********.*****::****A::*************-A***I '************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

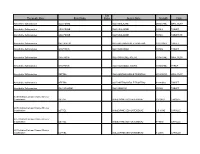

Therapeutic Class Brand Name P a Status Generic

P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 250MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET DR Absorbable Sulfonamides BACTRIM DS SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 800-160MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML SYRUP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 200-40MG/5 ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 400-80MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides SULFADIAZINE SULFADIAZINE 500MG TABLET ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-20MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 2.5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-20MG CAPSULE P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-40MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-40MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 10MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 20MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/0244057 A1 Ehrenberg (43) Pub

US 2011024.4057A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/0244057 A1 Ehrenberg (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 6, 2011 (54) COMBINATION THERAPIES WITH Related U.S. Application Data TOPIRAMATE FOR SEIZURES, RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME, AND OTHER (60) Provisional application No. 61/100,232, filed on Sep. NEUROLOGICAL CONDITIONS 25, 2008. Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventor: Bruce L. Ehrenberg, New York, A633/26 (2006.01) NY (US) A63L/35 (2006.01) A633/06 (2006.01) A6IP 25/00 (2006.01) (21) Appl. No.: 13/120,933 A6IP 25/28 (2006.01) A6IP 25/08 (2006.01) (22) PCT Filed: Sep. 25, 2009 (52) U.S. Cl. .......... 424/648: 514/454; 424/682; 424/646 (57) ABSTRACT (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2009/058495 The invention provides compositions and methods of treating various conditions, including neurological conditions, with S371 (c)(1), pharmaceutical compositions including a sulfamate (e.g., (2), (4) Date: Jun. 9, 2011 topiramate) and magnesium. US 2011/024.4057 A1 Oct. 6, 2011 COMBINATION THERAPES WITH TOPIRAMATE FOR SEIZURES, RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME, AND OTHER II NEUROLOGICAL CONDITIONS CROSS-REFERENCE TO RELATED APPLICATIONS 0001. This application claims the benefit of the priority date of U.S. Application No. 61/100,232, filed Sep. 25, 2008. For the purpose of any U.S. patent that may issue from the 0005 wherein RandR, are the same or different and are U.S. national phase correlate of the present application, the hydrogen, lower alkyl or are alkyl and are joined to form a content of the priority document is hereby incorporated by cyclopentyl or cyclohexyl ring, and (b) magnesium. -

Lab Standard Operating Procedures (Sops)

QAPP –Watershed Watch Laboratory Assays Revision: 7 Date: September 2020 Appendix A Standard Operation Procedures List of SOPs SOP SOP Revision Description Number Date General Laboratory Safety 001 11/04 1 URI Laboratory Waste Guidebook 001a 09/13 3 URI laboratory Chemical Hygiene Plan 001b 07/04 Laboratory Water 002 11/16 3 General Labware Cleaning Procedure 003 07/19 4 General Autoclave Operation 004 10/18 6 Bottle Autoclaving Procedure 005 01/16 5 Waste Autoclaving Procedure 006 01/16 3 Chlorophyll-A Analysis, Welschmeyer Method 012 04/18 6 Chloride Analysis 013 11/16 5 Ammonia Analysis 014 11/16 5 Orthophosphate and Nitrate + Nitrite Analysis 015 12/16 5 Total Phosphorus and Nitrogen Analysis 016 12/16 5 Salinity Analysis Using a Refractometer 017 11/16 1 Enterococci Analysis Using Enterolert IDEXX Method 018 12/19 4 Analytical Balance Calibration 019 2/06 2 pH Procedure 021 12/19 3 Alkalinity Procedure 022 11/16 2 Filtering Water Samples 023 10/18 2 Fecal coliform Analysis Using Colilert 18 IDEXX 024 01/16 2 Method Laboratory Thermometer Calibration 025 04/19 1 Heterotrophic Plate Count – Quanti-tray 026 05/20 1 Appendix A Standard Operating Procedure 001 Date: 11/04 General Laboratory Safety Revision: 1 Author: Linda Green University of Rhode Island Watershed Watch 1.0 PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION LAB SAFETY IS EVERYBODY’S JOB! Please be sure to familiarize yourself with these general procedures, as well as the specific handling requirements included in the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for each analysis/process. Further general information regarding University of Rhode Island standards for health and safety are found in SOP 001a – University Safety and Waste Handling Document. -

AHFS Pharmacologic-Therapeutic Classification System

AHFS Pharmacologic-Therapeutic Classification System Abacavir 48:24 - Mucolytic Agents - 382638 8:18.08.20 - HIV Nucleoside and Nucleotide Reverse Acitretin 84:92 - Skin and Mucous Membrane Agents, Abaloparatide 68:24.08 - Parathyroid Agents - 317036 Aclidinium Abatacept 12:08.08 - Antimuscarinics/Antispasmodics - 313022 92:36 - Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drugs - Acrivastine 92:20 - Immunomodulatory Agents - 306003 4:08 - Second Generation Antihistamines - 394040 Abciximab 48:04.08 - Second Generation Antihistamines - 394040 20:12.18 - Platelet-aggregation Inhibitors - 395014 Acyclovir Abemaciclib 8:18.32 - Nucleosides and Nucleotides - 381045 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 317058 84:04.06 - Antivirals - 381036 Abiraterone Adalimumab; -adaz 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 311027 92:36 - Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drugs - AbobotulinumtoxinA 56:92 - GI Drugs, Miscellaneous - 302046 92:20 - Immunomodulatory Agents - 302046 92:92 - Other Miscellaneous Therapeutic Agents - 12:20.92 - Skeletal Muscle Relaxants, Miscellaneous - Adapalene 84:92 - Skin and Mucous Membrane Agents, Acalabrutinib 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 317059 Adefovir Acamprosate 8:18.32 - Nucleosides and Nucleotides - 302036 28:92 - Central Nervous System Agents, Adenosine 24:04.04.24 - Class IV Antiarrhythmics - 304010 Acarbose Adenovirus Vaccine Live Oral 68:20.02 - alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitors - 396015 80:12 - Vaccines - 315016 Acebutolol Ado-Trastuzumab 24:24 - beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents - 387003 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 313041 12:16.08.08 - Selective -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

1-(4-Amino-Cyclohexyl)

(19) & (11) EP 1 598 339 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 211/04 (2006.01) C07D 211/06 (2006.01) 24.06.2009 Bulletin 2009/26 C07D 235/24 (2006.01) C07D 413/04 (2006.01) C07D 235/26 (2006.01) C07D 401/04 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 05014116.7 C07D 401/06 C07D 403/04 C07D 403/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/44 (2006.01) A61K 31/48 (2006.01) A61K 31/415 (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 18.04.2002 A61K 31/445 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) (54) 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE DERIVATIVES AND RELATED COMPOUNDS AS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGS AND ORL1 LIGANDS FOR THE TREATMENT OF PAIN 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ON DERIVATE UND VERWANDTE VERBINDUNGEN ALS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGE UND ORL1 LIGANDEN ZUR BEHANDLUNG VON SCHMERZ DERIVÉS DE LA 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE ET COMPOSÉS SIMILAIRES POUR L’UTILISATION COMME ANALOGUES DU NOCICEPTIN ET LIGANDES DU ORL1 POUR LE TRAITEMENT DE LA DOULEUR (84) Designated Contracting States: • Victory, Sam AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU Oak Ridge, NC 27310 (US) MC NL PT SE TR • Whitehead, John Designated Extension States: Newtown, PA 18940 (US) AL LT LV MK RO SI (74) Representative: Maiwald, Walter (30) Priority: 18.04.2001 US 284666 P Maiwald Patentanwalts GmbH 18.04.2001 US 284667 P Elisenhof 18.04.2001 US 284668 P Elisenstrasse 3 18.04.2001 US 284669 P 80335 München (DE) (43) Date of publication of application: (56) References cited: 23.11.2005 Bulletin 2005/47 EP-A- 0 636 614 EP-A- 0 990 653 EP-A- 1 142 587 WO-A-00/06545 (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in WO-A-00/08013 WO-A-01/05770 accordance with Art. -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Network-based Drug Repurposing for Novel Coronavirus 2019-nCoV Yadi Zhou1,#, Yuan Hou1,#, Jiayu Shen1, Yin Huang1, William Martin1, Feixiong Cheng1-3,* 1Genomic Medicine Institute, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA 2Department of Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA 3Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA #Equal contribution *Correspondence to: Feixiong Cheng, PhD Lerner Research Institute Cleveland Clinic Tel: +1-216-444-7654; Fax: +1-216-636-0009 Email: [email protected] Supplementary Table S1. Genome information of 15 coronaviruses used for phylogenetic analyses. Supplementary Table S2. Protein sequence identities across 5 protein regions in 15 coronaviruses. Supplementary Table S3. HCoV-associated host proteins with references. Supplementary Table S4. Repurposable drugs predicted by network-based approaches. Supplementary Table S5. Network proximity results for 2,938 drugs against pan-human coronavirus (CoV) and individual CoVs. Supplementary Table S6. Network-predicted drug combinations for all the drug pairs from the top 16 high-confidence repurposable drugs. 1 Supplementary Table S1. Genome information of 15 coronaviruses used for phylogenetic analyses. GenBank ID Coronavirus Identity % Host Location discovered MN908947 2019-nCoV[Wuhan-Hu-1] 100 Human China MN938384 2019-nCoV[HKU-SZ-002a] 99.99 Human China MN975262 -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/014.3507 A1 Gant Et Al

US 2010.0143507A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/014.3507 A1 Gant et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jun. 10, 2010 (54) CARBOXYLIC ACID INHIBITORS OF Publication Classification HISTONE DEACETYLASE, GABA (51) Int. Cl. TRANSAMINASE AND SODIUM CHANNEL A633/00 (2006.01) A 6LX 3/553 (2006.01) A 6LX 3/553 (2006.01) (75) Inventors: Thomas G. Gant, Carlsbad, CA A63L/352 (2006.01) (US); Sepehr Sarshar, Cardiff by A6II 3/19 (2006.01) the Sea, CA (US) C07C 53/128 (2006.01) A6IP 25/06 (2006.01) A6IP 25/08 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IP 25/18 (2006.01) GLOBAL PATENT GROUP - APX (52) U.S. Cl. .................... 424/722:514/211.13: 514/221; 10411 Clayton Road, Suite 304 514/456; 514/557; 562/512 ST. LOUIS, MO 63131 (US) (57) ABSTRACT Assignee: AUSPEX The present invention relates to new carboxylic acid inhibi (73) tors of histone deacetylase, GABA transaminase, and/or PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., Sodium channel activity, pharmaceutical compositions Vista, CA (US) thereof, and methods of use thereof. (21) Appl. No.: 12/632,507 Formula I (22) Filed: Dec. 7, 2009 Related U.S. Application Data (60) Provisional application No. 61/121,024, filed on Dec. 9, 2008. US 2010/014.3507 A1 Jun. 10, 2010 CARBOXYLIC ACID INHIBITORS OF HISTONE DEACETYLASE, GABA TRANSAMNASE AND SODIUM CHANNEL 0001. This application claims the benefit of priority of Valproic acid U.S. provisional application No. 61/121,024, filed Dec. 9, 2008, the disclosure of which is hereby incorporated by ref 0004 Valproic acid is extensively metabolised via erence as if written herein in its entirety. -

Clinical Review, Adverse Events

Clinical Review, Adverse Events Drug: Carbamazepine NDA: 16-608, Tegretol 20-712, Carbatrol 21-710, Equetro Adverse Event: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Reviewer: Ronald Farkas, MD, PhD Medical Reviewer, DNP, ODE I 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Background Carbamazepine (CBZ) is an anticonvulsant with FDA-approved indications in epilepsy, bipolar disorder and neuropathic pain. CBZ is associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), closely related serious cutaneous adverse drug reactions that can be permanently disabling or fatal. Other anticonvulsants, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, and lamotrigine are also associated with SJS/TEN, as are members of a variety of other drug classes, including nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs and sulfa drugs. The incidence of CBZ-associated SJS/TEN has been considered “extremely rare,” as noted in current U.S. drug labeling. However, recent publications and postmarketing data suggest that CBZ- associated SJS/TEN occurs at a much higher rate in some Asian populations, about 2.5 cases per 1,000 new exposures, and that most of this increased risk is in individuals carrying a specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele, HLA-B*1502. This HLA-B allele is present in about 5- to 20% of many, but not all, Asian populations, and is also present in about 2- to 4% of South Asians/Indians. The allele is also present at a lower frequency, < 1%, in several other ethnic groups around the world (although likely due to distant Asian ancestry). About 10% of U.S. Asians carry HLA-B*1502. HLA-B*1502 is generally not present in the U.S. -

Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Antiepileptic Compounds Based on Β-Alanine and Isatin

Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Antiepileptic Compounds Based on β-Alanine and Isatin by Robert Philip Colaguori A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Robert Philip Colaguori, 2016 ii Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Antiepileptic Compounds Based on β-Alanine and Isatin Robert Philip Colaguori Master of Science Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Epilepsy is the fourth-most common neurological disorder in the world. Approximately 70% of cases can be controlled with therapeutics, however 30% remain pharmacoresistant. There is no cure for the disorder, and patients affected are subsequently medicated for life. Thus, there is a need to develop compounds that can treat not only the symptoms, but also delay/prevent progression. Previous work resulted in the discovery of NC-2505, a substituted β-alanine with activity against chemically induced seizures. Several N- and α-substituted derivatives of this compound were synthesized and evaluated in the kindling model and 4-AP model of epilepsy. In the kindling model, RC1-080 and RC1-102 were able to decrease the mean seizure score from 5 to 3 in aged mice. RC1-085 decreased the interevent interval by a factor of 2 in the 4-AP model. Future studies are focused on the synthesis of further compounds to gain insight on structure necessary for activity. iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Donald Weaver for allowing me to join the lab as a graduate student and perform the work ultimately resulting in this thesis. -

Staged Anticonvulsant Screening for Chronic Epilepsy

Staged anticonvulsant screening for chronic epilepsy The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Berdichevsky, Yevgeny, Yero Saponjian, Kyung#Il Park, Bonnie Roach, Wendy Pouliot, Kimberly Lu, Waldemar Swiercz, F. Edward Dudek, and Kevin J. Staley. 2016. “Staged anticonvulsant screening for chronic epilepsy.” Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology 3 (12): 908-923. doi:10.1002/acn3.364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ acn3.364. Published Version doi:10.1002/acn3.364 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:30371039 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA RESEARCH ARTICLE Staged anticonvulsant screening for chronic epilepsy Yevgeny Berdichevsky1,a, Yero Saponjian2,3,a, Kyung-Il Park4,a, Bonnie Roach5, Wendy Pouliot5, Kimberly Lu6, Waldemar Swiercz2,3, F. Edward Dudek5 & Kevin J. Staley2,3 1Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Bioengineering Program, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania 18015 2Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02129 3Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02129 4Department of Neurology, Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center, Seoul, South Korea 06236 5Department of Neurosurgery, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah 84108 6Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 02119 Correspondence Abstract Kevin J. Staley, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA Objective: Current anticonvulsant screening programs are based on seizures 02129. -

Tegretol (Carbamazepine)

Page 3 Tegretol® carbamazepine USP Chewable Tablets of 100 mg - red-speckled, pink Tablets of 200 mg – pink Suspension of 100 mg/5 mL Tegretol®-XR (carbamazepine extended-release tablets) 100 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg Rx only Prescribing Information WARNING SERIOUS DERMATOLOGIC REACTIONS AND HLA-B*1502 ALLELE SERIOUS AND SOMETIMES FATAL DERMATOLOGIC REACTIONS, INCLUDING TOXIC EPIDERMAL NECROLYSIS (TEN) AND STEVENS-JOHNSON SYNDROME (SJS), HAVE BEEN REPORTED DURING TREATMENT WITH TEGRETOL. THESE REACTIONS ARE ESTIMATED TO OCCUR IN 1 TO 6 PER 10,000 NEW USERS IN COUNTRIES WITH MAINLY CAUCASIAN POPULATIONS, BUT THE RISK IN SOME ASIAN COUNTRIES IS ESTIMATED TO BE ABOUT 10 TIMES HIGHER. STUDIES IN PATIENTS OF CHINESE ANCESTRY HAVE FOUND A STRONG ASSOCIATION BETWEEN THE RISK OF DEVELOPING SJS/TEN AND THE PRESENCE OF HLA-B*1502, AN INHERITED ALLELIC VARIANT OF THE HLA-B GENE. HLA-B*1502 IS FOUND ALMOST EXCLUSIVELY IN PATIENTS WITH ANCESTRY ACROSS BROAD AREAS OF ASIA. PATIENTS WITH ANCESTRY IN GENETICALLY AT- RISK POPULATIONS SHOULD BE SCREENED FOR THE PRESENCE OF HLA-B*1502 PRIOR TO INITIATING TREATMENT WITH TEGRETOL. PATIENTS TESTING POSITIVE FOR THE ALLELE SHOULD NOT BE TREATED WITH TEGRETOL UNLESS THE BENEFIT CLEARLY OUTWEIGHS THE RISK (SEE WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS/LABORATORY TESTS). APLASTIC ANEMIA AND AGRANULOCYTOSIS APLASTIC ANEMIA AND AGRANULOCYTOSIS HAVE BEEN REPORTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE USE OF TEGRETOL. DATA FROM A POPULATION-BASED CASE CONTROL STUDY DEMONSTRATE THAT THE RISK OF DEVELOPING THESE REACTIONS IS 5-8 TIMES GREATER THAN IN THE GENERAL POPULATION. HOWEVER, THE OVERALL RISK OF THESE REACTIONS IN THE UNTREATED GENERAL POPULATION IS LOW, APPROXIMATELY SIX PATIENTS PER ONE MILLION POPULATION PER YEAR FOR AGRANULOCYTOSIS AND TWO PATIENTS PER ONE MILLION POPULATION PER YEAR FOR APLASTIC ANEMIA.