Moreh-Namphalong Borders Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alasan Myanmar Menerima Diplomasi Indonesia Terkait Konflik Rohingya Periode 2015-2017

ALASAN MYANMAR MENERIMA DIPLOMASI INDONESIA TERKAIT KONFLIK ROHINGYA PERIODE 2015-2017 Skripsi Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Sosial (S.SOS) Oleh: Achmad Zulfani 11151130000048 PROGRAM STUDI HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 1441 H/2019 M I II ABSTRAK III Skripsi ini menganalisis alasan dari sikap terbuka Myanmar kepada Indonesia dalam bentuk penerimaan diplomasi Indonesia terkait konflik Rohingya periode 2015-2017. Terkait dengan konflik Rohingya yang mengalami eskalasi pada 2015 Myanmar bersikap cenderung tertutup kepada dunia dengan cara salah satunya menolak bantuan dari Perserikatan Bangsa-Bangsa (PBB). Hal tersebut didasari oleh respons dunia internasional seperti PBB dan Malaysia yang merespons dengan menggunakan megaphone diplomacy dan pandangan Myanmar bahwa konflik Rohingya merupakan konflik internal sehingga tidak ada negara yang berhak untuk mencampuri urusan internal Myanmar. Indonesia juga merespons konflik Rohingya dengan menggunakan diplomasi yang inklusif dan konstruktif, yaitu non-megaphone dan diplomasi publik yang intensif pada 2015-2017 dan menjadi negara yang diizinkan oleh Myanmar untuk ikut membantu konflik Rohingya. Skripsi ini menggunakan metode kualitatif dan deskriptif serta teknik pengumpulan data dilakukan melalui studi pustaka beserta wawancara dengan pihak- pihak terkait. Untuk menganalisis, skripsi ini menggunakan kerangka teoritis konstruktivisme dan konsep diplomasi publik, kedua hal tersebut -

Trade, Capital & Conflict

Logistical Spaces VIII Trade, Capital and Conflict: A Case Study of the Frontier Towns of Moreh-Tamu and Champhai Soma Ghosal & Snehashish Mitra 2017 Trade, Capital and Conflict: A Case Study of the Frontier Towns of Moreh-Tamu and Champhai ∗ Soma Ghosal and Snehashish Mitra The year 2017 is an eventful one in the development of Indo-Myanmar border trade. The Integrated Check Post (ICP), now under construction at Moreh gate No.1, will be operational within two months according to a statement by officials of the Land Port Authority of India under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and Mr. P.K Mishra, director (Projects) on their three days’ official visit to Moreh in the last week of August 2017. The ICP, observers believe, is a vital cog in India’s Look East, now Act East policy, aimed at integrating the economies of India and Southeast Asia through the northeast. In the year 2006 when the then Minister of State for Commerce, Mr. Jairam Ramesh, spoke of the Centre’s intention of investing Rs.70 crore for the project specifically as part of the Prime Minister’s Look East Policy, the only functional land customs station through which trade across the 1600 kms of Indo-Myanmar border took place was at Moreh. The ICP being built by RITES was then heralded by the Minister as a new concept aimed at managing both trade cargo and passenger movement across the border and providing modern infrastructure facilities and better connectivity. The ICP would greatly facilitate regional trade and would help the local community living in the border towns of Moreh and Tamu, he felt. -

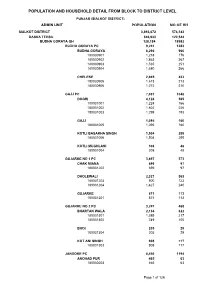

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI -

Statelessness in Myanmar

Statelessness in Myanmar Country Position Paper May 2019 Country Position Paper: Statelessness in Myanmar CONTENTS Summary of main issues ..................................................................................................................... 3 Relevant population data ................................................................................................................... 4 Rohingya population data .................................................................................................................. 4 Myanmar’s Citizenship law ................................................................................................................. 5 Racial Discrimination ............................................................................................................................... 6 Arbitrary deprivation of nationality ....................................................................................................... 7 The revocation of citizenship.................................................................................................................. 7 Failure to prevent childhood statelessness.......................................................................................... 7 Lack of naturalisation provisions ........................................................................................................... 8 Civil registration and documentation practices .............................................................................. 8 Lack of Access and Barriers -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

Download Full Text

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume:04, Issue:01 "January 2019" POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE BRITISH AND THE MANIPURI RESPONSES TO IT IN 1891 WAR Yumkhaibam Shyam Singh Associate Professor, Department of History Imphal College, Imphal, India ABSTRACT The kingdom of Manipur, now a state of India, neighbouring with Burma was occupied by the Burmese in 1819. The ruling family of Manipur, therefore, took shelter in the kingdom of Cachar (now in Assam) which shared border with British India. As the Burmese also occupied the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam and the Cachar Kingdom threatening the British India, the latter declared war against Burma in 1824. The Manipuris, under Gambhir Singh, agreed terms with the British and fought the war on the latter’s side. The British also established the Manipur Levy to wage the war and defend against the Burmese aggression thereafter. In the war (1824-1826), the Burmese were defeated and the kingdom of Manipur was re-established. But the British, conceptualizing political economy, ceded the Kabaw Valley of Manipur to Burma. This delicate issue, coupled with other haughty British acts towards Manipur, precipitated to the Anglo- Manipur War of 1891. In the beginning of the conflict when the British attacked the Manipuris on 24th March, 1891, the latter defeated them resulting in the killing of many British Officers. But on April 4, 1891, the Manipuris released 51 Hindustani/Gurkha sepoys of the British Army who were war prisoners then giving Rupees five each. Another important feature of the war was the involvement of almost all the major communities of Manipur showing their oneness against the colonial British Government. -

Internal Labour Migration in Myanmar: Building an Evidence-Base on Patterns in Migration, Human Trafficking

Internal Labour Migration in Myanmar Building an evidence-base on patterns in migration, human trafficking and forced labour International Labour Organization ILO Liaison Officer for Myanmar Report prepared by Kimberly Rogovin Myanmar translation by Daw Thet Hnin Aye Copyright © International Labour Organization 2015 First published 2015 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Internal labour migration in Myanmar: building an evidence-base on patterns in migration, human trafficking and forced labour; International Labour Organization, ILO Liaison Officer for Myanmar. - Yangon: ILO, 2015 x, 106 p. ISBN: 9789221303916; 9789221303923 (web pdf) International Labour Organization; ILO Liaison Officer for Myanmar labour migration / internal migration / trafficking in persons / forced labour / trend / methodology / Myanmar 14.09.1 Also available in Myanmar: ျမန္မာႏိုင္ငံအတြင္း ျပည္တြင္းေရႊ႕ေျပာင္းအလုပ္သမားမ်ား ျပည္တြင္းေရႊ႕ေျပာင္းအလုပ္ လုပ္ကုိင္ျခင္း၊ လူကုန္ကူးျခင္း၊ အဓမၼအလုပ္ခုိင္းေစမွႈဆုိင္ရာ ပုံစံမ်ားႏွင့္ ပတ္သက္ေသာ အေထာက္အထားအေျချပဳသက္ေသ တည္ေဆာက္ျခင္း (ISBN 9789228303919), Yangon, 2015. -

Conspiracy, God's Plan and National Emergency

CHAPTER EIGHT Conspiracy, God’s Plan and National Emergency Kachin Popular Analyses of the Ceasefire Era and its Resource Grabs Laur Kiik Introduction isiting Yangon in 2014, I noticed some well-meaning locals refer to the dragging Kachin military-political impasse by stat- ing: ‘The Kachins are being too stubborn, too emotional now’. OtherV observers find such talk belittling. They respond by emphasising how ‘The Kachins merely demand that Myanmar begin genuine political dialogue on federalism’ and ‘are thus correct in refusing simply to sign a new ceasefire’. This oscillation between explaining the Kachin impasse either through collective emotional trauma or through formal political discourse misses what Mandy Sadan identified in her monograph on Kachin histories as ‘social worlds beyond’.1 As this chapter tries to show, these are diverse, contradictory, and ambitious social worlds that people live within. They cannot be encapsulated by inaccurate and homogenis- ing expressions like ‘the Kachins’, ‘are emotional’, or ‘want federalism’. It is the argument of this chapter that the way people in these worlds understand their ceasefire experiences to express ethno-national emergency, divine predestination, and ethnocidal conspiracy influences directly their contemporary responses to ceasefire politics. 1. Mandy Sadan, Being and Becoming Kachin: Histories Beyond the State in the Border- worlds of Burma (Oxford: The British Academy and Oxford University Press, 2013), 455–60. 205 War and Peace in the Borderlands of Myanmar Figure 8.1: Many Kachin patriots are working for a future Kachin national modernity – a homeland yet-to-be (photo Hpauyam Awng Di). Many chapters in this volume refer to a hardening of Kachin na- tionalist rhetoric in recent years, in particular the chapters by Mahkaw Hkun Sa, Nhkum Bu Lu, Jenny Hedström, and Hkanhpa Tu Sadan. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

A Curriculum to Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2007 A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India Calvin N. Joshua Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Joshua, Calvin N., "A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India" (2007). Dissertation Projects DMin. 612. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/612 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA by Calvin N. Joshua Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA Name of researcher: Calvin N. Joshua Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce L. Bauer, DMiss. Date Completed: September 2007 Problem The dissertation project establishes the existence of nearly one hundred million tribal people who are forgotten but continue to live in human isolation from the main stream of Indian society. They have their own culture and history. How can the Adventist Church make a difference in reaching them? There is a need for trained pastors in tribal ministry who are culture sensitive and knowledgeable in missiological perspectives. Method Through historical, cultural, religious, and political analysis, tribal peoples and their challenges are identified. -

Directions for Tra Vellers on the Mystic Pa Th

DIRECTIONS FOR TRAVELLERS ON THE MYSTIC PA TH The publication ot this book was subsidized with a generous grant trom the Stichting Oosters Instituut in Leiden. VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 81 G. W. J. DREWES DIRECTIONS FOR TRAVELLERS ON THE MYSTIC PATH Zakariyyä' al-An~äri's Kitab FatJ;t al-RaJ;tman and its Indonesian Adaptations with an Appendix on Palembang manuscripts and authors THE HAGUE - MARTINUS NIJHOFF 1977 I.S.B.N. 90.247.2031.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Preface VII Introduction . Chapter I The author of the Risäla fi 'l-tawtzïd, Shaikh Wali Raslan of Damascus . 6 Chapter II The commentator, Zakariyya' al-An~äri, a "Pillar of Fiqh and T~awwur'. .... 26 Chapter III Kitäb Fattz al-Ratzmän, Zakariyyä' al-An~äri's com- mentary on Raslan's Risäla . 39 Chapter IV Kitab Patahulrahman, text and translation .. 52 Chapter V A Risalah by Shihabuddin of Palembang, text and English summary . 88 Chapter VI The so-called Kitab Mukhtasar by Kemas Fakh- ruddin of Palembang, text and translation 106 Notes and variae lectiones of cod.or. Leiden 7329 . 176 List of Arabic words and expressions . 191 Appendix Palembang manuscripts and authors Introduction 198 I. Manuscripts originating from Palembang . 199 II. Other manuscripts 214 lIl. Observations 217 IV. Palembang authors 219 V. Some observations on three works by unknown authors 229 VI. Hikayat Palembang . 234 Notes to Appendix . 238 List of manuscripts mentioned in the Appendix 242 Bibliography . 245 Index . • 252 PREFACE Many years ago in the Journalof the Batavia Society (T.B.G.), Vol. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South).