Planning Versus Fortification: Sangallo's Project for the Defence of Rome Simon Pepper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allegato Capitolato Tecnico ELENCO STRADE MUN 1

MUN. LOTTO Denominazione strada Note 1A 1 BELVEDERE ANTONIO CEDERNA 1A 1 BELVEDERE TARPEO 1A 1 BORGO ANGELICO 1A 1 BORGO PIO 1A 1 BORGO S. ANGELO 1A 1 BORGO S. LAZZARO 1A 1 BORGO S. SPIRITO 1A 1 BORGO VITTORIO 1A 1 CIRCONVALLAZIONE CLODIA 1A 1 CIRCONVALLAZIONE TRIONFALE 1A 1 CLIVO ARGENTARIO 1A 1 CLIVO DEI PUBLICII 1A 1 CLIVO DELLE MURA VATICANE 1A 1 CLIVO DI ACILIO 1A 1 CLIVO DI ROCCA SAVELLA 1A 1 CLIVO DI SCAURO 1A 1 CLIVO DI VENERE FELICE 1A 1 FORO ROMANO 1A 1 FORO TRAIANO 1A 1 GALLERIA GIOVANNI XXIII 1A 1 GALLERIA PRINCIPE AMEDEO SAVOIA AOSTA 1A 1 GIARDINO DEL QUIRINALE 1A 1 GIARDINO DOMENICO PERTICA 1A 1 GIARDINO FAMIGLIA DI CONSIGLIO 1A 1 GIARDINO GEN. RAFFAELE CADORNA 1A 1 GIARDINO PIETRO LOMBARDI 1A 1 GIARDINO UMBERTO IMPROTA 1A 1 LARGO ANGELICUM 1A 1 LARGO ARRIGO VII 1A 1 LARGO ASCIANGHI 1A 1 LARGO ASSEN PEIKOV 1A 1 LARGO BRUNO BALDINOTTI 1A 1 LARGO CARLO LAZZERINI 1A 1 LARGO CERVINIA 1A 1 LARGO CORRADO RICCI 1A 1 LARGO CRISTINA DI SVEZIA 1A 1 LARGO DEGLI ALICORNI 1A 1 LARGO DEI MUTILATI ED INVALIDI DI GUERRA 1A 1 LARGO DEL COLONNATO 1A 1 LARGO DELLA GANCIA 1A 1 LARGO DELLA POLVERIERA 1A 1 LARGO DELLA SALARA VECCHIA 1A 1 LARGO DELLA SANITA' MILITARE 1A 1 LARGO DELLA SOCIETA' GEOGRAFICA ITALIANA forse parco 1A 1 LARGO DELL'AMBA ARADAM 1A 1 LARGO DELLE TERME DI CARACALLA 1A 1 LARGO DELLE VITTIME DEL TERRORISMO 1A 1 LARGO DI PORTA CASTELLO 1A 1 LARGO DI PORTA S. -

Interpretation of the Function of the Obelisk of Augustus in Rome from Antique Texts to Present Time Virtual Reconstruction

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-2/W11, 2019 GEORES 2019 – 2nd International Conference of Geomatics and Restoration, 8–10 May 2019, Milan, Italy INTERPRETATION OF THE FUNCTION OF THE OBELISK OF AUGUSTUS IN ROME FROM ANTIQUE TEXTS TO PRESENT TIME VIRTUAL RECONSTRUCTION M. Hiermanseder Hietzing Consult, Vienna, Austria - [email protected] KEY WORDS: Astronomy, Line of Meridian, Historical Texts, Archeology, Simulation, Virtual World Heritage ABSTRACT: About the astronomical use of the obelisk of Augustus on Campo Marzio in Rome, which has already been described by Pliny, well known astronomers and mathematicians like Euler, Marinoni or Poleni have given their expert opinion immediately after it's unearthing in 1748. With the prevailing opinion, based on a brief chapter in "Historia naturalis", it would constitute a line of meridian rather than a sundial, the question had been decided for more than 200 years. In 1976, however, the prominent German archeologist Edmund Buchner established once more the assumption, that the obelisk has been part of a gigantic sundial for the apotheosis of the emperor Augustus. Excavations of the German Archeological Institute in 1980/81, which brought to light parts of the inscriptions of the scale, were taken as a proof of his theory by Buchner. Since 1990 works by physicists and experts for chronometry like Schütz, Maes, Auber, et.al., established the interpretation as a line of meridian. Recent measurements and virtual reconstructions of the antique situation in 2013 provide valid evidence for this argument as well. The different approach to the problem mirrors the antagonism between interpretation of antique texts and the assessment of archeological findings in the light of far fledged historical hypotheses. -

Building in Early Medieval Rome, 500-1000 AD

BUILDING IN EARLY MEDIEVAL ROME, 500 - 1000 AD Robert Coates-Stephens PhD, Archaeology Institute of Archaeology, University College London ProQuest Number: 10017236 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10017236 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The thesis concerns the organisation and typology of building construction in Rome during the period 500 - 1000 AD. Part 1 - the organisation - contains three chapters on: ( 1) the finance and administration of building; ( 2 ) the materials of construction; and (3) the workforce (including here architects and architectural tracts). Part 2 - the typology - again contains three chapters on: ( 1) ecclesiastical architecture; ( 2 ) fortifications and aqueducts; and (3) domestic architecture. Using textual sources from the period (papal registers, property deeds, technical tracts and historical works), archaeological data from the Renaissance to the present day, and much new archaeological survey-work carried out in Rome and the surrounding country, I have outlined a new model for the development of architecture in the period. This emphasises the periods directly preceding and succeeding the age of the so-called "Carolingian Renaissance", pointing out new evidence for the architectural activity in these supposed dark ages. -

1 GENERAL 4 February 2020 ENGLISH ONLY OPEN-ENDED

CBD Distr. GENERAL 4 February 2020 ENGLISH ONLY OPEN-ENDED WORKING GROUP ON THE POST- 2020 GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY FRAMEWORK Second meeting 24-29 February 2020 Rome, Italy INFORMATION NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS QUICK LINKS (Control + click on icons for web page, click on page number to directly access text in document) INFORMATION HIGHLIGHTS 1. OFFICIAL OPENING .......................... 2 2. VENUE .............................................. 2 Visa Information (page 5) 3. PRE-REGISTRATION ........................ 3 4. ACCESS TO THE MEETING VENUE AND NAME BADGES .......................... 4 5. MEETING ROOM Meeting Documents (page 4) ALLOCATIONS/RESERVATIONS ....... 4 6. DOCUMENTS .................................... 4 7. GENERAL INFORMATION ON ACCESS TO ROME ............................ 4 8. VISA INFORMATION ......................... 5 Hotel Information (pages 6, 8) 9. SERVICES FOR PARTICIPANTS ........ 5 10. PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL .............. 6 11. SIDE-EVENTS .................................... 6 Weather Information (page 7) 12. HOTEL INFORMATION ..................... 6 ANNEX A - LIST OF HOTELS .......... 8 13. PAYMENT OF THE DAILY SUBSISTENCE ALLOWANCE (DSA) . 6 14. OFFICIAL LANGUAGE ...................... 7 Currency Information (page 7) 15. WEATHER AND TIME ZONE INFORMATION .................................. 7 16. ELECTRICITY ................................... 7 URRENCY 17. C ....................................... 7 18. HEALTH REQUIREMENTS ................ 7 19. DISCLAIMER .................................... 7 1 1. OFFICIAL OPENING -

Qt7hq5t8mm.Pdf

UC Berkeley Room One Thousand Title Water's Pilgrimage in Rome Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hq5t8mm Journal Room One Thousand, 3(3) ISSN 2328-4161 Author Rinne, Katherine Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Katherine Rinne Illustration by Rebecca Sunter Water’s Pilgrimage in Rome “If I were called in To construct a religion I should make use of water.” From Philip Larkin, “Water,” 1964 Rome is one of the world’s most hallowed pilgrimage destinations. Each year, the Eternal City’s numinous qualities draw millions of devout Christians to undertake a pilgrimage there just as they have for nearly two millennia. Visiting the most venerable sites, culminating with St. Peter’s, the Mother Church of Catholicism, the processional journey often reinvigorates faith among believers. It is a cleansing experience for them, a reflective pause in their daily lives and yearly routines. Millions more arrive in Rome with more secular agendas. With equal zeal they set out on touristic, educational, gastronomic, and retail pilgrimages. Indeed, when in Rome, I dedicate at least a full and fervent day to “La Sacra Giornata di Acquistare le Scarpe,” the holy day of shoe shopping, when I visit each of my favorite stores like so many shrines along a sacred way. Although shoes are crucial to our narrative and to the completion of any pilgrimage conducted on Opposite: The Trevi Fountain, 2007. Photo by David Iliff; License: CC-BY-SA 3.0. 27 Katherine Rinne foot, our interest in this essay lies elsewhere, in rededicating Rome’s vital role as a city of reflective pilgrimage by divining water’s hidden course beneath our feet (in shoes, old or new) as it flows out to public fountains in an otherwise parched city. -

Ave Roma Immortalis, Vol. 1, by Francis Marion Crawford This Ebook Is for the Use of Anyone Anywhere at No Cost and with Almost No Restrictions Whatsoever

Roma Immortalis, Vol. 1, by Francis Marion Crawford 1 Roma Immortalis, Vol. 1, by Francis Marion Crawford Project Gutenberg's Ave Roma Immortalis, Vol. 1, by Francis Marion Crawford This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Ave Roma Immortalis, Vol. 1 Studies from the Chronicles of Rome Author: Francis Marion Crawford Release Date: April 26, 2009 [EBook #28614] Language: English Roma Immortalis, Vol. 1, by Francis Marion Crawford 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AVE ROMA IMMORTALIS, VOL. 1 *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. AVE ROMA IMMORTALIS STUDIES FROM THE CHRONICLES OF ROME BY FRANCIS MARION CRAWFORD IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I New York THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., LTD. 1899 All rights reserved Copyright, 1898, By The Macmillan Company. Set up and electrotyped October, 1898. Reprinted November, December, 1898. Norwood Press J. S. Cushing & Co.--Berwick & Smith Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. TABLE OF CONTENTS Roma Immortalis, Vol. 1, by Francis Marion Crawford 3 VOLUME I PAGE THE MAKING OF THE CITY 1 THE EMPIRE 22 THE CITY OF AUGUSTUS 57 THE MIDDLE AGE 78 THE FOURTEEN REGIONS 100 REGION I MONTI 106 REGION II TREVI 155 REGION III COLONNA 190 REGION IV CAMPO MARZO 243 REGION V PONTE 274 REGION VI PARIONE 297 LIST OF PHOTOGRAVURE PLATES VOLUME I Map of Rome Frontispiece FACING PAGE The Wall of Romulus 4 Roma Immortalis, Vol. -

The Streets of Rome Walking Through the Streets of the Capital

Comune di Roma Tourism The streets of Rome Walking through the streets of the capital via dei coronari via giulia via condotti via sistina via del babuino via del portico d’ottavia via dei giubbonari via di campo marzio via dei cestari via dei falegnami/via dei delfini via di monserrato via del governo vecchio via margutta VIA DEI CORONARI as the first thoroughfare to be opened The road, whose fifteenth century charac- W in the medieval city by Pope Sixtus IV teristics have more or less been preserved, as part of preparations for the Great Jubi- passed through two areas adjoining the neigh- lee of 1475, built in order to ensure there bourhood: the “Scortecchiara”, where the was a direct link between the “Ponte” dis- tanners’ premises were to be found, and the trict and the Vatican. The building of the Imago pontis, so called as it included a well- road fell in with Sixtus’ broader plans to known sacred building. The area’s layout, transform the city so as to improve the completed between the fifteenth and six- streets linking the centre concentrated on teenth centuries, and its by now well-es- the Tiber’s left bank, meaning the old Camp tablished link to the city centre as home for Marzio (Campus Martius), with the northern some of its more prominent residents, many regions which had risen up on the other bank, of whose buildings with their painted and es- starting with St. Peter’s Basilica, the idea pecially designed facades look onto the road. being to channel the massive flow of pilgrims The path snaking between the charming and towards Ponte Sant’Angelo, the only ap- shady buildings of via dei Coronari, where proach to the Vatican at that time. -

Curriculum Vitae Europass

Curriculum Vitae Europass Informazioni personali Nome / Cognome ELEONORA SCETTI Telefono ufficio 06.67103856, cell. 339.7838558 E-mail [email protected] Cittadinanza italiana Sesso femminile Esperienza professionale (Presso ROMA CAPITALE) Lavoro o posizione ricoperti - ARCHITETTO, CON POSIZIONE DI RESPONSABILITA’ IN AMBITO ORGANIZZATIVO DI Posizione attuale COMPLESSITA’ ELEVATA, categoria D, p.e. D6O, in servizio presso la Sovrintendenza di Roma Capitale, Direzione Interventi su Edilizia Monumentale, assunta a tempo indeterminato (Contratto di lavoro n. 80 del 16.01.2006). Ruoli ricoperti nella posizione Date Dal 01 giugno 2017 ad oggi Ruolo ricoperto - RESPONSABILE DELL’UFFICIO “Appalti per i beni archeologici, architettonici e monumentali del Suburbio di Roma”, con incarico di alta responsabilita’ ex art. 19 CCDI – Direzione Tecnico Territoriale – Sovrintendenza Capitolina (O.S. n. 60, prot. N. 14695 del 6.06.2017) Dal 01 giugno 2012 al 31 maggio 2017 Date Ruolo ricoperto - TITOLARE DELLA POSIZIONE ORGANIZZATIVA di TIPO “A” con elevata Responsabilità organizzativa/gestionale per il “Coordinamento degli appalti di restauro dei monumenti archeologici, medievali e moderni del Suburbio” della U.O. Monumenti di Roma – Direzione Tecnico Territoriale - Sovrintendenza Capitolina (D. D. Rep. n. S.C. 505 del 31.05.2012) Date Dal 01 agosto 2011 Ruolo ricoperto - RESPONSABIILE DEL PROCESSO ORGANIZZATIVO - UFFICIO DI COORDINAMENTO “Gestione appalti e contabilità” E UFFICIO “Architettura Moderna e contemporanea, incarico di alta responsabilita’ ex art. 19 CCDI vigente – U.O. Tecnica di progettazione, Direzione Tecnico Territoriale – Sovrintendenza Capitolina (O.S. n.125, prot. N. 20051 del 20.09.2011) Date Dal 14 aprile 20 08 al 28 luglio 2011 Ruolo ricoperto - TITOLARE DELLA POSIZIONE ORGANIZZATIVA di TIPO “A” con elevata Responsabilità organizzativa/gestionale per il “Coordinamento, gestione tecnico amministrativa e progettazione degli interventi strategici riguardanti i monumenti medievali e moderni” della U.O. -

The Creative Industry

THE CREATIVE INDUSTRY Regenerating industrial heritage in Rome Maria Nyström Degree project for Master of Science (Two Year) in Conservation 60 HEC Department of Conservation University of Gothenburg 2015:24 THE CREATIVE INDUSTRY Regenerating industrial heritage in Rome Maria Nyström Supervisors: Ola Wetterberg & Krister Olsson Degree project for Master of Science (Two Year) in Conservation 60 HEC Department of Conservation University of Gothenburg 2015 ISSN 1101-33 ISRN GU/KUV--15/24--SE Foreword The work with this master thesis was made possible due to a one-year scholarship at the Swedish Institute of Classical Studies in Rome. This experience allowed me to gain valuable insights into Italian society and access to relevant material. Staying for one year at the institute, I also benefited from the stimulating environment and discussions that were provided – and which came to shape this thesis. I would also like to thank my supervisors Ola Wetterberg and Krister Olsson for their help and support throughout the process of writing this thesis. UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG http://www.conservation.gu.se Department of Conservation Fax +46 31 7864703 P.O. Box 130 Tel +46 31 7864700 SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Master’s Program in Conservation, 120 ects By: Maria Nyström Supervisors: Ola Wetterberg & Krister Olsson The Creative Industry: Regenerating industrial heritage in Rome ABSTRACT Former industries are increasingly being reinterpreted for cultural uses despite sometimes having an ambiguous past. The slaughterhouse in Testaccio, Rome, has since its’ closing in 1975 been the object of various kinds of plans and uses by a number of actors with different interests. -

Via Del Corso La Chiesa Di Santa Maria Di Montesanto RICERCA

Roma- Rione IV Campo Marzio Piazza del Popolo - via del Babuino – via del Corso La Chiesa di Santa Maria di Montesanto RICERCA STORICO ARTISTICA Roma - Rione IV Campo Marzio Piazza del Popolo - via del Babuino – via del Corso La Chiesa di Santa Maria di Montesanto PIANTA DELLA CHIESA DI SANTA MARIA IN MONTESANTO Sulla origine del toponimo “ del popolo “ diverse le spiegazioni. Tra queste quella che il termine derivi dal latino populus in riferimento ad un boschetto di pioppi ed altra che assegna in popolo il significato di parrocchia ed altra ancora che rimanda alla leggenda che narrava dell'esistenza alle falde del Pincio di un noce sotto il quale era sepolto Nerone il cui spettro infastidiva assieme a demoni e streghe i romani. Questi e ed il papa Pasquale II decisero di abbattere l'albero e di gettare le ceneri dell'imperatore nel fiume Tevere. Sul luogo dell'albero fu edificata la cappellina nucleo originario della chiesa di S. Maria che fu quindi costruita a spese del popolo romano da cui la denominazione della chiesa di Santa Maria del Popolo e poi della piazza. Prima della costruzione della chiesa la piazza era detta del trullo da una fontana di questa forma che vi era posta in mezzo. La nascita della piazza coincide con la costruzione delle mura aureliane e della relativa porta Flaminia: fu allora che l'estrema propaggine del Campo Marzio posta tra il Tevere e le pendici del Pincio e attraversata dal primo tratto della via Flaminia venne a far parte della città. Il tridente era già esistente in periodo classico anche se non ancora regolarizzato. -

A Hundred Churches in Rome. an Archival Photogrammetric Project

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-2/W15, 2019 27th CIPA International Symposium “Documenting the past for a better future”, 1–5 September 2019, Ávila, Spain “CENTOCHIESE”: A HUNDRED CHURCHES IN ROME. AN ARCHIVAL PHOTOGRAMMETRIC PROJECT G. Fangi *1, C.Nardinocchi 2, G.Rubeca 2 1Ancona, Italia - [email protected] 2 DICEA, Sapienza University of Rome, 00184 Roma, [email protected], [email protected] Commission II, WG II/8 KEY WORDS: Documentation, Churches, Data Base, Panorama, Spherical Photogrammetry ABSTRACT: Rome is the city where two different cultures have found their greatest architectural achievement, the Latin civilization and the Christian civilization. It is for this reason that in Rome there is the greatest concentration in the world of Roman buildings, monuments and Christian buildings and churches. Rome is the seat of the papacy; say the head of the Christian Church. Every religious order, every Christian nation has created its own headquarters in Rome, the most representative possible, as beautiful, magnificent as possible. The best artists, painters, sculptors, architects, have been called to Rome to create their masterpieces.This study describes the photogrammetric documentation of selected noteworthy churches in Rome. Spherical Photogrammetry is the technique used. The survey is limited to the facades only, being a very significant part of the monument and since no permission is necessary. In certain cases, also the church interior was documented. A total of 170 Churches were surveyed. The statistics that one can derive from such a large number is particularly meaningful. Rome is the ideal place to collect the largest possible number of such cases. -

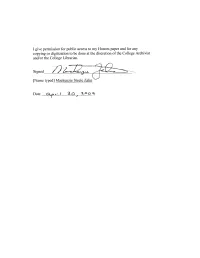

I Give Permission for Public Access to My Honors Paper and for Any

I give permissionfor public accessto my Honorspaper and for any copying or digitizationto be doneat the discretionof the CollegeArchivist and/orthe ColleseLibrarian. fNametyped] MackenzieSteele Zalin Date G-rr.'. 1 30. zoal Monuments of Rome in the Films of Federico Fellini: An Ancient Perspective Mackenzie Steele Zalin Department of Greek and Roman Studies Rhodes College Memphis, Tennessee 2009 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts degree with Honors in Greek and Roman Studies This Honors paper by Mackenzie Steele Zalin has been read and approved for Honors in Greek and Roman Studies. Dr. David H. Sick Project Sponsor Dr. James M. Vest Second Reader Dr. Michelle M. Mattson Extra-Departmental Reader Dr. Kenneth S. Morrell Department Chair Acknowledgments In keeping with the interdisciplinary nature of classical studies as the traditional hallmark of a liberal arts education, I have relied upon sources as vast and varied as the monuments of Rome in writing this thesis. I first wish to extend my most sincere appreciation to the faculty and staff of the Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies in Rome during the spring session of 2008, without whose instruction and inspiration the idea for this study never would have germinated. Among the many scholars who have indelibly influenced my own study, I am particularly indebted to the writings of Catherine Edwards and Mary Jaeger, whose groundbreaking work on Roman topography and monuments in Writing Rome: Textual approaches to the city and Livy’s Written Rome motivated me to apply their theories to a modern context. In order to establish the feasibility and pertinence of comparing Rome’s antiquity to its modernity by examining their prolific juxtapositions in cinema as a case study, I have also relied a great deal upon the works of renowned Italian film scholar, Peter Bondanella, in bridging the ages.