0Ca60ed30ebe5571e9c604b661

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Sample Pages

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 51 F M" INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-J UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY c::<::s CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Cross-Cultural Readings of Chineseness Narratives, Images, and Interpretations of the 1990s EDITED BY Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cross-cultural readings of Chineseness : narratives, images, and interpretations of the 1990s I edited by Wen-hsin Yeh. p. em. - (China research monograph; 51) Collection of papers presented at the conference "Theoretical Issues in Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies". Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-55729-064-4 1. Chinese literature-20th century-History and criticism Congresses. 2. Arts, Chinese-20th century Congresses. 3. Motion picture-History and criticism Congresses. 4. Postmodernism-China Congresses. I. Yeh, Wen-hsin. -

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

University of California, San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Comparative Literature by Xiangyang Liu Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Wai-lim Yip 2010 The Thesis of Xiangyang Liu is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents…………….…………………………………………………...… iv Abstract………………………………………………………………..…................ v Introduction…………………………………………………………… …………... 1 Chapter One A Modern City in the Perspective of Two Generations……………………………... 3 Chapter Two Urban Culture: Transmission and circling………………………………………….. 27 Chapter Three Negotiation with Shanghai’s Present and Past…………………………………….... 51 Conclusion………………………...………………………………………………… 86 Bibliography..……………………..…………………………………………… …….. 90 iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film by Xiangyang Liu Master of Arts in Comparative Literature University of California, San Diego, 2010 Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair This thesis is intended to investigate a series of films produced since the 1990s. All of these films deal with -

Ancient Allure Seen Through a Screen

22 | Thursday, July 25, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY LIFE Ancient allure seen through a screen The popularity of a recent online Popular tour sites drama staged in Top scenic areas in Xi’an in the Tang Dynasty summer 1. Emperor Qinshihuang’s has translated into Mausoleum Site Museum a surge of visitors 2. Xi’an City Walls 3. Tang Paradise Theme Park to Xi’an, 4. Shaanxi History Museum 5. Muslim Street Xu Lin reports. 6. Huaqing Palace 7. North Square of Giant Wild he hit thriller series, The Goose Pagoda Longest Day in Chang’an, 8. Daming Palace National takes viewers to the heyday Heritage Park of the Tang Dynasty (618 9. Yongxing Fang T907). And since its premiere on June 10. Sleepless City of Tang 27, it has been creating a new heyday for Xi’an’s travel sector and interest SOURCE: MAFENGWO in its past. In the online drama, a deathrow Top domestic filming spots as inmate, played by actor Lei Jiayin, summer destinations accepts a mission from a govern 1. Xi’an, Shaanxi province ment official, played by singeractor 2. Suzhou, Jiangsu province Yi Yangqianxi, during Lantern Festi 3. Chongqing val. The condemned criminal must 4. Zhangjiajie, Hunan province save the national capital, Chang’an, 5. Nanjing, Jiangsu province from a secret enemy attack within 24 6. Shanghai hours. Chang’an is today Shaanxi’s 7. Qingdao, Shandong province provincial capital, Xi’an. 8. Dongyang, Zhejiang province The show’s extreme popularity 9. Bayanbulak Grassland, Xinji has intensified interest in travel to ang Uygur autonomous region Xi’an. -

New China's Forgotten Cinema, 1949–1966

NEW CHINA’S FORGOTTEN CINEMA, 1949–1966 More Than Just Politics by Greg Lewis Several years ago when planning a course on modern Chinese history as seen through its cinema, I realized or saw a significant void. I hoped to represent each era of Chinese cinema from the Leftist movement of the 1930s to the present “Sixth Generation,” but found most available subtitled films are from the post-1978 reform period. Films from the Mao Zedong period (1949–76) are particularly scarce in the West due to Cold War politics, including a trade embargo and economic blockade lasting more than two decades, and within the arts, a resistance in the West to Soviet- influenced Socialist Realism. wo years ago I began a project, Translating New China’s Cine- Phase One. Economic Recovery, ma for English-Speaking Audiences, to bring Maoist Heroic Revolutionaries, and Workers, T cinema to students and educators in the US. Several genres Peasants, and Soldiers (1949–52) from this era’s cinema are represented in the fifteen films we have Despite differences in perspective on Maoist cinema, general agree- subtitled to date, including those of heroic revolutionaries (geming ment exists as to the demarcation of its five distinctive phases (four yingxiong), workers-peasants-soldiers (gongnongbing), minority of which are represented in our program). The initial phase of eco- peoples (shaoshu minzu), thrillers (jingxian), a children’s film, and nomic recovery (1949–52) began with the emergence of the Dong- several love stories. Collectively, these films may surprise teachers bei (later Changchun) Film Studio as China’s new film capital. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Part 1: a Brief History of the Chinese Film Industry 1896 –A Film by The

Part 1: A brief History of the Chinese Film Industry 1896 –a film by the Lumiere Brothers, premiered in Paris in December 1895, was shown in Shanghai 1897 – American showman James Ricalton showed several Edison films in Shanghai and other large cities in China. This new media was introduced as “Western shadow plays” to link to the long- standing Chinese tradition of shadow plays. These early films were shown as acts as part of variety shows. 1905 – Ren Jingfeng, owner of Fengtai Photography, bought film equipment from a German store in Beijing and made a first attempt at film production. The film “Dingjun Mountain” featured episodes from a popular Beijing opera play. The screening of this play was very successful and Ren was encouraged to make more films based on Beijing opera. Subsequently, the base of Chinese film making became the port of Shanghai because of better access to foreign capital, imported materials and technical cooperation between the Chinese and foreigners. 1907 – Beijing had the first theatre devoted exclusively to showing films 1908 – Shanghai had its first film theatre 1909 – The Asia Film Company was established as a joint venture between American businessman, Benjamin Polaski, and Zhang Shichuan and Zheng Zhengqui. Zhang and Zheng are honoured as the fathers of Chinese cinema 1913 – Zhang and Zheng made the first Chinese short feature film, which was a documentary of social customs. As female performers were not allowed to share the stage with males, all the characters were played by male performers in this narrative drama. 1913 – saw the first narrative film produced in Hong Kong WW1 cut off Shanghai’s supply of raw film from Germany, so film production stopped. -

07Cmyblookinside.Pdf

2007 China Media Yearbook & Directory WELCOMING MESSAGE ongratulations on your purchase of the CMM- foreign policy goal of China’s media regulators is to I 2007 China Media Yearbook & Directory, export Chinese culture via TV and radio shows, films, Cthe most comprehensive English resource for books and other cultural products. But, of equal im- businesses active in the world’s fastest growing, and portance, is the active regulation and limitation of for- most complicated, market. eign media influence inside China. The 2007 edition features the same triple volume com- Although the door is now firmly shut on the establish- bination of CMM-I independent analysis of major de- ment of Sino-foreign joint venture TV production com- velopments, authoritative industrial trend data and panies, foreign content players are finding many other fully updated profiles of China’s major media players, opportunities to actively engage with the market. but the market described has once again shifted fun- damentally on the inside over the last year. Of prime importance is the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympiad. At no other time in Chinese history have so Most basically, the Chinese economic miracle contin- many foreign media organizations engaged in co- ued with GDP growth topping 10 percent over 2005-06 production features exploring the modern as well as and, once again, parts of China’s huge and diverse old China. But while China has relaxed its reporting media industry continued to expand even faster over procedures for the duration, it would be naïve to be- the last twelve months. lieve this signals any kind of fundamental change in the government’s position. -

The Rise and Fall of the Wolf Warriors

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WOLF WARRIORS Yun Jiang N 2020, the usually polite and us ‘chequebook diplomacy’ (aid Iconservative diplomats from the and investment to gain diplomatic People’s Republic of China (PRC) recognition vis-à-vis Taiwan) and attracted attention around the world ‘panda diplomacy’ (sending pandas to for breaking form. ‘Wolf warrior build goodwill). diplomacy’ is a term used to describe Wolf Warrior 战狼 was a popular the newly assertive and combative Chinese film released in 2015. It was style of Chinese diplomats, in action followed by a sequel, Wolf Warrior 2, as well as rhetoric. It is not the only which became the highest-grossing diplomacy-related term that China film in Chinese box office history. They became famous for this year; there were both aggressively nationalistic was also ‘mask diplomacy’ (the films, comparable with Hollywood’s shipment of medical goods to build Rambo, portraying the Chinese hero goodwill) and ‘hostage diplomacy’ as someone who saves his compatriots (the detention of foreign citizens in and others from international China to gain leverage over another ‘bad guys’, including American country). Previous years brought mercenaries. The tagline of both films 34 powerful counter-attack only when 35 being attacked’ is more like Kung Fu Panda, while wolf warrior diplomacy is more of a ‘US trait’.1 However it is characterised, the way Chinese diplomats operate reflects the attitude to diplomacy and foreign affairs of the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The discretionary The Rise and Fall of the Wolf Warriors The Rise and Fall of the Wolf Yun Jiang power of even the top foreign policy bureaucrats and diplomats is relatively CRISIS limited in the Chinese system. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

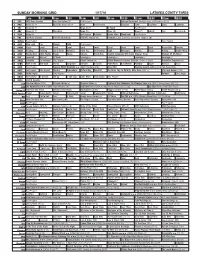

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

Titolo Anno Paese

compensi "copia privata" per l'anno 2018 (*) Per i film esteri usciti in Italia l’anno corrisponde all’anno di importazione titolo anno paese #SCRIVIMI ANCORA (LOVE, ROSIE) 2014 GERMANIA '71 2015 GRAN BRETAGNA (S) EX LIST ((S) LISTA PRECEDENTE) (WHAT'S YOUR NUMBER?) 2011 USA 002 OPERAZIONE LUNA 1965 ITALIA/SPAGNA 007 - IL MONDO NON BASTA (THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH) 2000 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 BERSAGLIO MOBILE (A VIEW TO A KILL) 1985 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 DOMANI NON MUORE MAI (IL) (TOMORROW NEVER DIES) 1997 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 SOLO PER I TUOI OCCHI (FOR YOUR EYES ONLY) 1981 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 VENDETTA PRIVATA (LICENCE TO KILL) 1989 USA 007 ZONA PERICOLO (THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS) 1987 GRAN BRETAGNA 10 CLOVERFIELD LANE 2016 USA 10 REGOLE PER FARE INNAMORARE 2012 ITALIA 10 YEARS - (DI JAMIE LINDEN) 2011 USA 10.000 A.C. (10.000 B.C.) 2008 USA 10.000 DAYS - 10,000 DAYS (DI ERIC SMALL) 2014 USA 100 DEGREES BELOW ZERO - 100 GRADI SOTTO ZERO 2013 USA 100 METRI DAL PARADISO 2012 ITALIA 100 MILLION BC 2012 USA 100 STREETS (DI JIM O'HANLON) 2016 GRAN BRETAGNA 1000 DOLLARI SUL NERO 1966 ITALIA/GERMANIA OCC. 11 DONNE A PARIGI (SOUS LES JUPES DES FILLES) 2015 FRANCIA 11 SETTEMBRE: SENZA SCAMPO - 9/11 (DI MARTIN GUIGUI) 2017 CANADA 11.6 - THE FRENCH JOB (DI PHILIPPE GODEAU) 2013 FRANCIA 110 E FRODE (STEALING HARVARD) 2003 USA 12 ANNI SCHIAVO (12 YEARS A SLAVE) 2014 USA 12 ROUND (12 ROUNDS) 2009 USA 12 ROUND: LOCKDOWN - (DI STEPHEN REYNOLDS) 2015 USA 120 BATTITI AL MINUTO (120 BETTEMENTS PAR MINUTE) 2017 FRANCIA 127 ORE (127 HOURS) 2011 USA 13 2012 USA 13 HOURS (13 HOURS: