Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Yimou Interviews Edited by Frances Gateward

ZHANG YIMOU INTERVIEWS EDITED BY FRANCES GATEWARD Discussing Red Sorghum JIAO XIONGPING/1988 Winning Winning Credit for My Grandpa Could you discuss how you chose the novel for Red Sorghum? I didn't know Mo Yan; I first read his novel, Red Sorghum, really liked it, and then gave him a phone call. Mo Yan suggested that we meet once. It was April and I was still filming Old Well, but I rushed to Shandong-I was tanned very dark then and went just wearing tattered clothes. I entered the courtyard early in the morning and shouted at the top of my voice, "Mo Yan! Mo Yan!" A door on the second floor suddenly opened and a head peered out: "Zhang Yimou?" I was dark then, having just come back from living in the countryside; Mo Yan took one look at me and immediately liked me-people have told me that he said Yimou wasn't too bad, that I was just like the work unit leader in his village. I later found out that this is his highest standard for judging people-when he says someone isn't too bad, that someone is just like this village work unit leader. Mo Yan's fiction exudes a supernatural quality "cobblestones are ice-cold, the air reeks of blood, and my grandma's voice reverberates over the sorghum fields." How was I to film this? There was no way I could shoot empty scenes of the sorghum fields, right? I said to Mo Yan, we can't skip any steps, so why don't you and Chen Jianyu first write a literary script. -

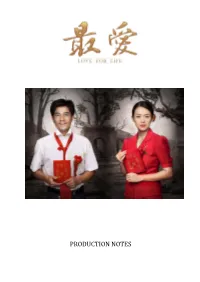

Zhang Ziyi and Aaron Kwok

PRODUCTION NOTES Set in a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, LOVE FOR LIFE is the story of De Yi and Qin Qin, two victims faced with the grim reality of impending death, who unexpectedly fall in love and risk everything to pursue a last chance at happiness before it’s too late. SYNOPSIS In a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, the Zhao’s are a family caught in the middle. Qi Quan is the savvy elder son who first lured neighbors to give blood with promises of fast money while Grandpa, desperate to make amends for the damage caused by his family, turns the local school into a home where he can care for the sick. Among the patients is his second son De Yi, who confronts impending death with anger and recklessness. At the school, De Yi meets the beautiful Qin Qin, the new wife of his cousin and a recent victim of the virus. Emotionally deserted by their respective spouses, De Yi and Qin Qin are drawn to each other by the shared disappointment and fear of their fate. With nothing to look forward to, De Yi capriciously suggests becoming lovers but as they begin their secret affair, they are unprepared for the real love that grows between them. De Yi and Qin Qin’s dream of being together as man and wife, to love each other legitimately and freely, is jeopardized when the villagers discover their adultery. With their time slipping away, they must decide if they will surrender everything to pursue one chance at happiness before it’s too late. -

Yuan Muzhi Y La Comedia Modernista De Shanghai

Yuan Muzhi y la comedia modernista de Shanghai Ricard Planas Penadés ------------------------------------------------------------------ TESIS DOCTORAL UPF / Año 2019 Director de tesis Dr. Manel Ollé Rodríguez Departamento de Humanidades Als meus pares, en Francesc i la Fina. A la meva companya, Zhang Yajing. Per la seva ajuda i comprensió. AGRADECIMIENTOS Quisiera dar mis agradecimientos al Dr. Manel Ollé. Su apoyo en todo momento ha sido crucial para llevar a cabo esta tesis doctoral. Del mismo modo, a mis padres, Francesc y Fina y a mi esposa, Zhang Yajing, por su comprensión y logística. Ellos han hecho que los días tuvieran más de veinticuatro horas. Igualmente, a mi hermano Roger, que ha solventado más de una duda técnica en clave informática. Y como no, a mi hijo, Eric, que ha sido un gran obstáculo a la hora de redactar este trabajo, pero también la mayor motivación. Un especial reconocimiento a Zheng Liuyi, mi contacto en Beijing. Fue mi ángel de la guarda cuando viví en aquella ciudad y siempre que charlamos me ofrece una versión interesante sobre la actualidad académica china. Por otro lado, agradecer al grupo de los “Aspasians” aquellos descansos entra página y página, aquellos menús que hicieron más llevadero el trabajo solitario de investigación y redacción: Xavier Ortells, Roberto Figliulo, Manuel Pavón, Rafa Caro y Sergio Sánchez. v RESUMEN En esta tesis se analizará la obra de Yuan Muzhi, especialmente los filmes que dirigió, su debut, Scenes of City Life (都市風光,1935) y su segunda y última obra Street Angel ( 马路天使, 1937). Para ello se propone el concepto comedia modernista de Shanghai, como una perspectiva alternativa a las que se han mantenido tanto en la academia china como en la anglosajona. -

New China's Forgotten Cinema, 1949–1966

NEW CHINA’S FORGOTTEN CINEMA, 1949–1966 More Than Just Politics by Greg Lewis Several years ago when planning a course on modern Chinese history as seen through its cinema, I realized or saw a significant void. I hoped to represent each era of Chinese cinema from the Leftist movement of the 1930s to the present “Sixth Generation,” but found most available subtitled films are from the post-1978 reform period. Films from the Mao Zedong period (1949–76) are particularly scarce in the West due to Cold War politics, including a trade embargo and economic blockade lasting more than two decades, and within the arts, a resistance in the West to Soviet- influenced Socialist Realism. wo years ago I began a project, Translating New China’s Cine- Phase One. Economic Recovery, ma for English-Speaking Audiences, to bring Maoist Heroic Revolutionaries, and Workers, T cinema to students and educators in the US. Several genres Peasants, and Soldiers (1949–52) from this era’s cinema are represented in the fifteen films we have Despite differences in perspective on Maoist cinema, general agree- subtitled to date, including those of heroic revolutionaries (geming ment exists as to the demarcation of its five distinctive phases (four yingxiong), workers-peasants-soldiers (gongnongbing), minority of which are represented in our program). The initial phase of eco- peoples (shaoshu minzu), thrillers (jingxian), a children’s film, and nomic recovery (1949–52) began with the emergence of the Dong- several love stories. Collectively, these films may surprise teachers bei (later Changchun) Film Studio as China’s new film capital. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Major Retailers Celebrate Lunar New Year • the Lunar New Year, the Year of the Monkey, Starts Today, February 8, 2016

FEB. 08, 2016 Major Retailers Celebrate Lunar New Year • The Lunar New Year, the Year of the Monkey, starts today, February 8, 2016. • Major retailers and international brands are courting Asian consumers, launching special Chinese New Year promotions, window displays, limited- edition products, and themed entertainment and other unique activities. • In 2015, Chinese consumers’ overseas luxury purchases grew by 10% year over year and shopping tourism from China increased by 32%, according to Bain & Company. • Last year, Chinese shoppers bought 78% of their high-end purchases outside Mainland China, according to the China-based Fortune Character Institute. The 2016 Lunar New Year, wHicH starts on February 8, will be celebrated across tHe globe by more tHan a billion people, making it one of tHe world’s biggest Holidays. According to the Chinese zodiac, 2016 is tHe Year of tHe Monkey. China has declared a national holiday this year that runs February 7–13, wHicH paves tHe way for tHe massive travel tHat accompanies the 40-day Chunyun period. During tHis Spring Festival travel period eacH year, the largest Human migration in the world takes place; in 2015, travelers made more tHan 3.7 billion trips during the 40 days. HigHligHts of tHe Holiday include traveling Home to be with family, family reunion dinners, parades, fireworks, dancing and tHe gifting of hongbao—red envelopes filled with cash and given by married people to cHildren, unmarried relatives, friends and employees. MAJOR RETAILERS AND INTERNATIONAL BRANDS COURT ASIAN CONSUMERS In recent years, major retailers and international brands have been courting Asian consumers, Hoping to become tHe shopping destination of choice for New Year’s gifts. -

Part 1: a Brief History of the Chinese Film Industry 1896 –A Film by The

Part 1: A brief History of the Chinese Film Industry 1896 –a film by the Lumiere Brothers, premiered in Paris in December 1895, was shown in Shanghai 1897 – American showman James Ricalton showed several Edison films in Shanghai and other large cities in China. This new media was introduced as “Western shadow plays” to link to the long- standing Chinese tradition of shadow plays. These early films were shown as acts as part of variety shows. 1905 – Ren Jingfeng, owner of Fengtai Photography, bought film equipment from a German store in Beijing and made a first attempt at film production. The film “Dingjun Mountain” featured episodes from a popular Beijing opera play. The screening of this play was very successful and Ren was encouraged to make more films based on Beijing opera. Subsequently, the base of Chinese film making became the port of Shanghai because of better access to foreign capital, imported materials and technical cooperation between the Chinese and foreigners. 1907 – Beijing had the first theatre devoted exclusively to showing films 1908 – Shanghai had its first film theatre 1909 – The Asia Film Company was established as a joint venture between American businessman, Benjamin Polaski, and Zhang Shichuan and Zheng Zhengqui. Zhang and Zheng are honoured as the fathers of Chinese cinema 1913 – Zhang and Zheng made the first Chinese short feature film, which was a documentary of social customs. As female performers were not allowed to share the stage with males, all the characters were played by male performers in this narrative drama. 1913 – saw the first narrative film produced in Hong Kong WW1 cut off Shanghai’s supply of raw film from Germany, so film production stopped. -

China's Igeneration Cinema: Dispersion, Individualization And

Wagner, Keith B., Tianqi Yu, and Luke Vulpiani. "China’s iGeneration Cinema: Dispersion, Individualization and Post-WTO Moving Image Practices." China’s iGeneration: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu and Luke Vulpiani. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 1–20. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501300103.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 08:45 UTC. Copyright © Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu, Luke Vulpiani and Contributors 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Introduction China’s iGeneration Cinema: Dispersion, Individualization and Post-WTO Moving Image Practices Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu with Luke Vulpiani Chinese cinema is moving beyond the theatrical screen. While the country is now the world’s second-largest film market in addition to being the world’s second-largest economy, visual culture in China is increasingly multi-platform and post-cinematic.1 Digital technology, network-based media and portable media player platforms have contributed to the creation of China’s new cinema of dispersion or ‘iGeneration cinema,’ which is oriented as much toward individual, self-directed viewers as toward traditional distribution channels such as the box office, festival, or public spaces. Visual culture in China is no longer dominated by the technology and allure of the big screen, if indeed it ever was. While China’s film industry still produces ‘traditional’ box-office blockbusters and festival-ready documentaries, their impact and influence is increasingly debatable. -

Tibet in Debate: Narrative Construction and Misrepresentations in Seven Years in Tibet and Red River Valley

Transtext(e)s Transcultures 跨文本跨文化 Journal of Global Cultural Studies 5 | 2009 Varia Tibet in Debate: Narrative Construction and Misrepresentations in Seven Years in Tibet and Red River Valley Vanessa Frangville Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transtexts/289 DOI: 10.4000/transtexts.289 ISSN: 2105-2549 Publisher Gregory B. Lee Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2009 ISSN: 1771-2084 Electronic reference Vanessa Frangville, “Tibet in Debate: Narrative Construction and Misrepresentations in Seven Years in Tibet and Red River Valley”, Transtext(e)s Transcultures 跨文本跨文化 [Online], 5 | 2009, document 6, Online since 22 April 2010, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ transtexts/289 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/transtexts.289 © Tous droits réservés Journal of Global Cultural Studies 5 | 2009 : Varia (Re)Inventing "Realities" in China Tibet in Debate: Narrative Construction and Misrepresentations in Seven Years in Tibet and Red River Valley VANESSA FRANGVI E Résumés Cet article propose une analyse comparative de la construction des discours sur le Tibet et les Tib'tains en ( Occident * et en Chine. Il sugg.re /ue les films de propagande chinois comme les films holly0oodiens pro1tib'tains mettent en place des perceptions orientalistes et essentialistes d2un Tibet imagin' et id'alis', omettant ainsi la situation sociale, politi/ue, 'conomi/ue ou m4me 'cologi/ue telle /u2elle est v'cue par les Tib'tains en Chine. es repr'sentations cin'matographi/ues participant grandement 5 la formation des imaginaires modernes, cette analyse illustre ainsi le fait /ue la /uestion du Tibet n2est pas un vrai d'bat mais bien plus un champ de bataille politi/ue /ui m.ne 5 une impasse internationale et locale. -

A World Without Thieves: Film Magic and Utopian Fantasies

A World without Thieves: Film Magic and Utopian Fantasies Rujie Wang, College of Wooster Should we get serious about A World without Thieves (tian xia wu zei), with two highly skilled pickpockets, Wang Bo (played by Liu Dehua) and Wang Li (Liu Ruoying), risking their lives to protect both the innocence and the hard-earned money of an orphan and idiot who does not believe there are thieves in the world? The answer is yes, not because this film is a success in the popular entertainment industry but in spite of it. To Feng Xiaogang’s credit, the film allows the viewer to feel the pulse of contemporary Chinese cultural life and to express a deep anxiety about modernization. In other words, this production by Feng Xiaogang to ring in the year of the roster merits our critical attention because of its function as art to compensate for the harsh reality of a capitalist market economy driven by money, profit, greed, and individual entrepreneurial spirit, things of little value in the old ethical and religious traditions. The title is almost sinisterly ironic, considering the national problem of corruption and crime that often threatens to derail economic reform in China, although it may ring true for those optimists clinging tenaciously to the old moral ideals, from Confucians to communists, who have always cherished the utopia of a world without thieves. Even during the communist revolutions that redistributed wealth and property by violence and coercion, that utopian fantasy was never out of favor or discouraged; during the Cultural Revolution, people invented and bought whole-heartedly into the myth of Lei Feng (directed by Dong Yaoqi, 1963), a selfless PLA soldier and a paragon of socialist virtues, who wears socks with holes but manages to donate all his savings to the flood victims in a people’s commune. -

Alai and I: a Belated Encounter

Alai and I: A Belated Encounter Patrizia Liberati (Italian Institute of Culture) Abstract: This paper attempts to analyze the reasons for the scanty presence in translation of Alai’s literary production. Probably the most important motive is that this author’s narrative does not correspond to the idealized Western idea of Tibet as Shangri-la, and of its people as noble savages. It will then make some observation on Alai’s pictorial “thangka style” of narration, his unique use of language and his poetic realism. Finally, it will identify cinematic productions as a successful medium to spread knowledge and deepen the understanding of contemporary Tibetan literature. Keywords: cultural misreading, inter-religious studies, poetic realism, Shangri-la, stereotypes, thangka, transcultural contact, visual culture. 1. A Western Collective Delusion: Alai’s Tibet is Not Shangri-la In November 2018, the Sichuan Writers Association invited me to the symposium “Borderline Books, Naturalis Historia and Epics”, an international occasion to study Alai’s works. This presented me with the long overdue occasion to reflect on the writer’s literary creation. I soon realized that the number of Alai’s works in translation—at least in the Western languages I am able to understand—compares very badly with the abundancy and richness of his creation. I found English, French and Italian translations of Cheng’ai luoding and English translations of Gesair Wang and Kong Shan. There are some short stories like Wind over the Grasslands; Three Grassworms; Aku Tonpa; The Hydroelectric Station and The Threshing Machine in English. Now I am pleased to add to the list the translation in Italian of Yueguang xia de yinjiang (L’argentiere sotto la luna, tr. -

The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: an Analysis of The

THE CURIOUS CASE OF CHINESE FILM CENSORSHIP: AN ANALYSIS OF THE FILM ADMINISTRATION REGULATIONS by SHUO XU A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Shuo Xu Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Gabriela Martínez Chairperson Chris Chávez Member Daniel Steinhart Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2017 ii © 2017 Shuo Xu iii THESIS ABSTRACT Shuo Xu Master of Arts School of Journalism and Communication December 2017 Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations The commercialization and global transformation of the Chinese film industry demonstrates that this industry has been experiencing drastic changes within the new social and economic environment of China in which film has become a commodity generating high revenues. However, the Chinese government still exerts control over the industry which is perceived as an ideological tool. They believe that the films display and contain beliefs and values of certain social groups as well as external constraints of politics, economy, culture, and ideology. This study will look at how such films are banned by the Chinese film censorship system through analyzing their essential cinematic elements, including narrative, filming, editing, sound, color, and sponsor and publisher.