University of California, San Diego

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Sample Pages

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 51 F M" INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-J UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY c::<::s CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Cross-Cultural Readings of Chineseness Narratives, Images, and Interpretations of the 1990s EDITED BY Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cross-cultural readings of Chineseness : narratives, images, and interpretations of the 1990s I edited by Wen-hsin Yeh. p. em. - (China research monograph; 51) Collection of papers presented at the conference "Theoretical Issues in Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies". Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-55729-064-4 1. Chinese literature-20th century-History and criticism Congresses. 2. Arts, Chinese-20th century Congresses. 3. Motion picture-History and criticism Congresses. 4. Postmodernism-China Congresses. I. Yeh, Wen-hsin. -

Cheung, Leslie (1956-2003) by Linda Rapp

Cheung, Leslie (1956-2003) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2003, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Leslie Cheung first gained legions of fans in Asia as a pop singer. He went on to a successful career as an actor, appearing in sixty films, including the award-winning Farewell My Concubine. Androgynously handsome, he sometimes played sexually ambiguous characters, as well as romantic leads in both gay- and heterosexually-themed films. Leslie Cheung, born Cheung Kwok-wing on September 12, 1956, was the tenth and youngest child of a Hong Kong tailor whose clients included Alfred Hitchcock and William Holden. At the age of twelve Cheung was sent to boarding school in England. While there he adopted the English name Leslie, in part because he admired Leslie Howard and Gone with the Wind, but also because the name is "very unisex." Cheung studied textiles at Leeds University, but when he returned to Hong Kong, he did not go into his father's profession. He entered a music talent contest on a Hong Kong television station and took second prize with his rendition of Don McLean's American Pie. His appearance in the contest led to acting roles in soap operas and drama series, and also launched his singing career. After issuing two poorly received albums, Day Dreamin' (1977) and Lover's Arrow (1979), Cheung hit it big with The Wind Blows On (1983), which was a bestseller in Asia and established him as a rising star in the "Cantopop" style. He would eventually make over twenty albums in Cantonese and Mandarin. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Wreckage, War, Woman. Fragments of a Female Self in Zhang Ailing's

e-ISSN 2385-3042 ISSN 1125-3789 Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale Vol. 56 – Giugno 2020 Wreckage, War, Woman. Fragments of a Female Self in Zhang Ailing’s Love In a Fallen City (倾城之恋) Alessandra Di Muzio Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia Abstract This article examines wreckage and war as key elements in Zhang Ailing’s novella Qing cheng zhi lian 倾城之恋 (Love in a Fallen City) exploring the strategies used by the female protagonist to engage on a nüxing 女性 ‘feminist’-oriented spatial quest for independence in a male-centered world. Analysed from a feminist perspective, these strategies emerge as potentially empowering and based on the idea of conflict/con- quest while dealing with man and romance, but they are also constantly threatened by the instability of history and by the lack of any true agency and gender-specific space for women in the 1940s Chinese society and culture. By analysing the floating/stability dichotomy and the spatial configurations of Shanghai and Hong Kong as described in the novella, the author argues Zhang Ailing’s depiction of Chinese women while dealing with history, society and the quest for self-affirmation is left in-between wreckage and survival, oppression and feminism, revealing her eccentric otherness as a woman and as a writer with respect to socially committed literature. Keywords Zhang Ailing. Love in a Fallen City. Wreckage. War. Feminist spatial quest. Summary 1 Introduction. An Ambivalent Form of Desolation. – 2 From Wreckage to Wreckage. – 3 Conflict and Conquest. Bai Liusu and Her ‘War’ for Life. – 4 Empty Fragments Floating. -

Zz027 Bd 45 Stanley Kwan 001-124 AK2.Indd

Statt eines Vorworts – eine Einordnung. Stanley Kwan und das Hongkong-Kino Wenn wir vom Hongkong-Kino sprechen, dann haben wir bestimmte Bilder im Kopf: auf der einen Seite Jacky Chan, Bruce Lee und John Woo, einsame Detektive im Kampf gegen das Böse, viel Filmblut und die Skyline der rasantesten Stadt des Universums im Hintergrund. Dem ge- genüber stehen die ruhigen Zeitlupenfahrten eines Wong Kar-wai, der, um es mit Gilles Deleuze zu sagen, seine Filme nicht mehr als Bewe- gungs-Bild, sondern als Zeit-Bild inszeniert: Ebenso träge wie präzise erfährt und erschwenkt und ertastet die Kamera Hotelzimmer, Leucht- reklamen, Jukeboxen und Kioske. Er dehnt Raum und Zeit, Aktion in- teressiert ihn nicht sonderlich, eher das Atmosphärische. Wong Kar-wai gehört zu einer Gruppe von Regisseuren, die zur New Wave oder auch Second Wave des Hongkong-Kinos zu zählen sind. Ihr gehören auch Stanley Kwan, Fruit Chan, Ann Hui, Patrick Tam und Tsui Hark an, deren Filme auf internationalen Festivals laufen und liefen. Im Westen sind ihre Filme in der Literatur kaum rezipiert worden – und das will der vorliegende Band ändern. Neben Wong Kar-wai ist Stanley Kwan einer der wichtigsten Vertreter der New Wave, jener Nouvelle Vague des Hongkong-Kinos, die ihren künstlerischen und politischen Anspruch aus den Wirren der 1980er und 1990er Jahre zieht, als klar wurde, dass die Kronkolonie im Jahr 1997 von Großbritannien an die Volksrepublik China zurückgehen würde. Beschäftigen wir uns deshalb kurz mit der historischen Dimension. China hatte den Status der Kolonie nie akzeptiert, sprach von Hong- kong immer als unter »britischer Verwaltung« stehend. -

Romantic Relationships and Urban Modernity in the Writings of Han Bangqing and Zhang Ailing

ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS AND URBAN MODERNITY IN THE WRITINGS OF HAN BANGQING AND ZHANG AILING By Andrew M. Kauffman Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Languages and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Hui (Faye) Xiao ________________________________ Keith McMahon ________________________________ Elaine Gerbert Date Defended: 05/10/2013 The Thesis Committee for Andrew M. Kauffman certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS AND URBAN MODERNITY IN THE WRITINGS OF HAN BANGQING AND ZHANG AILING ________________________________ Chairperson Hui (Faye) Xiao Date approved: 05/21/2013 ii ABSTRACT Despite the vast amount of research done by Chinese and Western scholars on the writings of Han Bangqing (1854-1894) and, particularly, Zhang Ailing (1920-1995), there has been relatively little scholarship focusing on the connections between these two authors and their views on romance and urban modernity. This thesis seeks to address this problem by first exploring the connections between these two prominent Shanghai authors on three levels - personal, historical/cultural, and literary - and then examining how they portray romance and urban modernity in some of their pieces. In addition to Zhang Ailing’s extensive translation work on Han Bangqing’s Sing-song Girls of Shanghai, translating it first into Mandarin Chinese from the Wu dialect and then into English, a central connection between these two authors is the preeminent position of Shanghai in their writings. This thesis examines the culture and history of Shanghai and how it affected both writers. -

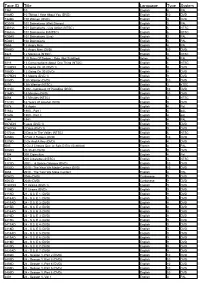

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films

Travelling Films: Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films Goldsmiths College University of London PhD thesis (Cultural Studies) Ji Yeon Lee Abstract This thesis analyses western criticism, labelling practices and the politics of European international film festivals. In particular, this thesis focuses on the impact of western criticism on East Asian films as they attempt to travel to the west and when they travel back to their home countries. This thesis draws on the critical arguments by Edward Said's Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient (1978) and self-Orientalism, as articulated by Rey Chow, which is developed upon Mary Louise Pratt's conceptual tools such as 'contact zone' and 'autoethnography'. This thesis deals with three East Asian directors: Kitano Takeshi (Japanese director), Zhang Yimou (Chinese director) and 1m Kwon-Taek (Korean director). Dealing with Japanese, Chinese and Korean cinema is designed to show different historical and cultural configurations in which each cinema draws western attention. This thesis also illuminates different ways each cinema is appropriated and articulated in the west. This thesis scrutinises how three directors from the region have responded to this Orientalist discourse and investigates the unequal power relationship that controls the international circulation of films. Each director's response largely depends on the particular national and historical contexts of each country and each national cinema. The processes that characterise films' travelling are interrelated: the western conception of Japanese, Chinese or Korean cinema draws upon western Orientalism, but is at the same time corroborated by directors' responses. Through self-Orientalism, these directors, as 'Orientals', participate in forming and confirming the premises of western Orientalism. -

{FREE} Love in a Fallen City Ebook Free Download

LOVE IN A FALLEN CITY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eileen Chang, Karen S. Kingsbury | 321 pages | 28 Dec 2006 | The New York Review of Books, Inc | 9781590171783 | English | New York, United States Love in a Fallen City by Eileen Chang: | : Books This is what Eileen tried to express: most marriages result from a variety of factors, love is only one of them. I can sense such kind of genteel manners as well as sadness but I do not know where they are from. In addition, I want to tell the truth that Eileen has now become one of the most popular writers in mainland China, even though the education department refuses to add her work in textbooks. I wish someone could tell her that her art work has illuminated this glooming world, even today. And lastly but not the least, may she find serenity and tranquility in another world. I strongly recommend you to read by Eileen. Eileen was fluent in both English and Chinese, and she wrote originally in English. This story is largely based on the real story of her own life, depicting and reflecting on the relationship between her mother and her. Hello Lucy, how lovely to meet you like this! I assume it is a Chinese concept? Can you please explain what it means, and why these critics thought it was important to include it in a work of fiction? By: Lisa Hill on August 26, at pm. By: Charlotte Verver on February 15, at pm. Ah, that makes sense. By: Lisa Hill on February 15, at pm. -

The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: an Analysis of The

THE CURIOUS CASE OF CHINESE FILM CENSORSHIP: AN ANALYSIS OF THE FILM ADMINISTRATION REGULATIONS by SHUO XU A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Shuo Xu Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Gabriela Martínez Chairperson Chris Chávez Member Daniel Steinhart Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2017 ii © 2017 Shuo Xu iii THESIS ABSTRACT Shuo Xu Master of Arts School of Journalism and Communication December 2017 Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations The commercialization and global transformation of the Chinese film industry demonstrates that this industry has been experiencing drastic changes within the new social and economic environment of China in which film has become a commodity generating high revenues. However, the Chinese government still exerts control over the industry which is perceived as an ideological tool. They believe that the films display and contain beliefs and values of certain social groups as well as external constraints of politics, economy, culture, and ideology. This study will look at how such films are banned by the Chinese film censorship system through analyzing their essential cinematic elements, including narrative, filming, editing, sound, color, and sponsor and publisher. -

0Ca60ed30ebe5571e9c604b661

Mark Parascandola ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI Cofounders: Taj Forer and Michael Itkoff Creative Director: Ursula Damm Copy Editors: Nancy Hubbard, Barbara Richard © 2019 Daylight Community Arts Foundation Photographs and text © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai and Notes on the Locations © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai: Images of a Film Industry in Transition © 2019 by Michael Berry All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-942084-74-7 Printed by OFSET YAPIMEVI, Istanbul No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of copyright holders and of the publisher. Daylight Books E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.daylightbooks.org 4 5 ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI: IMAGES OF A FILM INDUSTRY IN TRANSITION Michael Berry THE SOCIALIST PERIOD Once upon a time, the Chinese film industry was a state-run affair. From the late centers, even more screenings took place in auditoriums of various “work units,” 1940s well into the 1980s, Chinese cinema represented the epitome of “national as well as open air screenings in many rural areas. Admission was often free and cinema.” Films were produced by one of a handful of state-owned film studios— tickets were distributed to employees of various hospitals, factories, schools, and Changchun Film Studio, Beijing Film Studio, Shanghai Film Studio, Xi’an Film other work units. While these films were an important part of popular culture Studio, etc.—and the resulting films were dubbed in pitch-perfect Mandarin during the height of the socialist period, film was also a powerful tool for education Chinese, shot entirely on location in China by a local cast and crew, and produced and propaganda—in fact, one could argue that from 1949 (the founding of the almost exclusively for mainland Chinese film audiences.