Antiepileptic Drugs: Evolution of Our Knowledge and Changes in Drug Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

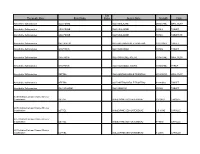

Therapeutic Class Brand Name P a Status Generic

P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 250MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET DR Absorbable Sulfonamides BACTRIM DS SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 800-160MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML SYRUP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 200-40MG/5 ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 400-80MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides SULFADIAZINE SULFADIAZINE 500MG TABLET ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-20MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 2.5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-20MG CAPSULE P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-40MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-40MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 10MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 20MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE -

In Silico Methods for Drug Repositioning and Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

In silico Methods for Drug Repositioning and Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction Pathima Nusrath Hameed ORCID: 0000-0002-8118-9823 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mechanical Engineering THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE May 2018 Copyright © 2018 Pathima Nusrath Hameed All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the author. Abstract Drug repositioning and drug-drug interaction (DDI) prediction are two fundamental ap- plications having a large impact on drug development and clinical care. Drug reposi- tioning aims to identify new uses for existing drugs. Moreover, understanding harmful DDIs is essential to enhance the effects of clinical care. Exploring both therapeutic uses and adverse effects of drugs or a pair of drugs have significant benefits in pharmacology. The use of computational methods to support drug repositioning and DDI prediction en- able improvements in the speed of drug development compared to in vivo and in vitro methods. This thesis investigates the consequences of employing a representative training sam- ple in achieving better performance for DDI classification. The Positive-Unlabeled Learn- ing method introduced in this thesis aims to employ representative positives as well as reliable negatives to train the binary classifier for inferring potential DDIs. Moreover, it explores the importance of a finer-grained similarity metric to represent the pairwise drug similarities. Drug repositioning can be approached by new indication detection. In this study, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification is used as the primary source to determine the indications/therapeutic uses of drugs for drug repositioning. -

Lab Standard Operating Procedures (Sops)

QAPP –Watershed Watch Laboratory Assays Revision: 7 Date: September 2020 Appendix A Standard Operation Procedures List of SOPs SOP SOP Revision Description Number Date General Laboratory Safety 001 11/04 1 URI Laboratory Waste Guidebook 001a 09/13 3 URI laboratory Chemical Hygiene Plan 001b 07/04 Laboratory Water 002 11/16 3 General Labware Cleaning Procedure 003 07/19 4 General Autoclave Operation 004 10/18 6 Bottle Autoclaving Procedure 005 01/16 5 Waste Autoclaving Procedure 006 01/16 3 Chlorophyll-A Analysis, Welschmeyer Method 012 04/18 6 Chloride Analysis 013 11/16 5 Ammonia Analysis 014 11/16 5 Orthophosphate and Nitrate + Nitrite Analysis 015 12/16 5 Total Phosphorus and Nitrogen Analysis 016 12/16 5 Salinity Analysis Using a Refractometer 017 11/16 1 Enterococci Analysis Using Enterolert IDEXX Method 018 12/19 4 Analytical Balance Calibration 019 2/06 2 pH Procedure 021 12/19 3 Alkalinity Procedure 022 11/16 2 Filtering Water Samples 023 10/18 2 Fecal coliform Analysis Using Colilert 18 IDEXX 024 01/16 2 Method Laboratory Thermometer Calibration 025 04/19 1 Heterotrophic Plate Count – Quanti-tray 026 05/20 1 Appendix A Standard Operating Procedure 001 Date: 11/04 General Laboratory Safety Revision: 1 Author: Linda Green University of Rhode Island Watershed Watch 1.0 PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION LAB SAFETY IS EVERYBODY’S JOB! Please be sure to familiarize yourself with these general procedures, as well as the specific handling requirements included in the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for each analysis/process. Further general information regarding University of Rhode Island standards for health and safety are found in SOP 001a – University Safety and Waste Handling Document. -

AHFS Pharmacologic-Therapeutic Classification System

AHFS Pharmacologic-Therapeutic Classification System Abacavir 48:24 - Mucolytic Agents - 382638 8:18.08.20 - HIV Nucleoside and Nucleotide Reverse Acitretin 84:92 - Skin and Mucous Membrane Agents, Abaloparatide 68:24.08 - Parathyroid Agents - 317036 Aclidinium Abatacept 12:08.08 - Antimuscarinics/Antispasmodics - 313022 92:36 - Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drugs - Acrivastine 92:20 - Immunomodulatory Agents - 306003 4:08 - Second Generation Antihistamines - 394040 Abciximab 48:04.08 - Second Generation Antihistamines - 394040 20:12.18 - Platelet-aggregation Inhibitors - 395014 Acyclovir Abemaciclib 8:18.32 - Nucleosides and Nucleotides - 381045 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 317058 84:04.06 - Antivirals - 381036 Abiraterone Adalimumab; -adaz 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 311027 92:36 - Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drugs - AbobotulinumtoxinA 56:92 - GI Drugs, Miscellaneous - 302046 92:20 - Immunomodulatory Agents - 302046 92:92 - Other Miscellaneous Therapeutic Agents - 12:20.92 - Skeletal Muscle Relaxants, Miscellaneous - Adapalene 84:92 - Skin and Mucous Membrane Agents, Acalabrutinib 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 317059 Adefovir Acamprosate 8:18.32 - Nucleosides and Nucleotides - 302036 28:92 - Central Nervous System Agents, Adenosine 24:04.04.24 - Class IV Antiarrhythmics - 304010 Acarbose Adenovirus Vaccine Live Oral 68:20.02 - alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitors - 396015 80:12 - Vaccines - 315016 Acebutolol Ado-Trastuzumab 24:24 - beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents - 387003 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 313041 12:16.08.08 - Selective -

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants INTRODUCTION Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following (Fisher et al 2014): ○ At least 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart; ○ 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; ○ Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. Types of seizures include generalized seizures, focal (partial) seizures, and status epilepticus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018, Epilepsy Foundation 2016). ○ Generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain and include: . Tonic-clonic (grand mal): begin with stiffening of the limbs, followed by jerking of the limbs and face . Myoclonic: characterized by rapid, brief contractions of body muscles, usually on both sides of the body at the same time . Atonic: characterized by abrupt loss of muscle tone; they are also called drop attacks or akinetic seizures and can result in injury due to falls . Absence (petit mal): characterized by brief lapses of awareness, sometimes with staring, that begin and end abruptly; they are more common in children than adults and may be accompanied by brief myoclonic jerking of the eyelids or facial muscles, a loss of muscle tone, or automatisms. ○ Focal seizures are located in just 1 area of the brain and include: . Simple: affect a small part of the brain; can affect movement, sensations, and emotion, without a loss of consciousness . Complex: affect a larger area of the brain than simple focal seizures and the patient loses awareness; episodes typically begin with a blank stare, followed by chewing movements, picking at or fumbling with clothing, mumbling, and performing repeated unorganized movements or wandering; they may also be called “temporal lobe epilepsy” or “psychomotor epilepsy” . -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

1-(4-Amino-Cyclohexyl)

(19) & (11) EP 1 598 339 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 211/04 (2006.01) C07D 211/06 (2006.01) 24.06.2009 Bulletin 2009/26 C07D 235/24 (2006.01) C07D 413/04 (2006.01) C07D 235/26 (2006.01) C07D 401/04 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 05014116.7 C07D 401/06 C07D 403/04 C07D 403/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/44 (2006.01) A61K 31/48 (2006.01) A61K 31/415 (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 18.04.2002 A61K 31/445 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) (54) 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE DERIVATIVES AND RELATED COMPOUNDS AS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGS AND ORL1 LIGANDS FOR THE TREATMENT OF PAIN 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ON DERIVATE UND VERWANDTE VERBINDUNGEN ALS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGE UND ORL1 LIGANDEN ZUR BEHANDLUNG VON SCHMERZ DERIVÉS DE LA 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE ET COMPOSÉS SIMILAIRES POUR L’UTILISATION COMME ANALOGUES DU NOCICEPTIN ET LIGANDES DU ORL1 POUR LE TRAITEMENT DE LA DOULEUR (84) Designated Contracting States: • Victory, Sam AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU Oak Ridge, NC 27310 (US) MC NL PT SE TR • Whitehead, John Designated Extension States: Newtown, PA 18940 (US) AL LT LV MK RO SI (74) Representative: Maiwald, Walter (30) Priority: 18.04.2001 US 284666 P Maiwald Patentanwalts GmbH 18.04.2001 US 284667 P Elisenhof 18.04.2001 US 284668 P Elisenstrasse 3 18.04.2001 US 284669 P 80335 München (DE) (43) Date of publication of application: (56) References cited: 23.11.2005 Bulletin 2005/47 EP-A- 0 636 614 EP-A- 0 990 653 EP-A- 1 142 587 WO-A-00/06545 (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in WO-A-00/08013 WO-A-01/05770 accordance with Art. -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Network-based Drug Repurposing for Novel Coronavirus 2019-nCoV Yadi Zhou1,#, Yuan Hou1,#, Jiayu Shen1, Yin Huang1, William Martin1, Feixiong Cheng1-3,* 1Genomic Medicine Institute, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA 2Department of Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA 3Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA #Equal contribution *Correspondence to: Feixiong Cheng, PhD Lerner Research Institute Cleveland Clinic Tel: +1-216-444-7654; Fax: +1-216-636-0009 Email: [email protected] Supplementary Table S1. Genome information of 15 coronaviruses used for phylogenetic analyses. Supplementary Table S2. Protein sequence identities across 5 protein regions in 15 coronaviruses. Supplementary Table S3. HCoV-associated host proteins with references. Supplementary Table S4. Repurposable drugs predicted by network-based approaches. Supplementary Table S5. Network proximity results for 2,938 drugs against pan-human coronavirus (CoV) and individual CoVs. Supplementary Table S6. Network-predicted drug combinations for all the drug pairs from the top 16 high-confidence repurposable drugs. 1 Supplementary Table S1. Genome information of 15 coronaviruses used for phylogenetic analyses. GenBank ID Coronavirus Identity % Host Location discovered MN908947 2019-nCoV[Wuhan-Hu-1] 100 Human China MN938384 2019-nCoV[HKU-SZ-002a] 99.99 Human China MN975262 -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/014.3507 A1 Gant Et Al

US 2010.0143507A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/014.3507 A1 Gant et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jun. 10, 2010 (54) CARBOXYLIC ACID INHIBITORS OF Publication Classification HISTONE DEACETYLASE, GABA (51) Int. Cl. TRANSAMINASE AND SODIUM CHANNEL A633/00 (2006.01) A 6LX 3/553 (2006.01) A 6LX 3/553 (2006.01) (75) Inventors: Thomas G. Gant, Carlsbad, CA A63L/352 (2006.01) (US); Sepehr Sarshar, Cardiff by A6II 3/19 (2006.01) the Sea, CA (US) C07C 53/128 (2006.01) A6IP 25/06 (2006.01) A6IP 25/08 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IP 25/18 (2006.01) GLOBAL PATENT GROUP - APX (52) U.S. Cl. .................... 424/722:514/211.13: 514/221; 10411 Clayton Road, Suite 304 514/456; 514/557; 562/512 ST. LOUIS, MO 63131 (US) (57) ABSTRACT Assignee: AUSPEX The present invention relates to new carboxylic acid inhibi (73) tors of histone deacetylase, GABA transaminase, and/or PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., Sodium channel activity, pharmaceutical compositions Vista, CA (US) thereof, and methods of use thereof. (21) Appl. No.: 12/632,507 Formula I (22) Filed: Dec. 7, 2009 Related U.S. Application Data (60) Provisional application No. 61/121,024, filed on Dec. 9, 2008. US 2010/014.3507 A1 Jun. 10, 2010 CARBOXYLIC ACID INHIBITORS OF HISTONE DEACETYLASE, GABA TRANSAMNASE AND SODIUM CHANNEL 0001. This application claims the benefit of priority of Valproic acid U.S. provisional application No. 61/121,024, filed Dec. 9, 2008, the disclosure of which is hereby incorporated by ref 0004 Valproic acid is extensively metabolised via erence as if written herein in its entirety. -

Clinical Review, Adverse Events

Clinical Review, Adverse Events Drug: Carbamazepine NDA: 16-608, Tegretol 20-712, Carbatrol 21-710, Equetro Adverse Event: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Reviewer: Ronald Farkas, MD, PhD Medical Reviewer, DNP, ODE I 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Background Carbamazepine (CBZ) is an anticonvulsant with FDA-approved indications in epilepsy, bipolar disorder and neuropathic pain. CBZ is associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), closely related serious cutaneous adverse drug reactions that can be permanently disabling or fatal. Other anticonvulsants, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, and lamotrigine are also associated with SJS/TEN, as are members of a variety of other drug classes, including nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs and sulfa drugs. The incidence of CBZ-associated SJS/TEN has been considered “extremely rare,” as noted in current U.S. drug labeling. However, recent publications and postmarketing data suggest that CBZ- associated SJS/TEN occurs at a much higher rate in some Asian populations, about 2.5 cases per 1,000 new exposures, and that most of this increased risk is in individuals carrying a specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele, HLA-B*1502. This HLA-B allele is present in about 5- to 20% of many, but not all, Asian populations, and is also present in about 2- to 4% of South Asians/Indians. The allele is also present at a lower frequency, < 1%, in several other ethnic groups around the world (although likely due to distant Asian ancestry). About 10% of U.S. Asians carry HLA-B*1502. HLA-B*1502 is generally not present in the U.S. -

Stems for Nonproprietary Drug Names

USAN STEM LIST STEM DEFINITION EXAMPLES -abine (see -arabine, -citabine) -ac anti-inflammatory agents (acetic acid derivatives) bromfenac dexpemedolac -acetam (see -racetam) -adol or analgesics (mixed opiate receptor agonists/ tazadolene -adol- antagonists) spiradolene levonantradol -adox antibacterials (quinoline dioxide derivatives) carbadox -afenone antiarrhythmics (propafenone derivatives) alprafenone diprafenonex -afil PDE5 inhibitors tadalafil -aj- antiarrhythmics (ajmaline derivatives) lorajmine -aldrate antacid aluminum salts magaldrate -algron alpha1 - and alpha2 - adrenoreceptor agonists dabuzalgron -alol combined alpha and beta blockers labetalol medroxalol -amidis antimyloidotics tafamidis -amivir (see -vir) -ampa ionotropic non-NMDA glutamate receptors (AMPA and/or KA receptors) subgroup: -ampanel antagonists becampanel -ampator modulators forampator -anib angiogenesis inhibitors pegaptanib cediranib 1 subgroup: -siranib siRNA bevasiranib -andr- androgens nandrolone -anserin serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonists altanserin tropanserin adatanserin -antel anthelmintics (undefined group) carbantel subgroup: -quantel 2-deoxoparaherquamide A derivatives derquantel -antrone antineoplastics; anthraquinone derivatives pixantrone -apsel P-selectin antagonists torapsel -arabine antineoplastics (arabinofuranosyl derivatives) fazarabine fludarabine aril-, -aril, -aril- antiviral (arildone derivatives) pleconaril arildone fosarilate -arit antirheumatics (lobenzarit type) lobenzarit clobuzarit -arol anticoagulants (dicumarol type) dicumarol -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,357,723 B2 Satyam (45) Date of Patent: Jan

US008357723B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,357,723 B2 Satyam (45) Date of Patent: Jan. 22, 2013 (54) PRODRUGS CONTAINING NOVEL "Nitric Oxide Donors and Cardiovascular Agents Modulating the BO-CLEAVABLE LINKERS Bioactivity of Nitric Oxide: An Overview” by Louis J. Ignarro, et al., Circulation Research, vol. 90, No. 1, pp. 21-22 (Jan. 11, 002). (75) Inventor: Apparao Satyam, Mumbai (IN) “Bis3-(4-substituted phenyl)prop-2-enedisulfides as a new class of (73) Assignee: Piramal Enterprises Limited and antihyperlipidemic compounds' by Meenakshi Sharma, et al., Apparao Satyam, Mumbai (IN) Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Leters, vol. 14, No. 21, pp. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5347-5350 (Nov. 1, 2004). patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Abstract Only "Spectrophotometric determination of binary mix U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. tures of pseudoephedrine with some histamine H1-receptor antago nists using derivative radio spectrum method' by H. Mahgouh, et al., (21) Appl. No.: 12/977,929 J. Pham Biomed Anal, vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 801-809 Mar. 26, 2003. (22) Filed: Dec. 23, 2010 Peter D. Senter et al., Development of Drug-Release Strategy Based (65) Prior Publication Data on the Reductive Fragmentation pf Benzyl Carbamate Disulfides. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1990, 55, 2975-2978. Published by US 2011 FO269709 A1 Nov. 3, 2011 American Chemical Society (USA). Related U.S. Application Data Vivekananda M. Virudhula et al., Reductively Activated Disulfide Prodrugs of Paclitaxel. Biorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, (62) Division of application No. 1 1/213,396, filed on Aug.