Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs on the History, Folk-Lore, and Distribution of The

' *. 'fftOPE!. , / . PEIHCETGIT \ rstC, juiv 1 THEOLOGICAL iilttTlKV'ki ' • ** ~V ' • Dive , I) S 4-30 Sect; £46 — .v-..2 SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/memoirsonhistory02elli ; MEMOIRS ON THE HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND DISTRIBUTION RACESOF THE OF THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES OF INDIA BEING AN AMPLIFIED EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS, BY THE J.ATE SIR HENRY M. ELLIOT, OF THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY’S BENGAL CIVIL SEBVICB. EDITED REVISED, AND RE-ARRANGED , BY JOHN BEAMES, M.R.A.S., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ; MEMBER OP THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OP PARIS AND BENGAL, AND OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIBTY OP LONDON. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., 8 and 60, PATERNOSTER ROWV MDCCCLXIX. [.All rights reserved STEPHEN AUSTIN, PRINTER, HERTFORD. ; *> »vv . SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. PART III. REVENUE AND OFFICIAL TERMS. [Under this head are included—1. All words in use in the revenue offices both of the past and present governments 2. Words descriptive of tenures, divisions of crops, fiscal accounts, like 3. and the ; Some articles relating to ancient territorial divisions, whether obsolete or still existing, with one or two geographical notices, which fall more appro- priately under this head than any other. —B.] Abkar, jlLT A distiller, a vendor of spirituous liquors. Abkari, or the tax on spirituous liquors, is noticed in the Glossary. With the initial a unaccented, Abkar means agriculture. Adabandi, The fixing a period for the performance of a contract or pay- ment of instalments. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Reconstructing the Population History of the Largest Tribe of India: the Dravidian Speaking Gond

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 493–498 & 2017 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 1018-4813/17 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Reconstructing the population history of the largest tribe of India: the Dravidian speaking Gond Gyaneshwer Chaubey*,1, Rakesh Tamang2,3, Erwan Pennarun1,PavanDubey4,NirajRai5, Rakesh Kumar Upadhyay6, Rajendra Prasad Meena7, Jayanti R Patel4,GeorgevanDriem8, Kumarasamy Thangaraj5, Mait Metspalu1 and Richard Villems1,9 The Gond comprise the largest tribal group of India with a population exceeding 12 million. Linguistically, the Gond belong to the Gondi–Manda subgroup of the South Central branch of the Dravidian language family. Ethnographers, anthropologists and linguists entertain mutually incompatible hypotheses on their origin. Genetic studies of these people have thus far suffered from the low resolution of the genetic data or the limited number of samples. Therefore, to gain a more comprehensive view on ancient ancestry and genetic affinities of the Gond with the neighbouring populations speaking Indo-European, Dravidian and Austroasiatic languages, we have studied four geographically distinct groups of Gond using high-resolution data. All the Gond groups share a common ancestry with a certain degree of isolation and differentiation. Our allele frequency and haplotype-based analyses reveal that the Gond share substantial genetic ancestry with the Indian Austroasiatic (ie, Munda) groups, rather than with the other Dravidian groups to whom they are most closely related linguistically. European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 493–498; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2016.198; published online 1 February 2017 INTRODUCTION material cultures, as preserved in the archaeological record, were The linguistic landscape of India is composed of four major language comparatively less developed.10–12 The combination of the more families and a number of language isolates and is largely associated rudimentary technological level of development of the resident with non-overlapping geographical divisions. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

Hanunó'o in Der Kongo, Republik Afghanen

Betet für die Unerreichten Betet für die Unerreichten Hanunó'o in der Kongo, Republik Afghanen, Tadschiken in Afghanistan Land: Republik Kongo Land: Afghanistan Volksgruppe: Hanunó'o Volksgruppe: Afghanen, Tadschiken Bevölkerung: 11.000 Bevölkerung: 10.585.000 Das Volk weltweit: 50.313.000 Das Volk weltweit: 10.986.000 Hauptsprache: Hausa Hauptsprache: Farsi, östlich (Dari) Hauptreligion: Islam Hauptreligion: Islam Status: Wenig erreicht Status: Wenig erreicht Gläubige: Zwischen 0 und 2% Gläubige: Zwischen 0 und 2% Bibel: Bibel Bibel: Bibel www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Alle Völker sind gerufen Gott anzubeten! Psalm 86:9 Alle Völker sind gerufen Gott anzubeten! Psalm 86:9 Betet für die Unerreichten Betet für die Unerreichten Afschar in Afghanistan Aimaken in Afghanistan Land: Afghanistan Land: Afghanistan Volksgruppe: Afschar Volksgruppe: Aimaken Bevölkerung: 15.000 Bevölkerung: 1.595.000 Das Volk weltweit: 393.000 Das Volk weltweit: 2.086.000 Hauptsprache: Aserbaidschanisch, südl Hauptsprache: Aimaq Hauptreligion: Islam Hauptreligion: Islam Status: Wenig erreicht Status: Wenig erreicht Gläubige: Zwischen 0 und 2% Gläubige: Zwischen 0 und 2% Bibel: Bibel Bibel: Übersetzung erforderlich www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Alle Völker sind gerufen Gott anzubeten! Psalm 86:9 Alle Völker sind gerufen Gott anzubeten! Psalm 86:9 Betet für die Unerreichten Betet für die Unerreichten Ansari in Afghanistan Araber, Tadschikische in Afghanistan Land: Afghanistan Land: Afghanistan Volksgruppe: Ansari Volksgruppe: Araber, Tadschikische -

Tribes in India

SIXTH SEMESTER (HONS) PAPER: DSE3T/ UNIT-I TRIBES IN INDIA Brief History: The tribal population is found in almost all parts of the world. India is one of the two largest concentrations of tribal population. The tribal community constitutes an important part of Indian social structure. Tribes are earliest communities as they are the first settlers. The tribal are said to be the original inhabitants of this land. These groups are still in primitive stage and often referred to as Primitive or Adavasis, Aborigines or Girijans and so on. The tribal population in India, according to 2011 census is 8.6%. At present India has the second largest population in the world next to Africa. Our most of the tribal population is concentrated in the eastern (West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Jharkhand) and central (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattishgarh, Andhra Pradesh) tribal belt. Among the major tribes, the population of Bhil is about six million followed by the Gond (about 5 million), the Santal (about 4 million), and the Oraon (about 2 million). Tribals are called variously in different countries. For instance, in the United States of America, they are known as ‘Red Indians’, in Australia as ‘Aborigines’, in the European countries as ‘Gypsys’ , in the African and Asian countries as ‘Tribals’. The term ‘tribes’ in the Indian context today are referred as ‘Scheduled Tribes’. These communities are regarded as the earliest among the present inhabitants of India. And it is considered that they have survived here with their unchanging ways of life for centuries. Many of the tribals are still in a primitive stage and far from the impact of modern civilization. -

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why It Is Needed Today?

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why it is needed today? By Premendra Priyadarshi1 Up to 1931, the Census of India included caste too. This practice was abandoned in 1941 because of protests by the nationalists, and also because it was considered worthless, misleading and a waste of time and energy. Column for religion was continued till 2001 census. Thereafter it was felt to be divisive and abandoned from 2011 census. Yet recently, there have been demands in political establishment for and against the caste census and the Union Government seems to be succumbing to pressures. It is desirable that we examine the perspectives of caste census. Why caste abandoned from census in 1941 The most important reason for abandonment of caste census was the ‗worthlessness‘ of the whole exercise because of inconsistency in caste names, which were not fixed and varied between districts, and with time, high incidence of unreliability of individuals‘ statement about caste etc. The Census Commissioner of India for 1931, J.H. Hutton noted, ―Sorting for caste is really worthless unless nomenclature is sufficiently fixed to render the resulting totals close and reliable approximations. Had caste terminology the stability of religious returns, caste sorting might be worthwhile. With the fluidity of current appellations it is certainly not… 227,000 Ambattans have become 10,000, Navithan, Nai, Nai Brahman, Navutiyan, Pariyari claim about 140,000—all terms unrecorded or untabulated in 1921.‖1 Only explanation for this could be that most of the Ambattans of 1921 changed into some other caste. Similarly, the number of Marathas in Central Provinces and Berar increased from 93,901 in 1911, to 206,144 in 1921.2 This more than 110% increase in number can be explained by the mass mobilization of Kunbis (Kurmi-s) to Marathas during the period. -

Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized

SFG2305 GPOBA for OBA Sanitation Microfinance Program in Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized Small Ethnic Communities and Vulnerable Peoples Development Framework (SECVPDF) May 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF) Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. Executive Summary 3 B. Introduction 5 1. Background and context 5 2. The GPOBA Sanitation Microfinance Programme 6 C. Social Impact Assessment 7 1. Ethnic Minorities/Indigenous Peoples in Bangladesh 7 2. Purpose of the Small Ethnic Communities and Vulnerable Peoples Development Framework (SECVPDF) 11 D. Information Disclosure, Consultation and Participation 11 E. Beneficial measures/unintended consequences 11 F. Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM) 12 G. Monitoring and reporting 12 H. Institutional arrangement 12 A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY With the Government of Bangladesh driving its National Sanitation Campaign from 2003-2012, Bangladesh has made significant progress in reducing open defecation, from 34 percent in 1990 to just once percent of the national population in 20151. Despite these achievements, much remains to be done if Bangladesh is to achieve universal improved2 sanitation coverage by 2030, in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Bangladesh’s current rate of improved sanitation is 61 percent, growing at only 1.1 percent annually. To achieve the SDGs, Bangladesh will need to provide almost 50 million rural people with access to improved sanitation, and ensure services are extended to Bangladesh’s rural poor. Many households in rural Bangladesh do not have sufficient cash on hand to upgrade sanitation systems, but can afford the cost if they are able to spread the cost over time. -

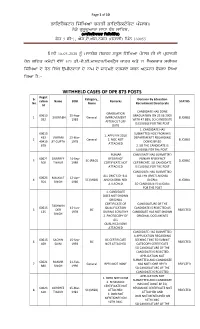

WITHHELD CASES of DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr

Page 1 of 10 fwierYktr is`iKAw BrqI fwierYktoryt pMjwb[ nyVy gurUduAwrw swcw DMn swihb, (mweIkrosw&t ibilifMg) Pyz 3 bI-1, AYs.ey.AYs.ngr (mohwlI) ipMn 160055 imqI 16.03.2020 nUM mwnXog s`kqr skUl is`iKAw pMjwb jI dI pRDwngI hyT giTq kmytI v`loN 873 fI.pI.eI.mwstr/imstRYs kwfr Aqy 74 lYkcrwr srIrk is`iKAw dy hyT ilKy aumIdvwrW dy nwm dy swhmxy drswey kQn Anuswr PYslw ilAw igAw hY:- WITHHELD CASES OF DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr. Category_ Decision By Education ration Name DOB Remarks STATUS No. Name Recruitment Directorate Id CANDIDATE HAS DONE GRADUATION 60610 25-Aug- GRADUATION ON 25.06.2005 1 SAURABH General IMPROVEMENT ELIGIBLE 352 1983 WITH 47.88%, SO CANDIDATE AFTER CUT OFF IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST DATE 1. CANDIDATE HAS 60613 SUBMITTED NOC FROM HIS 1. APPLY IN 2016 433 VIKRAM 23-Mar- DEPARTMENTT REGARDING 2 General 2. NOC NOT ELIGIBLE 40410 JIT GUPTA 1978 DOING BP.ED ATTACHED 679 2. SO THE CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST. PUNJAB CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED 60621 GURPREE 14-Sep- RESIDENCE PUNJAB RESIDENCE 3 SC (R&O) ELIGIBLE 500 T KAUR 1989 CERTIFICATE NOT CERTIFICATE SO CANDIDATE ATTACHED IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED ALL DMC'S OF B.A. ALL THE DMC'S AND BA 60625 MALKEET 12-Apr- 4 SC (M&B) AND DEGREE NOT DEGREE ELIGIBLE 504 SINGH 1986 ATTACHED SO CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST 1. CANDIDATE DOES NOT SHOWN ORIGINAL CERTIFICATE OF CANDIDATURE OF THE TASHWIN 60615 15-Jun- QUALIFICATION CANDIDATE IS REJECTED AS 5 DER BC REJECTED 125 1978 DURING SCRUTINY CANDIDATE HAS NOT SHOWN SINGH 2. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known.