Read the Article in PDF Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Contents Our Vision OUR VISION Is a Vibrant and Truly Pluralistic America, Where Muslims Are Strong and Equal LETTER from the DIRECTOR

Institute for Social Policy and Understanding Facts Are Fuel ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Contents Our vision OUR VISION is a vibrant and truly pluralistic America, where Muslims are strong and equal LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR ............. 3 participants. EIGHT WINS OF 2018 ......................... 4 WHAT WE DISCOVERED ....................... 5 ABED’S STORY ................................... 7 Our mission 2 HOW WE EDUCATED ............................ 8 ISPU CONDUCTS OBJECTIVE, solution-seeking research that empowers American Muslims to MATTHEW’S STORY ........................... 10 develop their community and fully contribute to democracy and pluralism in the United States. WHO WE ENABLED ............................ 11 CATHERINE’S STORY ..........................13 OUR FINANCIALS ...............................14 Our values YOUR SUPPORT .................................15 OUR TEAM .........................................16 COLLABORATIVE · ACTIONABLE · RIGOROUS RESPONSIVE · VISIONARY · EXCELLENT Dr. Zain Abdullah, Associate Professor of Religion at Temple University and a participant in our MAP NYC study / Photo by Syed Yaqeen Letter from the Director VER THE PAST nearly five years, I school administrators wishing to create and shares our research so our legal have had the privilege of leading safer and more inclusive classrooms. We system can become more just. The parent O ISPU and our team through a helped policymakers and government who advocates for their child to have a period of change, opportunity, growth, officials understand the impact of policies safe, inclusive environment at school. and vast expansion of our impact. It is on Muslim communities. your support that has made that possible. And who, ultimately, makes this work In a period of tumultuous change in We spearheaded the first Islamophobia possible? You. You empower us to work 3 America, you have provided facts that Index, empowering advocates and toward an America where our friends fuel positive change through your support interfaith bridge builders. -

Annual Administrative Report 2010-11. West Bengal.Pdf

Dr. Upendra Nath Biswas Minister-in-Charge, Backward Classes Welfare Department Government of West Bengal Message from the Hon’ble Minister-in-Charge The Department of Backward Classes Welfare is dedicated to the welfare of Scheduled Castes; Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes with a view to integrate them ultimately with the mainstream of the society by effecting social, educational, economic and cultural uplift and thereby implement the provisions of the constitution of India concerning the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. 1. His Excellency the Hon’ble Governor of West Bengal in his address in the West Bengal Legislative Assembly has stressed that his Government will ensure speedy issue of Castes Certificates. With a backlog of pending 1,36,000 cases of Caste Certificates the department is now in a mode to issue all the pending cases immediately to honour the desire of His Excellency. 2. On review of the reports; it is evident that the reservation policy framed under the constitutional framework is not being followed by majority of the departments. 3 The various wings under this department like Pre-Examination Training Centers, Training cum Production Centers have been found to be literally non-functional. 4. Various educational institutions and programmes of department like Eklavya Schools, Ashram hostels, Central Hostels etc. needs a thorough Review. Such organizations being run with contractual staff and or on an ad hoc basis seem to have a dismally low efficiency level. 5. Cultural Research Institute (CRI)- the Research Wing of the department is found to be in a really sorry state and has literally stopped functioning with 55 posts lying vacant, a vehicle purchased for field research is not being used even for a single day and has been junked and even the signboard of the premier research institute lying on the ground shows the dismal state of affairs in an organization which could have been an example in the national scenario. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

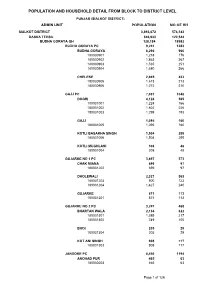

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI -

Family Size Ideals in Pakistan: Precarity and Uncertainty

Family Size Ideals in Pakistan: Precarity and Uncertainty Abstract Increasing contraceptive use and awareness of the benefits of a small family has been amongst the primary activities of the Pakistan’s family planning program. Despite their efforts, an ideal family size of four children has persisted in Pakistan for the last two decades. A significant body of literature has sought to disentangle and make sense of the dynamics informing these ideals in Pakistan. This work has highlighted financial insecurity, its effects on parents' aspirations for large families, and son preference. Missing, however, is an in-depth investigation of the social, economic, political, and cultural contexts in which family size ideals are embedded. We draw upon 13 months’ worth of ethnographic data from a village in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to situate family size ideals within their wider sociocultural, political, and economic context. Our findings demonstrate that respondents’ preference for larger families with several sons was an attempt to manage the precarity of daily life structured by regional conflict and violence, structural, intergenerational poverty, class-based exclusion from systems of power and patriarchy. These results allude to the importance of addressing the larger structural factors that contribute to large family size ideals. Introduction Established in 1965, Pakistan’s family planning program has sought to modify the fertility behaviour of Pakistani citizens by increasing their contraceptive use and awareness of the benefits of a small family (Robinson, Shah, and Shah 1981). Despite their efforts, an ideal family size of four children has persisted in the country since the 1990’s (Avan and Akhund 2006, National Institute of Population Studies 2013). -

Prayer-Guide-South-Asia.Pdf

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

The Influence of Arabic on Indian Language: Historically and Lingustically

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-2, Issue-11, Special Issue-1, Nov.-2016 THE INFLUENCE OF ARABIC ON INDIAN LANGUAGE: HISTORICALLY AND LINGUSTICALLY 1MUNA MOHAMMED ABBAS ALKHATEEB, 2HASANEIN HASAN 1,2College of Basic Education, Babylon University, IRAQ E-mail: ¹[email protected], ²[email protected] Abstract- Having talked with many people from India when we studied there from 2007 till 2014, we were often fascinated by words that sounded Arabic in origin. When asking about the meaning, they were indeed Arabic. And I could detect more words in the few Hindi Bollywood movies that I have seen as well. Historicallyspeaking , Arabic has been used in India almost exclusively by its Muslim population,and has been a key force in delineating and shaping Indian Muslim identity. This is not surprising, for it is generally acknowledged that the Arabic language has a predominantly sacred character outside the Arabic speaking Middle East. A thorough study of Indian history suggests that India's first substantial contact with the Arabic language came when the Arab Muslims settled in the western Indian province of Sind. Subsequently, the Arabic language continued to flourish further under the patronage of the Mughal rulers in India. In the Islamic epochs, the usage of Arabic was liturgical. But after the independence of India, non-sacred Arabic gained momentum. However, the functional manifestation of the language in the subcontinent has great historical significance and has not been systematically explored.To this end, this paper presents an attempt to analyze the processes and extent of development and uses of Arabic in India since its arrival in the eighth century through the twentieth indicating career prospects in the days to come, inasmuch as they bring into sharper focus the scriptural face of Indian Arabic. -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

Moreh-Namphalong Borders Trade

Moreh-Namphalong Borders Trade Marchang Reimeingam ISBN 978-81-7791-202-9 © 2015, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. MOREH-NAMPHALONG BORDER TRADE Marchang Reimeingam∗ Abstract Level of border trade (BT) taking place at Moreh-Namphalong markets along Indo-Myanmar border is low but significant. BT is immensely linked with the third economies like China which actually supply goods. Moreh BT accounts to two percent of the total India-Myanmar trade. It is affected by the bandh and strikes, insurgency, unstable currency exchange rate and smuggling that led to an economic lost for traders and economy at large. -

Sylhet, Bangladesh UPG 2018

Country State People Group Language Religion Bangladesh Sylhet Abdul Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Ansari Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Arleng Karbi Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, WesternOther / Small Bangladesh Sylhet Baiga Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bairagi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bania Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bauri Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Behara Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Beldar (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bhumij Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bihari (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Birjia Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bishnupriya Manipuri BishnupuriyaHinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bodo Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Gaur Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Joshi Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Kanaujia Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Radhi Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Sakaldwipi Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Saraswat Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin unspecified Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Utkal Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Vaidik Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Varendra Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Burmese Burmese Buddhism Bangladesh Sylhet Chamar (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Chero Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Chik Baraik Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Dai (Muslim traditions) Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Dalu Bengali Islam Bangladesh