Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Sample Pages

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 51 F M" INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-J UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY c::<::s CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Cross-Cultural Readings of Chineseness Narratives, Images, and Interpretations of the 1990s EDITED BY Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cross-cultural readings of Chineseness : narratives, images, and interpretations of the 1990s I edited by Wen-hsin Yeh. p. em. - (China research monograph; 51) Collection of papers presented at the conference "Theoretical Issues in Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies". Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-55729-064-4 1. Chinese literature-20th century-History and criticism Congresses. 2. Arts, Chinese-20th century Congresses. 3. Motion picture-History and criticism Congresses. 4. Postmodernism-China Congresses. I. Yeh, Wen-hsin. -

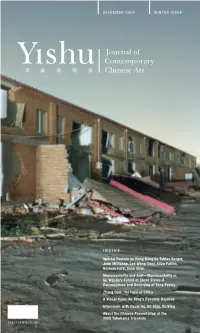

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

Chinese Avant-Garde Art: Body and Spirit Struggle for a New Cultural

ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2011 Chinese Avant-Garde Art: Body and Spirit Struggle for a New Cultural Identity Chie Lee The images in this paper are strictly for educational use and are protected by United States copyright laws. 1 Unauthorized use will result in criminal and civil penalties. ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2011 To understand the relationship between avant-garde art and cultural identity in China, a basic understanding of the historical and cultural contexts is essential. The Cultural Revolution in China did not begin after Mao took power in 1949—it began with the May 4th movement of 1919. After suffering a series of deep national humiliations by the West, the revolution to break down the old culture began. The movement, led by students and intellectuals, proclaimed that if China was to survive in the 20th century with any integrity as a country, the Confucian traditional values had to be rejected. China must openly adopt Western political, economic, and social values in order to modernize and bring about a new China. This was the beginning of the quest for a new cultural and political identity. Some forty some years later, Mao’s Cultural Revolution, which began in the 1960s, took the May 4th movement to its extreme. The Red Guards, most of them teenagers, were unleashed onto the populace and carried out the central propaganda edict of “smashing the Four Olds”: old habits, old customs, old culture and old ideas. Mao’s Cultural Revolution was catastrophic in the indiscriminate destruction of lives, property, and all manifestations of art and culture. -

The Political Body in Chinese Art

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 1-1-2011 The olitP ical Body in Chinese Art Curtis Carter Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted Version. "The oP litical Body in Chinese Art" in Subversive Strategies in Contemporary Chinese Art. Eds. Mary Bittner Wiseman and Yuedi Liu. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2011: 109-125. DOI: DOI. © 2011 Brill. Used with permission. NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page. The Political Body in Chinese Art Curtis L. Carter Department of Philosophy, Marquette University Milwaukee, WI The uses of visual images based on calligraphy and the depiction of the human body in Chinese art have served an important role in the exercise of political power by leaders in Chinese culture. The two media that are most closely linked to the exercise of political power in Chinese culture are written or performed calligraphy and representational art featuring the human figure. The latter is more familiar in western nations where one often finds sculptures of political figures displayed in prominent public spaces. However, in China calligraphy as a form of written art serves as a principal symbolic expression of political power. This is true in both traditional Chinese culture and also the Twentieth Century revolutionary period and beyond. The connection between figurative political images and political power needs little explanation for a western audience. But how is calligraphy connected to the theme of the political body in Chinese art and culture? One answer is offered in Mao Zedong’s early writings, where he linked the practice of calligraphy to physical training of the body. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

![[Brand × Artist] Collaborations](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2226/brand-%C3%97-artist-collaborations-662226.webp)

[Brand × Artist] Collaborations

FROM HIGH ART TO HIGH TOPS : THE IMPACT OF [ BRAND × ARTIST ] COLLABORATIONS WORD S A NYA FIRESTO N E On the world-map of today’s creative brands, we increasingly find Margiela. That art is being called upon as branding’s new muse, and collaborations with art — contemporary or otherwise — where × signifies a drive to create something more complex than that which marks the spot: can be achieved through fashion. It is logical that this nouveau artistic collaborative wave hits hard Don Perignon × Jeff Koons today, an epoch when magic is no longer required to see almost Perrier × Andy Warhol anything and everything thanks to the world’s new beloved fairy Supreme × Damien Hirst godmother: #socialmedia. With the advent of digital platforms comes Raf Simons × Sterling Ruby the collective impulse to display not only a style, but perhaps more COMME des GARÇONS × Ai Weiwei importantly, lifestyle. Look at any creative company’s Instagram and Lacoste × Zaha Hadid we find not only pictures of its gadgets and gizmos, but a cultivated Opening Ceremony × René Magritte existence around them — tastes and sensibilities, filtered through adidas × Jeremy Scott “Keith Harring” specific lenses: urban landscapes, graffiti, perfectly frothed lattes, Pharell’s hat, Kanye’s pout, and various other facades of society And so the formula of [Brand by Artist] is written, etched onto that visually amalgamate to project a brand’s metaphysical culture skateboards and sneakers, from H&M to Hermés, on Perignon to in time and space. Perrier, strutting down catwalks and stacking grocery aisles at a prolific It is no wonder then why brands are increasingly seduced by art; rate. -

Impeded Language in EE Cummings' Poetry and Xu

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1995 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky Anna Neher Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Neher, Anna, "Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky" (1995). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 262. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/262 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY An equal opportunity university Honors■ Program HONORS THESIS In presenting this Honors paper in partial requirements for a bachelor ’s degree at Western Washington University, 1 agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood that any publication of this thesis for commercial purposes or for financial 2 ain shall not be allowed without mv written permission. Signature Date G- Anna Neher 1 Anna Neher Dr. Melissa Walt Honors Senior Project June 10, 2005 Extraordinary Language: Impeded Language in E.E. Cummings’ Poetry and Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky ”In the twentieth century as never before, form calls attention to itself.. -

PICASSO: Mosqueteros

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y February 14, 2009 PRESS RELEASE GAGOSIAN GALLERY 522 WEST 21ST STREET T. 212.741.1717 NEW YORK, NY 10011 F. 212.741.0006 GALLERY HOURS: Mon – Sat: 10:00am– 6:00pm PICASSO: Mosqueteros Thursday, March 26 – Saturday, June 6, 2009 Opening reception: Thursday, March 26th, from 6 to 8pm I enjoy myself to no end inventing these stories. I spend hour after hour while I draw, observing my creatures and thinking about the mad things they're up to. --Pablo Picasso, 1968 “Picasso: Mosqueteros” is the first exhibition in the United States to focus on the late paintings since “Picasso: The Last Years: 1963-1973” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1984. Organized around a large group of important, rarely seen works from the collection of Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, as well as works from The Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museo Picasso Málaga and other private collections, “Picasso: Mosqueteros” aims to expand the ongoing inquiry regarding the context, subjects, and sources of the artist’s late work. Building on new research into the artist’s late life through the presentation of selected paintings and prints spanning 1962-1972, the exhibition suggests how the portrayal of the aged Picasso, bound to the past in his life and painting, has obscured the highly innovative and contemporary nature of the late work. The tertulia, an Iberian tradition of gregarious social gatherings with literary or artistic overtones, played a major part in Picasso’s everyday life, even after he moved to the relative seclusion of Notre-Dame-de-Vie in the 1960s. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

Jeff Koons Loses French Lawsuit Over ‘Slavish Copy’ of Naf Naf Advert US Artist Ordered to Pay Damages and Costs, but Fair D’Hiver Sculpture Escapes Seizure

AiA Art News-service Jeff Koons loses French lawsuit over ‘slavish copy’ of Naf Naf advert US artist ordered to pay damages and costs, but Fair d’Hiver sculpture escapes seizure ANNA SANSOM 9th November 2018 13:58 GMT Fait D'Hiver (1988) by Jeff Koons, on show at the Liebighaus museum on in Frankfurt in 2012 © Ralph Orlowski/Getty Images Jeff Koons has been found guilty of plagiarising a 1980s advertising campaign for French fashion brand Naf Naf to make his porcelain sculpture Fait d'Hiver (1988), which is part of his Banality series. The high court of Paris has ordered the artist’s company Jeff Koons LLC, and the Centre Pompidou, which exhibited the piece in a 2014 Koons exhibition, to pay Franck Davidovici, the creative director of Naf Naf, €135,000 in damages and interest, and €70,000 in trial costs. The court ruled that Jeff Koons LLC had counterfeited a 1985 Naf Naf advert, featuring a pig with a barrel of rum tied round its neck rescuing a girl in the snow, by using its “original elements”. Davidovici had sued for copyright infringement, with his lawyer, Jean Aittouares of Ox Avocats, describing the Koons sculpture as a “slavish copy” of the advert. “The court dismisses the argument of freedom of artistic expression, considering that Koons had clearly sought, by retaking the first work, to make 'the economy of a creative work',” Ox Avocats posted in a short online statement. The court also ordered Koons' company to pay €11,000 to Davidovici for reproducing an image of the sculpture on Koons' website, and €2,000 to Flammarion, the French publishing house, for reproducing an image of the work in the Centre Pompidou's exhibition catalogue. -

2/503 Photo of the Month ~

October 2012, Issue 46 Contact: [email protected] See all issues to date at the 503rd Heritage Battalion website: http://corregidor.org/VN2-503/newsletter/issue_index.htm _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ~ 2/503 Photo of the Month ~ The Aftermath C/2/503 troopers taking care of their buddies, circa ’66/’67. Photo by Jack Leide, CO C/2/503d. 2/503d VIETNAM Newsletter / October 2012 – Issue 46 Page 1 of 60 Boats could not be used and a helicopter was called, but Chaplain’s Corner its chance of success was not good, as the whipping snowstorm would be risky, just as it was when it brought the airplane down. Nevertheless, twenty minutes after He Died For Us the crash and as the sun was going down a rescue chopper came. One victim was hoisted out, and then as Once more into the battle…it was St. the cable was lowered again something miraculous Crispen’s Day - the year 1415. We’re happened. The man who grabbed it, passed it on to in France near Agincourt. The two “Cap” another who was hauled out. Again the cable was enemies, France and England, face one lowered and the man passed it on to another who was another, and exchanging taunts designed to provoke an lifted out. Again the same thing happened. As the attack. King Henry marches his force close enough to chopper seconds later wheeled to again drop the cable, allow his archers to unleash a hail of arrows upon the the man had vanished beneath the icy water. Who was French. The French knights charged forward only to be he? Arland Dean Williams, Jr. -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona.