The History of a Riot: Class, Popular Protest and Violence in Early Colonial Nelson Jared Davidson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71 Student Dissertation How to cite: Moore, Wes (2020). The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71. Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71 Wes Moore BA (Hons) Modern History (CNAA) A dissertation submitted to The Open University for the degree of MA in History January 2020 Word count: 15,994 Wes Moore MA Dissertation Abstract This dissertation will analyse what happened to the people of Stoke by Nayland as a result of the migration to New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century. Its time parameters – 1853-71 – are the period of the provincial administration control of migration into New Zealand. The key research questions of this study are: Who migrated to New Zealand during this period and how did the migration affect their life chances? What were the social and economic effects of this migration, particularly on the poorer local families? How did these effects compare with other parish assisted migration in eastern England? Stoke by Nayland in 1851 appears to have been a relatively settled farming community dominated by a few wealthy landowners so emigrants were motivated more by the ‘pull’ of the areas they were moving to than by being ‘pushed’ by high levels of unhappiness ‘at home’. -

Ideas for Using the Prow for Social Studies

Social Science Curriculum Objectives The website, www.theprow.org.nz can help Nelson/Tasman/Marlborough students meet social science objectives in a variety of ways: • Develop research skills • Different levels of information for different abilities and ages • Range of resources including variety of printed material, images, maps and links to web resources • Local stories to which students can relate • Students may have personal connections to stories • Develop writing skills • Project work leading to submitting story to www.theprow.org.nz • Meet curriculum objectives using local stories Below are some suggested Prow stories which may be useful to Social Sciences students -we encourage you to explore the website to look for stories from the top of the South which may fit in with your topics. Social Studies: Level 4 1. Understand how people pass on and sustain culture and heritage for different reasons and that this has consequences for people • Matthew Campbell and his schools • Thomas Cawthron • Thomas Marsden • Suffragettes: Mary Ann Muller and Kate Edger • Te Awatea Hou (top of the South waka) • Maori myths and legends • The World of Wearable Arts 1 2. Understand how exploration and innovation create opportunities and challenges for people, places and environments • Charles Heaphy, Thomas Brunner and Guide Kehu • The Tangata Whenua of te Tau Ihu (the top of the South) • Telegraph made world of difference • Marlborough Aviation • Timber Pioneers + other stories in the Enterprise section • Cawthron Institute 3. Understand that events have causes and effects • Maungatapu Murders • The separation of Nelson and Marlborough • Abel Tasman and Maori in Golden Bay • Wairau Affray 4. -

EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD ; the Coloni- Zation of South Australia and New Zealand

DU ' 422 W2<£ 3 1 M80., fe|^^^H| 11 Ifill H 1 ai 11 finffifflj Hi ijyj kmmil HnnffifffliMB fitMHaiiH! HI HBHi 19 Hi I Jit H Ifufn H 1$Hffli 1 tip jJBffl imnl unit I 1 l;i. I HSSH3 I I .^ *+, -_ %^ ; f f ^ >, c '% <$ Oo >-W aV </> A G°\ ,0O. ,,.^jTR BUILDERS OF GREATER BRITAIN Edited by H. F. WILSON, M.A. Barrister-at-Law Late Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge Legal Assistant at the Colonial Office DEDICATED BY SPECIAL PERMISSION TO HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN BUILDERS OF GREATER BRITAIN i. SIR WALTER RALEGH ; the British Dominion of the West. By Martin A. S. Hume. 2. SIR THOMAS MAITLAND ; the Mastery of the Mediterranean. By Walter Frewen Lord. 3. JOHN AND SEBASTIAN CABOT ; the Discovery of North America. By C. Raymond Beazley, M.A. 4. EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD ; the Coloni- zation of South Australia and New Zealand. By R. Garnett, C.B., LL.D. 5. LORD CLIVE; the Foundation of British Rule in India. By Sir A. J. Arbuthnot, K.C.S.I., CLE. 6. RAJAH BROOKE ; the Englishman as Ruler of an Eastern State. By Sir Spenser St John, G.C.M.G. 7. ADMIRAL PHILLIP ; the Founding of New South Wales. By Louis Becke and Walter Jeffery. 8. SIR STAMFORD RAFFLES; England in the Fnr East. By the Editor. Builders of Greater Britain EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD THE COLONIZATION OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BY •^S R^GARNETT, C.B., LL.D. With Photogravure Frontispiece and Maps NEW YORK LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. -

Extracts of Letters Received by the New Zealand Company 1837-1843 Archives NZ Wellington Reference AAYZ 8977 NZC 18/15 Pages 1-523

Pandora Research www.nzpictures.co.nz Extracts of letters received by the New Zealand Company 1837-1843 Archives NZ Wellington Reference AAYZ 8977 NZC 18/15 pages 1-523 There is no index to this volume of correspondence. Each page is numbered in the top right corner. The following inventory is in chronological order. 1837 Feb 28 Memorial by the late Captain Arthur Wakefield, R.N. to Earl Minto, First Lord of the Admiralty (pages 1-17) 1837 Feb Hythe, Southampton. Captain G. W. Willes (pages 20-21 and p51-52) “These are to certify that Lieutenant Arthur Wakefield served on board HMS ‘Brazen’ under my command from January 1823 to September 1826 when he was appointed by Commander Buller, then on the Coast of Africa, to the Command of the ‘Conflict’ Gun Brig; that his conduct was always that of a most zealous enterprising Officer…” 1836 Feb 14 The Lodge, Ditchingham, Norfolk. Captain Sir Eaton Travers to Lieutenant Wakefield (p29 and p54) 1837 Feb 17 Westbrook St Albans. Captain W. Wellesley to Earl of Minto and given to Lieutenant Wakefield as a testimonial (pages 27-28, 55-56) 1837 Feb 18 Plymouth. Captain W. F. Wise to Earl of Minto and given to Lieutenant Wakefield as a testimonial (pages 24-26 and 57-58) 1837 Feb 22 Greenwich Hospital. Sir Thomas M. Hardy to Lieutenant Wakefield (p23 and p50) 1837 Feb 24 Highbeach. Sir George Cockburn to Lieutenant Wakefield (p22 and 59) 1837 Feb 28 Memorial written by Arthur Wakefield to Earl Minto, First Lord of the Admiralty (pages 30-48) 1837 Mar 10 Southampton. -

(2004) a Sort of Conscience: the Wakefields. by Philip Temple

80 New Zealand Journal of History, 38, 1 (2004) A Sort of Conscience: The Wakefields. By Philip Temple. Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2002. 584 pp. NZ price: $69.95. ISBN 1-86940-276-6. MY FIRST REACTION when asked to review this book was to ask myself, ‘is another book on Edward Gibbon Wakefield (EGW) really necessary, can more be wrung from that proverbial “thrice squeezed orange”?’ And, if so, need the book be of such length? What Philip Temple establishes in A Sort of Conscience is that the answer to these questions must surely be ‘yes’ and ‘yes’. Because here is a ‘panoramic book’ (the publisher’s term) this review will limit itself to its more striking features. First, the underlying argument. While conceding that the lives of almost the whole of the Wakefield family revolved around the career of ‘its most dynamic individual’, EGW himself, Temple believes that, in turn, the career of the great colonial reformer can be explained only when placed in the setting of the collective lives of members of the family. The result is a close consideration of the life story of certain dominating Wakefield figures. We learn of Priscilla, EGW’s radical Quaker grandmother, whose influence spanned generations, of whom hitherto most of us have known nothing. And there is the anatomization of EGW of course, his brothers William and Arthur, and his son Edward Jerningham (Teddy) about each of whom, after reading this book we must admit that we knew far less than we imagined. The Wakefields were a dysfunctional family, although Temple carefully does not introduce this concept until the close of the book lest we prejudge its members. -

New Zealand Hansard Precedent Manual

IND 1 NEW ZEALAND HANSARD PRECEDENT MANUAL Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 2 ABOUT THIS MANUAL The Precedent Manual shows how procedural events in the House appear in the Hansard report. It does not include events in Committee of the whole House on bills; they are covered by the Committee Manual. This manual is concerned with structure and layout rather than text - see the Style File for information on that. NB: The ways in which the House chooses to deal with procedural matters are many and varied. The Precedent Manual might not contain an exact illustration of what you are looking for; you might have to scan several examples and take parts from each of them. The wording within examples may not always apply. The contents of each section and, if applicable, its subsections, are included in CONTENTS at the front of the manual. At the front of each section the CONTENTS lists the examples in that section. Most sections also include box(es) containing background information; these boxes are situated at the front of the section and/or at the front of subsections. The examples appear in a column format. The left-hand column is an illustration of how the event should appear in Hansard; the right-hand column contains a description of it, and further explanation if necessary. At the end is an index. Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 3 INDEX Absence of Minister see Minister not present Amendment/s to motion Abstention/s ..........................................................VOT3-4 Address in reply ....................................................OP12 Acting Minister answers question......................... -

Richard Boast Part 2

In the Waitangi Tribunal Wai 207 Wai 785 Under The Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 In the Matter of The Te Tau Ihu Inquiry (Wai 785) And In the Matter of The claim to the Waitangi Tribunal by Akuhata Wineera, Pirihira Hammond, Ariana Rene, Ruta Rene, Matuaiwi Solomon, Ramari Wineera, Hautonga te Hiko Love, Wikitoria Whatu, Ringi Horomona, Harata Solomon, Rangi Wereta, Tiratu Williams, Ruihi Horomona and Manu Katene for and on behalf of themselves and all descendants of the iwi and hapu of Ngati Toa Rangatira BRIEF OF EVIDENCE OF RICHARD PETER BOAST Part Two: The Wairau, the Cook Strait Crisis of 1843 and the Crown’s Coercion of Ngati Toa 1843 – 1847 Dated 9 June 2003 89 The Terrace PO Box 10246 DX SP26517 Wellington Telephone (04) 472 7877 Facsimile (04) 472 2291 Solicitor Acting: D A Edmunds Counsel: K Bellingham/K E Mitchell/B E Ross 031600235 dae BRIEF OF EVIDENCE OF RICHARD PETER BOAST 1 The Imperial Background in the 1840s 1.1 Introduction: It is important to note the shifts in Crown policy in the 1830s and 1840s, as these shifts had very definite implications for Ngati Toa’s fate. The British Empire was both liberal and coercive. The 1830s was a period when humanitarian concern played an important role in the formation of policy: as Raewyn Dalziel puts it, New Zealand “[came] within the Empire at a moment of liberal humanitarianism”. 1 One key step was the abolition of slavery in 1833 2 (Britain had earlier abolished the slave trade in 1807). 3 Another key step was the parliamentary address to the Crown of July 1834 sponsored by the radical Liberal MP Thomas Fowell Buxton seeking an inquiry into the conditions of indigenous peoples in British possessions. -

The New Zealand Portrait Gallery Exhibition National Archives, Oct- Dec 1997

'THEY PAVED THE WAY' The New Zealand Portrait Gallery Exhibition National Archives, Oct- Dec 1997 'HUGH TEMPLETON OST NEW ZEALAN DERS Portrait ga ll ery has given us a chance this fo unders exhibition? Because it M have sharp memories of to revive memories of our fo unders of shows so much about Wellington, and Wel lin gton; even if they have not the: great age of imperial Britain. Six th e men and women who made this been there: of the capital and its genera ti ons after they established harbour capital of our oddly wonder Parthenon of a Parliament on the H ill; Wel li ngton we have hod time enough fu l cou ntry. This New Zealand Portrait of the Beehive leaning towards that to co ll ect and sift those memories. Gal lery Exhibition of our Wellington monster wooden edifice 'built upon The New Zealand Portrait Gallery founders then is an important event. the sand'; of the curve of Lambton has set up a ve ry professional exhi bi- Largely unnoticed, it deserves wid er Quay, celebrating th e great recogni tion, if not on TV, Lord Durham, of the sharp then as a travelli ng rugged hi ll s overlaid by 'Memories; they cling like cobwebs .. ' exhibition. Bu t who is to Tinakori, once Mt. fund it for the edifica ti on of Wakefield; of popeyed the nation's students? houses stragglin g about the The exhibition stabs at co ntours, and of the night lights ti on We may lack the resources of the visitor with Murray Webb's gli ttering round the great harbour of London's National Portrait Gallery, drawing of that dynamic, far sighted Ta ra. -

Juvenile Travellers: Priscilla Wakefield's Excursions in Empire

1 Juvenile Travellers: Priscilla Wakefield’s Excursions in Empire Ruth Graham While most discussions of juvenile imperial literature relate to the mid-nineteenth century onwards, this article draws attention to an earlier period by examining the children’s books of Priscilla Wakefield. Between 1794 and 1817 Priscilla Wakefield wrote sixteen children’s books that included moral tales, natural history books and a popular travel series. Her experience of the British Empire’s territories was, in the main, derived from the work of others but her use of interesting characters, exciting travel scenarios, the epistolary form to enhance the narrative and fold-out maps, added interest to the information she presented. Her strong personal beliefs are evident throughout her writing and an abhorrence of slavery is a recurring theme. She was also the grandmother and main caregiver of the young Edward Gibbon Wakefield and his immediate siblings. In contrast to his grandmother, Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s experience of the empire was both theoretical and practical. He drew on, and departed from, the work of political economists to develop his theory of systematic colonisation and was active in both Canadian and New Zealand affairs. He began writing about colonisation in the late 1820s and his grandmother’s influence can be seen in his wide use of existing sources and attractive writing style to communicate with his audience. Based on the premise, ‘that juvenile literature acts as an excellent reflector of the dominant ideas of an age’,1 the main focus of this article is to present a study of books of Priscilla Wakefield (née) Bell (1751-1832) to determine the view of the British Empire and its territories that she conveyed to the child reader. -

Samuel Ironside in New Zealand

Samuel Ironside in New Zealand 1 Samuel Ironside in New Zealand First published 1982 RAY RICHARDS PUBLISHER 49 Aberdeen Road, Auckland, New Zealand in association with the Wesley Historical Society of New Zealand 8 Tampin Road, Manurewa, Auckland © Wesley A. Chambers ISBN 0-908596-154 Designed by Don Sinclair Typeset by Linotype Services (P.N.) Ltd Printed and bound by Colorcraft Ltd. 2 Samuel Ironside in New Zealand Contents Dedication Preface by Sir John Marshall Introduction Chapter 1 Sons of Sheffield 2 The Outworking of the Inner Force 3 The Journey Out, 1839 4 Mangungu, 1839-1840 5 Kawhia, 1840 6 Cloudy Bay, Seedbed of the Mission 7 Pioneering in Cloudy Bay, 1840-1843 8 Port Nicholson, 1843-1849 9 Nelson, the Happiest Years in New Zealand 1849-1855 10 New Plymouth 1855-1858 11 Epilogue Appendix 1 The War in New Zealand 2 Wesleyan Missionaries in New Zealand 3 Tributes to Samuel Ironside Bibliography2 3 Samuel Ironside in New Zealand DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF FRANK SMITH JP AND M. A. RUGBY PRATT FR HIST Soc To these two men this book is largely indebted, and gratefully dedicated. Frank Smith had a lifelong interest in Samuel Ironside. As a boy he looked from the veranda of the family home down the length of Port Underwood where Samuel Ironside lived during the short episode of the Cloudy Bay Mission. His farm homestead view looked up to the hill where the victims of the Wairau affray lie buried. Intrigued by the stories of the past, Frank Smith grew to be the man who was the embodiment of Wairau history. -

The Environmental Politics of the Creation of Kahurangi National Park

The Environmental Politics of the Creation of Kahurangi National Park A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Geography by Simon Powrie ~ University of Canterbury 1997 Frontispiece - The Cobb River in Kahurangi National Park. 1 Acknowledgements There are a number of people to thank for their contribution to this thesis: Firstly, thanks to my supervisor Eric. His enthusiasm for the topic and great ideas were greatly appreciated. Thanks also to Aunty Jenny and Peter Perry for keeping my grammar 'proper' and John Thyne for his enormous help with computers. The Masters students for their support and friendship during the last couple of years which was fantastic. Finally, but by no means lastly my family, especially Mum and Dad, for their support and patience during my years at university. 11 111 Abstract This thesis seeks to examine the environmental politics associated with the creation of Kahurangi National Park in 1996. The aims of the thesis are to look at the growth of national parks throughout time and how they have created a platform whereby the Kahurangi landscape became eligible for park status. Conflict of interests regarding Kahurangi occurred, involving many groups who participated in the official investigation process. Also the creation of the park has impacted on the region and this is analysed one year after its creation. The park is explained in the context of the growth of landscape preservation since the nineteenth century. Natural landscape has been treated as a commodity throughout time and preservation must not be seen as a benevolent act of protecting the environment for its own sake, but for human desires and needs. -

State Secrets

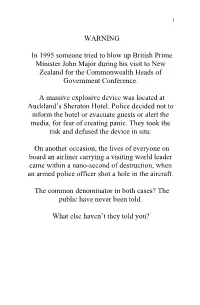

1 WARNING In 1995 someone tried to blow up British Prime Minister John Major during his visit to New Zealand for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Conference. A massive explosive device was located at Auckland’s Sheraton Hotel. Police decided not to inform the hotel or evacuate guests or alert the media, for fear of creating panic. They took the risk and defused the device in situ. On another occasion, the lives of everyone on board an airliner carrying a visiting world leader came within a nano-second of destruction, when an armed police officer shot a hole in the aircraft. The common denominator in both cases? The public have never been told. What else haven’t they told you? 2 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ben Vidgen is a freelance writer/researcher and defence intelligence analyst. His work has been published in New Zealand, Australia and the US. As a researcher he has worked for Canterbury University and a number of corporations and non-profit organisations. State Secrets, his first book, draws on his first hand experience (and the subsequent contacts he developed) within the Royal New Zealand Army, the intelligence community, corporate media and various subcultures within New Zealand. State Secrets also draws upon his academic studies and long term research into intelligence, espionage, terrorism and organised crime. Ben lives in Nelson. He states his hobbies as stand-up comedy and playing in traffic. 3 STate secrets Ben C Vidgen Howling At The Moon Publishing Ltd 4 First edition published 1999 (September) by Howling At The Moon Publishing Ltd, PO Box 302-188 North Harbour Auckland 1310 NEW ZEALAND Email [email protected] Web http://www.howlingatthemoon.com Copyright © Ben Vidgen, 1999 Copyright © Howling At The Moon Publishing Ltd, 1999 The moral rights of the author have been asserted.