Current Diagnosis and Treatment of Epilepsy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

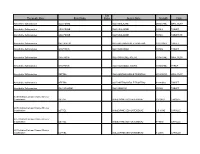

Therapeutic Class Brand Name P a Status Generic

P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 250MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET DR Absorbable Sulfonamides BACTRIM DS SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 800-160MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML SYRUP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 200-40MG/5 ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 400-80MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides SULFADIAZINE SULFADIAZINE 500MG TABLET ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-20MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 2.5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-20MG CAPSULE P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-40MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-40MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 10MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 20MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

1-(4-Amino-Cyclohexyl)

(19) & (11) EP 1 598 339 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 211/04 (2006.01) C07D 211/06 (2006.01) 24.06.2009 Bulletin 2009/26 C07D 235/24 (2006.01) C07D 413/04 (2006.01) C07D 235/26 (2006.01) C07D 401/04 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 05014116.7 C07D 401/06 C07D 403/04 C07D 403/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/44 (2006.01) A61K 31/48 (2006.01) A61K 31/415 (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 18.04.2002 A61K 31/445 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) (54) 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE DERIVATIVES AND RELATED COMPOUNDS AS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGS AND ORL1 LIGANDS FOR THE TREATMENT OF PAIN 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ON DERIVATE UND VERWANDTE VERBINDUNGEN ALS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGE UND ORL1 LIGANDEN ZUR BEHANDLUNG VON SCHMERZ DERIVÉS DE LA 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE ET COMPOSÉS SIMILAIRES POUR L’UTILISATION COMME ANALOGUES DU NOCICEPTIN ET LIGANDES DU ORL1 POUR LE TRAITEMENT DE LA DOULEUR (84) Designated Contracting States: • Victory, Sam AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU Oak Ridge, NC 27310 (US) MC NL PT SE TR • Whitehead, John Designated Extension States: Newtown, PA 18940 (US) AL LT LV MK RO SI (74) Representative: Maiwald, Walter (30) Priority: 18.04.2001 US 284666 P Maiwald Patentanwalts GmbH 18.04.2001 US 284667 P Elisenhof 18.04.2001 US 284668 P Elisenstrasse 3 18.04.2001 US 284669 P 80335 München (DE) (43) Date of publication of application: (56) References cited: 23.11.2005 Bulletin 2005/47 EP-A- 0 636 614 EP-A- 0 990 653 EP-A- 1 142 587 WO-A-00/06545 (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in WO-A-00/08013 WO-A-01/05770 accordance with Art. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/014.3507 A1 Gant Et Al

US 2010.0143507A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/014.3507 A1 Gant et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jun. 10, 2010 (54) CARBOXYLIC ACID INHIBITORS OF Publication Classification HISTONE DEACETYLASE, GABA (51) Int. Cl. TRANSAMINASE AND SODIUM CHANNEL A633/00 (2006.01) A 6LX 3/553 (2006.01) A 6LX 3/553 (2006.01) (75) Inventors: Thomas G. Gant, Carlsbad, CA A63L/352 (2006.01) (US); Sepehr Sarshar, Cardiff by A6II 3/19 (2006.01) the Sea, CA (US) C07C 53/128 (2006.01) A6IP 25/06 (2006.01) A6IP 25/08 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IP 25/18 (2006.01) GLOBAL PATENT GROUP - APX (52) U.S. Cl. .................... 424/722:514/211.13: 514/221; 10411 Clayton Road, Suite 304 514/456; 514/557; 562/512 ST. LOUIS, MO 63131 (US) (57) ABSTRACT Assignee: AUSPEX The present invention relates to new carboxylic acid inhibi (73) tors of histone deacetylase, GABA transaminase, and/or PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., Sodium channel activity, pharmaceutical compositions Vista, CA (US) thereof, and methods of use thereof. (21) Appl. No.: 12/632,507 Formula I (22) Filed: Dec. 7, 2009 Related U.S. Application Data (60) Provisional application No. 61/121,024, filed on Dec. 9, 2008. US 2010/014.3507 A1 Jun. 10, 2010 CARBOXYLIC ACID INHIBITORS OF HISTONE DEACETYLASE, GABA TRANSAMNASE AND SODIUM CHANNEL 0001. This application claims the benefit of priority of Valproic acid U.S. provisional application No. 61/121,024, filed Dec. 9, 2008, the disclosure of which is hereby incorporated by ref 0004 Valproic acid is extensively metabolised via erence as if written herein in its entirety. -

Clinical Review, Adverse Events

Clinical Review, Adverse Events Drug: Carbamazepine NDA: 16-608, Tegretol 20-712, Carbatrol 21-710, Equetro Adverse Event: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Reviewer: Ronald Farkas, MD, PhD Medical Reviewer, DNP, ODE I 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Background Carbamazepine (CBZ) is an anticonvulsant with FDA-approved indications in epilepsy, bipolar disorder and neuropathic pain. CBZ is associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), closely related serious cutaneous adverse drug reactions that can be permanently disabling or fatal. Other anticonvulsants, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, and lamotrigine are also associated with SJS/TEN, as are members of a variety of other drug classes, including nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs and sulfa drugs. The incidence of CBZ-associated SJS/TEN has been considered “extremely rare,” as noted in current U.S. drug labeling. However, recent publications and postmarketing data suggest that CBZ- associated SJS/TEN occurs at a much higher rate in some Asian populations, about 2.5 cases per 1,000 new exposures, and that most of this increased risk is in individuals carrying a specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele, HLA-B*1502. This HLA-B allele is present in about 5- to 20% of many, but not all, Asian populations, and is also present in about 2- to 4% of South Asians/Indians. The allele is also present at a lower frequency, < 1%, in several other ethnic groups around the world (although likely due to distant Asian ancestry). About 10% of U.S. Asians carry HLA-B*1502. HLA-B*1502 is generally not present in the U.S. -

Tegretol (Carbamazepine)

Page 3 Tegretol® carbamazepine USP Chewable Tablets of 100 mg - red-speckled, pink Tablets of 200 mg – pink Suspension of 100 mg/5 mL Tegretol®-XR (carbamazepine extended-release tablets) 100 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg Rx only Prescribing Information WARNING SERIOUS DERMATOLOGIC REACTIONS AND HLA-B*1502 ALLELE SERIOUS AND SOMETIMES FATAL DERMATOLOGIC REACTIONS, INCLUDING TOXIC EPIDERMAL NECROLYSIS (TEN) AND STEVENS-JOHNSON SYNDROME (SJS), HAVE BEEN REPORTED DURING TREATMENT WITH TEGRETOL. THESE REACTIONS ARE ESTIMATED TO OCCUR IN 1 TO 6 PER 10,000 NEW USERS IN COUNTRIES WITH MAINLY CAUCASIAN POPULATIONS, BUT THE RISK IN SOME ASIAN COUNTRIES IS ESTIMATED TO BE ABOUT 10 TIMES HIGHER. STUDIES IN PATIENTS OF CHINESE ANCESTRY HAVE FOUND A STRONG ASSOCIATION BETWEEN THE RISK OF DEVELOPING SJS/TEN AND THE PRESENCE OF HLA-B*1502, AN INHERITED ALLELIC VARIANT OF THE HLA-B GENE. HLA-B*1502 IS FOUND ALMOST EXCLUSIVELY IN PATIENTS WITH ANCESTRY ACROSS BROAD AREAS OF ASIA. PATIENTS WITH ANCESTRY IN GENETICALLY AT- RISK POPULATIONS SHOULD BE SCREENED FOR THE PRESENCE OF HLA-B*1502 PRIOR TO INITIATING TREATMENT WITH TEGRETOL. PATIENTS TESTING POSITIVE FOR THE ALLELE SHOULD NOT BE TREATED WITH TEGRETOL UNLESS THE BENEFIT CLEARLY OUTWEIGHS THE RISK (SEE WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS/LABORATORY TESTS). APLASTIC ANEMIA AND AGRANULOCYTOSIS APLASTIC ANEMIA AND AGRANULOCYTOSIS HAVE BEEN REPORTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE USE OF TEGRETOL. DATA FROM A POPULATION-BASED CASE CONTROL STUDY DEMONSTRATE THAT THE RISK OF DEVELOPING THESE REACTIONS IS 5-8 TIMES GREATER THAN IN THE GENERAL POPULATION. HOWEVER, THE OVERALL RISK OF THESE REACTIONS IN THE UNTREATED GENERAL POPULATION IS LOW, APPROXIMATELY SIX PATIENTS PER ONE MILLION POPULATION PER YEAR FOR AGRANULOCYTOSIS AND TWO PATIENTS PER ONE MILLION POPULATION PER YEAR FOR APLASTIC ANEMIA. -

Non-Opioid Analgesic Definition Regional Any Charge Code Or Professional Fee Associated with Epidural Catheter Placement, Periph

Table S1: Definition of non-opioid analgesics Non-Opioid Analgesic Definition Regional Any charge code or professional fee associated with epidural catheter placement, peripheral nerve block placement or peripheral nerve catheter placement Acetaminophen Any charge for acetaminophen either as a sole agent or in combination with another medication Non-Selective NSAIDs Any code listing choline salicylate, diclofenac, diflunisal, etodolac, fenoprofen, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorketoprofen, ketorolac, meclofenamate, meloxicam , nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin , piroxicam , salsalate, sulindac, tolmetin COX-2 Inhibitors Any code listing celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib Gabapentinoids Any code listing gabapentin, pregabalin Ketamine Any code listing ketamine Table S2: List of ICD-9 codes used to generate covariates Covariate ICD-9 Codes History of Substance Use/Abuse Alcohol abuse 265.2, 291.1–291.3, 291.5–291.9, 303.0, 303.9, 305.0, 357.5, 425.5, 535.3, 571.0–571.3, 980.xx, V11.3 Drug Abuse 292.xx, 304.xx, 305.2–305.9, V65.42 Tobacco Use* 305.1x; V15.82, 649.0x Pain Conditions:* Back Pain 720.xx - 724.xx, 738.4x, 739.3x, 739.4x, 756.11, 756.12, 805.xx, 846.xx, 847.xx, 648.7x Fibromyalgia and or pain 729.1 Migraine or other headache syndrome 346.xx, 339.0x-339.8x; 784.0x Chronic Pain 338.0x (338.1x excluded), 338.2x, 338.4x Rheumatoid Arthritis 714.xx Solid tumor without metastasis 140.xx–172.xx, 174.xx–195.xx Metastatic cancer 196.xx–199.xx Lymphoma 200.xx–202.xx, 203.0, 238.6 Psychiatric Comorbidities Anxiety 300.0x, 300.2x, -

Phenytoin Assay Azide, Preservatives, and Stabilizers

4 REAgENtS Reagents contain the following substances: Mouse monoclonal antibodies reactive to phenytoin (53.4 µg/mL), glucose-6-phosphate (22 mM), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (18 mM), phenytoin labeled with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (0.24 U/mL), Tris buffer, 0.1% sodium Phenytoin Assay azide, preservatives, and stabilizers. Precautions • For in vitro diagnostic use. September 2010 4A152.2D_B • Contains nonsterile mouse monoclonal antibodies. • Assay components contain sodium azide, which may react with lead and copper plumbing See shaded sections: to form highly explosive metal azides. If waste is discarded down the drain, flush it with a Updated information from March 2008 edition. large volume of water to prevent azide buildup. • Do not use the kit after the expiration date. • This kit contains streptomycin sulfate. Please dispose of appropriately. • Turbid or yellow reagents may indicate contamination or degradation and must be discarded. Preparation of Reagents Catalog Quantity/ The Emit® 2000 Phenytoin Assay reagents are provided ready to use; no preparation is Number Product Description Volume necessary. OSR4A229 Emit® 2000 Phenytoin Assay Storage of Assay Components OSR4A518 R1 (Antibody/Substrate Reagent 1) 2 x 21 mL • Improper storage of reagents can affect assay performance. OSR4A548 R2 (Enzyme Reagent 2) 2 x 16 mL • When not in use, store reagents upright at 2–8°C and with screw caps tightly closed. † • Unopened reagents are stable until the expiration date printed on the label if stored upright at 4A109UL Emit® 2000 Phenytoin Calibrators* 1 x 5 mL , 2–8°C. 5 x 2 mL • Do not freeze reagents or expose them to temperatures above 32°C. -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

Australian Statistics on Medicines 1997 Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services

Australian Statistics on Medicines 1997 Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services Australian Statistics on Medicines 1997 i © Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISBN 0 642 36772 8 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be repoduced by any process without written permission from AusInfo. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT 2601. Publication approval number 2446 ii FOREWORD The Australian Statistics on Medicines (ASM) is an annual publication produced by the Drug Utilisation Sub-Committee (DUSC) of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Comprehensive drug utilisation data are required for a number of purposes including pharmacosurveillance and the targeting and evaluation of quality use of medicines initiatives. It is also needed by regulatory and financing authorities and by the Pharmaceutical Industry. A major aim of the ASM has been to put comprehensive and valid statistics on the Australian use of medicines in the public domain to allow access by all interested parties. Publication of the Australian data facilitates international comparisons of drug utilisation profiles, and encourages international collaboration on drug utilisation research particularly in relation to enhancing the quality use of medicines and health outcomes. The data available in the ASM represent estimates of the aggregate community use (non public hospital) of prescription medicines in Australia. In 1997 the estimated number of prescriptions dispensed through community pharmacies was 179 million prescriptions, a level of increase over 1996 of only 0.4% which was less than the increase in population (1.2%). -

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment in 1959

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment in 1959 The two decades between 1938 and 1958 were notable for a large number of new medicinal com- pounds.Phenytoin was of course the most important, but other drugs, some of which are still prescribed, were introduced at this time. Not only drugs – for the ketogenic diet was also popu- larised in this period. Lennox in his book in 1960 gave a long treatise on drug therapy. Head- ing his list were the bromides, which he found rather ineffective, but barbiturates were greeted enthusiastically. Lennox mentioned that 2,500 compounds had been synthesised, and of these 50 compounds were marketed of which phenobarbital was the most frequently used for epilepsy. He was also enthusiastic about phenytoin, especially for patients ‘with long–standing convul- sions previously unrelieved by phenobarbital’ although Mesantoin outranked it on several points, and indeed he favoured their combined use: ‘Mesantoin and Dilantin are Damon and Pythias in respect to their suitability for joint action. Similarity of action gives a doubled therapeutic effect; the dissimilarity of their side reactions keeps these within bounds.’ Phenacemide was ‘what in athletics might be called a triple threat because, more than any other drug, it acts against each of the three main types of seizures, and especially against the most feared psychomotor seizures. However, it is also a triple threat to the patient himself because of possible effect on the marrow, the liver or the psyche.’ Given one chance in 250 of not surviving this treatment, he Drugs introduced into clinical asked, ‘Is the risk too great?’ Trimethadione practice between 1938 and 1958 (Tridione) ‘heads the list of drugs that are 1938 Dilantin Phenytoin peculiarly beneficial to persons subject to 1941 Diamox Acetazolamide 1946 Tridione Trimethadione petits’. -

Drugs Affecting the Central Nervous System

Drugs affecting the central nervous system 15. Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) Epilepsy is caused by the disturbance of the functions of the CNS. Although epileptic seizures have different symptoms, all of them involve the enhanced electric charge of a certain group of central neurons which is spontaneously discharged during the seizure. The instability of the cell membrane potential is responsible for this spontaneous discharge. This instability may result from: increased concentration of stimulating neurotransmitters as compared to inhibiting neurotransmitters decreased membrane potential caused by the disturbance of the level of electrolytes in cells and/or the disturbance of the function of the Na+/K+ pump when energy is insufficient. 2 Mutations in sodium and potassium channels are most common, because they give rise to hyperexcitability and burst firing. Mutations in the sodium channel subunits gene have been associated with - in SCN2A1; benign familial neonatal epilepsy - in SCN1A; severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy - in SCN1A and SCN1B; generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures The potassium channel genes KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 are implicated in some cases of benign familial neonatal epilepsy. Mutations of chloride channels CLCN2 gene have been found to be altered in several cases of classical idiopathic generalized epilepsy suptypes: child-epilepsy and epilepsy with grand mal on awakening. Mutations of calcium channel subunits have been identified in juvenile absence epilepsy (mutation in CACNB4; the B4 subunit of the L-type calcium channel) and idiopathic generalized epilepsy (CACN1A1). 3 Mutations of GABAA receptor subunits also have been detected. The gene encoding the 1 subunit, GABRG1, has been linked to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; mutated GABRG2, encoding an abnormal subunit, has been associated with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures and childhood absence epilepsy.