Raja Ravi Varma 145

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Sample Pages

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 51 F M" INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-J UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY c::<::s CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Cross-Cultural Readings of Chineseness Narratives, Images, and Interpretations of the 1990s EDITED BY Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cross-cultural readings of Chineseness : narratives, images, and interpretations of the 1990s I edited by Wen-hsin Yeh. p. em. - (China research monograph; 51) Collection of papers presented at the conference "Theoretical Issues in Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies". Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-55729-064-4 1. Chinese literature-20th century-History and criticism Congresses. 2. Arts, Chinese-20th century Congresses. 3. Motion picture-History and criticism Congresses. 4. Postmodernism-China Congresses. I. Yeh, Wen-hsin. -

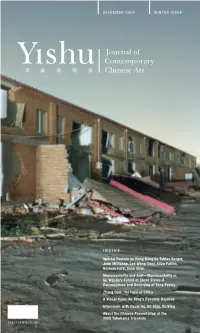

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

And Joydeep Ghosh (Sarod)

The Asian Indian Classical Music Society 51491 Norwich Drive Granger, IN 46530 Concert Announcement Vidushi Mita Nag (sitar) Pandit Joydeep Ghosh (sarod) with Pandit Subhen Chatterjee (Tabla) April 26, 2016, Tuesday, 7.00PM At: the Andrews Auditorium, Geddes Hall University of Notre Dame Cosponsored with the Liu Institute of Asia and Asian Studies Tickets available at gate. General Admission: $10, AICMS Members and ND/SMC faculty: $5, Students: FREE Mita Nag, daughter of the veteran sitarist, Pandit Manilal Nag and granddaughter of Sangeet Acharya Gokul Nag, belongs to the Vishnupur Gharana of Bengal, a school of music that is nearly 300 years old and which is known for its dhrupad style of playing. She was initiated into music at the age of four, and studied with her mother, grandfather and father. She appeared for her debut performance at the age of ten, when she also won the Government of India’s Junior National Talent Search Award. She has given many concert performances, both alone and with her father, in cities in the US, Canada, Japan and Europe as well as in India. Joydeep Ghosh is hailed as one of India’s leading sarod, surshringar and Mohanveena artists. He started his sarod training at the age of five, and has studied with the great masters the late Sangeetacharya Anil Roychoudhury , late Sangeetacharya Radhika Mohan Moitra and Padmabhusan Acharya Buddhadev Dasgupta all of the Shahajahanpur Gharana. He has won numerous awards and fellowships, including those from the Government of India, the title of “Suramani” from the Sur Singar Samsad (Mumbai) and “Swarshree” from Swarankur (Mumbai). -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Teachers Day Program Details 2018 V11

CMANA 4. Time: 12:00 PM to 12:20 PM in association with GCD 2017 Winner The Sringeri Vidya Bharati Foundation, USA Keshav Muralidharan 19th May 2018 from 10:30 AM Onwards (Vocal) Location The Auditorium, Sringeri Vidya Bharati Foundation, 327,Cays Road, Stroudsburg PA 18360 Break Time: 12:30 PM to 01:15 PM 1. Time: 10:30 AM to 10:50 AM GCD 2017 Winner 5. Time: 01:20 PM to 01:40 PM Neharika Murthy GCD 2016 Winner of Padma Srinivasan Prize (Vocal) Srinath Peraganur ((violin)) 2. Time: 11:00 AM to 11:20 AM Local Teacher Group Participation 6. Time: 01:50 PM to 02:10 PM Teacher Name: Teacher Name: Local Teacher Group Participation Bhavani Prakash Prakash Rao Teacher Name: Manjula Ramachandran Participants Participants Krishna Palya Ananth Rayar Sabarinath Manjula Ramachandran Hemant Gosukonda Ramachandran 3. Time: 11:30 AM to 11:50 AM (Veena) (Vocal) (Mridangam) Local Teacher Group Participation Teacher Name: 7. Time: 02:15 PM to 03:00 PM Srividhya Sairam CMANA HONY PATRON PADMA SRINIVASAN AWARD WINNER IN INSTRUMENTAL CATEGORY ( KRITI,ALAPANA AND SWARAM) IN 2017 Participants Vishal Sowmyan Sabari Ramachandran (Violin) (Mridangam) Sanjana Venkatesh Sowmya Venkatesh www.cmana.org 02 8. Time: 03:10 PM to 03:30 PM GCD 2017 Winner Shardul Krishnakumar T S Nandakumar Shri T.S. Nandakumar, an Top grade artist of the All India Radio, hails 9. Time: 03:40 PM to 04:00 PM from the family of the renowned Nadaswaram exponents, Ambalapuzha Brothers of Kerala. He underwent training in percussion Local Teacher Group Participation under Shri Kaithavana Madhavdas in the Gurukulam tradition. -

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE:Vietnam Veterans Memorial LOCATION: Washington, D.C., U.S. DATE: . 1982 C.E. ARTIST: Maya Lin PERIOD/STYLE: Minimalism PATRON: The Commision of Fine Arts MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: Granite FORM: Highly reflective black granite with incised names of 58,000 names ofVietnam Veterans who sacrificed their lives during the conflict. The name is an abstraction that means more to the family and friends than a pictorial representation. The two walls start very short and get progressively taller until they meet at an oblique angle at the monument’s center. One wall points towards the Washington Monument; the other points to the Lincoln Memorial. FUNCTION: It functions as a memorial to the soldiers that died during the Vietnam War. It is an ideal place for people to come and spend quiet time reflecting on the names and perhaps leaving mementos to the deceased. CONTENT: The walls are made of a dark igneous rock called gabbro, a type of granite, which is highly reflective when polished.The surface of the monument is etched with the 58,195 names of the Americans who died or remained missing in action in the Vietnam War. The names are listed in the order in which they were reported killed or missing in action. This makes the names harder to find, and re- quires a listing and numeric system of organization for visitors. CONTEXT: There were 1400 anonymous entries for this commission. There was a real backlash once her identity was known because of latent racism in the post Vietnam era. She defended her design in front of the United States Congress, who eventually reached a compro- mise: A group of more “traditional” sculptures, called “The Three Soldiers,” was erected near the monument. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

PRESS RELEASE Homeward ARPITA SINGH 18 March

D-40 Defence Colony, New Delhi 110024 | T +91-11-24622545/24615368 D-53 Defence Colony, New Delhi - 110024 | T +91-11-46103550/46103551 E [email protected] | W www.vadehraart.com PRESS RELEASE Homeward ARPITA SINGH 18 March – 16 April 2021 D-40 Defence Colony, New Delhi Vadehra Art Gallery is pleased to announce a continuation of our presentation titled Homeward, featuring a recent body of worK by Arpita Singh, which was recently presented as part of On Site, a collaborative exhibition by four leading galleries held at BiKaner House, New Delhi, earlier this month, and is now on view at our modern gallery. Described as a figurative artist and a modernist, Arpita Singh still maKes it a point to stay tuned in to traditional Indian art forms and aesthetics, like miniaturist painting and different forms of folk art, employing them regularly in her work. Afflicted by the problems that are faced each and every day by women in her country and the world in general, Singh paints the range of emotions that she exchanges with these subjects – from sorrow to joy and from suffering to hope – providing a view of the ongoing communication she maintains with them. In this latest body of watercolours on paper and oil paintings, Singh’s cartographical autobiographies assume new dimensions through an intensification of colour, accenting her imagined landscapes with the flourish of expressionist emotion. With compositions foregrounded in movement, Singh tends to emphasize the potential of individual agency operating within collective constraints, though her mapping doesn’t seem to prioritize any one aspect – whether the fictional, mythical, personal, public fact or dream. -

Utopias and Dystopias in World Literature

MEJO The MELOW Journal of World Literature Volume 4 February 2020 ISSN: 2581-5768 A peer-refereed journal published annually by MELOW (The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World) Sunny Pleasure Domes and Caves of Ice: Utopias and Dystopias in World Literature Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang Volume Sub-Editors Neela Sarkar Barnali Saha 1 Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang, Professor of English, Guru Gobind Singh IP University, Delhi Email: [email protected] Volume Sub-Editors Neela Sarkar, Associate Professor, New Alipore College, W.B. Email: [email protected] Barnali Saha, Research Scholar, Guru Gobind Singh IP University, Delhi Email: [email protected] Editorial Board: Anil Raina, Professor of English, Panjab University Email: [email protected] Debarati Bandyopadhyay, Professor of English, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Email: [email protected] Himadri Lahiri, Professor of English, University of Burdwan Email: [email protected] Manju Jaidka, Professor, Shoolini University, Solan Email: [email protected] Rimika Singhvi, Associate Professor, IIS University, Jaipur Email: [email protected] Roshan Lal Sharma, Professor, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala Email: [email protected] 2 3 EDITORIAL NOTE MEJO, or the MELOW Journal of World Literature, is a peer-refereed E-journal brought out biannually by MELOW, the Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World. It is a reincarnation of the previous publications brought out in book or printed form by the Society right since its inception in 1998. MELOW is an academic organization, one of the foremost of its kind in India. -

Modern Art Auction

Modern Art July - 2021 LIVE AUCTION Modern Art 6th July, 2021 www.prinseps.com Curator's Note Prinseps is delighted to announce its summer modern art auction. We at Prinseps pride ourselves on being not just an auction house but a storehouse of knowledge. After in-depth research and analysis conducted by experts and constantly keeping an eye for sublime luxury, we present our summer auction. The history of modern Indian art is often riddled with gaps and holes. Documentation is rather inadequate and sources seldom reliable. We believe that we can change that.... we plunge into these unknown, unchartered, and fascinating depths to discover treasure troves. Our focus is to bring forward extraordinary works that have been hitherto ignored. Modern Art The 1940s were a defining chapter for modern art in the country, with Indian artists practically th blooming and blossoming ... experimenting with their individual style, expressing their creativity, 6 July, 2021 making socio-political statements that would go on to be etched in time forever. It was an explosion of home-grown talent. These path-breakers were the “Progressive Artists” of India. Our modern art auction is essentially composed of three distinguished estates. Over the years, Prinseps has managed to acquire the estates of some avant-garde personalities, the most recent Auction is now open for written bids / proxy bidding being the sole female member of the Progressive Artists' Group, Bhanu Athaiya. Live Auction commences at 7.00 pm on 6th July 2021 This auction offers to the discerning connoisseur a cornucopia of art that was lost in the sands Lots will be auctioned sequentially.