspaper clippings, as well as abstract works such as shadows and oxidations. The paintings come in series of various sizes. There are only 20 “Most Wanted Men” canvases, for example, but about 650 “Flower” paintings. Warhol also made sculpture and many experimental films, which contribute greatly to his legacy as an innovator. The Warhol market is considered the bellwether of post-war and contemporary art for many reasons, including its size and range, its emblematic transactions and the artist’s reputation as a trendsetter. -

Asian Canadian Art and Artists Bibliography

ASIAN CANADIAN ART AND ARTISTS BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by the Ethnocultural Art Histories Research group (EAHR) Founded in 2011, The Ethnocultural Art Histories Research group (EAHR) is a student-led research community that facilitates opportunities for exchange and research-creation in the examination of issues of ethnic and cultural representation within the visual arts in Canada. Based within the Department of Concordia University, EAHR leads an annual public programming agenda of symposia, artist talks, public lectures, and curatorial projects as a means to disseminate knowledge and provoke discussion. Allen, Jan and Baerwaldt, Wayne. Germaine Koh : Personal. Kingston, ON: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 1997. Anon.. Gu Xiong : The Mirror : A Return To China. Whitehorse, YT: Yukon Arts Centre, 1999. Anon.. The Lab 6.2 : Ho Tam : Romances. Victoria, BC: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 2006. Anon.. Lost Secrets of the Royal : SoJin Chun, Louise Noguchi. Toronto, ON: A Space Gallery, 2011. Anon.. Resistance is Fertile : Dana Claxton ; Thirza Cuthand ; Richard Fung ; Shani Mootoo ; Ho Tam ; Paul Wong. Toronto, ON: A. Space Gallery, 2010. Anon.. REviewing the Mosaic : Canadian Video Artists Speaking Through Race. Saskatoon, SK: Mendel Art Gallery, 1995. Anon. Seven Years in Korea. Seoul, South Korea: Dongsoong Cinematheque, 1999. Anon.. Strangers in a Strange Land. Regina, Sask.: Rosemont Art Gallery, 2001. Arnold, Grant. Ken Lum. Vancouver BC: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2010. Arnold, Grant and Enwezor, Okwui and Schõny, Roland. Ken Lum. Vancouver BC: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2011. Arnold, Grant and Qiang, Zhang and Li, Jin. Here not There. Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1995. Baden, Mowry. Yoko Takashima. Kamloops, BC: Kamloops Art Gallery; Lethbridge, AB: s.n., 2003. -

Behind the Thriving Scene of the Chinese Art Market -- a Research

Behind the thriving scene of the Chinese art market -- A research into major market trends at Chinese art market, 2006- 2011 Lifan Gong Student Nr. 360193 13 July 2012 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R.Vermeylen Second reader: Dr. Marilena Vecco Master Thesis Cultural economics & Cultural entrepreneurship Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 Abstract Since 2006, the Chinese art market has amazed the world with an unprecedented growth rate. Due to its recent emergence and disparity from the Western art market, it remains an indispensable yet unfamiliar subject for the art world. This study penetrates through the thriving scene of the Chinese art market, fills part of the gap by presenting an in-depth analysis of its market structure, and depicts the route of development during 2006-2011, the booming period of the Chinese art market. As one of the most important and largest emerging art markets, what are the key trends in the Chinese art market from 2006 to 2011? This question serves as the main research question that guides throughout the research. To answer this question, research at three levels is unfolded, with regards to the functioning of the Chinese art market, the geographical shift from west to east, and the market performance of contemporary Chinese art. As the most vibrant art category, Contemporary Chinese art is chosen as the focal art sector in the empirical part since its transaction cover both the Western and Eastern art market and it really took off at secondary art market since 2005, in line with the booming period of the Chinese art market. -

Big-Character Posters, Red Logorrhoea and the Art of Words

History Writ Large: Big-character Posters, Red Logorrhoea and the Art of Words Geremie R. Barmé, Australian National University In 1986, the Zhoushan-based artist Wu Shanzhuan worked with other recent art school graduates to create an installation called ‘Red Humour’ (hongse youmo 红色幽默). It featured a room covered in the graffiti-like remnants of big-character posters (dazi bao 大 字报) that recalled the Cultural Revolution when hand-written posters replete with vitriol and denunciations of the enemies of Mao Zedong Thought were one of the main cultural weapons in the hands of revolutionary radicals (Figure 1). It was an ironic attempt to recapture the overwhelming and manic mood engendered by the red sea of big-character posters that swelled up in Beijing from mid 1966 and developed into a movement to ‘paint the nation red’ with word-images during the second half of that year and in 1967. In the reduced and concentrated form of an art installation Wu attempted to replicate the stifling environment of the written logorrhoea of High-Maoist China (Figure 2). Figure 1: ‘Red Humor,’ Wu Shanzhuan. Source: Gao Minglu (2008) ’85 Meishu Yundong—80 niandaide renwen qianwei, Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe, Guilin, vol. 1. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol. 9, no. 3, November 2012. Politics and Aesthetics in China Special Issue, guest edited by Maurizio Marinelli. ISSN: 1449-2490; http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/portal PORTAL is published under the auspices of UTSePress, Sydney, Australia. Barmé History Writ Large Figure 2: Red Sea, Beijing 1967. Source: Long Bow Archive, Boston. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York.