Flash Human Rights Report on the Escalation of Fighting in Greater Upper Nile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017 SUDAN Introduction previous REACH assessments of hard-to- presence returned to the averages from April reach areas of Upper Nile State. (22% June, 42% May, 28% April).1 This may Despite a potential respite in fighting in lower MANYO be indicative of the slowing of movement due This Situation Overview outlines displacement counties along the western bank, dispersed to the rainy season. Although fighting that took RENK and access to basic services in Upper Nile fighting and widespread displacements trends place in Panyikang and Fashoda appeared to in June 2017. The first section analyses continued into June and impeded the provision subside, clashes between armed groups armed displacement trends in Upper Nile State. of primary needs and access to basic services groups reportedly commenced in Manyo and The second section outlines the population for assessed settlements. Only 45% of assessed Renk Counties, causing the local population to MELUT dynamics in the assessed settlements, as well settlements reported adequate access to food flee across the border as well as to Renk Town.2 and half reported access to healthcare facilities as access to food and basic services for both FASHODA These clashes may have also contributed to across Upper Nile State, while the malnutrition, MABAN IDP and non-displaced communities. MALAKAL a lack of IDPs, with no assessed settlement malaria and cholera concerns reported in May PANYIKANG BALIET Baliet, Maban, Melut and Renk Counties had in Manyo reporting an IDP presence in June, continued into June. LONGOCHUK less than 5% settlement coverage (Map 1), compared to 50% in May. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an Extension of the Deadline For

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an extension of the deadline for completing the destruction of Anti-personnel Mines in mined areas in accordance with Article 5, paragraph 1 of the convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Antipersonnel Mines and on Their Destruction Submitted at the 18th Meeting of the State Parties Submitted to the Chair of the Committee on Article 5 Implementation Date 31 March 2020 Prepared for State Party: South Sudan Contact Person : Jurkuch Barach Jurkuch Position: Chairperson, NMAA Phone : (211)921651088 Email : [email protected] 1 | Page Contents Abbreviations 3 I. Executive Summary 4 II. Detailed Narrative 8 1 Introduction 8 2 Origin of the Article 5 implementation challenge 8 3 Nature and extent of progress made: Decisions and Recommendations of States Parties 9 4 Nature and extent of progress made: quantitative aspects 9 5 Complications and challenges 16 6 Nature and extent of progress made: qualitative aspects 18 7 Efforts undertaken to ensure the effective exclusion of civilians from mined areas 21 # Anti-Tank mines removed and destroyed 24 # Items of UXO removed and destroyed 24 8 Mine Accidents 25 9 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: quantitative aspects 27 10 The Disaggregation of Current Contamination 30 11 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: qualitative aspects 41 12 Circumstances that impeded compliance during previous extension period 43 12.1 Humanitarian, economic, social and environmental implications of the -

National Education Statistics

2016 NATIONAL EDUCATION STATISTICS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FEBRUARY 2017 www.goss.org © Ministry of General Education & Instruction 2017 Photo Courtesy of UNICEF This publication may be used as a part or as a whole, provided that the MoGEI is acknowledged as the source of information. The map used in this document is not the official maps of the Republic of South Sudan and are for illustrative purposes only. This publication has been produced with financial assistance from the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and technical assistance from Altai Consulting. Soft copies of the complete National and State Education Statistic Booklets, along with the EMIS baseline list of schools and related documents, can be accessed and downloaded at: www.southsudanemis.org. For inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: George Mogga / Director of Planning and Budgeting / MoGEI [email protected] Giir Mabior Cyerdit / EMIS Manager / MoGEI [email protected] Data & Statistics Unit / MoGEI [email protected] Nor Shirin Md. Mokhtar / Chief of Education / UNICEF [email protected] Akshay Sinha / Education Officer / UNICEF [email protected] Daniel Skillings / Project Director / Altai Consulting [email protected] Philibert de Mercey / Senior Methodologist / Altai Consulting [email protected] FOREWORD On behalf of the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), I am delighted to present The National Education Statistics Booklet, 2016, of the Republic of South Sudan (RSS). It is the 9th in a series of publications initiated in 2006, with only one interruption in 2014, a significant achievement for a new nation like South Sudan. The purpose of the booklet is to provide a detailed compilation of statistical information covering key indicators of South Sudan’s education sector, from ECDE to Higher Education. -

South Sudan 2015 Human Rights Report

SOUTH SUDAN 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South Sudan is a republic operating under a transitional constitution signed into law upon declaration of independence from Sudan in 2011. President Salva Kiir Mayardit, whose authority derives from his 2010 election as president of what was then the semiautonomous region of Southern Sudan within the Republic of Sudan, led the country. While the 2010 Sudan-wide elections did not wholly meet international standards, international observers believed Kiir’s election reflected the will of a large majority of Southern Sudanese. International observers considered the 2011 referendum on South Sudanese self-determination, in which 98 percent of voters chose to separate from Sudan, to be free and fair. President Kiir is a founding member of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) political party, the political wing of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Of the 27 ministries, only 21 had appointed ministers in charge, of which 19 are SPLM representatives. The bicameral legislature consists of 332 seats in the National Legislative Assembly (NLA), of which 296 were filled, and 50 seats in the Council of States. SPLM representatives controlled the vast majority of seats in the legislature. Through presidential decrees Kiir replaced eight of the 10 state governors elected since 2010. The constitution states that an election must be held within 60 days if an elected governor has been relieved by presidential decree. This has not happened. The legislature lacked independence, and the ruling party dominated it. Civilian authorities failed at times to maintain effective control over the security forces. In 2013 armed conflict between government and opposition forces began after violence erupted within the Presidential Guard Force (PG) of the SPLA, also known as the Tiger Division. -

C the Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan

C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following persons (from State Ministries of Livestock and Fishery Industries and FAO South Sudan Office) for collecting field data from the sample counties in nine of the ten States of South Sudan: Angelo Kom Agoth; Makuak Chol; Andrea Adup Algoc; Isaac Malak Mading; Tongu James Mark; Sebit Taroyalla Moris; Isaac Odiho; James Chatt Moa; Samuel Ajiing Uguak; Samuel Dook; Rogina Acwil; Raja Awad; Simon Mayar; Deu Lueth Ader; Mayok Dau Wal and John Memur. The authors also extend their special thanks to Erminio Sacco, Chief Technical Advisor and Dr Abdal Monium Osman, Senior Programme Officer, at FAO South Sudan for initiating this study and providing the necessary support during the preparatory and field deployment phases. DISCLAIMER FAO South Sudan mobilized a team of independent consultants to conduct this study. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. COMPOSITION OF STUDY TEAM Yacob Aklilu Gebreyes (Team Leader) Gezu Bekele Lemma Luka Biong Deng Shaif Abdullahi i C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...I ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... VI NOTES .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Peace Is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp By

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT PEACE IS THE NAME OF OUR CATTLE-CAMP LOCAL RESPONSES TO CONFLICT IN EASTERN LAKES STATE, SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT Peace is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local responses to conflict in Eastern Lakes State, South Sudan JOHN RYLE AND MACHOT AMUOM Authors John Ryle (co-author), Legrand Ramsey Professor of Anthropology at Bard College, New York, was born and educated in the United Kingdom. He is lead researcher on the RVI South Sudan Customary Authorities Project. Machot Amuom Malou (co-author) grew up in Yirol during Sudan’s second civil war. He is a graduate of St. Lawrence University, Uganda, and a member of The Greater Yirol Youth Union that organised the 2010 Yirol Peace Conference. Abraham Mou Magok (research consultant) is a graduate of the Nile Institute of Management Studies in Uganda. Born in Aluakluak, he has worked in local government and the NGO sector in Greater Yirol. Aya piŋ ëë kͻcc ἅ luël toc ku wεl Ɣͻk Ɣͻk kuek jieŋ ku Atuot akec kaŋ thör wal yic Yeŋu ye köc röt nͻk wεt toc ku wal Mith thii nhiar tͻͻŋ ku ran wut pεεc Yin aci pεεc tik riεl Acin ke cam riεlic Kͻcdit nyiar tͻͻŋ Ku cͻk ran nͻk aci yͻk thin Acin ke cam riεlic Wut jiëŋ ci riͻc Wut Atuot ci riͻc Yok Ɣen Apaak ci riͻc Yen ya wutdie Acin kee cam riεlic ëëë I hear people are fighting over grazing land. Cattle don’t fight—neither Jieŋ cattle nor Atuot cattle. Why do we fight in the name of grass? Young men who raid cattle-camps— You won’t get a wife that way. -

Bentiu and Malakal Poc Sites’

Conflict Sensitivity Analysis: United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Protection of Civilian (PoC) Sites Transition: Bentiu, Unity State, and Malakal, Upper Nile State Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility March 2021 This Conflict Sensitivity Analysis (CSA) was requested by the Inter-Cluster Coordination Group in October 2020 and examines the conflict sensitivity implications of the transition of UN Protection of Civilian sites in Bentiu, Unity State, and Malakal, Upper Nile State, from sites under the protection of United Nations Mission in South Sudan to camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) under the jurisdiction of the Government of the Republic of South Sudan. The Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility is intended to support conflict-sensitive aid programming in South Sudan. The Facility is funded by the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Canadian donor missions in South Sudan and is implemented by a consortium of NGOs including Saferworld and swisspeace. Conflict Sensitivity Analysis: Malakal and Bentiu PoC sites Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... i 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Overview ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Politics, Power and Chiefship in Famine and War a Study Of

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT POLITICS, POWER AND CHIEFSHIP IN FAMINE AND WAR A STUDY OF THE FORMER NORTHERN BAHR el-ghazal STATE, SOUTH SUDAN RIfT vAllEY INSTITUTE SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities Politics, power and chiefship in famine and war A study of the former Northern Bahr el-Ghazal state, South Sudan NICKI KINDERSLEY Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHOR Nicki Kindersley is a historian of the Sudans. She is currently Harry F. Guggenheim Research Fellow at Pembroke College, Cambridge University, and a Director of Studies on the RVI Sudan and South Sudan Course. THE RESEARCH TEAM The research was designed and conducted with co-researcher Joseph Diing Majok and research assistant Paulino Dhieu Tem. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES (SSCA) PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH & COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PROGRAMME MANAGER: Tymon Kiepe EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-54-8 COVER: A chiefs’ meeting in Malualkon in Aweil East, South Sudan. RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2017 Cover image © Nicki Kindersley Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

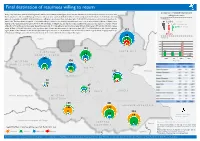

Final Destination of Returnees Willing to Return

Final destination of returnees willing to return Comparison of Stranded Returnees and A key component of the Renk biometric registration exercise is to establish the willingness of the stranded returnees to receive transport assistance to move to their willingness to return final destination. To this end, individuals aged 15 years and above were asked about their intention to return and planned final destination in South Sudan. The data gathered demonstrates that 48.2% (2,841individuals) are willing to return to their final destination, while 51.8% (3,057 individuals) do not intend to depart from the OVERALL transit sites. This map shows the number of individuals willing to return, broken down by state and transit site. It can be inferred that population of Payuer site is 5,898 Total Stranded heading to the Greater Equatoria region (96.1% or 976 individuals). In Abayok site, the majority of the population has expressed the intention to remain in Renk, 3,057 Not willing to return while only 12.9% wish to go to the Greater Upper Nile region and 11.4% are willing to return to the Greater Bahr el Ghazal region (479 and 422 individuals, respec- 2,841 Willing to return tively). In Mina, 99.7% (860 individuals) of the population aged 15 years and above intend to depart from Renk (42.1% or 363 individuals to the Greater Equatoria region, 42.4% or 366 individuals to the Greater Upper Nile region, and 15.2% or 131 individuals to the Greater Bahr el Ghazal region). Finally, in Agany only 6.9% (21 327 individuals) are willing to proceed to their final destination, all to counties within the Greater Upper Nile region.