Everyone and Everything Is a Target

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017 SUDAN Introduction previous REACH assessments of hard-to- presence returned to the averages from April reach areas of Upper Nile State. (22% June, 42% May, 28% April).1 This may Despite a potential respite in fighting in lower MANYO be indicative of the slowing of movement due This Situation Overview outlines displacement counties along the western bank, dispersed to the rainy season. Although fighting that took RENK and access to basic services in Upper Nile fighting and widespread displacements trends place in Panyikang and Fashoda appeared to in June 2017. The first section analyses continued into June and impeded the provision subside, clashes between armed groups armed displacement trends in Upper Nile State. of primary needs and access to basic services groups reportedly commenced in Manyo and The second section outlines the population for assessed settlements. Only 45% of assessed Renk Counties, causing the local population to MELUT dynamics in the assessed settlements, as well settlements reported adequate access to food flee across the border as well as to Renk Town.2 and half reported access to healthcare facilities as access to food and basic services for both FASHODA These clashes may have also contributed to across Upper Nile State, while the malnutrition, MABAN IDP and non-displaced communities. MALAKAL a lack of IDPs, with no assessed settlement malaria and cholera concerns reported in May PANYIKANG BALIET Baliet, Maban, Melut and Renk Counties had in Manyo reporting an IDP presence in June, continued into June. LONGOCHUK less than 5% settlement coverage (Map 1), compared to 50% in May. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an Extension of the Deadline For

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an extension of the deadline for completing the destruction of Anti-personnel Mines in mined areas in accordance with Article 5, paragraph 1 of the convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Antipersonnel Mines and on Their Destruction Submitted at the 18th Meeting of the State Parties Submitted to the Chair of the Committee on Article 5 Implementation Date 31 March 2020 Prepared for State Party: South Sudan Contact Person : Jurkuch Barach Jurkuch Position: Chairperson, NMAA Phone : (211)921651088 Email : [email protected] 1 | Page Contents Abbreviations 3 I. Executive Summary 4 II. Detailed Narrative 8 1 Introduction 8 2 Origin of the Article 5 implementation challenge 8 3 Nature and extent of progress made: Decisions and Recommendations of States Parties 9 4 Nature and extent of progress made: quantitative aspects 9 5 Complications and challenges 16 6 Nature and extent of progress made: qualitative aspects 18 7 Efforts undertaken to ensure the effective exclusion of civilians from mined areas 21 # Anti-Tank mines removed and destroyed 24 # Items of UXO removed and destroyed 24 8 Mine Accidents 25 9 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: quantitative aspects 27 10 The Disaggregation of Current Contamination 30 11 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: qualitative aspects 41 12 Circumstances that impeded compliance during previous extension period 43 12.1 Humanitarian, economic, social and environmental implications of the -

National Education Statistics

2016 NATIONAL EDUCATION STATISTICS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FEBRUARY 2017 www.goss.org © Ministry of General Education & Instruction 2017 Photo Courtesy of UNICEF This publication may be used as a part or as a whole, provided that the MoGEI is acknowledged as the source of information. The map used in this document is not the official maps of the Republic of South Sudan and are for illustrative purposes only. This publication has been produced with financial assistance from the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and technical assistance from Altai Consulting. Soft copies of the complete National and State Education Statistic Booklets, along with the EMIS baseline list of schools and related documents, can be accessed and downloaded at: www.southsudanemis.org. For inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: George Mogga / Director of Planning and Budgeting / MoGEI [email protected] Giir Mabior Cyerdit / EMIS Manager / MoGEI [email protected] Data & Statistics Unit / MoGEI [email protected] Nor Shirin Md. Mokhtar / Chief of Education / UNICEF [email protected] Akshay Sinha / Education Officer / UNICEF [email protected] Daniel Skillings / Project Director / Altai Consulting [email protected] Philibert de Mercey / Senior Methodologist / Altai Consulting [email protected] FOREWORD On behalf of the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), I am delighted to present The National Education Statistics Booklet, 2016, of the Republic of South Sudan (RSS). It is the 9th in a series of publications initiated in 2006, with only one interruption in 2014, a significant achievement for a new nation like South Sudan. The purpose of the booklet is to provide a detailed compilation of statistical information covering key indicators of South Sudan’s education sector, from ECDE to Higher Education. -

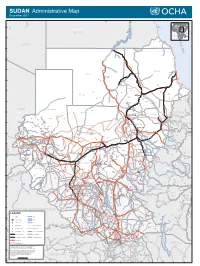

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

PRESS RELEASE Marina Modi Public &Media Relations Officer [email protected] 0955950026 #Defyhatenow: Mobilizing Civic A

PRESS RELEASE Marina Modi Public &Media relations Officer [email protected] 0955950026 #defyhatenow: Mobilizing Civic Action against Hate Speech and Directed Social Media Incitement to Violence in South Sudan. Juba, 03 November 2017 #DEFYHATENOW WIKIPEDIA WORKSHOP #defyhatenow initiative will be training students from the University of Juba on writing and feeding /editing information about South Sudan on Wikipedia,the online global encyclopedia from 6- 9 November 2017. Objectives; 1. Empowering South Sudanese to have a global voice in national narratives and knowledge in the quest for lasting peace. 2. Generating more knowledge about other people-to-people peace-building issues. 3. Initiate a sustainable movement of South Sudanese Wikipedia writers/editors. Why Wikipedia? South Sudan is underrepresented at Wikipedia, the world's largest online encyclopedia. There are hardly 1.500 articles about South Sudanese subjects and most of them are just stubs, since even entries about many major towns and states only feature a couple of lines. While Wikipedia is one of the most used and visited websites, next to no content about South Sudan has been generated inside the country itself. Instead, most information about South Sudan has been created by outsiders. With regard to internal peace-making, #defyhatenow will be working with the student run #kefkum initiative to collaboratively edit, starting with a critical review of Wunlit conference and then create a comprehensive article on Wikipedia. As a pilot example, #defyhatenow has already edited the Wikipedia article about Deim Zubeir from a one-line stub to a multi-facetted overview. Deim Zubeir has recently been included on South Sudan's first tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage sites. -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 March 8, 2019

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 MARCH 8, 2019 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Insecurity in Yei results in unknown number of civilian deaths, prevents 15,000 5% 7% 20% people from receiving aid 7.1 million 7% Estimated People in South Health actors continue EVD awareness Sudan Requiring Humanitarian 10% and screening activities Assistance 19% 2019 Humanitarian Response Plan – WFP conducts first road delivery to 15% December 2018 central Unity 17% Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Health (17%) 6.5 million FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE Nutrition (15%) Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) February 2019 Shelter & Settlements (5%) USAID/FFP $398,226,647 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 1.9 million USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $624,967,8824 Estimated IDPs in BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE South Sudan SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 UN – January 31, 2019 84% 9% 5% U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,756,094,855 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE 191,238 Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases UNMISS – March 4, 2019 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Ongoing violence between Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GoRSS) and opposition forces near Central Equatoria State’s Yei area has displaced an estimated 2.3 million 7,400 people to Yei town since December and is preventing relief agencies from reaching Estimated Refugees and Asylum more than 15,000 additional people seeking safety outside of Yei, the UN reports. -

South Sudan 2015 Human Rights Report

SOUTH SUDAN 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South Sudan is a republic operating under a transitional constitution signed into law upon declaration of independence from Sudan in 2011. President Salva Kiir Mayardit, whose authority derives from his 2010 election as president of what was then the semiautonomous region of Southern Sudan within the Republic of Sudan, led the country. While the 2010 Sudan-wide elections did not wholly meet international standards, international observers believed Kiir’s election reflected the will of a large majority of Southern Sudanese. International observers considered the 2011 referendum on South Sudanese self-determination, in which 98 percent of voters chose to separate from Sudan, to be free and fair. President Kiir is a founding member of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) political party, the political wing of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Of the 27 ministries, only 21 had appointed ministers in charge, of which 19 are SPLM representatives. The bicameral legislature consists of 332 seats in the National Legislative Assembly (NLA), of which 296 were filled, and 50 seats in the Council of States. SPLM representatives controlled the vast majority of seats in the legislature. Through presidential decrees Kiir replaced eight of the 10 state governors elected since 2010. The constitution states that an election must be held within 60 days if an elected governor has been relieved by presidential decree. This has not happened. The legislature lacked independence, and the ruling party dominated it. Civilian authorities failed at times to maintain effective control over the security forces. In 2013 armed conflict between government and opposition forces began after violence erupted within the Presidential Guard Force (PG) of the SPLA, also known as the Tiger Division. -

C the Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan

C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following persons (from State Ministries of Livestock and Fishery Industries and FAO South Sudan Office) for collecting field data from the sample counties in nine of the ten States of South Sudan: Angelo Kom Agoth; Makuak Chol; Andrea Adup Algoc; Isaac Malak Mading; Tongu James Mark; Sebit Taroyalla Moris; Isaac Odiho; James Chatt Moa; Samuel Ajiing Uguak; Samuel Dook; Rogina Acwil; Raja Awad; Simon Mayar; Deu Lueth Ader; Mayok Dau Wal and John Memur. The authors also extend their special thanks to Erminio Sacco, Chief Technical Advisor and Dr Abdal Monium Osman, Senior Programme Officer, at FAO South Sudan for initiating this study and providing the necessary support during the preparatory and field deployment phases. DISCLAIMER FAO South Sudan mobilized a team of independent consultants to conduct this study. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. COMPOSITION OF STUDY TEAM Yacob Aklilu Gebreyes (Team Leader) Gezu Bekele Lemma Luka Biong Deng Shaif Abdullahi i C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...I ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... VI NOTES ..................................................................................................................................................................