Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs on the History, Folk-Lore, and Distribution of The

' *. 'fftOPE!. , / . PEIHCETGIT \ rstC, juiv 1 THEOLOGICAL iilttTlKV'ki ' • ** ~V ' • Dive , I) S 4-30 Sect; £46 — .v-..2 SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/memoirsonhistory02elli ; MEMOIRS ON THE HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND DISTRIBUTION RACESOF THE OF THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES OF INDIA BEING AN AMPLIFIED EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS, BY THE J.ATE SIR HENRY M. ELLIOT, OF THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY’S BENGAL CIVIL SEBVICB. EDITED REVISED, AND RE-ARRANGED , BY JOHN BEAMES, M.R.A.S., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ; MEMBER OP THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OP PARIS AND BENGAL, AND OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIBTY OP LONDON. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., 8 and 60, PATERNOSTER ROWV MDCCCLXIX. [.All rights reserved STEPHEN AUSTIN, PRINTER, HERTFORD. ; *> »vv . SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. PART III. REVENUE AND OFFICIAL TERMS. [Under this head are included—1. All words in use in the revenue offices both of the past and present governments 2. Words descriptive of tenures, divisions of crops, fiscal accounts, like 3. and the ; Some articles relating to ancient territorial divisions, whether obsolete or still existing, with one or two geographical notices, which fall more appro- priately under this head than any other. —B.] Abkar, jlLT A distiller, a vendor of spirituous liquors. Abkari, or the tax on spirituous liquors, is noticed in the Glossary. With the initial a unaccented, Abkar means agriculture. Adabandi, The fixing a period for the performance of a contract or pay- ment of instalments. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

District Population Statistics, 45-Kheri, Uttar Pradesh

Census' of India, 1951 ·DISTRICT POPULATION STATISTICS UTTAR PRADESH 45-KHERI DISTRlCT· • 1 I 315.42 1111 KHEDPS . OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR . GENERAL, INDIA, NEW DELHI . 82011 ( LIBRARY) Class No._ 315.42 Book No._ 1951 KHE DPS 21246 Accession 1\10. ________ >ULED CASTES IN UTTAR PRADESH _h.e Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950] ~~~~-------------------------------- (1) Throughout the State- <H Agariya (22) Bhuyi6l' (43) Kanjar (2) Badi . (23) Boria . (44) Kap6l'iya (3) Badhik (24) Chamar (45) Karwal (4) Baheliya (25) Chero (46) Khaira.hA (5) B&iaa (26) Dabgar t47) Kharot. (b) Baisw6l' (27) Dhangar (48) KJia.rw6l' (excluding Benbl\llSj) (7) Bajaniya (28) Dhanuk (49) Kol (8) Bajgi (29) Dbarkar (50) Korwa (9) Balahar (30) DhQbi (51) Lalbegi /(I0) Ba,lmiki (31) Dhusia OJ' Jhusia _ (52) Majhw6l' (II) Bangali (32) Dom j53) Nat ~ (12) Banmanus (33) DOmar (54) Panltha (13) Bansphor (34) Dusadh ;I (55) Par~ya (l~) Barwar (3"5). GhMami (56) P~i . (15) Basor (36) Ghasiya (57) Patari (16) Bawariya (37) Gual (58) Rawat (17) Beldar (38) Habura. (59) Saharya (lS) Seriya. (39) Hilori (60, Salia.urhiyllo (19) Bha.n.tu (40}'He~ (61) StmBiya . (20) Bhoksa (41) .Jatava (621 Shilpkar (21) Bhuiya (42) Kalaha7l (63) Turaiha (2) In B'Undelkhand Division and the portion 0/ Mi~,ap'U;',District,'~(Juth of Kaimu,. > Rang.e- . -, .'- Gond FOREWORD THE Uttar Pradesh Government asked me in March, 1952, to supply them for the purposes of elections to local bodies population statistics with separation for scheduled castes (i) mohallaJward-wise for urban areas, and (ii) village-wise for rural areas. -

A Historical Transition of Banjara Community in India with Special Reference to South India Nagaveni T

Research Journal of Recent Sciences _________________________________________________ ISSN 2277-2502 Vol. 4(ISC-2014), 11-15 (2015) Res. J. Recent. Sci. A Historical Transition of Banjara Community in India with Special Reference to South India Nagaveni T. Department of History, Government First Grade College, Kuvempunagar, Mysore-570 023, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 13 rd November 2014, revised 9th March 2015, accepted 25 th March 2015 Abstract An incisive insight into the literature on Banjara Community clearly indicates that ample literature has been produced by the Western and Indian scholars. Yet the treatment of the problem is exponential. Deep delve into the process of historical transition of the Banjara Community enables us to focus on various controversial issues and complexities of historical significance. Issues like Semantics, Historicity, Location, Ethnicity, Categorization, Caste-clan, Dichotomy and the community’s identity continued to gravitate the attention of the scholars and researchers alike. Lack of unanimity among the scholars and policy makers on these contentious issues has added perplexity to the puzzle. Ambiguous explanations given by the community historians have further complicated the clear-cut understanding of the process of historical transition. The antiquity of this Banjara Community is traceable to Harappa and Mohenjodaro. Its influence continued to spread and retain its relevance down the centuries to shape and reshape the course of history. There is a speculation about the group of Banjaras who mere concentrated outside India and called as Roma Gypsy, where their social history is not yet clear but proved to be of Indian Origin. This paper however strives to focus on historical transition within the context of India from 13 th Century A.D. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

Tribes in India 208 Reading

Department of Social Work Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Regional Campus Manipur Name of The Paper: Tribal Development (218) Semester: IV Course Faculty: Ajeet Kumar Pankaj Disclaimer There is no claim of the originality of the material and it given only for students to study. This is mare compilation from various books, articles, and magazine for the students. A Substantial portion of reading is from compiled reading of Algappa University and IGNOU. UNIT I Tribes: Definition Concept of Tribes Tribes of India: Definition Characteristics of the tribal community Historical Background of Tribes- Socio- economic Condition of Tribes in Pre and Post Colonial Period Culture and Language of Major Tribes PVTGs Geographical Distribution of Tribes MoTA Constitutional Safeguards UNIT II Understanding Tribal Culture in India-Melas, Festivals, and Yatras Ghotul Samakka Sarakka Festival North East Tribal Festival Food habits, Religion, and Lifestyle Tribal Culture and Economy UNIT III Contemporary Issues of Tribes-Health, Education, Livelihood, Migration, Displacement, Divorce, Domestic Violence and Dowry UNIT IV Tribal Movement and Tribal Leaders, Land Reform Movement, The Santhal Insurrection, The Munda Rebellion, The Bodo Movement, Jharkhand Movement, Introduction and Origine of other Major Tribal Movement of India and its Impact, Tribal Human Rights UNIT V Policies and Programmes: Government Interventions for Tribal Development Role of Tribes in Economic Growth Importance of Education Role of Social Work Definition Of Tribe A series of definition have been offered by the earlier Anthropologists like Morgan, Tylor, Perry, Rivers, and Lowie to cover a social group known as tribe. These definitions are, by no means complete and these professional Anthropologists have not been able to develop a set of precise indices to classify groups as ―tribalǁ or ―non tribalǁ. -

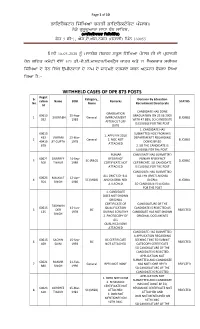

WITHHELD CASES of DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr

Page 1 of 10 fwierYktr is`iKAw BrqI fwierYktoryt pMjwb[ nyVy gurUduAwrw swcw DMn swihb, (mweIkrosw&t ibilifMg) Pyz 3 bI-1, AYs.ey.AYs.ngr (mohwlI) ipMn 160055 imqI 16.03.2020 nUM mwnXog s`kqr skUl is`iKAw pMjwb jI dI pRDwngI hyT giTq kmytI v`loN 873 fI.pI.eI.mwstr/imstRYs kwfr Aqy 74 lYkcrwr srIrk is`iKAw dy hyT ilKy aumIdvwrW dy nwm dy swhmxy drswey kQn Anuswr PYslw ilAw igAw hY:- WITHHELD CASES OF DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr. Category_ Decision By Education ration Name DOB Remarks STATUS No. Name Recruitment Directorate Id CANDIDATE HAS DONE GRADUATION 60610 25-Aug- GRADUATION ON 25.06.2005 1 SAURABH General IMPROVEMENT ELIGIBLE 352 1983 WITH 47.88%, SO CANDIDATE AFTER CUT OFF IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST DATE 1. CANDIDATE HAS 60613 SUBMITTED NOC FROM HIS 1. APPLY IN 2016 433 VIKRAM 23-Mar- DEPARTMENTT REGARDING 2 General 2. NOC NOT ELIGIBLE 40410 JIT GUPTA 1978 DOING BP.ED ATTACHED 679 2. SO THE CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST. PUNJAB CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED 60621 GURPREE 14-Sep- RESIDENCE PUNJAB RESIDENCE 3 SC (R&O) ELIGIBLE 500 T KAUR 1989 CERTIFICATE NOT CERTIFICATE SO CANDIDATE ATTACHED IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED ALL DMC'S OF B.A. ALL THE DMC'S AND BA 60625 MALKEET 12-Apr- 4 SC (M&B) AND DEGREE NOT DEGREE ELIGIBLE 504 SINGH 1986 ATTACHED SO CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST 1. CANDIDATE DOES NOT SHOWN ORIGINAL CERTIFICATE OF CANDIDATURE OF THE TASHWIN 60615 15-Jun- QUALIFICATION CANDIDATE IS REJECTED AS 5 DER BC REJECTED 125 1978 DURING SCRUTINY CANDIDATE HAS NOT SHOWN SINGH 2. -

JMC FINAL REPORT 2015-16 FINAL NEW 1254.Xlsx

-! JALGAOI{ MUNICIPAL CORPORATION DIST: . JALGAON FINANCIAL STATE,MENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 04l-4t201s To 31103t2016 PREPARED BY :- e - S. S. LODHA & ASSOCIATES - CHARTERED ACCOUNTAI{TS 16117, FIRST FLOOR, OLD B.J. MARKET, JALGAON- 425OOI. - : f, s I ^ru{ts-- 'L\)y\l\t I -- : t 1' JALGAON CITY MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, JALGAON Balance Sheet As on 3110312016 lt Accou nl Schedule 2015-2016 2014-2015 1- Liabilities t_ Code No Amount ( Rs ) Amount ( Rs ) I I 3100 Municipal Fund & Reserryes B-1 803811883.58 529884448.18 : 3200 Grants Contribution for Speci{ic Purpose B.-2 738174958.60 49364s47s.60 t Loans B-3 1792639899.00 1861948199.00 t 3300 Secured & Unsecured I Current Liabilities & Provisions 3400 Interest on Loan B-4 t994025627.00 2t921 10842.00 I 3500 Employers Liability B-5 287709817.78 305720483.45 3600 Suppliers, Contractors & Other Liabilities B-6 342t87646.53 362656242.03 i 3700 Liability to citizens B-7 17s000.00 512543.00 - 3800 Amount Payable to Government B-8 9067420.50 13501271.00 3900 Others liabilites B-9 62456298.00 40257678.00 Total Current Liabilities & Provisions 2695621809.81 29147s9059.48 -\< Grand Total of Liabilities 6030248550.99 5800237182.26 -Li{ Account Schedule f- Assets Code No t -t! Fixed Assets : - 4100 Fixed & Movable Assets B-10 s949806750.80 5935506878.80 t 4200 Less :- Accumulated Depreciation B-11 (1880197740.16) (18791s8193.i6) 4300 Capital Work in Progress 0.00 0.00 L.-I Total F'ixed Assets 4069609010.64 4056348685.64 l' b--I 4400 Investments B-12 245133855.73 219815705.73 i \ Current Assets : - 4500 -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Scheduled Tribes

Annual Report 2008-09 Ministry of Tribal Affairs Photographs Courtesy: Front Cover - Old Bonda by Shri Guntaka Gopala Reddy Back Cover - Dha Tribal in Wheat Land by Shri Vanam Paparao CONTENTS Chapters 1 Highlights of 2008-09 1-4 2 Activities of Ministry of Tribal Affairs- An Overview 5-7 3 The Ministry: An Introduction 8-16 4 National Commission for Scheduled Tribes 17-19 5 Tribal Development Strategy and Programmes 20-23 6 The Scheduled Tribes and the Scheduled Area 24-86 7 Programmes under Special Central Assistance to Tribal Sub-Plan 87-98 (SCA to TSP) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution 8 Programmes for Promotion of Education 99-114 9 Programmes for Support to Tribal Cooperative Marketing 115-124 Development Federation of India Ltd. and State level Corporations 10 Programmes for Promotion of Voluntary Action 125-164 11 Programmes for Development of Particularly Vulnerable 165-175 Tribal Groups (PTGs) 12 Research, Information and Mass Media 176-187 13 Focus on the North Eastern States 188-191 14 Right to Information Act, 2005 192-195 15 Draft National Tribal Policy 196-197 16 Displacement, Resettlement and Rehabilitation of Scheduled Tribes 198 17 Gender Issues 199-205 Annexures 3-A Organisation Chart - Ministry of Tribal Affairs 13 3-B Statement showing details of BE, RE & Expenditure 14-16 (Plan) for the years 2006-07, 2007-08 & 2008-09 5-A State-wise / UT- wise details of Annual Plan (AP) outlays for 2008-09 23 & status of the TSP formulated by States for Annual Plan (AP) 2008-09. 6-A Demographic Statistics : 2001 Census 38-39 -

ORDER Since a Corona Positive Case Has Been Reported from VRDL

ORDER Since a Corona positive case has been reported from VRDL, Department of Microbiology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Science, Rohtak in Bazigar Mohalla Tohana, Tehsil Tohana District Fatehabad, therefore, the geographical area falling under Bazigar Mohalla from the house of Sh. Baba Ram S/o Sh. Jamal Ram near Jaimal Dairy Bazigar Mohalla to Sh. Vijay S/o Sh. Ramparsad Killa Mohalla Tohana and Bazigar Mohalla from H/o Darbara Saini Halwai and Sultan Bazigar Sant Baba Jandapuri Mandir to H/o Sh. Mahender Singh S/o Sh. Gurmel Singh and H/o Sh. Prithvi S/o Sh. Narata Killa Mohalla Tohana of Tehsil Tohana District Fateahbad is declared as Containment Zone and rest of the area of Bazigar Mohalla, Balmiki Mohalla, Killa Mohalla, Harpal Chowk and Naya Bazar are delclared as Buffer Zone for all the purposes and objective as prescribed in the protocol of nCOVID-19 District Containment Plan (Health Department) to prevent its spread in the adjoining areas. For combating the situation at hand, the following action plan is prescribed to carry out screening of the suspects, testing of all suspected cases, quarantine, isolation, social distancing and other public health measures in the Containment Zone as well as Buffer Zone effectively: 1. 10 Teams comprising of Anganwadi Workers, Asha Workers, MPHW (Male) and ANMs for conducting door to door screening/thermal scanning of each and every person of the entire households falling in the Containment Zone shall be deployed by the Civil Surgeon, Fatehabad and each team would be allocated 25 households. Two Anganwari Supervisors and one WCDPO would be deployed to supervise the work to be carried out by the Asha Workers, Anganwadi workers, MPHW (Male) and ANMs. -

Literature Review in India: - a Case Study of Gujjar and Bakerwals

Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 Literature Review in India: - A Case Study of Gujjar and Bakerwals Dr. Raja Shahid Mughal Abstract Gujjars and Bakerwals are two names of one tribe popularly known as Gujjars in Indian sub- continent. Gujjars form an important ethnic and linguistic group. A country like India is a place to a variety of population with their separate culture, traditions and living styles. India is a home to almost more than half of the world’s tribal population. Gujrat, the state of India, was once called as Gujjar- Rashtra, which indicate the meaning Kingdom of Gujjar’s. From this area Gujjar’s established their kingdom and spread over other parts of the country.In this paper I describe the almost whole review about the literature of Gujjar and Bakerwals . Keyword:- Culture, Nomadic Life, Tribals, Gujari (Gojri), Gujjar Bakarwal tribals. Introduction Various studies have been conducted to discuss and analyze the different dimensions of the tribal life in India. Therefore, available relevant studies have been critically reviewed. Hudson (1922) in his book entitled “The Primitive Culture of India” traced the complex historical evaluation of various tribes of India and Hulton (1941) examined their socio- cultural condition. Ghurye (1943) argued that the tribals were backward caste Hindus. He at that time also held that they should be given equal status like the other Hindus. Majumdar (1944) following Ghurye‟s argument suggested that the cultural identity of tribals should be secured for which he stressed that there should be 'selected integration' of the tribals. Explaining it in detail he further held that only those people should be permitted to enter in this community who have relevance with tribal life.