Tribes in India 208 Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2012-13.Pdf

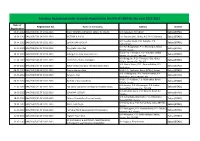

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2012-2013 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 09-04-2012 BAK/260/E/01 OF 2012-2013 JEUTY GRAMYA UNNAYAN SAMITTEE (JGUS) Vill. Batiamari, PO Kalbari Baksa (BTAD) 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/02 OF 2012-2013 VICTORY-X N.G.O. H.O. Barama (Niz-Juluki), P.O. & P.S. Barama Baksa (BTAD) Vill. Katajhar Gaon, P.O. Katajhar, P.S. 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/03 OF 2012-2013 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Baksa (BTAD) Gobardhana Vill.-Pub Bangnabari, P.O.-Mushalpur, Baksa 11-04-2012 BAK/260/E/04 OF 2012-2013 Daugaphu Aiju Afad Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. Vill. & P.O.-Tamulpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Baksa 24-04-2012 BAK/260/E/05 OF 2012-2013 Udangshree Jana Sewa Samittee Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367 Vill.-Baregaon, P.O.- Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 27-04-2012 BAK/260/E/06 OF 2012-2013 RamDhenu N.g.o., Baregaon Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Natun Sripur, P.O.- Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/07 OF 2012-2013 Natun Sripur (Sonapur /Khristan Basti) Baro Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/08 OF 2012-2013 Dodere Harimu Afat Vill.& P.O.-Laukhata, Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa (BTAD) Vill.-Goldingpara, P.O.-Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/09 OF 2012-2013 Jwngma Afat Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, Baksa (BTAD), Ass. Vill.& P.O.-Adalbari, P.S.-Mushalpur, Baksa 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/10 OF 2012-2013 Barhukha Sport Academy Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

View Entire Book

Orissa Review * April-May - 2009 Integration of Princely States Under Dr. Harekrushna Mahtab Balabhadra Ghadai The Constitution of Orissa Order-1936 got the different parts of the Princely States in Orissa. In approval of the British king on 3rd March, 1936. 1938 Praja Mandals (People's Association) were It was announced that the new province would formed and under their banner, struggle began come into being on 1st April, 1936 with Sir John for securing democratic rights. In the Princely State Austin Hubback, I.C.S. as the Governor. On the of Talcher a movement against feudal exploitation appointed day in a solemn ceremony held at the made significant advance. There was unrest at Ravenshaw College Hall, Cuttack, Sir John Austin Dhenkanal also where the Ruler tried his best to Hubback was administered the oath of office by suppress it. In October 1938, six persons including Sir Courtney Terrel, the Chief Justice of Bihar a 12 year old boy named Baji Rout died as a and Orissa High Court. The Governor read out result of firing. In Ranpur there was an out-break the message of goodwill received from the king- of lawlessness and the situation became serious emperor George VI and the Viceroy of India in January 1939 when the Political Agent Major Lord Linlithgow, for the people of Orissa. Thus, R.L. Bazelgatte was messacred by the mob on 5 the long cherished dream of the Oriya speaking January, 1939 at Ranpur. The troops were sent people of years at last became a reality. to crush the people's movement. -

Ethnolinguistic Survey of Westernmost Arunachal Pradesh: a Fieldworker’S Impressions1

This is the version of the article/chapter accepted for publication in Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 37 (2). pp. 198-239 published by John Benjamins : https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.37.2.03bod This material is under copyright and that the publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34638 ETHNOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF WESTERNMOST ARUNACHAL PRADESH: A FIELDWORKER’S IMPRESSIONS1 Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Timotheus Adrianus Bodt Volume xx.x - University of Bern, Switzerland/Tezpur University, India The area between Bhutan in the west, Tibet in the north, the Kameng river in the east and Assam in the south is home to at least six distinct phyla of the Trans-Himalayan (Tibeto-Burman, Sino- Tibetan) language family. These phyla encompass a minimum of 11, but probably 15 or even more mutually unintelligible languages, all showing considerable internal dialect variation. Previous literature provided largely incomplete or incorrect accounts of these phyla. Based on recent field research, this article discusses in detail the several languages of four phyla whose speakers are included in the Monpa Scheduled Tribe, providing the most accurate speaker data, geographical distribution, internal variation and degree of endangerment. The article also provides some insights into the historical background of the area and the impact this has had on the distribution of the ethnolinguistic groups. Keywords: Arunachal Pradesh, Tibeto-Burman, Trans-Himalayan, Monpa 1. INTRODUCTION Arunachal Pradesh is ethnically and linguistically the most diverse state of India. -

Tribes in India

SIXTH SEMESTER (HONS) PAPER: DSE3T/ UNIT-I TRIBES IN INDIA Brief History: The tribal population is found in almost all parts of the world. India is one of the two largest concentrations of tribal population. The tribal community constitutes an important part of Indian social structure. Tribes are earliest communities as they are the first settlers. The tribal are said to be the original inhabitants of this land. These groups are still in primitive stage and often referred to as Primitive or Adavasis, Aborigines or Girijans and so on. The tribal population in India, according to 2011 census is 8.6%. At present India has the second largest population in the world next to Africa. Our most of the tribal population is concentrated in the eastern (West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Jharkhand) and central (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattishgarh, Andhra Pradesh) tribal belt. Among the major tribes, the population of Bhil is about six million followed by the Gond (about 5 million), the Santal (about 4 million), and the Oraon (about 2 million). Tribals are called variously in different countries. For instance, in the United States of America, they are known as ‘Red Indians’, in Australia as ‘Aborigines’, in the European countries as ‘Gypsys’ , in the African and Asian countries as ‘Tribals’. The term ‘tribes’ in the Indian context today are referred as ‘Scheduled Tribes’. These communities are regarded as the earliest among the present inhabitants of India. And it is considered that they have survived here with their unchanging ways of life for centuries. Many of the tribals are still in a primitive stage and far from the impact of modern civilization. -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

Unit-26 History and Geographical Spread

UNIT-26 HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD . Structure 26.0 Objectives 26.1 Introduction 26.2 Cultural Pattern . 26.3 Geographical Spread:Tribal Zones 263.1, Northern and North-Eastern 2633' Central _ 2633 . South-Western 263.4 . Scattered 26.4 History, Language and Ethnicity 26.4.1 Northern and North-eakern Tribes 26.42 Central Indian Tribes 26.43 South-Western Tribes 26.4.4 Scattered Tribes 265 Let Us Sum Up 26.6 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A DaMa Tribal Girl, Gqjarat. Appendix ( 26.0 OBJECTIVES ; i, This Unit attempts to analyse history and geographical spread of tribes. After reading this unit you uould know about : / cultural spread of tribes, and , the tribal culture with respect to its history and geographical spread in the Northern, NorthiEastem, Central, South-Westem, and scattered zones, and 1 languhges and ethnicity of a few tribes. { 26.1 INTRODUCTION -+ The tribal groups are presumed to form the oldest ethnological sector of the national population. Tribal population of India is spread all over the country. However, in Haryana, Punjab,Chandigarh, DeUli,Goa and Pondicherry there exist very little tribal population.The rest of the states and union territories possess fairly good number of tribal population. You wiU find that forest and hilly areas possess greater concentration of tribal population; while in the plains their number isquite less. Madhya Pradesh registers the largest number oftribes (73) followed by Anrnachal Pradesh (62), Orissa (56), Maharashtra (52), Andhra Pradesh (43), etc. The vast variety and numbers of Indian tribes and tribal groups have\always been a matter of great social and literary discourse for the past several decades. -

Scheduled Tribes

Annual Report 2008-09 Ministry of Tribal Affairs Photographs Courtesy: Front Cover - Old Bonda by Shri Guntaka Gopala Reddy Back Cover - Dha Tribal in Wheat Land by Shri Vanam Paparao CONTENTS Chapters 1 Highlights of 2008-09 1-4 2 Activities of Ministry of Tribal Affairs- An Overview 5-7 3 The Ministry: An Introduction 8-16 4 National Commission for Scheduled Tribes 17-19 5 Tribal Development Strategy and Programmes 20-23 6 The Scheduled Tribes and the Scheduled Area 24-86 7 Programmes under Special Central Assistance to Tribal Sub-Plan 87-98 (SCA to TSP) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution 8 Programmes for Promotion of Education 99-114 9 Programmes for Support to Tribal Cooperative Marketing 115-124 Development Federation of India Ltd. and State level Corporations 10 Programmes for Promotion of Voluntary Action 125-164 11 Programmes for Development of Particularly Vulnerable 165-175 Tribal Groups (PTGs) 12 Research, Information and Mass Media 176-187 13 Focus on the North Eastern States 188-191 14 Right to Information Act, 2005 192-195 15 Draft National Tribal Policy 196-197 16 Displacement, Resettlement and Rehabilitation of Scheduled Tribes 198 17 Gender Issues 199-205 Annexures 3-A Organisation Chart - Ministry of Tribal Affairs 13 3-B Statement showing details of BE, RE & Expenditure 14-16 (Plan) for the years 2006-07, 2007-08 & 2008-09 5-A State-wise / UT- wise details of Annual Plan (AP) outlays for 2008-09 23 & status of the TSP formulated by States for Annual Plan (AP) 2008-09. 6-A Demographic Statistics : 2001 Census 38-39 -

Glossary on Scheduled Tribes Of

CENSUS OF INDIA~ 1961 MADHYA PRADESH GLOSSARY ON SCHEDULED TRIBES OF MADHYA PRADESH Hy K. C. DUBEY, Deputy Superintendent, Census Operations, Madhya Pradesh. 1969 In ,the '1961 Census it was origina11y proposed to prepare ethnographic notes on all the principal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes of Madhya Pradesh. Some work had been done in this direction and notes on some tribes were also prepared. However, for various reasons the project on ethnographic notes could not be completed. We in the State Census Office thought that whether or not the ethnographic notes are prepared, compilation of a glossary on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes would be" very useful to all concerned. It 'will' show the population for all Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and synonymous groups li'sted in the Sche.duled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Li.sts (Modification) Order, 1956 which information is not available in the Census publications and it will help to briefly introduce all such Scheduled Caste s, Scpeduled Tribe s and synonymous groups. 'l'he glossary, it was thought, would be more welcome to general administration thrul the detailed ethnographic note s. Thus, the preparation of glossary on Scheduled Tribes was taken in hand in 1963 ~~d it was eompleted in 1964. Because of various other·pre-occupations a similar glossary on Scheduled Castes could not be prepared. 'The g1.ossar~' prepared at the State Census Office was submitted to the Social Studies Section of the ~1Jin- cl . Registrar General. It was scrutinised there and the suggestions received from the Registrar General were incorporated in the glossary. -

Rengma Nagas Demand Autonomous Council

Rengma Nagas demand autonomous council They write to Union Home Minister and Assam Chief Minister, asking for their voices to be heard Vijaita Singh have no history in the Reng- the Rengma Nagas, whose New Delhi ma Hills. People who are population is around The Rengma Nagas in Assam presently living in Rengma 22,000. We are also de- have written to Union Home Hills are from Assam, Aruna- manding a separate legisla- Minister Amit Shah demand- chal Pradesh and Meghalaya. tive seat for Rengmas,” he ing an autonomous district They speak different dialects said. council amid a decision by and do not know Karbi lan- The National Socialist the Central and the State go- guage of Karbi Anglong,” the Council of Nagaland or NSCN vernments to upgrade the memorandum said. (Isak-Muivah), which is in Karbi Anglong Autonomous RNPC president K. Solo- talks with the Centre for a Council (KAAC) into a terri- mon Rengma told The Hindu peace deal, said in a state- torial council. that the government was on ment on Monday that the The Rengma Naga Peo- the verge of taking a decision Rengma issue was one of the ples’ Council (RNPC), a regis- Long fight:The Rengma Naga community has been seeking without taking them on important agendas of the tered body, said in the mem- board and thus they had “Indo-Naga political talks” an automous council for many years now. * FILE PHOTO orandum that the Rengmas written to Mr. Shah and and no authority should go were the first tribal people in Narrating its history, the sam and Nagaland at the Chief Minister Himanta Bis- far enough to override their Assam to have encountered council said that during the time of creation of Nagaland wa Sarma. -

Constituent Assembly Debates Official Report

Volume VII 4-11-1948 to 8-1-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed by JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President : THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD Vice-President : DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE Constitutional Adviser : SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary : SHRI H.V. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary : SHRI S.N. MUKERJEE Deputy Secretary : SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA Under Secretary : SHRI K.V. PADMANABHAN Marshal : SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS RAI JAIDKA CONTENTS ————— Volume VII—4th November 1948 to 8th January 1949 Pages Pages Thursday, 4th November 1948 Thursday, 18th November, 1948— Presentation of Credentials and Taking the Pledge and Signing signing the Register .................. 1 the Register ............................... 453 Taking of the Pledge ...................... 1 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 453—472 Homage to the Father of the Nation ........................................ 1 [Articles 3 and 4 considered] Condolence on the deaths of Friday, 19th November 1948— Quaid-E-Azam Mohammad Ali Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 473—500 Jinnah, Shri D.P. Khaitan and [Articles 28 to 30-A considered] Shri D.S. Gurung ...................... 1 Amendments to Constituent Monday, 22nd November 1948— Assembly Rules 5-A and 5-B .. 2—12 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 501—527 Amendment to the Annexure to the [Articles 30-A, 31 and 31-A Schedule .................................... 12—15 considered] Addition of New Rule 38V ........... 15—17 Tuesday, 23rd November 1948— Programme of Business .................. 17—31 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 529—554 Motion re Draft Constitution ......... 31—47 Appendices— [Articles 32, 33, 34, 34-A, 35, 36, 37 Appendix “A” ............................. -

Madhya Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2000 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Part I Preliminary Sections 1

THE MADHYA PRADESH REORGANISATION ACT, 2000 _____________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS _____________ PART I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II REORGANISATION OF THE STATE OF MADHYA PRADESH 3. Formation of Chhattisgarh State. 4. State of Madhya Pradesh and territorial divisions thereof. 5. Amendment of the First Schedule to the Constitution. 6. Saving powers of the State Government. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES The Council of States 7. Amendment of the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 8. Allocation of sitting members. The House of the People 9. Representation in the House of the People. 10. Delimitation of Parliamentary and Assembly constituencies. 11. Provision as to sitting members. The Legislative Assembly 12. Provisions as to Legislative Assemblies. 13. Allocation of sitting members. 14. Duration of Legislative Assemblies. 15. Speakers and Deputy Speakers. 16. Rules of procedure. Delimitation of constituencies 17. Delimitation of constituencies. 18. Power of the Election Commission to maintain Delimitation Orders up-to-date. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 19. Amendment of the Scheduled Castes Order. 20. Amendment of the Scheduled Tribes Order. PART IV HIGH COURT 21. High Court of Chhattisgarh. 22. Judges of Chhattisgarh High Court. 23. Jurisdiction of Chhattisgarh High Court. 24. Special provision relating to Bar Council and advocates. 25. Practice and procedure in Chhattisgarh High Court. 26. Custody of seal of Chhattisgarh High Court. 27. Form of writs and other processes. 28. Powers of Judges. 1 SECTIONS 29. Procedure as to appeals to Supreme Court. 30. Transfer of proceedings from Madhya Pradesh High Court to Chhattisgarh High Court. 31. Right to appear or to act in proceedings transferred to Chhattisgarh High Court.