Richard Boast Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foton International

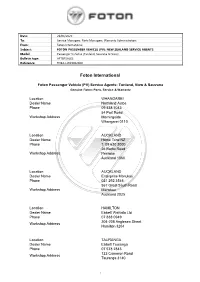

Date: 23/06/2020 To: Service Managers, Parts Managers, Warranty Administrators From: Foton International Subject: FOTON PASSENGER VEHICLE (PV): NEW ZEALAND SERVICE AGENTS Model: Passenger Vehicles (Tunland, Sauvana & View) Bulletin type: AFTERSALES Reference: FDBA-LW23062020 Foton International Foton Passenger Vehicle (PV) Service Agents: Tunland, View & Sauvana Genuine Foton: Parts, Service & Warranty Location WHANGAREI Dealer Name Northland Autos Phone 09 438 7043 54 Port Road Workshop Address Morningside Whangarei 0110 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Home Tune NZ Phone T: 09 630 3000 26 Botha Road Workshop Address Penrose Auckland 1060 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Enterprise Manukau Phone 021 292 3546 567 Great South Road Workshop Address Manukau Auckland 2025 Location HAMILTON Dealer Name Ebbett Waikato Ltd Phone 07 838 0949 204-208 Anglesea Street Workshop Address Hamilton 3204 Location TAURANGA Dealer Name Ebbett Tauranga Phone 07 578 2843 123 Cameron Road Workshop Address Tauranga 3140 1 Location ROTORUA Dealer Name Grant Johnstone Motors Phone 07 349 2221 24-26 Fairy Springs Road Workshop Address Fairy Springs Rotorua 2104 Location TAUPO Dealer Name Central Motor Hub Phone 022 046 5269 79 Miro Street Workshop Address Tauhara Taupo 3330 Location GISBORNE Dealer Name Enterprise Motors Phone 06 867 8368 323 Gladstone Rd Workshop Address Gisborne 4010 Location HASTINGS Dealer Name The Car Company Phone 06 870 9951 909 Karamu Road North Workshop Address Hastings 4122 Location NEW PLYMOUTH Dealer Name Ross Graham Motors Ltd Phone 06 -

Kerikeri Mission House Conservation Plan

MISSION HOUSE Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN i for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Mission House Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN This Conservation Plan was formally adopted by the HNZPT Board 10 August 2017 under section 19 of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014. Report Prepared by CHRIS COCHRAN MNZM, B Arch, FNZIA CONSERVATION ARCHITECT 20 Glenbervie Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand Phone 04-472 8847 Email ccc@clear. net. nz for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Northern Regional Office Premier Buildings 2 Durham Street East AUCKLAND 1010 FINAL 28 July 2017 Deed for the sale of land to the Church Missionary Society, 1819. Hocken Collections, University of Otago, 233a Front cover photo: Kerikeri Mission House, 2009 Back cover photo, detail of James Kemp’s tool chest, held in the house, 2009. ISBN 978–1–877563–29–4 (0nline) Contents PROLOGUES iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Commission 1 1.2 Ownership and Heritage Status 1 1.3 Acknowledgements 2 2.0 HISTORY 3 2.1 History of the Mission House 3 2.2 The Mission House 23 2.3 Chronology 33 2.4 Sources 37 3.0 DESCRIPTION 42 3.1 The Site 42 3.2 Description of the House Today 43 4.0 SIGNIFICANCE 46 4.1 Statement of Significance 46 4.2 Inventory 49 5.0 INFLUENCES ON CONSERVATION 93 5.1 Heritage New Zealand’s Objectives 93 5.2 Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 93 5.3 Resource Management Act 95 5.4 World Heritage Site 97 5.5 Building Act 98 5.6 Appropriate Standards 102 6.0 POLICIES 104 6.1 Background 104 6.2 Policies 107 6.3 Building Implications of the Policies 112 APPENDIX I 113 Icomos New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value APPENDIX II 121 Measured Drawings Prologue The Kerikeri Mission Station, nestled within an ancestral landscape of Ngāpuhi, is the remnant of an invitation by Hongi Hika to Samuel Marsden and Missionaries, thus strengthening the relationship between Ngāpuhi and Pākeha. -

Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/9

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council June 2009 Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council By Barry Robertson and Leigh Stevens Cover Photo: Upper Pauatahanui Arm of Porirua Harbour from mouth of Pautahanui Stream. Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7040, Ph 0275 417 935, 021 417 936, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii Contents Porirua Harbour 2009 - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 4 3. Results and Discussion . 8 4. Conclusions . 15 5. Monitoring ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 6. Management ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 15 8. References ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Appendix 1. Details on Analytical Methods �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Appendix 2. 2009 Detailed Results . 17 Appendix 3. Infauna Characteristics . 23 List of Figures Figure 1. Location of sedimentation and fine scale monitoring -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

REFEREES the Following Are Amongst Those Who Have Acted As Referees During the Production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science

105 REFEREES The following are amongst those who have acted as referees during the production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science. Unfortunately, there are no records listing those who assisted with the first few volumes. Aber, J. (University of Wisconsin, Madison) AboEl-Nil, M. (King Feisal University, Saudi Arabia) Adams, J.A. (Lincoln University, Canterbury) Adams, M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Agren, G. (Swedish University of Agricultural Science, Uppsala) Aitken-Christie, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Allbrook, R. (University of Waikato, Hamilton) Allen, J.D. (University of Canterbury, Christchurch) Allen, R. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Allison, B.J. (Tokoroa) Allison, R.W. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Alma, P.J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Amerson, H.V. (North Carolina State University, Raleigh) Anderson, J.A. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (Telstra, Brisbane) Armitage, I. (NZ Forest Service) Attiwill, P.M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Bachelor, C.L. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Bacon, G. (Queensland Dept of Forestry, Brisbane) Bagnall, R. (NZ Forest Service, Nelson) Bain, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baker, T.G. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Ball, P.R. (Palmerston North) Ballard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bannister, M.H. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baradat, Ph. (Bordeaux) Barr, C. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bartram, D, (Ministry of Forestry, Kaikohe) Bassett, C. (Ngaio, Wellington) Bassett, C. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (NZ Forest Service, Wellington) Baxter, R. (Sittingbourne Research Centre, Kent) Beath, T. (ANM Ltd, Tumut) Beauregard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1): 105-119 (1998) 106 New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1) Beekhuis, J. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71 Student Dissertation How to cite: Moore, Wes (2020). The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71. Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71 Wes Moore BA (Hons) Modern History (CNAA) A dissertation submitted to The Open University for the degree of MA in History January 2020 Word count: 15,994 Wes Moore MA Dissertation Abstract This dissertation will analyse what happened to the people of Stoke by Nayland as a result of the migration to New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century. Its time parameters – 1853-71 – are the period of the provincial administration control of migration into New Zealand. The key research questions of this study are: Who migrated to New Zealand during this period and how did the migration affect their life chances? What were the social and economic effects of this migration, particularly on the poorer local families? How did these effects compare with other parish assisted migration in eastern England? Stoke by Nayland in 1851 appears to have been a relatively settled farming community dominated by a few wealthy landowners so emigrants were motivated more by the ‘pull’ of the areas they were moving to than by being ‘pushed’ by high levels of unhappiness ‘at home’. -

Dougal Austin

Te Hei Tiki A Cultural Continuum DOUGAL AUSTIN TeHeiTiki_TXT_KB6.indd 2-3 29/04/19 8:20 PM He kupu whakataki Introduction 9 01/ Ngā whakamāramatanga Use and meaning 15 02/ Ngā momo me ngā āhua Types and shapes 27 03/ Te pūtakenga mai Physical origins 49 04/ Ngā kōrero kairangi Exalted histories 93 Contents 05/ Ngā tohu ā-iwi Tribal styles 117 06/ Ngā tai whakaawe External versus local influence 139 07/ Ka whiti ka pūmau, 1750–1900 Change and continuity, 1750–1900 153 08/ Te whānako toi taketake, ngā tau 1890–ināianei Cultural appropriation, 1890s–present 185 09/ Te hei tiki me te Māori, 1900–ināianei Māori and hei tiki, 1900–present 199 He kupu whakakapi Epilogue 258 Appendices, Notes, Glossary, Select bibliography, Image credits, Acknowledgements, Index 263 TeHeiTiki_TXT_KB6.indd 6-7 29/04/19 8:20 PM He kupu whakataki Introduction 9 TeHeiTiki_TXT_KB6.indd 8-9 29/04/19 8:20 PM āori personal adornments take a wide variety of forms, all treasured greatly, but without a doubt Mthe human-figure pendants called hei tiki are the most highly esteemed and culturally iconic. This book celebrates the long history of hei tiki and their enduring cultural potency for the Māori people of Aotearoa. Today, these prized pendants are enjoying a resurgence in popularity, part of the late twentieth- to early twenty-first- century revitalisation of Māori culture, which continues to progress from strength to strength. In many ways the story of hei tiki mirrors the changing fortunes of a people, throughout times of prosperity, struggle, adaptation and resilience. -

Mission Film Script-Word

A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing. 8 November 2002, revised April 2016 Sophia (Sophie) Charlotte Rose Jerram PO Box 11 517 Wellington New Zealand i 1 Mission Notes on storv and location This film is set in two locations and in two time zones. It tells a story concerning inter-racial, same-sex love, and the control of imagemaking. A. The past story, 1828-1836 is loosely based on the true story of New Zealand Missionary William Yate and his lover, Eruera Pare Hongi. It is mostly set in Northland, New Zealand, and focuses on the inland Waimate North Mission and surrounding Maori settlement. B. The present day story is a fictional account of Riki Te Awata and an English Photographer, Jeffrey Edison. It is mostly set in the community around a coastal marae and a derelict Southern Mission.1 Sophie Jerram November 2002 1 Unlike the Waimate Mission, this ‘Southern Mission’ is fictional. It was originally intended to be the Puriri mission, at the base of the Coromandel Peninsular, established by William Yate in 1834. Since the coastal mission I have set the film in is nothing like Puriri I have dropped the name. i EXT. PORT JACKSON 1836, DAY A painted image (of the John Gully School) of the historical port of Sydney fills the entire screen. It depicts a number of ships: whaling, convict and trade vessels. The land is busy with diverse groups of people conducting business: traders, convicts, prostitutes, clergymen. -

Henry Tacy's Years at Swanton Morley

This is the Fortieth of an occasional series of articles by David Stone about incidents in the history of Swanton Morley and its church Henry Tacy’s Years at Swanton Morley Introduction In my last article I talked about Henry Tacy’s mission to the Maoris, and in particular about the foundation of a mission station at Kerikeri and the birth there in November 1825 of Henry Tacy Clarke, second son of George Clarke. This was, incidentally, just after Henry Tacy was appointed rector of Swanton Morley. Here, for completeness, I shall tell you a little more about what happened to Henry Tacy’s protégés, James Kemp and George Clarke in New Zealand, before returning to Henry Tacy himself. George Clarke and others decided to build a new mission station and farm at Waimate North, which was not far away from the original station at Kerikeri. However, it required a major effort involving the building of 15 miles of road through rough country, and the bridging of two rivers. The first families moved in in June 1832. Charles Darwin visited the new mission in December 1835, when the Beagle spent 10 days in the Bay of Islands, but overall the mission was not a great success. In 1840 George Clarke reluctantly left the mission when he was appointed by Governor Hobson as ‘Protector of the Maori People’. However, it soon became clear that Clarke was faced with the impossible task both of protecting Maori interests and of acting for the government in land-sale negotiations. He resigned in 1846 and went to live with his son Henry Tacy Clarke at Waimate. -

KIWI BIBLE HEROES Te Pahi

KIWI BIBLE HEROES Te Pahi Te Pahi was one of the most powerful chiefs in the Bay of Islands at the turn of the 19th century. His principal pa was on Te Puna, an Island situated between Rangihoua and Moturoa. He had several wives, five sons and three daughters. Having heard great reports of Governor Phillip King on Norfolk Island, Te Pahi set sail in 1805 with his four sons to meet him. The ship’s master treated Te Pahi and his family poorly during the trip and on arrival decided to retain one of his sons as payments for the journey. To make matters worse, Te Pahi discovered that King had now become the Governor of New South Wales and was no longer on Norfolk Island. Captain Piper, who was now the authority on Norfolk Island, used his powers to rescue Te Pahi and his sons and treated them kindly until the arrival of the Buffalo. Te Pahi and his sons continued their journey to Sydney on the Buffalo in their quest to meet King. In Sydney they were taken to King’s residence where they presented him with gifts from New Zealand. During their stay in Sydney, Te Pahi attended the church at Parramatta conducted by Samuel Marsden. Te Pahi had long conversations with Marsden about spiritual Sources: matters and showed particular interest in the Christian http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1t53/te-pahi accessed May 21, 2014 God. Marsden became impressed with the chief’s Keith Newman, Bible and Treaty, Penguin, 2010 Harris, George Prideaux Robert, 1775-1840 :Tippahee a New Zealand chief / strong, clear mind. -

Ideas for Using the Prow for Social Studies

Social Science Curriculum Objectives The website, www.theprow.org.nz can help Nelson/Tasman/Marlborough students meet social science objectives in a variety of ways: • Develop research skills • Different levels of information for different abilities and ages • Range of resources including variety of printed material, images, maps and links to web resources • Local stories to which students can relate • Students may have personal connections to stories • Develop writing skills • Project work leading to submitting story to www.theprow.org.nz • Meet curriculum objectives using local stories Below are some suggested Prow stories which may be useful to Social Sciences students -we encourage you to explore the website to look for stories from the top of the South which may fit in with your topics. Social Studies: Level 4 1. Understand how people pass on and sustain culture and heritage for different reasons and that this has consequences for people • Matthew Campbell and his schools • Thomas Cawthron • Thomas Marsden • Suffragettes: Mary Ann Muller and Kate Edger • Te Awatea Hou (top of the South waka) • Maori myths and legends • The World of Wearable Arts 1 2. Understand how exploration and innovation create opportunities and challenges for people, places and environments • Charles Heaphy, Thomas Brunner and Guide Kehu • The Tangata Whenua of te Tau Ihu (the top of the South) • Telegraph made world of difference • Marlborough Aviation • Timber Pioneers + other stories in the Enterprise section • Cawthron Institute 3. Understand that events have causes and effects • Maungatapu Murders • The separation of Nelson and Marlborough • Abel Tasman and Maori in Golden Bay • Wairau Affray 4. -

Portraits of Te Rangihaeata

PART IV MR59 103 PART IV MR01 Cootia Pipi Kutia the portrait of cootia at Pitt Rivers Keats’s poem: “Rauparaha stayed on board to dinner, Museum is the first in the Coates sketchbook, and her with his wife, a tall Meg Merrilies-like woman, who husband, Te Rauparaha, is the second. Cootia is more had a bushy head of hair, frizzled out to the height of six commonly known as Kutia or Pipi Kutia. inches all round, and a masculine voice and appetite. Pipi Kutia was wife of Te Rauparaha (MR02), She is the daughter of his last wife by a former husband.”3 acknowledged fighting chief of Ngāti Toa, and of the Tainui–Taranaki alliance. Her mother, Te The New Zealand Company surveyor John Barnicoat Akau, was high-born of the Te Arawa tribe (of the described members of Te Rauparaha’s party in Nelson in Rotorua district of the central North Island of New March 1843: “He has brought three of his wives with him ... Zealand), and her father, Hapekituarangi, was a senior the second ... is a tall stout woman of handsome features hereditary chief of Ngāti Raukawa of Maungatautari if not too masculine ...”4 And the Australian artist (the present-day Cambridge district). Hapekituarangi G. F. Angas, who toured New Zealand in mid to late 1844, was a distant kinsman of Te Rauparaha. On his was also impressed, describing Kutia: deathbed, Hape’s mantle of seniority bypassed his “Rauparaha’s wife is an exceedingly stout woman, and own sons and fell to Te Rauparaha, and in accordance wears her hair, which is very stiff and wiry, combed up with custom, Te Rauparaha married Hape’s widow, into an erect mass upon her head, about a foot in height, Te Akau.1 In c.