Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking in Nayland

The Dedham Vale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty The Dedham Vale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is one of Britain’s finest landscapes. It extends from the Stour estuary in the east to Wormingford in the west. A wider project area extends along the Stour Valley to Walking in the Cambridgeshire border. The AONB was designated in 1970 and covers almost 35 square miles/90 square kms. The outstanding landscape includes ancient woodland, farmland, rivers, meadows and attractive villages. Visiting Constable Country Nayland Ordnance Survey Explorer Map No. 196 Public transport information: (Sudbury, Hadleigh and the Dedham Vale). www.traveline.info or call: 0871 200 22 33 Nayland is located beside the A134 Nayland can be reached by bus or taxi from between Colchester and Sudbury. Colchester Station, which is on the London Nayland Village Hall car park, CO6 4JH Liverpool Street to Norwich main line. (located off Church Lane in Nayland). Train information: www.nationalrail.co.uk or call: 03457 48 49 50 Dedham Vale AONB and Stour Valley Project Email: [email protected] Tel: 01394 445225 Web: www.dedhamvaleandstourvalley.org Walking in nayland Research, text and some photographs by Simon Peachey. Disclaimer: The document reflects the author’s views. The Dedham Vale AONB is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Designed by: Vertas Design & Print Suffolk, December 2017. Design & Print Suffolk, December 2017. Designed by: Vertas The ancient village of Nayland is Discover more of Suffolk’s countryside – walking, cycling and riding leaflets are DISCOVER yours to download for free at Suffolk County Council’s countryside website – surrounded by some of the loveliest www.discoversuffolk.org.uk www.facebook.com/DiscoverSuffolk countryside in the Dedham Vale twitter.com/DiscoverSuffolk port of Sudbury. -

Sudbury - Leavenheath - Nayland - Colchester 84

www.chambersbus.co.uk with effect from 6 September 2017 [email protected] 01206 769778 Sudbury - Leavenheath - Nayland - Colchester 84 Mondays to Fridays 84A Saturdays NSch Sch Sch Long Melford, Bull Lane 0545 . Thomas Gainsborough School (when open) | . 1630 . Sudbury, Bus Station [E] 0555 0655 0915 1030 1200 1330 1500 1500 1500 1640 1730 0715 1015 1315 1615 Sudbury Health Centre 0603 0703 0923 1038 1208 1338 1508 1508 1508 1646 1738 0723 1023 1323 1623 Thomas Gainsborough School | | | | | | | 1520 1520 | | | | | | Newton Green, Church Road 0610 0710 0930 1045 1215 1345 1515 1529 1527 1654 1745 0730 1030 1330 1630 Assington, Shoulder of Mutton 0617 0717 0937 1052 1222 1352 1522 | 1541 1701 1752 0737 1037 1337 1637 Leavenheath, Hare & Hounds 0622 0722 0942 1057 1227 1357 1527 | 1544 1706 1757 0742 1042 1342 1642 Leavenheath, Elm Tree Lane 0625 0726 0946 1101 1231 1401 1531 | 1548 1709 1801 0746 1046 1346 1646 Leavenheath, opp Hare and Hounds, 0629 0730 0950 1105 1235 1405 1535 1542 1546 1713 1805 0750 1050 1350 1650 Leavenheath, Honey Tye | | | | | | | | 1550 | | | | | | Stoke-by-Nayland, The Blundens 0635 0736 0955 1110 1240 1410 1540 1547 . 1718 1810 0755 1055 1355 1655 Stoke-by-Nayland, Village Hall 0637 0738 0957 1112 1242 1412 1542 1549 . 1720 1812 0757 1057 1357 1657 Nayland, Doctors' Surgery 0643 0744 1003 1118 1248 1418 1548 1555 . 1728 1818 0803 1103 1403 1703 Great Horkesley, School Lane 0649 0751 1009 1124 1254 1424 1554 1601 . 1824 0809 1109 1409 1709 Great Horkesley, opp, Half Butt 0652 0754 1012 1127 1257 1427 1557 1604 . -

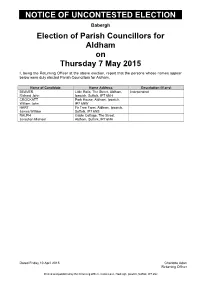

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Aldham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aldham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BEAVER Little Rolls, The Street, Aldham, Independent Richard John Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6NH CROCKATT Park House, Aldham, Ipswich, William John IP7 6NW HART Fir Tree Farm, Aldham, Ipswich, James William Suffolk, IP7 6NS RALPH Gable Cottage, The Street, Jonathan Michael Aldham, Suffolk, IP7 6NH Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Alpheton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alpheton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ARISS Green Apple, Old Bury Road, Alan George Alpheton, Sudbury, CO10 9BT BARRACLOUGH High croft, Old Bury Road, Richard Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BT KEMP Tresco, New Road, Long Melford, Independent Richard Edward Suffolk, CO10 9JY LANKESTER Meadow View Cottage, Bridge Maureen Street, Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BG MASKELL Tye Farm, Alpheton, Sudbury, Graham Ellis Suffolk, CO10 9BL RIX Clapstile Farm, Alpheton, Farmer Trevor William Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BN WATKINS 3 The Glebe, Old Bury Road, Ken Alpheton, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BS Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Assington on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Assington. -

Ideas for Using the Prow for Social Studies

Social Science Curriculum Objectives The website, www.theprow.org.nz can help Nelson/Tasman/Marlborough students meet social science objectives in a variety of ways: • Develop research skills • Different levels of information for different abilities and ages • Range of resources including variety of printed material, images, maps and links to web resources • Local stories to which students can relate • Students may have personal connections to stories • Develop writing skills • Project work leading to submitting story to www.theprow.org.nz • Meet curriculum objectives using local stories Below are some suggested Prow stories which may be useful to Social Sciences students -we encourage you to explore the website to look for stories from the top of the South which may fit in with your topics. Social Studies: Level 4 1. Understand how people pass on and sustain culture and heritage for different reasons and that this has consequences for people • Matthew Campbell and his schools • Thomas Cawthron • Thomas Marsden • Suffragettes: Mary Ann Muller and Kate Edger • Te Awatea Hou (top of the South waka) • Maori myths and legends • The World of Wearable Arts 1 2. Understand how exploration and innovation create opportunities and challenges for people, places and environments • Charles Heaphy, Thomas Brunner and Guide Kehu • The Tangata Whenua of te Tau Ihu (the top of the South) • Telegraph made world of difference • Marlborough Aviation • Timber Pioneers + other stories in the Enterprise section • Cawthron Institute 3. Understand that events have causes and effects • Maungatapu Murders • The separation of Nelson and Marlborough • Abel Tasman and Maori in Golden Bay • Wairau Affray 4. -

BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL BAMBRIDGE HALL, FURTHER STREET ASSINGTON Grid Reference TL 929 397 List Grade II Conservation Area No D

BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL BAMBRIDGE HALL, FURTHER STREET ASSINGTON Grid Reference TL 929 397 List Grade II Conservation Area No Description An important example of a rural workhouse of c.1780, later converted to 4 cottages. Timber framed and plastered with plaintiled roof. 4 external chimney stacks, 3 set against the rear wall and one on the east gable end. C18-C19 windows and doors. The original building contract survives. Suggested Use Residential Risk Priority C Condition Poor Reason for Risk Numerous maintenance failings including areas of missing plaster, missing tiles at rear and defective rainwater goods. First on Register 2006 Owner/Agent Lord and Lady Bambridge Kiddy, Sparrows, Cox Hill, Boxford, Sudbury CO10 5JG Current Availability Not for sale Notes Listed as ‘Farend’. Some render repairs completed and one rear chimney stack rebuilt but work now stalled. Contact Babergh / Mid Suffolk Heritage Team 01473 825852 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL BARN 100M NE OF BENTLEY HALL, BENTLEY HALL ROAD BENTLEY Grid Reference TM 119 385 List Grade II* Conservation Area No Description A large and fine barn of c.1580. Timber-framed, with brick- nogged side walls and brick parapet end gables. The timber frame has 16 bays, 5 of which originally functioned as stables with a loft above (now removed). Suggested Use Contact local authority Risk Priority A Condition Poor Reason for Risk Redundant. Minor slippage of tiles; structural support to one gable end; walls in poor condition and partly overgrown following demolition of abutting buildings. First on Register 2003 Owner/Agent Mr N Ingleton, Ingleton Group, The Old Rectory, School Lane, Stratford St Mary, Colchester CO7 6LZ (01206 321987) Current Availability For sale Notes This is a nationally important site for bats: 7 types use the building. -

Notice of Poll Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for the Election of a COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named County Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The names, in alphabetical order and other particulars of the candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of the persons signing the nomination papers are as follows:- SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS 16 Two Acres Capel St. Mary Frances Blanchette, Lee BUSBY DAVID MICHAEL Liberal Democrats Ipswich IP9 2XP Gifkins CHRISTOPHER Address in the East Suffolk The Conservative Zachary John Norman, Nathan HUDSON GERARD District Party Candidate Callum Wilson 1-2 Bourne Cottages Bourne Hill WADE KEITH RAYMOND Labour Party Tom Loader, Fiona Loader Wherstead Ipswich IP2 8NH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows:- POLLING POLLING STATION DESCRIPTIONS OF PERSONS DISTRICT ENTITLED TO VOTE THEREAT BBEL Belstead Village Hall Grove Hill Belstead IP8 3LU 1.000-184.000 BBST Burstall Village Hall The Street Burstall IP8 3DY 1.000-187.000 BCHA Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-152.000 BCOP Copdock & Washbrook Village Hall London Road Copdock & Washbrook Ipswich IP8 3JN 1.000-915.500 BHIN Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-531.000 BPNN Holiday Inn Ipswich London Road Ipswich IP2 0UA 1.000-2351.000 BPNS Pinewood - Belstead Brook Muthu Hotel Belstead Road Ipswich IP2 9HB 1.000-923.000 BSPR Sproughton - Tithe Barn Lower Street Sproughton IP8 3AA 1.000-1160.000 BWHE Wherstead Village Hall Off The Street Wherstead IP9 2AH 1.000-244.000 5. -

Polstead Hall, Suffolk

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES TEL: 01782 733237 EMAIL: [email protected] LIBRARY Ref code: GB 172 RR M49 Polstead Hall, Suffolk A handlist Librarian: Paul Reynolds Library Telephone: (01782) 733232 Fax: (01782) 734502 Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, United Kingdom Tel: +44(0)1782 732000 http://www.keele.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF KEELE (~istsof Archives) Accession No. or Code: M49 Name and Address University of Keele, Keele, Staffordshire. of Owner: Accumulation or Accumulation of records relating to Polstead Hall, Collection: Suffolk, Raymond Richards Collection of Miscellaneous Historical Material.. (aJohn Rylands Library, Manchester) . Class : Private. Reference Date: Item: Number : DEEDS AND SUPPLEMENTARY MATEXI AL : (i) PLACES SPECIFIED Ashchurch (Glos.) [2nd half Gift, for the service of the donee of 13th and 8/-, of 9 profitable strips of cent. ] land in the field of Northway [in ~shchurch],lying together in the ploughland called 'The Hill1 towards the east, and in length from 'middel- forlung1 towards the waters of 'Karent' (carrant Brook) , paying annually *lb of cumin in 'Theoky' (Tewkesbur~) -' Michaelmas, for all services. (~m~erfect). Parties: (i)William Marshal, son Henry the cordwainer Tewkesbury. (ii)Thomas Cole of North . Witnesses: William Baret, then ba of Tewkeabury, John de 'Gopohull' John de (?) 'Clyna' , Richard Pattk, John Finegal, Henry Cole, Robert Munget, Robert Kelewey, Henry Le Knicht, William de . Stanway. Northway. Quitclaim, of an acre of meadow and 3 acres 15 Aug. of arable land in the vill of Northway, the 14J.5 ownership of which has been the source of controversy between the quitclaimer and the quitclaimee , who successfully claims it on the evidence of a deed of entail. -

Walking in Traditional English Lowland Landscape on the Suffolk-Essex Border

The Stour Valley Picturesque villages, rolling farmland, rivers, meadows, ancient woodlands and a wide variety of local wildlife combine to create what many describe as the Walking in traditional English lowland landscape on the Suffolk-Essex border. The charm of the villages, fascinating local attractions and beauty of the surrounding countryside mean there’s no shortage of places to go and things to see. Visiting Bures & the Stour Valley Ordnance Survey Explorer Map No 196: By Bus - Bures is on the route between Bures Sudbury, Hadleigh and the Dedham Vale. Colchester and Sudbury. Details at www.traveline.info By Car - Bures is on the B1508 between Colchester and Sudbury. By Train – main line London Liverpool Street/Norwich, change at to Marks Tey. There is FREE car parking at the Recreation Bures is on the Marks Tey/Sudbury Ground in Nayland line. Details at www.greateranglia.co.uk Dedham Vale AONB and Stour Valley Project Email: [email protected] Tel: 01394 445225 Web: www.dedhamvalestourvalley.org To Newmarket Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) Local circular walks – free AONB leaflets To Newmarket Stour Valley Project Area Local cycle routes – Stour Valley Path free AONB leaflets Great Bradley To Bury St Edmunds To Bury St Edmunds Country Parks and Picnic sites Public canoe launching locations. Great Bradley Craft must have an appropriate licence To Bury St Edmunds www.riverstourtrust.org To Bury St Edmunds Boxted Boxted To Great Crown copyright. All rights reserved. © Suffolk County Council. Licence LA100023395 -

EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD ; the Coloni- Zation of South Australia and New Zealand

DU ' 422 W2<£ 3 1 M80., fe|^^^H| 11 Ifill H 1 ai 11 finffifflj Hi ijyj kmmil HnnffifffliMB fitMHaiiH! HI HBHi 19 Hi I Jit H Ifufn H 1$Hffli 1 tip jJBffl imnl unit I 1 l;i. I HSSH3 I I .^ *+, -_ %^ ; f f ^ >, c '% <$ Oo >-W aV </> A G°\ ,0O. ,,.^jTR BUILDERS OF GREATER BRITAIN Edited by H. F. WILSON, M.A. Barrister-at-Law Late Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge Legal Assistant at the Colonial Office DEDICATED BY SPECIAL PERMISSION TO HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN BUILDERS OF GREATER BRITAIN i. SIR WALTER RALEGH ; the British Dominion of the West. By Martin A. S. Hume. 2. SIR THOMAS MAITLAND ; the Mastery of the Mediterranean. By Walter Frewen Lord. 3. JOHN AND SEBASTIAN CABOT ; the Discovery of North America. By C. Raymond Beazley, M.A. 4. EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD ; the Coloni- zation of South Australia and New Zealand. By R. Garnett, C.B., LL.D. 5. LORD CLIVE; the Foundation of British Rule in India. By Sir A. J. Arbuthnot, K.C.S.I., CLE. 6. RAJAH BROOKE ; the Englishman as Ruler of an Eastern State. By Sir Spenser St John, G.C.M.G. 7. ADMIRAL PHILLIP ; the Founding of New South Wales. By Louis Becke and Walter Jeffery. 8. SIR STAMFORD RAFFLES; England in the Fnr East. By the Editor. Builders of Greater Britain EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD THE COLONIZATION OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BY •^S R^GARNETT, C.B., LL.D. With Photogravure Frontispiece and Maps NEW YORK LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. -

Extracts of Letters Received by the New Zealand Company 1837-1843 Archives NZ Wellington Reference AAYZ 8977 NZC 18/15 Pages 1-523

Pandora Research www.nzpictures.co.nz Extracts of letters received by the New Zealand Company 1837-1843 Archives NZ Wellington Reference AAYZ 8977 NZC 18/15 pages 1-523 There is no index to this volume of correspondence. Each page is numbered in the top right corner. The following inventory is in chronological order. 1837 Feb 28 Memorial by the late Captain Arthur Wakefield, R.N. to Earl Minto, First Lord of the Admiralty (pages 1-17) 1837 Feb Hythe, Southampton. Captain G. W. Willes (pages 20-21 and p51-52) “These are to certify that Lieutenant Arthur Wakefield served on board HMS ‘Brazen’ under my command from January 1823 to September 1826 when he was appointed by Commander Buller, then on the Coast of Africa, to the Command of the ‘Conflict’ Gun Brig; that his conduct was always that of a most zealous enterprising Officer…” 1836 Feb 14 The Lodge, Ditchingham, Norfolk. Captain Sir Eaton Travers to Lieutenant Wakefield (p29 and p54) 1837 Feb 17 Westbrook St Albans. Captain W. Wellesley to Earl of Minto and given to Lieutenant Wakefield as a testimonial (pages 27-28, 55-56) 1837 Feb 18 Plymouth. Captain W. F. Wise to Earl of Minto and given to Lieutenant Wakefield as a testimonial (pages 24-26 and 57-58) 1837 Feb 22 Greenwich Hospital. Sir Thomas M. Hardy to Lieutenant Wakefield (p23 and p50) 1837 Feb 24 Highbeach. Sir George Cockburn to Lieutenant Wakefield (p22 and 59) 1837 Feb 28 Memorial written by Arthur Wakefield to Earl Minto, First Lord of the Admiralty (pages 30-48) 1837 Mar 10 Southampton. -

(2004) a Sort of Conscience: the Wakefields. by Philip Temple

80 New Zealand Journal of History, 38, 1 (2004) A Sort of Conscience: The Wakefields. By Philip Temple. Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2002. 584 pp. NZ price: $69.95. ISBN 1-86940-276-6. MY FIRST REACTION when asked to review this book was to ask myself, ‘is another book on Edward Gibbon Wakefield (EGW) really necessary, can more be wrung from that proverbial “thrice squeezed orange”?’ And, if so, need the book be of such length? What Philip Temple establishes in A Sort of Conscience is that the answer to these questions must surely be ‘yes’ and ‘yes’. Because here is a ‘panoramic book’ (the publisher’s term) this review will limit itself to its more striking features. First, the underlying argument. While conceding that the lives of almost the whole of the Wakefield family revolved around the career of ‘its most dynamic individual’, EGW himself, Temple believes that, in turn, the career of the great colonial reformer can be explained only when placed in the setting of the collective lives of members of the family. The result is a close consideration of the life story of certain dominating Wakefield figures. We learn of Priscilla, EGW’s radical Quaker grandmother, whose influence spanned generations, of whom hitherto most of us have known nothing. And there is the anatomization of EGW of course, his brothers William and Arthur, and his son Edward Jerningham (Teddy) about each of whom, after reading this book we must admit that we knew far less than we imagined. The Wakefields were a dysfunctional family, although Temple carefully does not introduce this concept until the close of the book lest we prejudge its members. -

The History of a Riot: Class, Popular Protest and Violence in Early Colonial Nelson Jared Davidson

The History of a Riot: Class, Popular Protest and Violence in Early Colonial Nelson Jared Davidson Published by the Labour History Project PO Box 27425, Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand First published in January 2020 ISBN: 978-0-473-51230-9 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Longueville, Sketch of the store in Nelson, New Zealand, 1845. Nelson Provincial Museum, Bett Loan Collection AC804 On Saturday 26 August 1843, pay day for the gang-men employed on the New Zealand Company’s public relief works, acting police magistrate George White frantically prepared for the confrontation to come. Having deployed Nelson’s entire police force to the port and hidden them inside houses surrounding the Company store, White was on his way himself when he was met by a constable in haste. An angry group of 70 to 80 gang- men, armed with guns, clubs and the collective experience of months of continuous conflict, were waiting for him. White sent for reinforcements, hoping the Sheriff could muster up some settlers as special constables. “The generality of the persons however were very reluctant to be sworn in, and some refused.”1 Settlers believed that they too would become objects of attack. Class lines between settlers and labourers had been drawn. In fact, they were there from the beginning. The next hour would not go well for White. Nor was it the first time White, his fellow magistrates and the New Zealand Company officials had confronted the gang-men – agricultural labourers, artisans and their wives who found themselves relying on relief work not dissimilar to schemes administered by the English parishes they had only recently left behind.